NEWS RELEASES from the United States Department of Defense

No. 411-06 IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Missing WWII Airmen are Identified

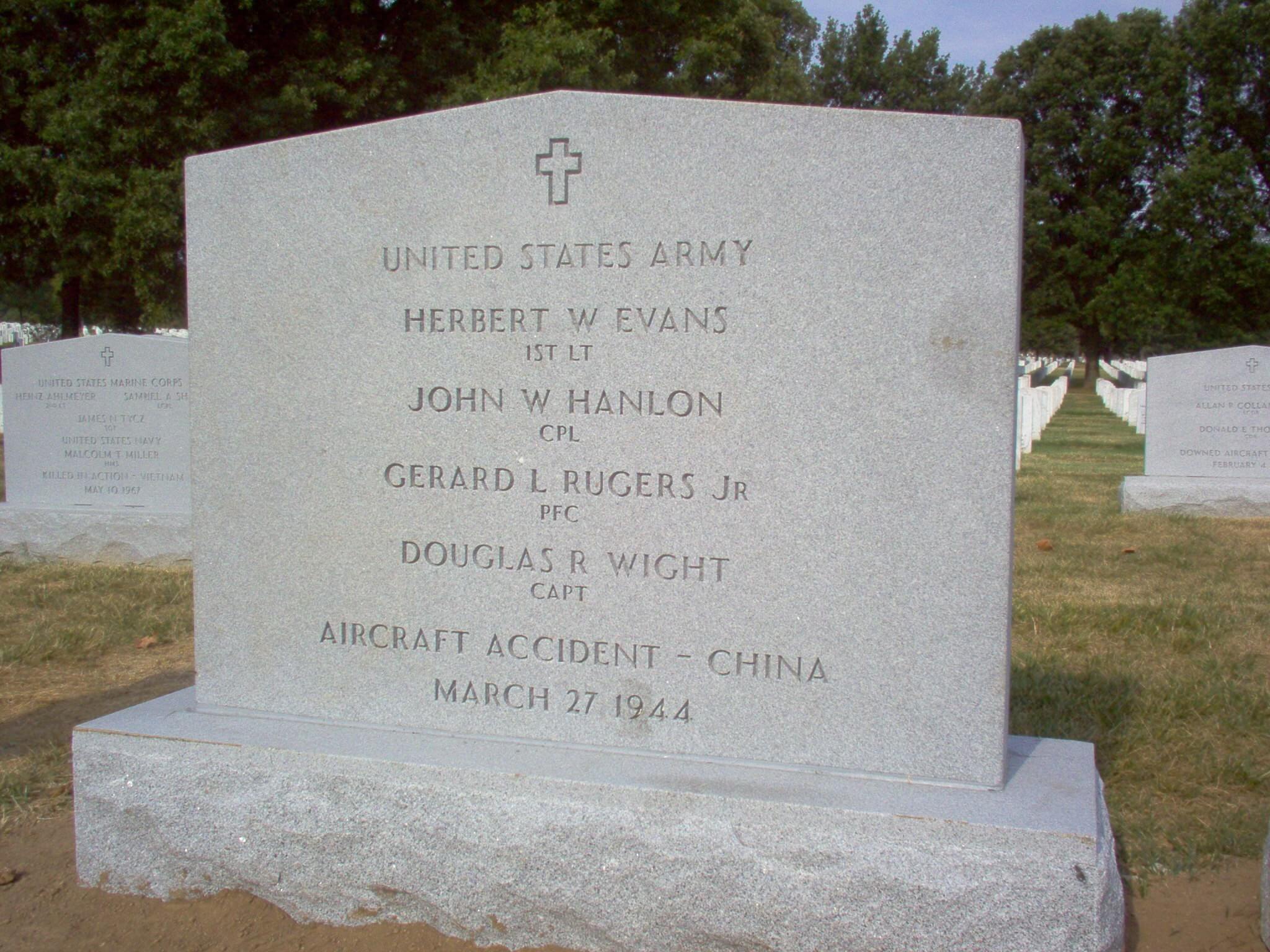

The Defense POW/Missing Personnel (DPMO) announced today that two members of a four-man Army Air Forces crew missing in action from World War II have been identified, and are being returned to their families for burial with full military honors.

The four are pilot Captain Douglas R. Wight of Westfield, New Jersey; co-pilot First Lieutenant Herbert W. Evans of Rapid City South Dakota; crew chief Corporal John W. Hanlon of Arnett, Oklahoma; and radio operator Private First Class Gerald L. Rugers, Jr., of Tacoma, Washington Evans and Rugers were individually identified, while group remains of all four will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, D.C. on Tuesday, May 9.

On March 27, 1944, a C-46 crewed by these four airmen departed a base in Kunming, China, on route to Sookerating, India, as part of the massive allied resupply missions over the Himalayan Mountains, referred to as the “Hump.” En route one of the crewmen called out for a bearing, suggesting the aircraft was lost. There was no further communication with the crew. The aircraft never reached its destination, and searches during and following World War II failed to locate the crash site.

Officials from the People’s Republic of China notified the U.S. in early 2001 that the wreckage of an American WWII aircraft had been found on Meiduobai Mountain in a remote area of Tibet. The following year, a joint U.S.-P.R.C. team, led by the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), excavated the site where they found human remains, aircraft debris and personal items related to the crew.

JPAC scientists and Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory specialists used mitochondrial DNA as one of the forensic tools to help identify the remains. Laboratory analysis of dental remains also confirmed their identifications.

Herbert W. Evans

First Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 0-740778

India-China Wing, Air Transport Command

Entered the Service from: South Dakota

Died: 27 March 1944

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

John W. Hanlon

Corporal, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 38269554

India-China Wing, Air Transport Command

Entered the Service from: Oklahoma

Died: 27 March 1944

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

AMARILLO, Texas — Army Air Corps Cpl. John Hanlon will be buried with full military honors this week, ending six decades of uncertainty for relatives who last saw the young man with the gold-toothed smile in the winter of 1944, as he headed back to fight in World War II.

Two of his brothers returned from World War II, and a nephew fought in Vietnam, but there was no word about Hanlon’s fate.

The first break in the silence for his family came in 2002, when the Chinese government notified American military officials that the wreckage of a World War II-era plane had been found on a mountainside in the Himalayas of southeastern Tibet.

Investigators went to Tibet and found the remains of four crew members, said James Pokines, a forensic anthropologist for the U.S. military’s Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command, which is in charge of recovering missing American soldiers. They returned in 2004 to recover the remains.

DNA samples were taken from members of Hanlon’s family, and Pentagon officials notified the family last fall that a match was found.

The news confirmed what relatives suspected all along, although they had held out hope that Hanlon somehow had survived all these years.

“I just kept praying that he would show up, that maybe he had been picked up as a prisoner,” said 89-year-old Cathryn Hanlon Brown.

Brown, her sister, three brothers and other family members were leaving this weekend for Washington, D.C. Hanlon will be buried Tuesday at Arlington National Cemetery, across the Potomac River from the capital.

Brown’s son, James, said family members are relieved they can lay him to rest.

“My mom and everybody has been elated,” he said. “It has brought up a lot of memories, and there have been a lot of tears shed.”

Brown, who now lives in Panhandle, recalled the last time she saw her brother in 1944.

The family threw a party for Hanlon, who was returning to the war after a short leave. The happy-go-lucky young man boarded a train in Shattuck, Okla. He flashed a big grin and tossed his sister a silver dollar as the train pulled out.

A few weeks later, on March 27, 1944, the C-46 transport plane in which Hanlon was riding crashed into a mountainside in a steep Himalayan gorge. Hanlon and his crew were running supplies from India to China.

Gerard L. Rugers, Jr.

Private First Class, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service # 39180415

India-China Wing, Air Transport Command

Entered the Service from: Washington

Died: 27-Mar-44

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal

Douglas R. Wight

Captain, U.S. Army Air Force

Service # 0-793471

India-China Wing, Air Transport Command

Entered the Service from: New Jersey

Died: 27 March 1944

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery

Manila, Philippines

Awards: Air Medal

Family and nation can finally give pilot a farewell salute

It was 1935. She was two years behind him at Westfield High School — she a sophomore, he a senior — and she barely knew him.

“I just sort of remember passing him in the halls,” she said. “The yearbook said something about him being very quiet and he should find some quiet girl.”

Decades later, long after his disappearance, she would marry his brother. And now Lois Wight will be traveling with other relatives to Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia to bury his remains.

First Lieutenant Douglas R. Wight was flying a C-46 transport on a supply mission during World War II when it crashed over a treacherous stretch of the Himalayas, known as “the hump,” in Tibet.

It wasn’t until six years ago that the wreckage was found by herdsmen and reported to the Chinese government. It then took two years to plan and carry out the rugged 16,000-foot climb into the Hima layan wilderness, where a joint U.S.-Chinese expedition recovered the remains and personal belong ings of the four-man crew. The plane was identified through tail markings, but it took several more years to identify the remains of Wight, co-pilot Herbert Evans, crew chief John Hanlon and radio operator Gerald Rugers.

The families of all four have been invited to a service at Arlington National Cemetery Tuesday to honor the lost airmen and to inter their remains and the be longings recovered with them.

“I have no idea what’s going to be buried. I heard there were belt buckles found,” said Lois Wight, who still lives in Westfield.

Burying heroes long after their deaths is nothing unusual at Arlington. Since the 1970s, the Pentagon has made a focused effort to account for those missing in military conflicts.

Rarely a month goes by without a funeral for a casualty from Wight’s era, said Larry Greer, spokesman for the Pentagon’s POW/MIA Office, and Army scientists recently identified the re mains of a World War I soldier discovered in Europe, he said.

The rites are highly ceremo nial and emotional but rarely melancholy, Greer observed.

“It’s a time where a family can finally close a chapter,” he said.

The military’s focus on retrieving the bodies of missing soldiers is a relatively new development, according to historians. It was only after the Battle of Gettys burg during the Civil War that the government made a concerted effort to bury soldiers in individual graves, each marked by a headstone, said Angus Gillespie of Rutgers University, a professor of American studies.

“The war had become unpopular, and they had put in a draft. The government felt, if it was going to ask people to volunteer, they had to recognize the sacrifice,” he said.

Holding a funeral 60 or more years after a death still makes sense, Gillespie said.

“There are so many out there somewhere, it’s kind of nice when we find one,” he said. “It doesn’t matter that members of their immediate family may be dead. That’s not the point. The point is, we are sending a message to the active-duty soldier: You will not be forgotten.”

Lois Wight never encountered Douglas Wight again after he graduated from high school. He attended Rutgers University and earned a bachelor’s degree from Columbia in 1939 before serving with the Army Air Corps.

She married his older brother, Thomas Herbert Wight, in 1982, after the death of her first husband.

Thomas Wight died four years ago, knowing his brother’s aircraft had been discovered.

“He was very pleased that they at least found the wreck age,” she said. “It was a puzzle not knowing what was going on. They (her in-laws) wondered if he ever would be found, and he was — after all those years of almost giving up on it.”

Another brother of the lost pilot is 83 and living in Bemus Point in upstate New York. Philip Wight was a 21-year-old radioman/gunner on a B-17 based in Eugland when his brother was reported missing March 27, 1944. Douglas Wight, 27, and his crew had flown from a base in northeastern India and were en route to Kunming, China, to supply Chinese troops fighting for the Allies.

What we heard was there was no evidence as to where he went down and very little information about how it happened. A lot of rumors, but nothing concrete,” Philip Wight said.

The aircraft was one of more than 500 the U.S. military lost flying the Himalayan route, which became known as “The Alumi num Trail” for the wreckage left behind.

Philip Wight described flying “the hump” as “horrible — not only mountainous, but poor visibility, fog, ice, everything. It’s the worst flying conditions in the world.” The last radio transmis sion from his brother’s aircraft was a request for directional bearings.

Philip Wight said he has mixed emotions as the ceremony at Arlington closes this chapter in family history. It’s a combination of “relief, to know what he really went through and what happened,” and “sadness — he died a young man in the service of his country.”

But the family is long past the loss, he said, and looking forward to the ceremony.

“I know it’s not going to be a sad time,” Philip Wight said. “Most of the grieving has been done 62 years ago. I think most people feel as I do, that we’ve finally put this to rest.

“We in the family are honored that we had such a brave brother. He gave his life for his country.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard