NEWS RELEASES from the United States Department of Defense

No. 338-06 IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Apr 21, 2006

Airmen Missing In Action From WWII are Identified

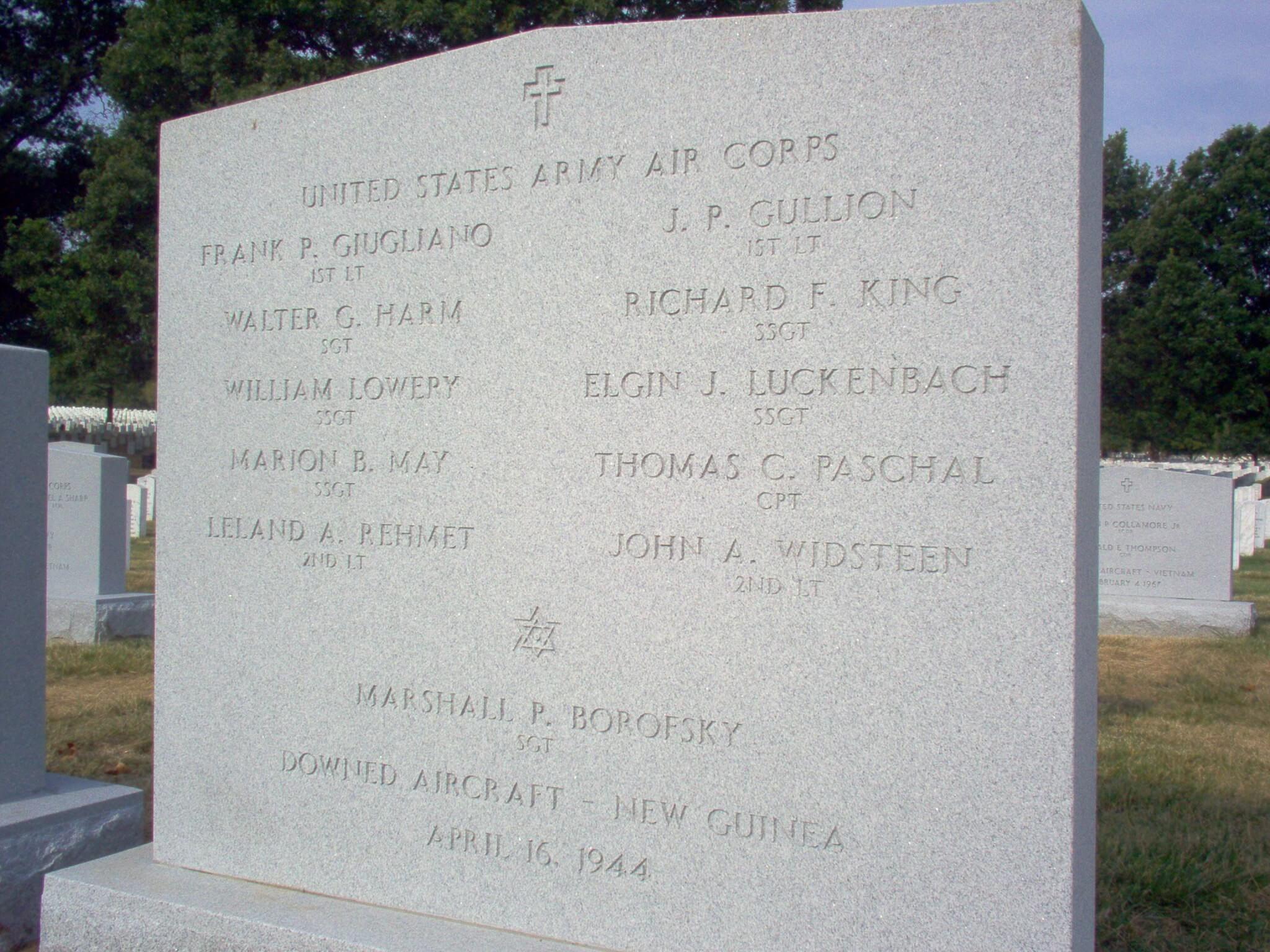

The Department of Defense POW/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) announced today that the remains of eleven U.S. airmen, missing in action from World War II, have been identified and are being returned to their families for burial with full military honors.

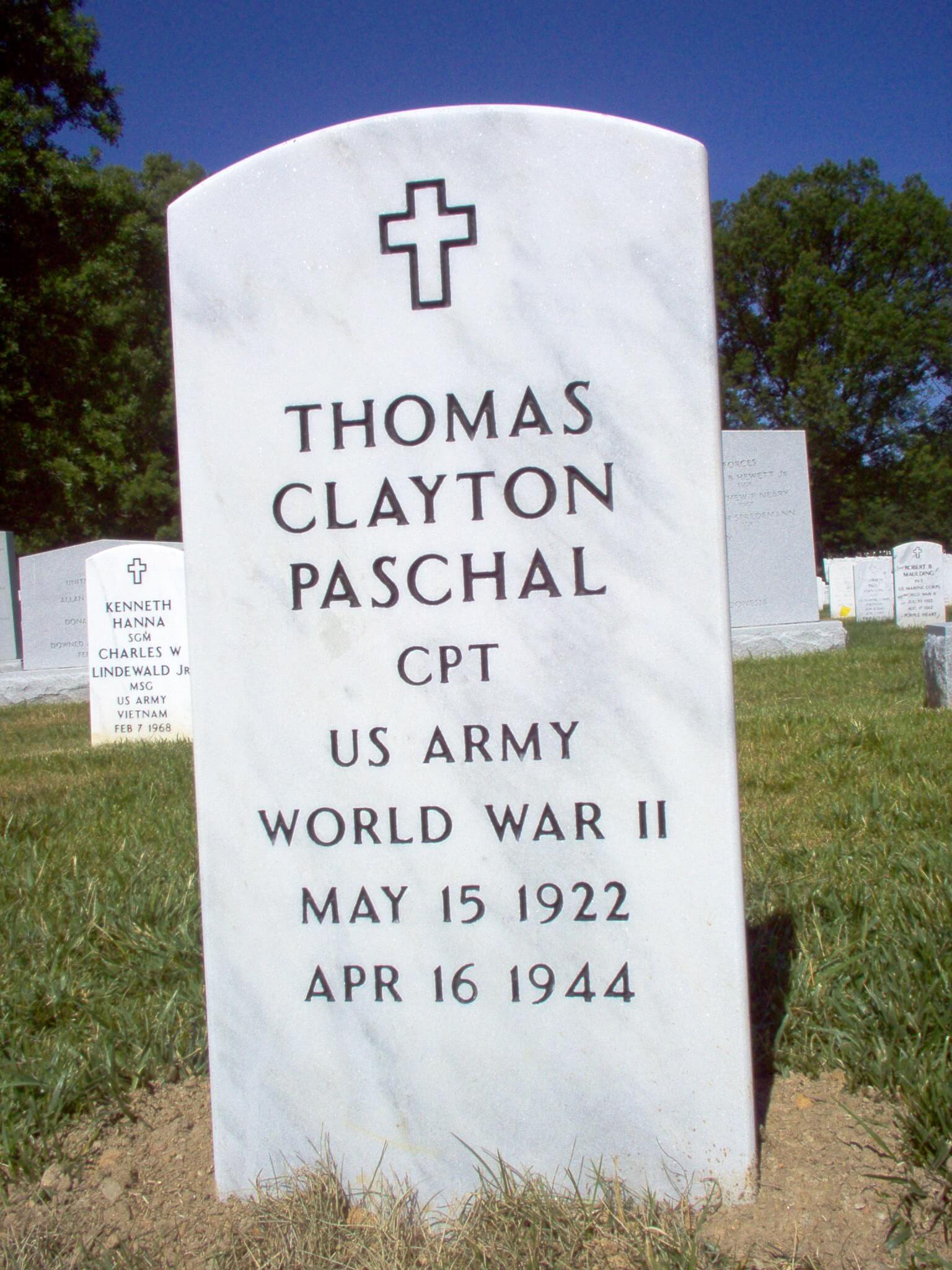

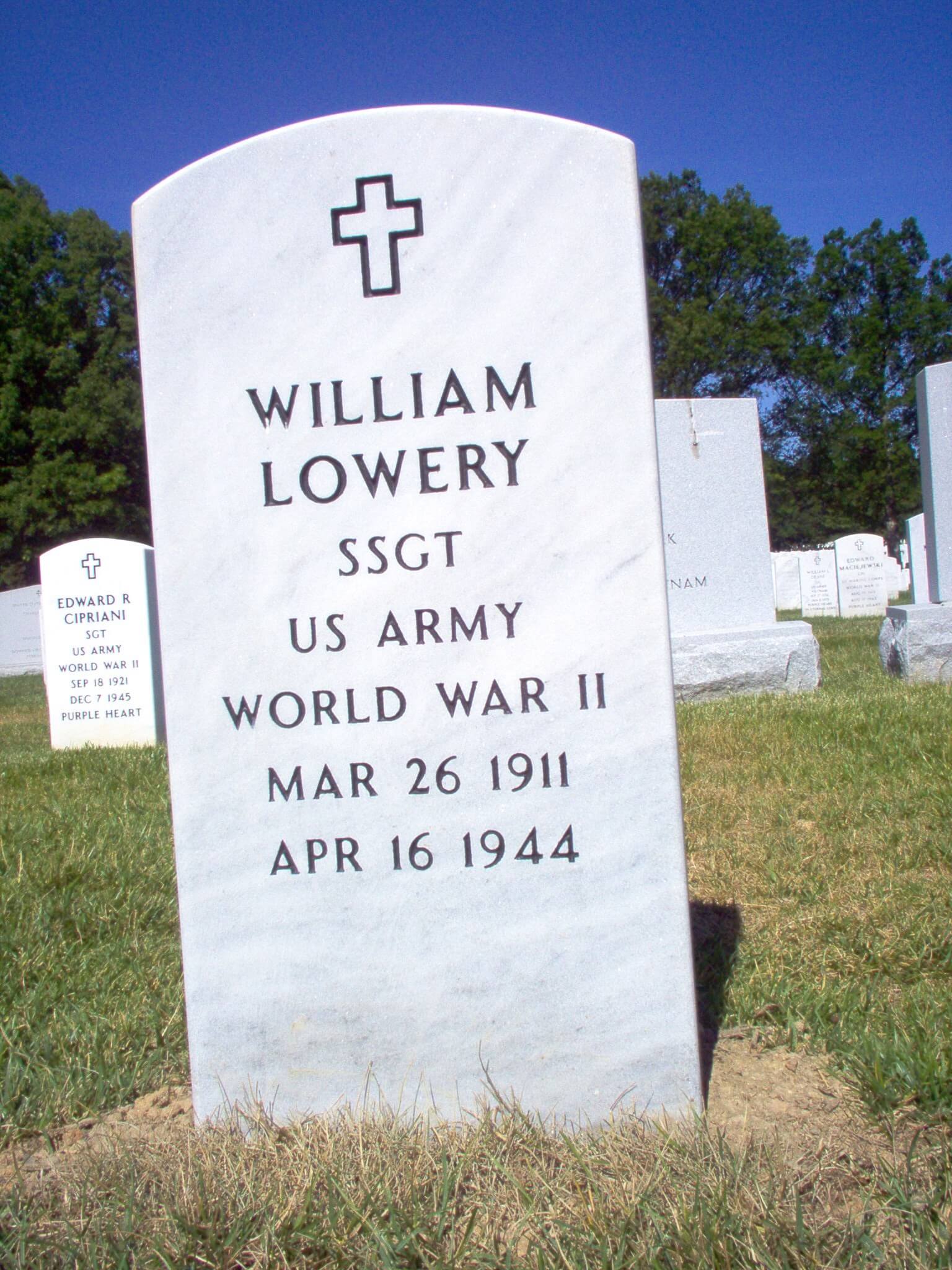

They are Captain Thomas C. Paschal, El Monte, California; First Lieutenant Frank P. Giugliano, New York, New York; First Lieutenant James P. Gullion, Paris, Texas; Second Lieutenant Leland A. Rehmet, San Antonio, Texas; Second Lieutenant John A. Widsteen, Palo Alto, California, Staff Sergeant Richard F. King, Moultrie, Georgia; Staff Sergeant William Lowery, Republic, Pennsylvania; Staff Sergeant Elgin J. Luckenbach, Luckenbach, Texas.; Staff Sergeant Marion B. May, Amarillo, Texas.; Sergeant Marshall P. Borofsky, Chicago, Illinois; Sergeant Walter G. Harm, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; all U.S. Army Air Forces.

The group remains of the entire crew are to be buried today at Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, DC, as are the individual remains of each man with the exception of King, Giugliano and Widsteen, whose families have elected hometown burials.

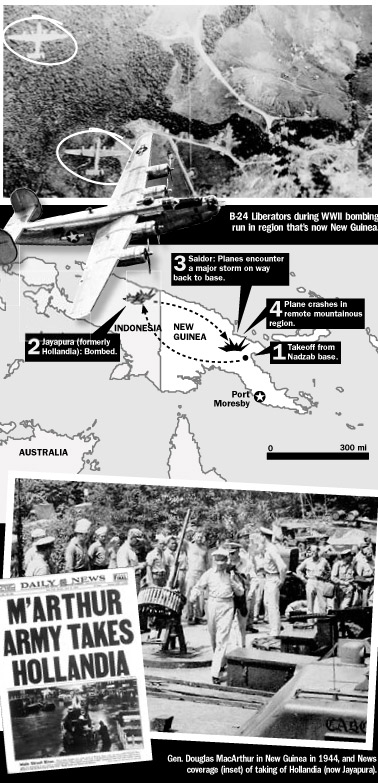

On April 16, 1944, Paschal and Widsteen were piloting a B-24J Liberator with the other nine men aboard. The aircraft was returning to Nadzab, New Guinea after bombing enemy targets near Hollandia. The plane was last seen off the coast of the island flying into poor weather.

The loss was investigated following the war and a military board concluded that the aircraft had been lost over water and was unrecoverable.

In early 2001 a team of specialists from the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) interviewed a native of Papua New Guinea who claimed to have found the aircraft crash and recovered identification media for May and Harm. The team surveyed the site in 2002 and found wreckage that matched Paschal’s aircraft tail number along with human remains. They also took custody of remains previously collected by the villager.

Later that year, two additional JPAC teams excavated the crash site and recovered additional human remains and crew-related artifacts. Identification tags were found for Luckenbach, May and Paschal. Other crew-related materials found were consistent with items used by the Army Air Forces around 1944.

Mitochondrial DNA obtained from dental and bone samples was one of the forensic tools used by JPAC scientists and Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory specialists to identify the airmen.

Eleven U.S. airmen, including four Texans, killed in the World War II crash of a B-24J Liberator bomber 62 years ago in the South Pacific will be honored in burials at Arlington National Cemetery on Friday, 22 April 2006.

The Pentagon’s Defense POW/Missing Personnel Office announced Thursday that the remains of all 11 men had been positively identified and were being returned to their families for burial with full military honors.

Eight of the men will be buried individually at Arlington with positively identified remains; the families of the other three chose hometown burials. In addition to those individual burials, there will be a burial at Arlington on Friday of “group remains” _ bone fragments associated with the crew that could not be positively identified with any of the 11 individuals.

The pilots of the B-24J were Captain Thomas C. Paschal of El Monte, California, and Second Lieutenant John A. Widsteen, of Palo Alto, California.

The other nine were:

First Lieutenant Frank P. Giugliano, of New York, New York; First Lieutenant James P. Gullion, of Paris, Texas; Second Lieutenant Leland A. Rehmet, of San Antonio, Texas; Staff Sergeant Richard F. King, of Moultrie, Georiga; Staff Sergeant William Lowery, of Republic, Pennsylvania; Staff Sergeant Elgin J. Luckenbach, of Luckenbach, Texas; Staff Sergeant Marion B. May, of Amarillo, Texas; Sergeant Marshall P. Borofsky, of Chicago, and Sergeant Walker G. Harm, of Philadelphia.

All were members of the U.S. Army Air Forces.

The bomber was returning to Nadzab, New Guinea, on April 16, 1944 after bombing enemy targets near Hollandia when it crashed. It was last seen off the coast of New Guinea flying into poor weather, the Pentagon said.

Remains were recovered in 2002 by a team of specialists from the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command, acting on information provided by a native of Papua New Guinea who reported finding the aircraft crash site.

Thomas C. Paschal

- Captain, U.S. Army Air Forces

- Service # 0-888688

- 408th Bomber Squadron, 22nd Bomber Group, Heavy

- Entered the Service from: California

- Died: 25-Feb-46

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

- Manila, Philippines

- Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Remains of ‘Black Sunday’ airmen returning home for burial

On April 16, 1944, Captain Thomas Paschal and his B-24J crew vanished in the clouds.

Paschal’s Liberator and more than 300 other planes were returning from a bombing run over Dutch New Guinea during World War II when they ran into what one pilot called the “worst storm I ever saw.”

The bad weather gave the American planes a tougher fight than they had gotten from the Japanese, claiming 54 crew members and 37 aircraft, including Paschal’s plane.

It was the Army Air Forces’ greatest non-combat aviation loss in World War II. Thirty fighter and bomber crew members are still missing.

But almost exactly 62 years after the day known as “Black Sunday,” the remains of Paschal and 10 fellow crew members will come home for a long-overdue burial. Their families will attend a funeral service on April 21 at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

“It’s just an emotional closure because all these years we really didn’t know what happened at the end,” said June Robertson of West Jordan, Utah. Her older brother, Second Lieutenant John Widsteen, was Paschal’s co-pilot. “It’s a feeling, he’s coming home.”

The 1944 storm didn’t happen without warning. A weather unit commander knew a severe front was forming and had argued for canceling the mission. But he was overruled, author Michael John Claringbould wrote in “Black Sunday,” a book about the disaster.

Maps were wrong

Along with the bad weather, the pilots had to deal with inaccurate maps that underestimated the heights of surrounding mountains.

Fifth Air Force planes already had pounded Japanese airfields and supplies seven times in Hollandia — now Jayapura in western New Guinea. Military leaders viewed that Sunday’s mission as a chance to further soften the area for an upcoming land invasion, Claringbould wrote. The Japanese offered only light resistance, and no U.S. planes were lost that day to enemy gunfire.

Paschal’s plane, which Claringbould said was called “Royal Flush,” remained in formation on the return flight with five other Red Raider 408th squadron Liberators until the storm hit near Saidor, records show. Paschal had been promoted to captain just eight days earlier.

“We passed through an exceptionally dark cloud formation, and when we emerged, Capt. Paschal … was no longer in our formation,” 1st Lt. Dwain E. Harry wrote in an April 20, 1944, statement.

For decades, one crew member’s cousin, Saverio Giugliano wrote letters to people inside and outside the military, hoping someone had found the plane. As a young soldier, he had invaded Hollandia with the 24th Division six days after First Lieutenant Frank P. Giugliano’s fatal flight.

Saverio Giugliano has clear memories of the hot, humid island, and he didn’t want to think that his cousin — the smiling bombardier in a black and white photo, the “kibitzer” who teased the girl cousins at family gatherings — would remain in that jungle forever.

“I felt that if they found him, at least he would be buried by his mom and dad,” said Giugliano, of Berwick, Pennsylvania.

Hunter found wreckage

About four years ago, a villager hunting wallaby high up in the Finisterre Mountains of Papua New Guinea reported finding the rusting hulks of two B-24s in the Lae region near Kunukio.

“The people (where the planes were found) are afraid of ghosts,” said Gwen Haugen, the civilian forensic anthropologist who led the 2002 recovery effort. “Nothing had been touched. It was almost as it had come to lay, and how time and gravity had moved it.”

Using a helicopter, rappel lines and scaffolding, a military recovery team spent several months in austere conditions excavating the crash site. They found the cockpit caught in the trees, a piece of nose art that seemed to depict playing cards, and human remains near where the airmen would have been sitting on the aircraft.

Near the bomb racks, they found Giugliano’s remains in a shredded bomber jacket. His broken sunglasses were still inside a case tucked into his pocket. Haugen saw his dog tag and thought, “Frank Giugliano, you’re going home.”

Saverio Giugliano heard the news and “cried like a baby.” He called Frank’s other cousin, Joe Cassese, in Ozone Park, Queens, New York.

“I got little goose pimples,” said Cassese, 84, a former Marine who saw Frank Giugliano in Hawaii just before he died. “We all want him back.”

James Paschal, Thomas Paschal’s brother, said his family was told the Royal Flush had gone down in the ocean, an explanation most of them accepted.

Father awaited son’s return

“My father, for as long as he lived, was expecting my brother to walk back into the door at any time,” said James, 76, of Topeka, Kansas.

Tom Paschal rose through the enlisted ranks before the Army taught him to fly. He was engaged to his high school sweetheart. He had dark, Cherokee good looks. And he was “the boss” as far as his three younger siblings were concerned, James Paschal recalled.

“He was always my hero,” Paschal said. “He just lived up to it.”

At least two of the men who flew on the Royal Flush will be buried in their families’ hometowns, according to their families’ wishes. The rest will be buried at Arlington. Soldiers will escort the crew’s caskets from the military’s Central Identification Lab in Hawaii to their place of burial.

For Paschal, it wasn’t a tough decision to bury his brother in Arlington.

“I’m sure, knowing my brother, he’d want to be with his men,” he said. “If I died with my crew, I think I’d like to stay with them, and I’m sure that he would be the same way.”

Long wait ends for area family

WW II airman’s body found in New Guinea

What James Paschal remembers about growing up in El Monte during the 1940s is waiting for his brother, Captain Thomas Paschal, to return from World War II after he went missing.

On Friday, almost 62 years after Paschal’s plane vanished during a storm, his remains and those of 10 fellow crew members were buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia with full military honors, according to the Department of Defense.

“It had been more than 60 years since it happened, my goodness,” James Paschal, 76, said Tuesday. “It’s the way you think it would be when you get the kind of news, just unbelievable.”

James Paschal and his wife, Lee, attended the service at Arlington.

“Being at the funeral was amazing; it was like the wait was finally over,” James Paschal said.

Officials said Paschal’s remains were found in 2001 when a hunter found the aircraft wreckage of two B-24s in the mountains of Papua, New Guinea. A military recovery team spent months excavating the crash site and recovered a cockpit and human remains.

“They told us someone had last seen the plane going into the ocean,” James Paschal said. “We presumed they’d be picked up by the Navy and if not we thought he probably passed on and was at the bottom of the ocean.”

On April 16, 1944, Thomas Paschal was piloting a B-24J Liberator with 10 other men aboard, returning from bombing enemy targets during the “Black Sunday” mission to Hollandia, when they ran into bad weather, officials said.

According to the Department of Defense, the storm claimed the lives of 54 crew members and 37 aircraft.

It was considered the Army Air Forces’ greatest non-combat aviation loss in World War II, officials said.

Thirty fighter and bomber crew members are still missing.

Although Paschal was listed by the military as being a resident of El Monte, he never lived in the city.

However, James Paschal said his family and Tom’s fiance lived in El Monte when Tom disappeared and stayed there for about 10 years hoping one day he would return.

“This whole thing is unbelievable,” James Paschal said. “My father always knew Tom would come come home and walk through the door one day. It’s like he finally did.”

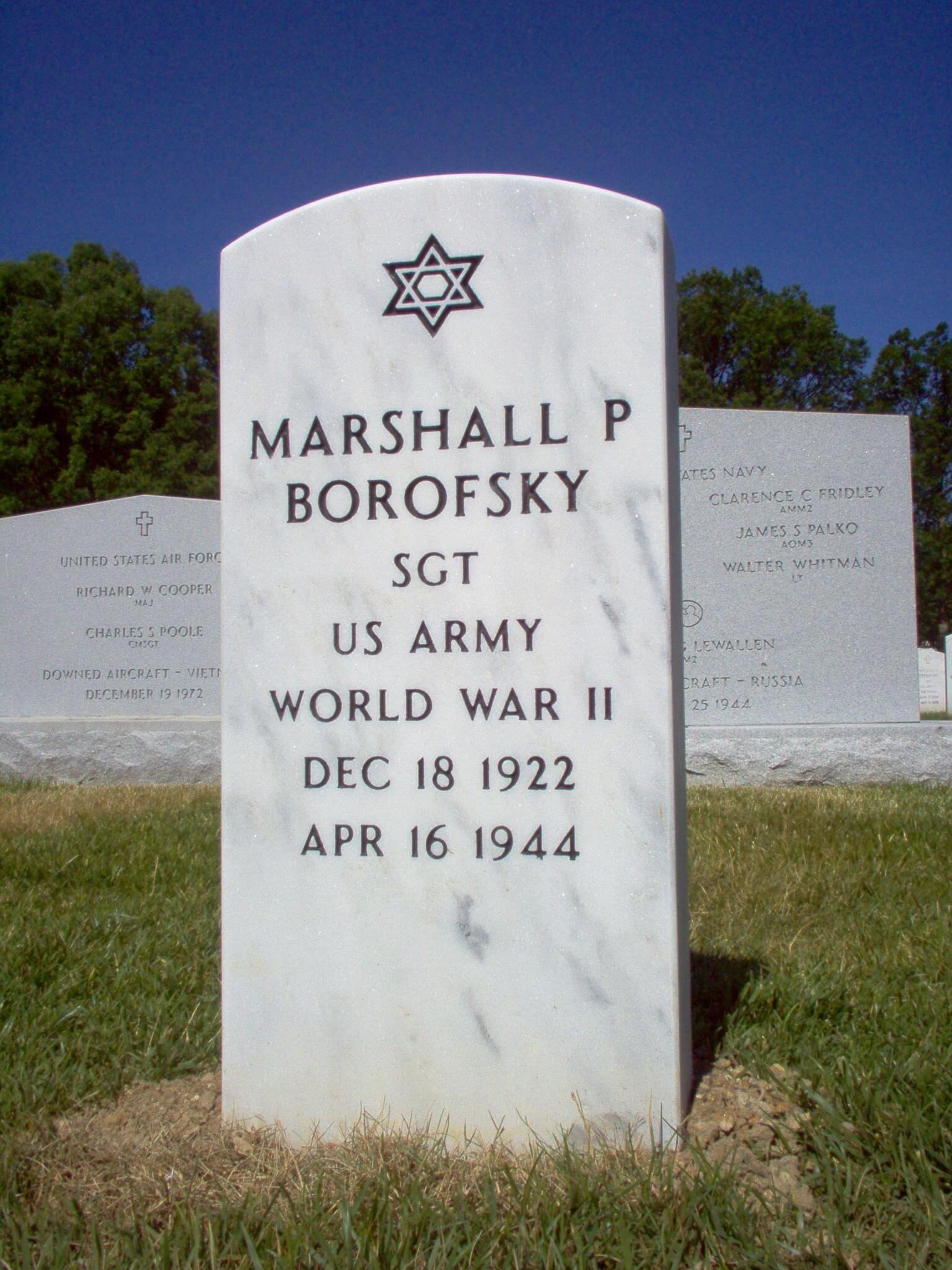

Marshall P. Borofsky

- Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Forces

- Service # 16172175

- 408th Bomber Squadron, 22nd Bomber Group, Heavy

- Entered the Service from: Illinois

- Died: 25-Apr-46

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

- Manila, Philippines

- Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Richard F. King

- Staff Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Forces

- Service # 34350910

- 408th Bomber Squadron, 22nd Bomber Group, Heavy

- Entered the Service from: Georgia

- Died: 25-Feb-46

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

- Manila, Philippines

- Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Moultrie veteran is buried 60 years later

MOULTRIE – Staff Sergeant Richard Fowler King’s bombing mission to Indonesia was successful. But he never came back from the World War II mission.

King’s B-24J Liberator ran into a tropical storm off the coast of New Guinea and the plane never returned from its April 16, 1944, bombing run.

For more than 60 years, it seemed there was little chance of recovering the remains of King and the other 10 crewmen.

Saturday, more than 62 years after the fateful mission, King was laid to rest with full military rites.

Another ceremony will be held Friday in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, where all personal items not positively identified and the unidentified remains of crewmen from the crash site will be buried together. All 11 names of the crew will be placed on the grave’s tombstone with a description of the plane and mission.

Two years after King’s plane went missing, the Air Force changed his status from “Missing in Action” to “Presumed Dead” after a review board concluded that it was likely the plane was lost over water and the remains of the crewmen were unrecoverable.

But in 2001, a hunter reported finding a U.S. aircraft in a forest near Saider, New Guinea. King and the other crew members were positively identified after officials searched the areas for nearly two years.

Inez Jenkins, who was married to King at the time of his disappearance, said she was notified in 2001 that the plane had been found and all crew members had lost their lives. King was identified using a DNA sample from his sister, Ellen Raiford of Jacksonville, Florida.

“It was something that we have wanted to know definitively,” she said. “We did not know for sure until 2001.”

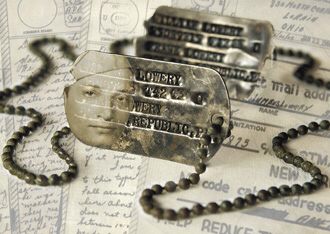

The research crew found personal items in the wreckage that included rings, dog tags and fragments of shoes, gloves and leather jackets.

They found Jenkins’ high school class ring, which she ordered in King’s size and exchanged with his class ring, which had been ordered in her size, as a sign of their friendship through grade school.

“Ours was a friendship that grew into love and marriage,” she said

April 15, 2006:

World War II airman finally returns home

Inez Jenkins clutched a black-and-white framed photo Saturday afternoon.

Sixty-two years after Jenkins lost her husband, Staff Sergeant Richard Fowler King, on a mission in World War II, she said a final farewell while friends and family honored him with a military ceremony at Westview Cemetery in Moultrie.

“I’ve had an empty grave for 62 years,” Jenkins said. “Now I have solace.”

The photograph, taken 63 years ago, captured a moment between husband and wife.

Jenkins, then Inez King, and her husband, called “Fowler” by friends, were in Greenville, South Carolina, for his last phase of Army Air Forces training before heading overseas to serve in the South West Pacific Theatre of World War II.

On April 16, 1944, King, a radio operator on a B-24J Liberator out of Nadzab, New Guinea, was headed home after completing a mission to bomb Hollandia — now Jayapura — in Indonesia. A tropical storm hit the area, and King’s aircraft was last seen over the coast of New Guinea. Eleven men died in the crash, and 30 planes went missing. Military forces spent weeks looking for remains but found no trace of wreckage. King’s family assumed his plane went into the ocean. He was 26 years old.

In 2001, a villager in a remote area of Papua, New Guinea stumbled across artifacts. The items were given to authorities, and the United States was notified. Through efforts of the forensic lab at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii, King and his fellow crew were identified using DNA technology. A team of archeologists spent nearly two years sifting through the wreckage.

That year King’s sister, Ellen Raiford, received a startling phone call. It was a military representative asking for a DNA sample.

“We always thought he went down in the Pacific,” Raiford said. “I’d always wonder if the plane went into the ocean … I’d have dreams about him swimming in the ocean and wondered if sharks got him.”

Jenkins couldn’t sleep when she heard the news. Among items found was a gold ring described as a woman’s-style ring in a larger size.

She and King were high school sweethearts. They were friends in grade school, became affectionate in high school and eventually got married. While in high school, each ordered their class ring in the other’s size. King was wearing Jenkins’ ring when his plane went down.

“Every day I’d wonder what life may have been like if he had come home, and every day I’d wonder where he really was,” Jenkins said.

Raiford was 16 years old when her older brother was drafted into the war. He was the family’s only son, which was a major concern for King’s parents as they sent him off to war.

“He knew he had to go; there was no exception,” Raiford said.

Raiford described her brother as an energetic, loving man. He worked for a gas company in Moultrie, and Raiford said he found the work rewarding.

“He’d help people in the county get refrigeration and washing machines,” she said.

Jenkins said King was a Christian, very trustworthy and dedicated to work.

“The way I saw him every day, I remember him that way … he had a nice smile when he left each morning,” Jenkins said.

Raiford’s brother-in-law, Logan Thackrey of Valdosta, said the military has been overwhelmingly supportive in helping the family honor King.

Jenkins said it was good to see King get the honor he deserved.

“He was called to perform a duty for our country and fulfilled it. He gave his life for me, for you, and when he did that, he made life better for everyone today,” she said.

Later this week, Raiford, Jenkins, Thackrey and family will head to Washington, D.C., to take place in a formal military burial ceremony with families of the other crew members at Arlington National Cemetery.

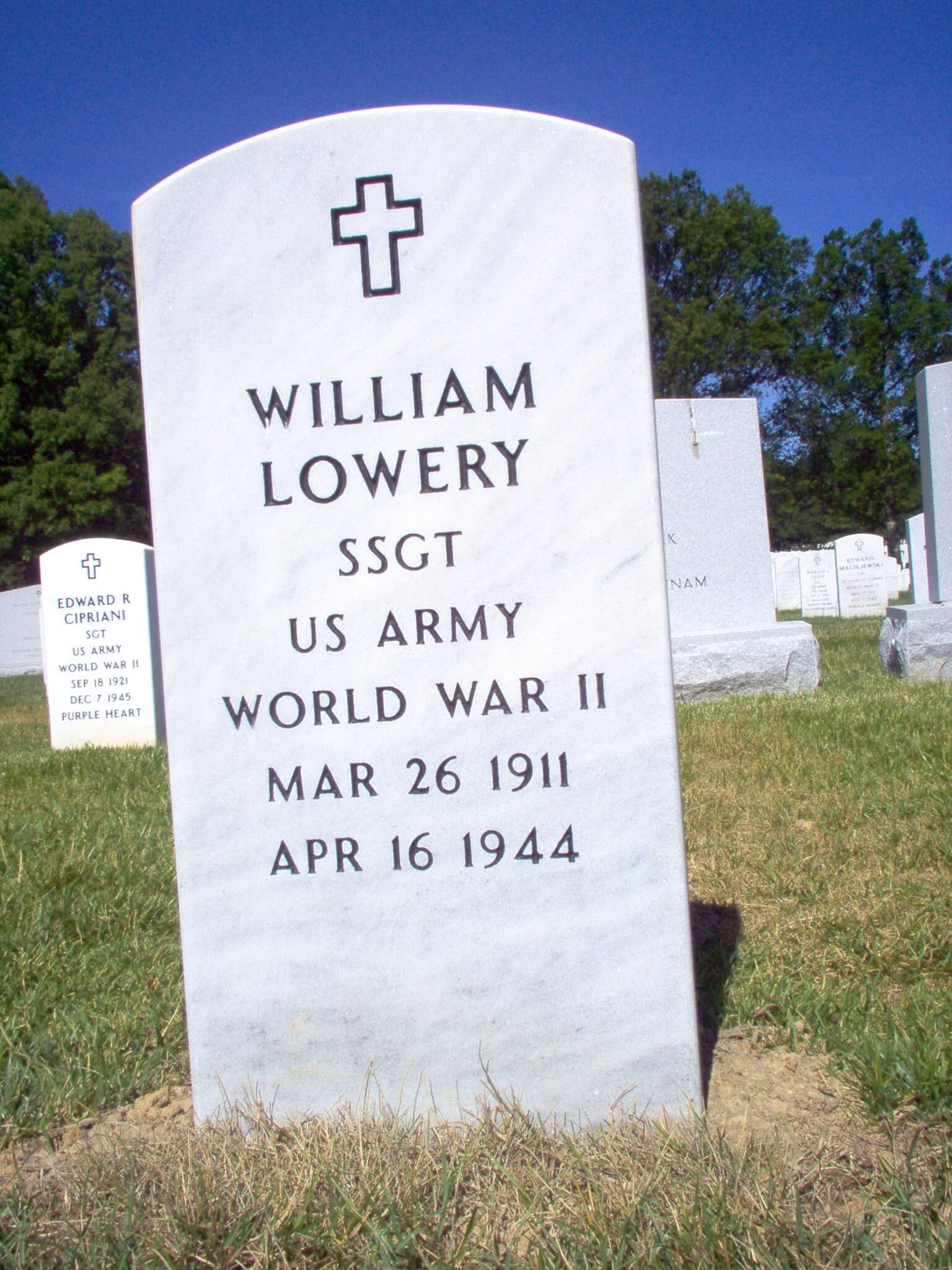

William Lowery

- Staff Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Forces

- Service # 15089215

- 408th Bomber Squadron, 22nd Bomber Group, Heavy

- Entered the Service from: Pennsylvania

- Died: 25-Feb-46

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

- Manila, Philippines

- Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

For family, the uncertainty was the hardest part.

One of seven siblings raised in the Fayette County mining town of Republic, northwest of Uniontown, Mr. Lowery went off to fight in World War II and never came home.

His family knew that his B-24 bomber had disappeared somewhere near the coast of what is now Papua New Guinea on April 16, 1944 — 62 years ago today — when he was 33. They knew that the plane’s wreckage and the bodies of its 11 crew members could not be located. And they knew that the Army had declared the men dead in February 1946.

But they could never be sure of exactly what had happened to Staff Sergeant William Lowery.

“I’d watch old war movies and I’d just sit there wondering what happened to my uncle,” said Jerome Lowery, 63, of Uniontown, whose father, Albert, was William’s younger brother. “We used to talk about him all the time.”

The villager had no idea that what he found would lead to the discovery of the remains of a United States Army bomber that had crashed in the area 57 years ago, killing the 11 World War II soldiers who were on board.

One of those soldiers was Staff Sergeant William Lowery of Republic, whom the Army declared MIA along with his 10 comrades in 1944.

Two years later, the Army presumed that the soldiers were dead and assumed that their plane, which they could not find, had crashed during a storm somewhere in the Pacific.

This left Lowery’s family with many unanswered questions, and his relatives who are finally getting closure say they are sorry that Lowery’s parents, brothers and sisters never did.

The ring that the hiker found was brought to the attention of the U.S. Embassy, which led to a 2002 search in the ravine where the bomber had crashed in Papua New Guinea, after a strike mission on Japanese targets near Hollandia.

A U.S. team of excavators and forensic archeologists from the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command, whose goal is to find and identify American remains from all wars, swept into the ravine and immediately started finding objects owned by the soldiers, such as rings and watches, all still intact. The discovery that solved the mystery of what had happened to the bomber was the tail of the plane with the serial number on it.

Dog tags and skeletal remains were also found, and the military was finally able to identify the soldiers who had been missing for so many years.

Lowery’s niece, Theresa Zagore, who lives near Chicago, was the first to get a call, and she cried when she found out that there was possible information about the uncle she had heard so much about growing up.

Zagore’s sister, Marie Alexander, also from the Chicago area, said she also cried when she heard the news. The sisters said they cried for their mother, who would have loved to be a part of what was taking place. They cried for their aunts and uncles who had already passed on and never got the closure they had longed for. But there was also joy in their tears because their uncle was finally coming home.

William Lowery never married or had children, but his nieces and nephews heard about the great man he was from their parents all of their lives.

Alexander said that to them, “Uncle Willie” was always alive, because their mother had never believed that he was dead.

“When we first heard that there was information about him, I hoped that he was still alive,” said Alexander. “We always believed that there was a chance he was alive. So it was disappointing in a way, but it was also good to finally know what happened.”

When Alexander was sure that the remains of her uncle had indeed been found, she shared the news with her cousins living in this area.

Norma Golembiewski of Brownsville said it was a “very emotional” time when she heard the news.

Since William Lowery had died before Zagore and Alexander were born, they knew him only through photographs and stories their mother told them about him.

They recalled being told that he was intelligent and loved to joke around.

But Golembiewski said that she experienced some of Lowery’s best qualities firsthand when she was a child.

“He was very personable and kind-hearted,” said Golembiewski. “He was a caring person and always took time to be with us.”

Golembiewski said she was “elated” to have closure on her uncle’s death after more than 60 years.

“It was a miracle that they finally found the plane,” said Golembiewski. “It was sad, but, at the same time, I felt good for my dad and I wished he was still living. We assumed the plane had gone down in the storm, but it was always a mystery where it went down.”

Since Lowery’s dog tags were recovered from the wreckage, Golembiewski said she was also glad that the family could have something that belonged to her uncle.

Jerome Lowery, nephew to William Lowery, said he was also happy to finally know what had become of his uncle.

“Ever since I was young I wondered what happened,” said Jerome Lowery of Uniontown, adding that he had shared stories of his uncle with his children and grandchildren. “The whole family always talked about it and wondered what happened to him.”

Jerome Lowery said that when he found out that his uncle’s remains had been identified after all these years, “You could have knocked me over with a feather.”

“It’s amazing what the U.S. military went through to identify the bones and what they are going to do to memorialize him,” said Jerome Lowery, referring to William Lowery’s upcoming burial at Arlington National Cemetery on Friday.

“I just can’t say enough,” said Jerome Lowery, adding that the majority of his family would be attending the memorial service. “We want to be there to thank him for what he did, giving his life for his country.”

Jerome Lowery said that although he was very small when his uncle left to fight in World War II, he can remember a young man in a military uniform holding him when he was a child, and he would visit as often as he could.

“When he left for active duty nobody in the family ever saw him again,” said Jerome Lowery. “It’s great that now he will be buried with dignity and honor, as he should be.”

Alexander commented that her mother had told them growing up that their uncle had been scheduled to return home, but instead he had courageously volunteered to go on the mission that ended his life.

Golembiewski said that while she may not be able to attend the ceremony because of an illness in her family, her uncle is in her “thoughts and prayers.”

“I know he is gone, but it seems as though part of him is still here now,” said Golembiewski.

Alexander agreed with that sentiment, commenting on how to her and her sister, their uncle has always been alive, if only in sprit.

“To us, he still is,” said Alexander.

Now, more than half a century after Mr. Lowery’s plane crashed into the jungles of Papua New Guinea, his family will be able to give him a proper burial.

The remains of Mr. Lowery and his crew, discovered in 2001 and identified over the past five years by a military agency dedicated to locating soldiers who did not return from America’s conflicts, will be laid to rest with full military honors Friday in Arlington National Cemetery.

And even though all of Mr. Lowery’s siblings are dead, this unexpected chapter of his story is sending yet another wave of emotion over his surviving relatives.

“I was totally floored,” Jerome Lowery said, recalling his reaction when he learned that his uncle had been found. “I just couldn’t believe it. The whole thing is phenomenal.”

For the nieces, nephews and other extended family members who will gather in Arlington to celebrate Mr. Lowery’s life, Uncle Willie is a man they know mostly through family stories and photographs.

“He was very easygoing, and he got along with everybody,” said Marie P. Alexander, who never met her uncle but learned about his life from her mother, Florence Phillips, William’s older sister.

“My mom always talked about him being very smart,” said Ms. Alexander, who grew up in Republic and now lives in Streamwood, Ill. “I also know he liked to joke a lot. That’s how his name would come up. Something funny would happen, and someone would say, ‘I wish Willie was here.’ ”

Born in 1911, Mr. Lowery was the fourth child of Frank and Angelina Lowery, Italian immigrants who settled in Republic, where Frank worked in the coal mines and built the family home in 1929.

The shortest student in his class at the beginning of his sophomore year of high school, Mr. Lowery shot through a growth spurt and finished the year taller than all of his classmates. That period of physical growth soon paralleled his increasing personal and family responsibilities.

Mr. Lowery’s mother was bedridden for much of her life and died in 1941. As her illness worsened, Ms. Alexander said, Mr. Lowery stepped up to help.

“He felt responsible for the well-being of the family, keeping the family together and running smoothly,” Ms. Alexander said. “As my grandfather got older, he became more of a father figure.”

Mr. Lowery, who never married, hit the road at the height of the Depression, traveling across the country looking for jobs and sending short notes home to assure his family that he was OK. By January 1942, he had enlisted in the Army.

A little more than two years later, he was serving as a gunner on a B-24 bomber, flying with more than 200 aircraft April 16, 1944, a day that came to be known as “Black Sunday,” in a massive bombing campaign against a Japanese air base in what was then Hollandia, Dutch New Guinea.

After destroying the Japanese base, the U.S. forces began the return flight to Nadzab, New Guinea, only to encounter severe weather that eventually brought down 30 planes, including Mr. Lowery’s.

Airborne searches failed to turn up any trace of Mr. Lowery’s bomber, and the military declared the plane’s crew missing and then dead, concluding that the plane had crashed into the sea based on its last known location.

The Lowery family took the news hard.

“That was very traumatic,” said Florence M. Gilchrist, 74, of North Huntingdon, who was 10 when her Uncle Willie left for war. “I can remember my father being very upset, even though he wasn’t that type of person.”

Mr. Lowery’s brothers and sisters struggled to balance the hope that he still was alive with the likelihood that he had been killed, Mrs. Gilchrist said.

“For a while, there was hope that he would be found. But after a while, they realized that it wasn’t meant to be.”

Still, Mr. Lowery’s sister Florence and brother Columbus refused to believe that their brother was dead, Ms. Alexander said.

“They said that his plane went down somewhere and that he had amnesia,” Ms. Alexander said. “That was their theory. It was easier for them to understand.”

Deep in the jungle, the crash site was overgrown by vegetation and remained unreported until March 2001, when hikers discovered two sets of dog tags and alerted the U.S. Embassy in Papua New Guinea.

The information was passed on to the Army’s Central Identification Laboratory, a branch of the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command, which tracks down missing U.S. military personnel, and a team was dispatched to excavate the crash site.

Theresa A. Zagore, one of his nieces and Ms. Alexander’s sister, received a call on her cell phone while driving from work to her home in Hoffman Estates, Ill. The caller asked if she was related to William Lowery.

“Honestly, I was speechless for about four seconds,” said Mrs. Zagore, who pulled over to the side of the road because she was so shaken. “It took me a while to comprehend what she was asking. I could feel the goosebumps.”

The dog tags of six crew members, including Lowery, had been found, along with human remains, parts of watches, belt buckles, coins, lighters and the plane’s tail section, where the aircraft’s painted identification number was still visible. DNA testing confirmed that Mr. Lowery and his crew had been located.

The ceremony in Arlington, in which all 11 crew members will be buried in separate caskets next to a 12th casket holding unidentified remains, is bound to be bittersweet.

Mr. Lowery’s siblings and father died without knowing where their lost brother and son was, and whether he ever would come home.

“I think they would’ve all been happy,” Mrs. Gilchrist said. “You can’t change the fact that he was killed, but now he has his own place. I think my dad would have been really happy about that.”

But both Ms. Alexander and Mrs. Zagore, who were initially upset that their mother, Florence, had died before her brother was discovered, have since come to believe that the timing of the discovery was for the best.

“At first, I said, ‘God, I wish Mom was here,’ ” Ms. Alexander said. “But then I said, ‘Could she have handled this?’ I think, in God’s infinite wisdom, it’s a blessing that he took her first. Now they’re together, the brother and sister who were so close in life.”

Frank P. Giugliano

- First Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Forces

- Service # 0-673063

- 408th Bomber Squadron, 22nd Bomber Group, Heavy

- Entered the Service from: New York

- Died: 25-Feb-46

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

- Manila, Philippines

- Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Airmen laid to rest 60 yrs. later

WWII bombing crew lost in Pacific storm finally honored in Arlington rites

BY ADAMS NICHOLS

COURTESY OF THE NY DAILY NEWS

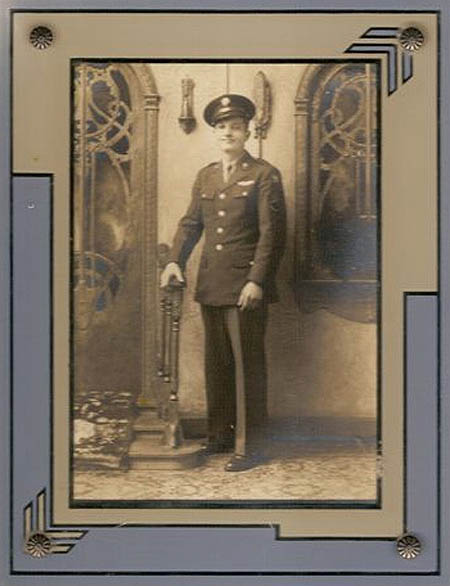

WWII bombardier Frank Giugliano, who was killed when his aircraft crashed in jungle in 1944. Wreckage was found four years ago, and eight crewmen were finally buried yesterday.

For nearly 60 years, 1st Lt. Frank Giugliano’s remains lay in the shattered shell of a World War II bomber, lost deep in a sweltering South Pacific jungle.

The wreckage was seen only by local villagers too terrified of evil spirits to go near, so the New York bombardier and his crew members remained missing in action, presumed dead.

But the doomed bomber’s crew of 11 men was never forgotten by Giugliano’s family. And yesterday, they brought them home.

The Army Air Force man’s cousins Saverio Giugliano, now 82, and Joe Cassese, 84, were at Arlington National Cemetery yesterday for the goodbye they had waited their lives to say.

“We grew up together, we were close,” said Saverio, who refused to give up hope his cousin, who died aged 24, would be found.

“It was good to see this happen. It’s good to know we brought him home.”

Yesterday, eight of the crew members were laid to rest at individual funeral services in the national cemetery for war heroes.

A group burial of bone fragments that could not be positively identified also was carried out with full military honors – watched by Frank Giugliano’s relatives.

Next month, another funeral for the bombardier’s identified remains will lay him next to his mother, Ethel, and father, Michael, in St John’s Cemetery in Queens.

“They would have liked that,” Saverio said. “Losing Frank was tough on them, particularly his mother. She never accepted he’d gone.”

Frank Giugliano, from Ozone Park, Queens, died in the April 16, 1944, bombing mission that resulted in the biggest noncombat aviation loss of the war.

As it returned with more than 300 other planes from successfully pounding Japanese airfields in Hollandia – now Jayapura in Indonesia – the bomber, dubbed Royal Flush, ran into a ferocious storm.

Flying in formation with five other Red Raider 408th Squadron Liberators and armed with maps that inaccurately judged the height of surrounding mountains, the Royal Flush entered dark clouds – and disappeared.

“We passed through an exceptionally dark cloud formation and, when we emerged, \[the Royal Flush\] was no longer in our formation,” First Lieutenant Dwain Harry wrote in a 1944 statement.

The plane had been making its way back to base at Nadzab, New Guinea, when it hit the storm near Saidor.

Along with the Royal Flush, 37 aircraft were crippled by the storm, and 54 crew members lost their lives. Thirty are still listed as missing.

Investigators believed the Royal Flush had gone down in the sea until a villager hunting wallaby in the rugged Finisterre Mountains stumbled upon the wreckage four years ago. He reported it to authorities, who informed the U.S. military.

“Nothing had been touched,” Gwen Haugen, an anthropologist who led the recovery effort, told author Michael Claringbould, who wrote about the tragedy in a book titled “Black Sunday.”

The jungle was so impenetrable a military recovery team had to spend months searching the crash site, rappelling in from a helicopter and a specially built scaffold.

They found the cockpit caught in trees, a playing cards logo painted on its nose still visible. Human remains were where the airmen would have been seated.

Close to the bomb racks, Frank Giugliano’s remains were found, still clad in a bomber jacket, his smashed sunglasses in a case in his pocket.

The young man, who went to school at Queens’ Public School 63 and worked as a printer before enlisting, still had his dog tags around his neck.

Haugen said she read them and said, “Frank Giugliano, you’re going home.”

“You’ve got to give the government a lot of credit,” Saverio said. “They never gave up on him.”

James P. Gullion

- First Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Forces

- Service # 0-803142

- 408th Bomber Squadron, 22nd Bomber Group, Heavy

- Entered the Service from: Texas

- Died: 25-Feb-46

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

- Manila, Philippines

- Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

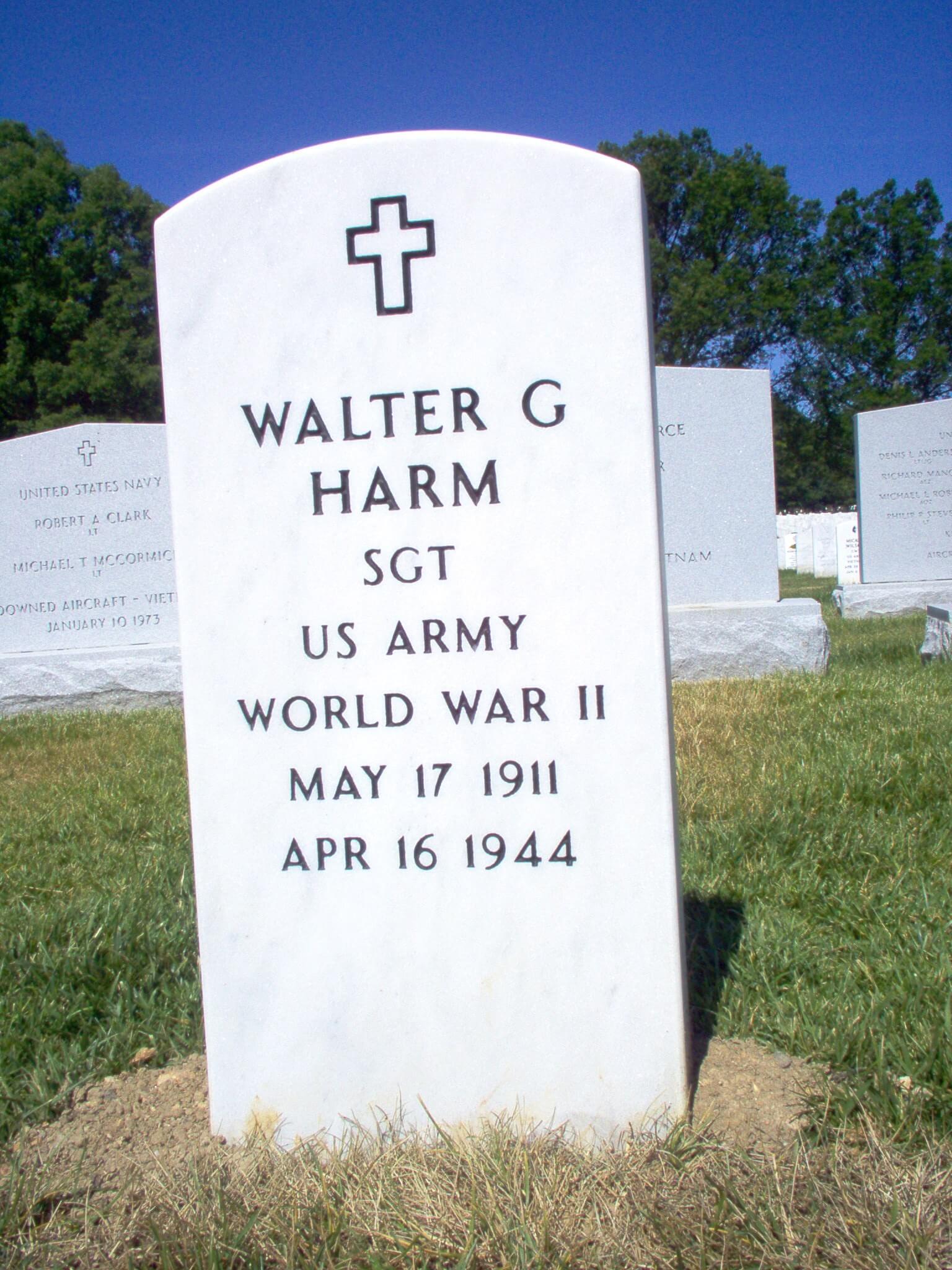

Walter G. Harm

- Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Forces

- Service # 33184186

- 408th Bomber Squadron, 22nd Bomber Group, Heavy

- Entered the Service from: Pennsylvania

- Died: 25-Feb-46

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

- Manila, Philippines

- Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

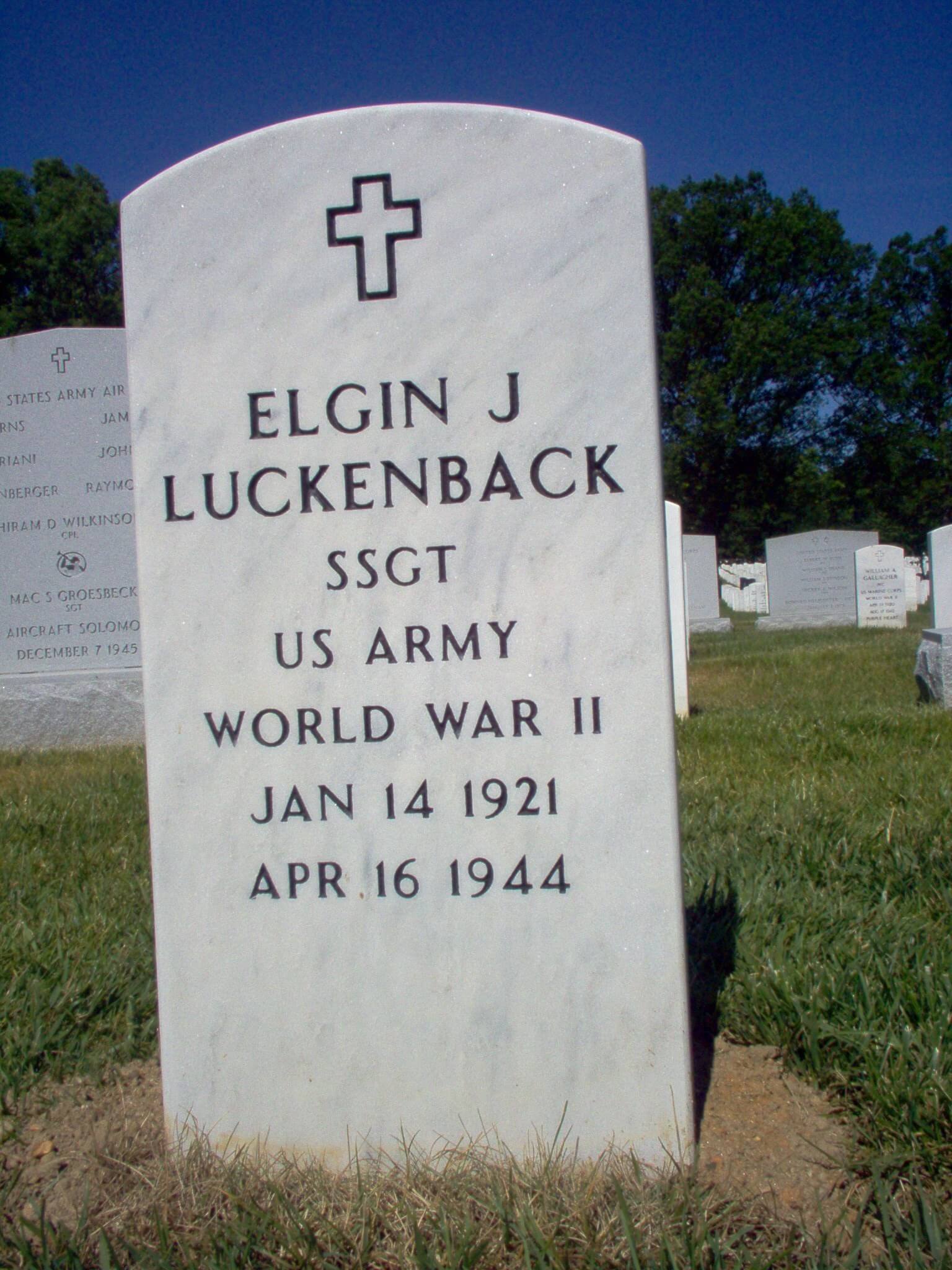

Elgin J. Luckenbach

- Staff Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Forces

- Service # 18106009

- 408th Bomber Squadron, 22nd Bomber Group, Heavy

- Entered the Service from: Texas

- Died: 25-Feb-46

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

- Manila, Philippines

- Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Marion B. May

- Staff Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Forces

- Service # 38108748

- 408th Bomber Squadron, 22nd Bomber Group, Heavy

- Entered the Service from: Texas

- Died: 25-Feb-46

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

- Manila, Philippines

- Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Leland A. Rehmet

- Second Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Forces

- Service # 0-752627

- 408th Bomber Squadron, 22nd Bomber Group, Heavy

- Entered the Service from: Texas

- Died: 25-Feb-46

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

- Manila, Philippines

- Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

John A. Widsteen

- Second Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Forces

- Service # 0-691166

- 408th Bomber Squadron, 22nd Bomber Group, Heavy

- Entered the Service from: California

- Died: 25-Feb-46

- Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

- Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

- Manila, Philippines

- Awards: Purple Heart

24 June 2006:

WWII Airman’s Remains Come Home To Palo Alto

A Northern California family’s decades-old war story acquired an emotional epilogue on Friday when partial remains of an Army pilot who disappeared in the South Pacific more than six decades ago were buried with military honors.

Second Llieutenant John Austin Widsteen was 22 years old on April 16, 1944, when he and 10 fellow airmen aboard the Royal Flush failed to return to their Papua New Guinea base from a bombing mission in what is now Indonesia.

Widsteen’s baby sister, now 77, was his closest surviving relative at the funeral, which also drew a pair of gray-haired cousins and several nieces and nephews.

“He is still that 22-year-old,” said Widsteen’s sister, June Robertson. “I can’t imagine him as an old man.”

Since 1946, when the Army declared the crew of the B-24 Liberator bomber dead, the official explanation was that the Royal Flush probably crashed into the sea during a violent storm that also crippled or destroyed 37 other planes. In all, 54 soldiers died on that “Black Sunday,” the largest non-combat aviation casualty toll of World War II.

Robertson said she had long-since made peace with her brother’s death when her older sister heard from the Pentagon four years ago that a New Guinea villager hunting wallaby in a dense mountain forest had spotted two sets of dog tags below the cockpit of a plane caught in the trees.

“It felt like getting socked in the stomach,” she said of hearing that his body might be recovered after so many years. “We never thought we’d again hear about it or know anything about it.”

Using DNA samples from surviving relatives, the Army finished identifying the bodies of the Royal Flush’s missing bombardiers earlier this year. Their remains were interred in a common coffin at Arlington National Cemetery in April, but Robertson set some ashes aside so her brother could be laid to rest next to their mother’s grave in Palo Alto.

“Your children aren’t supposed to go away before you,” she said. “A lot of mothers are experiencing that now.”

Because their father died when Widsteen was 11, he was the man of the house when he enlisted in the Army at age 18. Robertson recalled their mother selling the family car because her oldest child and only son, who sent his military salary home to help support his younger sisters, wasn’t around to tinker with it.

The last letter Widsteen sent home reflected his paternal role.

It was to his middle sister, who was about to get married.

“He said, ‘Do you really think you love this guy? Do you think he will take good care of you?”‘ Robertson said.

At Friday’s service, Army reservists played “Taps,” gave Widsteen a 21-gun salute and presented his family with a folded American flag and ribbons honoring his World War II service and three Asian Pacific campaigns.

Army Chief Warrant Officer John Monks said that even with the country busy fighting another war, the nation can’t afford to forget its past heroes.

“They are all those who stepped forward in our country’s hour of need so all of us can enjoy our freedoms,” he said.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard