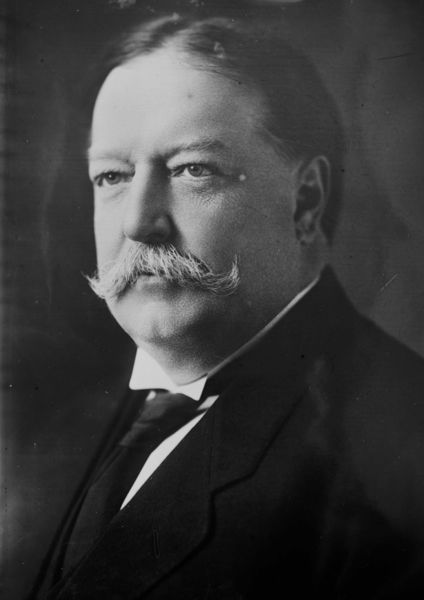

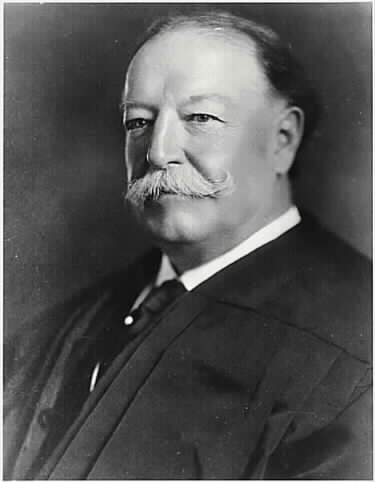

During his long government career, he served as Governor of the Philippines, Secretary of War, President of the United States and Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. He is the only man in U.S. history to have been both President and Chief Justice.

He was a large man, six-feet tall and weighing more than 300 pounds. He retired from the Court on February 3, 1930, due to ill health, and died five weeks later on March 8, 1930. His wife, Helen Harron Taft, was responsible for the stone on their gravesite, Stoney Creek Granite, 14.5 feet tall, sculpted by James Earl Frazer, it is in the Greek Stele motif. Helen Harron Taft died at home in Washington, D.C. on May 22, 1943, at the age of 83. She was the first first-lady to be buried in Arlington.

He and his wife are buried in a Special Gravesite in Section 30 of Arlington National Cemetery. He was the first of only two Presidents to be buried in Arlington.

His grand-nephew, William M. Taft, a career United States Navy enlisted man, died in May 1998 and is also buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

March 9, 1930

EX PRESIDENT TAFT DIES AT CAPITAL

SUCCUMBING TO MANY WEEKS’ ILLNESS,

FIVE HOURS AFTER JUSTICE SANFORD

END COMES AT 5:15 P. M.

Former Executive and Chief Justice Passes in Coma, Wife at Side.

HOOVER HASTENS TO HOME

President Proclaims 30 Days of Mourning for Nation-Military Funeral Planned.

BURIAL TO BE AT ARLINGTON

National Capital Is Saddened by Loss of Man Who Held the Country’s Two Highest Honors

Washington, March 8.- William Howard Taft, the only man in the history of this country to have filled both the offices of the President and the Chief Justice of the United States, died at 5:15 o’clock this afternoon. He was in his seventy-third year. His death, which was caused by cerebro-arteriosclerosis, was preceded by that of Associate Justice Edward Terry Sanford at noon.

Today also was the eighty-ninth birthday anniversary of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, oldest member of the Supreme Court.

The deaths of two of the occupants of the highest bench were peculiarly saddening to the capital. During the illness of Mr. Taft Justice Sanford had been an almost daily caller at his home. The death of Justice Sanford was quite unexpected, occurring after his collapse in a dentist’s office where he had had an ulcerated tooth extracted. Taken to his home in an ambulance, he succumbed to uremic poisoning.

President Hoover issued this evening a proclamation authorizing national mourning for thirty days for former President Taft.

Mr. Taft succumbed after a rally a week ago from what his physicians thought was certainly the last phase of his illness and this temporary recovery brought a false hope that he might linger possibly for months.

Hoover Hastens to Taft Home

President Hoover was on an automobile ride when his intimate friend passed away, and could not be notified until he returned to the White House at the same minute that Mrs. Manning was receiving the unexpected news. He immediately recalled his car and, with Mrs. Hoover, hurried to the Taft home. During a brief stay, Mr. And Mrs. Hoover consoled Mrs. Taft and Mrs. Manning and repeated their offer of every facility of the White House to lighten the burden of the many arrangements which must be made under the circumstances. The President also places at Mrs. Taft’s disposal the East Room of the White House for the funeral, but a request by Mr. Taft himself that the services be held from All Souls Unitarian Church on Sixteenth Street, of which the Rev. Ulysses Grant Baker Pierce is pastor, precluded either acceptance of this offer or a funeral in the Capitol, which had been considered a possibility. The services tentatively have been set for Tuesday, but final arrangements await the arrival of the sons from Cincinnati, when a family conference will be held concerning the details.

Burial will be in Arlington Cemetery, in accordance with the request of the family, Mr. Taft having qualified for this honor both as a former Secretary of War and as former Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy while President.

Lapsed Into Unconsciousness

In the room with Justice Taft when the peaceful end came were Mrs. Taft, who had entered it about two minutes before, a nurse, and Dr. H. G. Fuller, who had responded to the nurse’s hurried summons in the absence of Dr. Francis R. Hagner, Justice Taft’s personal physician and friend for a quarter of a century. Death came quietly, Mr. Taft sinking imperceptibly into unconsciousness, as he had done frequently during the past month, and while in it suffering stoppage of the functioning of his heart. Immediately after his passing, Dr. Hagner and Dr. Thomas A. Clayton, who had been associated with Dr. Hagner in treating the former Chief Justice, arrived at the house. They issued the following bulletin, the last of a long series to be disseminated through the White House: The former Chief Justice died at 5:15 P. M. A sudden change in his condition occurred at 4:45 P. M. from which he failed to rally. The former Chief Justice has had a less restful night and his condition is not quite as favorably as yesterday. Mrs. Taft, who had known for some time that her husband could not recover, bore the shock with the same fortitude that she had displayed in daily attending to his comfort. Mrs. Helen Taft Manning daughter of the jurist, was absent from the house when the death occurred. She returned home at 6:05 and immediately joined her mother in the home at 2215 Wyoming Avenue, the lower floor of which, banked with flowers sent by multitudes of friends bears witness to the affection in which Mr. Taft was held. The two sons of the former Chief Justice, Robert and Charles Taft, were at their home in Cincinnati. Robert having returned there a few days ago when it appeared that death might be deferred by weeks or months. Both were notified immediately and caught a train which will bring them into Washington at 9:30 o’clock tomorrow morning. Two surviving brothers of the former Chief Justice also were notified of his death and tonight are on their way here. Henry Taft was at Augusta, Ga. And Horace A. Taft at Watertown, Connecticut.

Burial With Military Honors

President Hoover designated Colonel Campbell Benjamin Hodges, his military aide, to place himself at the disposition of the Taft family in regards to arrangements for the burial at Arlington, at which full military honors will be accorded. Returning to the White House, President Hoover immediately issued his proclamation of national mourning for thirty days, canceled all White House social engagements during that period and ordered that the flags on government building fly at half-staff. This procedure is in accordance with precedent when a former President dies, although an exception was made to accord the same honors to the memory of Secretary James W. Good, who died recently. Vice President Charles Curtis is away from the city. He had canceled a week ago an engagement to speak at a dinner in Indianapolis tonight when Mr. Taft was expected to die momentarily, but had reaccepted when Mr. Taft’s condition improved. The word of Mr. Taft’s death was relayed through Washington almost instantly. First to appear at the house was Associate Justice Willis Vandevanter, who alighted from his car at 6:25 P. M. He was followed in quick succession by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, successor to Mr. Taft, and President and Mrs. Hoover. Soon a constant stream of automobiles brought persons at the house to leave their cards and expressions of sympathy. Another visitor was Bishop James E. Freeman of the Washington Cathedral, who characterized Mr. Taft as “the most loved man in a generation.”

Whole Capital Saddened

The death of Mr. Taft cast a gloom over Washington. For more than a month a silence presaging the death had hovered over the neighborhood. The blinds of the house had remained drawn and a policeman had patrolled the sidewalk to assure quiet. The district is a restricted one with little traffic, and the quietude of the house had been broken only by those friends who called at intervals to inquire as to Mr. Taft’s condition. Quartered in a house a few doors away and across the street have been newspaper men awaiting the latest physicians’ bulletins or developments in the case. This vigil was withdrawn yesterday morning when the last possibility of Mr. Taft’s dying imminently appeared to have disappeared. When his death did occur it was not sent out to the world until half an hour later, after the physicians had prepared the bulletin which was issued through the White House. Tonight, however, the air of foreboding had disappeared. The blinds on the ground floor of the house were raised and all the windows reflected the illumination of lights within, displaying the flowers which were sent as expressions of regard during the life of the recipient. Tomorrow they will be replaced by blooms which have a more solemn import.

While the visitors to the home were arriving and leaving, reporters surged over the sidewalks and photographers recorded pictorially the events surrounding the passing of an eminent figure. The disseminating of necessary information was undertaken by the White House, the closed offices being opened and George Akerson, Secretary of the President, being summoned from the golf links to organize the work. It was he who gave out the notice of funeral arrangements and made public the President’s proclamation at the White House.

Last Days of Mr. Taft

The passing of Mr. Taft ended a tragic period in which all of Washington, and, for that matter, the United States maintained a vigil of waiting for inevitable death which has been compared only with the circumstances surrounding President Wilson’s passing. From the gloomy, rainy morning of Feb. 4, on which Mr. Taft, returning from Asheville, N. C. was lifted from his private car and borne in an automobile to his residence on Wyoming Avenue, the question has not been whether the eminent jurist would die but when he would sink finally into a period of unconsciousness from which he would not awaken. The bulletins issued by his physicians, from the first one on that day, have contained frank statements that Mr. Taft was in a critical condition, but those friends of the patient who were in close touch with him realized that the most pessimistic reports were borne out in his condition. Arterio-sclerosis is the scientific name for hardening of the arteries, a condition which gradually causes a slowing up of the circulation until at last it stops entirely. Myorcarditis is a weakening of the heart of the heart which is said to accompany the other ailment. In addition the former chief justice had suffered for many years from a painful organic complaint which had treated his life on many occasions. The one mitigating factor in his last illness has been the fact that at no time has he been in pain. Neither the congenial spirit nor the famous smile were dimmed through his suffering. In his unconscious periods, which became more frequent and of greater duration during the last two weeks, his face seemed serene.

Wife Constantly at His Side

Most constant of those attending Mr. Taft was his wife, who for days at a time did not leave the house. Her care and unrelenting efforts to assure his comfort won frequent comment from all those in touch with the home. While few visitors ever were admitted to the Taft home during this illness, Mr. Taft was constantly remembered by old friends who are among the most prominent persons in officialdom. Justice Holmes, the oldest member of the Supreme Court, whose period of service antedates even Mr. Taft’s occupancy of the Presidency, visited the house on several occasions, including the first rainy day, despite the fact that his own health has not been of the best. Justice Harlan Stone, another member of the Supreme bench, who was an intimate friend of the former chief and a close neighbor, likewise visited the home repeatedly, and during the critical period of a week ago kept a servant posted at the Taft home to relay frequent news to him.

Visited Twice by Hoover

President Hoover, another intimate friend of Mr. Taft, paid two calls, marked with as much simplicity as the President is permitted to assume at the home of the former Chief Justice. The first was on February 5, when accompanied by Mrs. Hoover, he found him sitting up in bed and chatted with him for several minutes. At that time the President and Mrs. Hoover offered every facility of the White House to lessen the burdens on the Taft household occasioned by the multiple inquiries and demands surrounding the illness of such a prominent personage.

One service which the White House has given daily since then has been the dissemination of the bulletins concerning Mr. Taft which were issued twice daily by his physicians. The second visit by Mr. and Mrs. Hoover was paid on March 1, the President being accompanied also by his son, Alan Hoover. At neither time were photographers permitted to record the visit, although these watchers and reporters for press associations have been quartered in a house not far from the Taft home, continually on alert for the latest word.

Physician a Friend for 25 Years

Dr. Hagner’s ministrations have been marked with more than professional care, for in Mr. Taft he loses a friend of more than twenty-five years’ standing. For twenty years of that time they have also been associated as physician and patient. It was on Dr. Hagner’s advice that Mr. Taft took a leave of absence from the bench on January 6 to go to Garfield Hospital for treatment, following the weakening in his health as a result of attending the funeral of his brother, Charles P. Taft, at Cincinnati. He left the hospital a week later and went to Asheville for recuperation in the place where he has resided on such vacations as were not spent at Three Rivers, Quebec.

March 9, 1930OBITUARY

Taft Gained Peaks In Unusual Career

By THE NEW YORK TIMES

Twenty-seventh President of the United States and its tenth Chief Justice, William Howard Taft was the only man in the history of the country to become the head of both the Executive and Judicial Departments of the Federal Government.

Elected to the Presidency to succeed Theodore Roosevelt in 1908 by a tremendous majority, both popular and electoral, he met overwhelming defeat four years later in the political catastrophe which wrecked temporarily the Republican Party, ruptured his long friendship with Roosevelt, who had brought about his first nomination for the Presidency, and resulted in the election of Woodrow Wilson.

The worst beaten Republican candidate who ever ran for the highest office in the nation–for he received only the eight electoral votes of Utah and Vermont — President Taft left the White House with his Administration discredited, although personally he had lost little of the esteem in which he had been held by his fellow countrymen.

His appointment by President Harding as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, an office which by both temperament and training he was better fitted to hold than that of President, came as a realization of a lifelong ambition, and was received with every manifestation of popular approval. It was a “come-back” unprecedented in American political annals.

Taft-Roosevelt Break

The break between President Taft and Colonel Roosevelt, the causes of which never were fully explained, and which was followed by a reconciliation some time before the latter’s death, had far-reaching consequences, and the scars of the conflict that was caused by the formation of the National Progressive Party under the leadership of Roosevelt in 1912 still remain.

Backed by Theodore Roosevelt, then President, Mr. Taft, then Secretary of War in the Roosevelt Cabinet, gained the Republican nomination for President in 1908 without difficulty. “If they don’t take Taft, they will get me,” the comment of Colonel Roosevelt when certain Republican leaders demurred at supporting Mr. Taft for the nomination, was sufficient to bring most of the recalcitrants into line. Justice Taft’s election followed by the overwhelming majority of 321 electoral votes out of a total of 488.

Just how and when the split that was to break the long friendship between Taft and Roosevelt started never has been told with certainty. They were still warm friends when Mr. Taft assumed the Presidency, and Colonel Roosevelt left soon afterward on his hunting trip to Africa, undertaken partly with a view to removing himself temporarily from the situation and relieving the new

President of embarrassment.

It is known that some of Colonel Roosevelt’s friends at Washington did not fare as well under the new Administration as they had expected; it also is known that Mr. Taft as President did not consult Colonel Roosevelt as he had when he was in his Cabinet. It also was reported that Colonel Roosevelt felt that President Taft had not been as assiduous in developing and carrying forward the “Roosevelt policies” as the former President had expected.

Last to Acknowledge Change

In any event, it developed that by the time Colonel Roosevelt emerged from the African jungle on his way back to civilization the “break” had become an established fact, that is, established to the knowledge of everybody except President Taft. He was the last to acknowledge that Colonel Roosevelt’s feelings toward him had changed.

Friends of Colonel Roosevelt met him on his way back to this country and it was believed in Washington that they had much to do in influencing him against Mr. Taft. These men later took a prominent part in forming the Progressive Party. They had clashed with President Taft almost from the day he went into the White House.

The feud between Richard A. Ballinger, then Secretary of the Interior, and Gifford Pinchot, then Chief of the Forest Reserves and later Governor of Pennsylvania, over the governmental policy in regard to public lands, was believed to have widened the breach between President Taft and the friends of Colonel Roosevelt. The President removed from office Mr. Pinchot, who had been one of the leading members of what was known as President Roosevelt’s “kitchen cabinet.”

Then, too, a wave of so-called “progressivism” was sweeping over the country, and it was alleged that President Taft had yielded too much to the counsel of the conservative leaders of the Republican Party.

Soon after his return to this country from Africa in 1910, Colonel Roosevelt called on President Taft at the “Summer White House” at Beverly, Mass. According to those who witnessed the meeting, there was an attempt by both men to display the same old cordiality, but it was palpably on the surface only, and there was apparent a distinct feeling of constraint. There were few meetings after that and it became evident in the Spring of 1912 that President Roosevelt would be a candidate for President.

Refused to Credit Reports

Long after Colonel Roosevelt had informed his friends that he was opposed to the renomination and re-election of President Taft, the latter refused to credit such reports. When the true state of affairs became evident, Mr. Taft would reply to those who said to him “I told you so” with one of his tolerant smiles. Never did he criticize Colonel Roosevelt and invariably referred to him as “The President.”

“I learned to call him that while I was in his Cabinet,” Mr. Taft said on more than one occasion, “and, somehow or other, I can’t think of him in any other light.”

Colonel Roosevelt’s decision to try for the Republican nomination for President and to “throw his hat into the ring” in response to the request of seven Republican Governors is known to every reader of political history.

The Republican National Convention at Chicago in 1912, over which Elihu Root presided, balked Colonel Roosevelt’s ambition. Although the latter had shown remarkable strength in the States then having direct primaries, the majority of which he captured, the Republican national organization succeeded in holding a majority of the delegates in line for President Taft and he received 651 votes, 111 more than the majority necessary to nominate, to 107 for Colonel Roosevelt, with 344 Roosevelt supporters not voting.

Supporters of Roosevelt charged that the National Committee had gained control of the convention for President Taft by manipulating the contests. Most of them bolted the convention and joined in the formation of the National Progressive Party, the movement that split the Republican Party in two and brought about the election of Woodrow Wilson.

Mr. Taft’s remarkable record in public office had led to the expectation that he would make a great success of his administration as President, and it was believed by many afterward that the reason he failed, at least on the political side of his Administration, was that his temperament was judicial rather than executive.

Ohio Taft’s Native State

Mr. Taft was born Sept. 15, 1857, in Cincinnati, Ohio, the son of Alphonso Taft, Secretary of War and Attorney General in President Grant’s Cabinet, and Louisa Torrey Taft.

After graduation from Woodward High School, Cincinnati, Mr. Taft entered Yale University, where his father had been a student. He graduated from Yale in 1878, the second in a class of 121. Although athletically inclined–he was stroke of his class crew and a famous wrestler–he devoted most of his time to study. His standing among his college mates is indicated by the fact that he was known by them while at Yale and forever afterward as “Old Bill” Taft.

After college Mr. Taft immediately began the study of law in connection with newspaper work on The Cincinnati Commercial, and on graduation from the Cincinnati Law School in 1880 he started the practice of law. The next year he was appointed Assistant Prosecutor of Hamilton County, and in 1882 was appointed Collector of Internal Revenue, a place paying $10,000 a year and a most lucrative position for a youth of 25.

The young lawyer resigned that place, for his desire never was for money, to resume the practice of law, and from 1887 to 1890 he was a Judge of the Superior Court of Ohio. In 1890 he was appointed Solicitor General of the United States by President Harrison. His argument and briefs in the Bering Sea and tariff cases brought him wide notice and a national reputation, and in 1892 he was appointed a Judge of the newly created Circuit Court of Appeals, Sixth Circuit, on which he served until 1900. It was while he was holding this post that Mr. Taft first met Theodore Roosevelt, the latter being a Civil Service Commissioner at the time.

Decisions as Circuit Judge

As a Circuit Court Judge, Mr. Taft had occasion to make certain decisions concerning railroads, corporations and organized labor that were of far-reaching importance. In the case of Moore vs. the Bricklayers’ Union he declared secondary boycotts illegal and held that, although labor had the right to organize into unions, these unions must refrain from acts injurious to organized society. When Eugene V. Debs, many times Socialist candidate for President, tried to tie up railroad traffic during a strike in 1894, Mr. Taft granted an injunction to prevent this against Debs’s agent, F.W. Phelan.

From 1896 to 1900 Mr. Taft was Dean and Professor of Law at the University of Cincinnati. In 1900 Mr. Taft resigned his judgship to become the Chairman of a commission appointed by President McKinley to institute civil government in the Philippines, although he had been opposed to the annexation of the islands as a result of the Spanish-American War. He took this appointment with reluctance, telling President McKinley, also an Ohioan, that his ambition was to become a Justice of the Supreme court of the United States.

“You will be the better judge for this experience,” President McKinley replied, inducing him to take the appointment.

A short time later Mr. Taft became the first Civil Governor of the Philippines. In his four years’ residence in the islands he attained a reputation as an able Colonial administrator. Order having been gradually effected, he began to introduce the rudimentary forms of civil government. The government was organized, good roads built, postoffices established, schools and American teachers introduced, banks founded and civic improvements made. Sanitation under American direction removed much of the danger of epidemics of contagious diseases.

In 1902 Mr. Taft visited Rome to negotiate with Pope Leo XIII terms for the purchase of the friars’ lands in the Philippines. He induced Congress to appropriate $7,239,000 for this purpose, and then sold the lands to tenants and inhabitants on easy terms.

Won the Trust of Filipinos

He regarded the Filipinos as unprepared to govern themselves, and urged that they should be educated before the United States contemplated giving them independence. He advocated free trade and the development of sympathy between them and the Americans. He won the trust of a large part of the natives, who asked him to remain when he was offered a place on the Supreme Court bench in 1903.

In 1904 Mr. Taft succeeded Elihu Root as Secretary of War in President Roosevelt’s Cabinet. It was said the reason that he took the post was because the Philippines were under the jurisdiction of the War Department, and he felt he still would have opportunity to improve the condition of the inhabitants of the islands.

It was as Secretary of War that Mr. Taft first gained his reputation as the “great American traveler,” which he sustained after his election to the Presidency. He became the spokesman and field representative of the Roosevelt Administration on practically every important matter that required the dispatch of a representative from Washington, going on many important trips to various American cities and to foreign countries.

In 1906 Mr. Taft was temporarily the Civil Governor of Cuba, after the intervention of the United States in that year to restore order. In 1907 he visited the Panama Canal Zone to familiarize himself with conditions there, and it was under his general direction that the construction of the canal was carried on. In 1907, also, he visited the Philippines to be present at the opening of the Legislative Assembly, the first step of the Filipinos toward self- government. He then went to Japan to confer with representatives of the Government of that country in regard to the problem of the Japanese in the United States and settled it satisfactorily for the time. Then he proceeded to China, where he undertook important negotiations relative to a Chinese boycott of American goods, and visited Russia before returning to the United States. The then Miss Alice Roosevelt and the man to whom she was married later, Nicholas Longworth, were members of his party.

Takes Office as President

With a record of remarkable achievement in his own field Mr. Taft went into the Presidency after a long term of holding offices, which were, for the most part, appointive. After he was installed in the White House many of his most loyal friends realized that perhaps his training had not been altogether of the right sort, from a political point of view. Mr. Taft had not been reared in the school of practical politics. He had not rubbed elbows with the party workers or fought his way up through the party ranks. Consequently, they felt, he lacked that keen insight into the motives and methods of practical politicians which many of his predecessors had possessed and used with effectiveness.

Public office had always sought Mr. Taft up to his campaign for the Presidency. He could not understand the thirst for office and the demands for places on the public payroll. In all his previous career he had never held an office that carried with it any political patronage of consequence, and so was unprepared to meet the rush for patronage that began when he took office as President.

Mr. Taft often said himself that he felt a lack of that character of political training which would have thrown him into closer contact with the masses of the people. He had never been district leader, Alderman, Mayor or legislator. His training had been judicial and his circle of contact small. In the Philippines he had come in contact with the people there and exercised a wonderful influence for good over them. But he felt he did not know enough of his own people. When his extensive traveling was once criticized, Mr. Taft said to a friend:

“It seems to me that I ought to travel as much as I can. I have seen very little of the people in spite of my long years in office, and the people have seen very little of me. I thought that by traveling I could give them a chance to look me over and see what manner of man I am. Comparatively few people get to Washington, and yet I cannot but feel that a majority of the people would like to see the man who for the time being is the head of their Government.”

In all his trips Mr. Taft insisted that an automobile parade be part of the program. He wanted to be seen by as many people as possible. In doing this Mr. Taft broke all Presidential records for traveling and set a mark that will probably stand for some years to come. An account was kept by the White House staff of all his journeys while President; this computation showed a total of 114,559 miles. He was the first President to introduce the automobile in official life at Washington and became very fond of motoring.

Mr. Taft had no patience with office-seekers, and to his mind the fact that a man sought office seemed to unfit him for that office. He turned many faithful party workers away empty-handed, and soon he was in the political hot water that bubbled during most of his Administration. He took many of his trips just to get away from the office-seekers. He declared that this was the only way he could get a moment’s rest from them. The Secret Service men who accompanied him were warned as much against office-seekers as they were against “cranks.”

Mr. Taft’s judicial mind led him to underestimate the value of publicity in the conduct of his Administration. He read few newspapers and did not appreciate their influence on public opinion. He had the objection of the judge and lawyer to discussing matters in the press. This lack of interest in newspapers and misunderstanding of the benefit of newspaper publicity frequently caused him to delay the preparation of messages and State papers until it was too late to mail them throughout the country, and many of the smaller newspapers of the country carried only telegraphic summaries of some of his most important utterances.

Assailed by “Muck-Rakers”

The so-called “muck-raking” magazines were in their heyday during the Taft Administration, and practically all of these at times found fault with Mr. Taft for his way of conducting public affairs. Mr. Taft seldom replied to them.

“Oh, what’s the use?” he would say. “Whatever I say or do is sure to be misconstrued or twisted around in such a manner that even I will not be able to recognize my own motives.”

The feeling that he was a party man and owed gratitude to the leaders of the Republican party for nominating him for and electing him to the Presidency led Mr. Taft to accept the counsel of the Republican leaders at Washington, and he was criticized for too great intimacy with Senator Aldrich and Speaker Cannon, who were regarded as reactionaries by the progressives. Mr. Taft, it was reported, was not particularly fond of Speaker Cannon, but considered the Speaker as the leader of the Republican majority in the House of Representatives. He sincerely admired Senator Aldrich and had great confidence in him.

Mr. Taft, however, believed in the sacredness of the three departments of the Government — executive, legislative and judicial — as established by the Constitution. He did not believe that he had a right to interfere with the prerogatives of the legislative branch by dictating what Congress should do, although precedents for such interference had been set at the White House.

An illustration of this attitude of Mr. Taft was found in his approval of the Payne-Aldrich tariff bill. Mr. Taft, it was reported, did not believe the bill was all it should be, but considered it better than the existing tariff law and believed it met in large degree the platform promise of his party to reduce the tariff.

Opposed by Progressives

Mr. Taft was bitterly assailed by the “Progressives” for his defense of this bill, and particularly for his Winona speech on it. The controversy which followed this speech and the “reading out” of the Republican party of those who opposed Mr. Taft on the tariff, undoubtedly had a part in bringing about the break in the party which developed in 1912. Scandals connected with the Department of Agriculture brought the administration into further disfavor and encouraged the “progressive” movement.

Mr. Taft’s championship of the proposed reciprocity treaty with Canada in 1910 and the adoption of it by the aid of Democratic votes was nullified in the public mind by the refusal of Canada to accept it. His vetoes of so-called tariff reform bills in 1911 were seized upon by his opponents in the Republican party as giving further evidence that he had become a “reactionary,” and was failing to keep the party platform pledges.

In 1910 and 1911 he made a notable effort to secure the ratification of arbitration treaties which had been negotiated with Great Britain and France, and was thereafter known as one of the foremost advocates of world peace and arbitration.

Turning Point in Political Career

Perhaps the most trying time in Mr. Taft’s political career was in September, 1909. In the middle of that month he left Washington for a tour of the West, although his sciatica at that time was particularly bad. He arrived in Winona, Minn., on Sept. 17, when that district was seething over the Aldrich- Payne tariff bill favoring downward revision. Undeterred by popular sentiment there he openly defended the measure and announced that he would support Representative James A. Tawney, Chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, then on the defensive because he had not voted against the bill.

“I am not here to defend those who voted for the Payne bill, but to support them,” the President said in his speech: “On the whole I think that the Payne bill is the best tariff bill that the Republican party has ever passed; that in it the party has conceded the necessity for following the changed conditions and tariff rates accordingly.

“This is a substantial achievement in the direction of lower tariffs and downward revision and it ought to be accepted as such.”

The speech created an uproar all over the country. Newspapers were bitter in their attack on it and their comment opened the way for the split in the Republican party, resulting in the Bull Moose organization headed by former President Roosevelt. It shattered Mr. Taft’s hopes for re-election.

Asks Prayers to Carry Him Through

He did all he could to keep the party in a solid unit, but when his efforts failed he proved his courage by boldly reasserting his stand on the tariff question while campaigning in the West in 1911. At Waterloo, on Sept. 28, he said:

“There are many, I among them, who believe that protection in the past has been too high and that it is possible to lower the tariff without interfering with business.”

At Des Moines and at Ottumwa he again stanchly defended his tariff views and boldly reasserted that he favored a lower wool duty. The criticism leveled against him began to tell and he showed signs of weariness. Just before continuing his tour he said in a talk to newspaper men:

“I am starting on a long trip, gentlemen, and I ask your prayers for both my mental and physical well-being. Sometimes when I contemplate this trip I hold my breath, but being in I am going through with it.”

One of Mr. Taft’s closest friends once said of him:

“He is so clean in his own mind that he cannot see anything unclean in another. His refusal to employ the usual petty tricks of the professional politicians, the big-hearted indulgence with which he treats those who deliberately misrepresent him, his willingness to suffer himself rather than use the great power of his office against an individual–to rest under a false light rather than strike back in the heat of passion and thus risk the chance of committing an act of injustice–have won for him the distinction of being a poor politician. Mr. Taft will never understand that in politics it is often necessary to be unfair, unjust and to bring into play the ruthless rule of the survival of the fittest.”

Along this line Mr. Taft once said: “To be a successful latter-day politician it seems one must be a hypocrite. I do not understand how some of the ‘practical politicians’ can come to my office and tell me just what they feel at heart and then get up on the floor of Congress and prate about something exactly to the contrary. That sort of thing is not for me. I detest hypocrisy, cant and subterfuge. If I have got to think every time I say a thing what effect it is going to have on the public mind; if I have got to refrain from doing justice to a square and honest man because what I may say may have an injurious effect upon my own fortunes, I had rather not be President. When I have a thing to say of particular interest to a particular people, and I am quite sure they won’t agree with me, I like to say it face to face and fight it out right then and there.”

Mr. Taft was often called the most human President who ever sat in the White House. The mantle of office did not hide his winning personality in any way. He was always the same to his friends. Not quick to make friends in a general way, Mr. Taft became extremely fond of those with whom he was more intimately associated. He loved company. He and Mrs. Taft entertained liberally at the White House. Under the Taft regime the State receptions became new things. Formerly, the guests had formed into lines, hurried through the reception and left. Mr. Taft did not like this. He felt that the reception guests were his guests. So he ordered supper served at the State receptions and there was always dancing afterward.

On his retirement from the Presidency in 1913 Mr. Taft became Kent Professor of Law at Yale University, and the same year was elected President of the American Bar Association.

During the eight years of his retirement in private life Mr. Taft lived in New Haven. Although as President he had failed to profit by newspaper publicity, he found the press a valuable medium of presenting to the people his views on questions of national importance and returned to writing for the newspapers, his first serious work having been as a newspaper reporter.

Mr. Taft did not confine his advocacy of arbitration as a method of settling international disputes to writing but went upon the lecture platform, and in the heat of the debate over the League of Nations he appeared on the same platform with President Wilson to urge approval of the Versailles Treaty.

His Work in the War

While at New Haven Mr. Taft was President of the League to Enforce Peace. He was a member of the National War Labor Board during the war. Although an advocate of peace, he strongly favored conscription, once the United States had entered the world conflict, and pleaded that this country should fight no “finicky” war. He feared the war would be long, but was for fighting it out to a finish, or until the Kaiser lost his throne. In a speech in May, 1917, Mr. Taft said:

“We are in this war to say to Mr. Hohenzollern and Mr. Hapsburg, ‘You’ve got to get out, the same as Mr. Romanoff.’ If Emperors Charles and William abdicated tomorrow we would have peace in two weeks. That is what we are in the war for. We have nothing to do with the politics of Europe, but we are going over there because we are for the right and are willing to fight for it.”

In a speech in Indianapolis in August of the same year Mr. Taft said:

“In vindicating the rights of our citizens against Germany’s brutality it may cost us millions of lives, and there are those who would emphasize the discrepancy between the loss of two hundred American lives by Germany’s act and the sacrifice of a million in resenting it. This is to ignore principle and make a nation’s conduct in defending its rights and upholding its honor and protecting its citizens dependent upon the question of how much it costs.”

Mr. Taft’s lifelong ambition to become a Supreme Court Justice, realized by his appointment as Chief Justice by President Harding, was indicated by an incident long before he was mentioned as a candidate for President. The incident occurred at one of the receptions in the White House during the Roosevelt Administration, in the course of a talk in which Mr. and Mrs. Roosevelt and Mr. and Mrs. Taft took part. Colonel Roosevelt, in predicting what the future held for Mr. Taft, declared that eventually he would be called to one of the two highest positions in the country.

“Make it Chief Justice,” said Mr. Taft.

“Make it President,” said Mrs. Taft.

More than once during the four years he served as Secretary of War he wavered between accepting a place on the Supreme Court bench and continuing in politics, with the Presidency practically assured to him. It was generally understood that President Roosevelt, while offering Secretary Taft a place on the bench, advised him not to accept it in view of his chances for the White House. Once when such a position was offered to him he went from Washington to New York and held a consultation with a brother who persuaded “Brother Will” that he should stand in line for the Presidency. It came to pass that when Mr. Taft became President he had the duty practically of reorganizing the Supreme Court. He made six appointments in a court of nine. One of these appointments was the elevation of Justice White, a Southern Democrat, to the Chief Justiceship. He appointed also Justices Lurton, Hughes, Lamar, Van Devanter and Pitney. Politics had nothing to do with Mr. Taft’s selections for membership on the Supreme Court bench.

At Work on the Bench

From the time he became Chief Justice Mr. Taft strove to improve the machinery of the court to expedite the vast amount of litigation constantly before it and to lessen the law’s delays. With this end in view he mace a trip to England in 1922 go study the English courts and learn how they disposed of a large number of cases expeditiously.

This trip was in response to an invitation from Sir John A. Simon, then head of the English bar and a former Attorney General of Great Britain. While making his study of the English courts Mr. Taft sat on the bench with the Judges and was made an Honorary Bencher of the Middle Temple, an honor that had been conferred previously on two American Ambassadors, Joseph H. Choate and John W. Davis.

Mr. and Mrs. Taft were received by King George and Queen Mary and members of their family in the picture gallery of Buckingham Palace half an hour before their formal court reception. At this reception Mr. Taft received the honors accorded to former Chiefs of State of European powers, and sat in his judicial robes at the right side of the King, and Mrs. Taft sat at the left side of the Queen.

A Hard-Working Chief Justice

After his return from England the Chief Justice set himself to the task of clearing up court congestion, and each session of the Supreme Court since then has disposed of an unusually large number of cases. The 1926-27 session handled 1,100 cases, more than a hundred of which entailed decisions by the court.

Mr. Taft, worn by ill health and the pressure of his judicial duties, resigned from the Supreme Court bench Feb. 3, 1930, and was succeeded as Chief Justice by Charles Evans Hughes.

Both as President and Chief Justice Mr. Taft’s personality endeared him to all, even those who opposed him politically. His infectious chuckle and good nature made him a delightful companion. He kept himself fit by daily exercise, walking whenever possible. He enjoyed golf, and played when not prevented by his duties.

Mr. Taft married Miss Helen Herron of Cincinnati and had three children — Robert, Helen and Charles. His brothers are Henry W. Taft, a leading lawyer of New York City, and Horace Dutton Taft, headmaster of the Taft School at Watertown, Conn. Charles P. Taft, editor and publisher of The Cincinnati Times-Star, who died in 1929, was a half-brother.

Mr. Taft’s Last Illness

It became known on Jan. 6 that Chief Justice Taft had been forced to suspend his work in the Supreme Court because of illness which had been aggravated by an accident during the Summer at his home in Murray Bay, Canada. The next day he entered the Garfield Hospital at Washington for rest and treatment till Jan. 14, when he entrained for Asheville, N.C. He strode to his car with his old-time easy swing and seemed to be on the way to recovery.

On Jan. 24 he was reported as much improved in health, and it was disclosed that he was taking brisk walks as well as long rides in the country about Asheville. Three weeks later, however, a change for the worse occurred, and on Feb. 3, a few hours after his resignation as Chief Justice was announced, he was placed on a train for Washington.

Upon his arrival at the capital the next day he was carried from the train and borne in an automobile to his home. A bulletin issued by his physicians that night revealed the seriousness of his condition.

After a few days the patient made a little progress, but toward the end of the month he failed to maintain gains and gradually lost ground. On Wednesday, Feb. 26, a decided turn for the worse took place. Mr. Taft became weaker as the hours passed, and by noon of the next day the physicians gave up hopes for his recovery. Since then he had been slowly sinking toward the end.

Former President William Howard Taft

State Funeral

8-11 March 1930

After a long illness William Howard Taft, at the age of seventy-two, died at his home in Washington, D.C., late in the afternoon of 8 March 1930. Mr. Taft, the only man to have held both the office of President and of Chief Justice of the United States, was accorded a State Funeral in Washington with full military honors.

The responsibility for arranging and conducting the funeral was assigned to the Commanding General, 16th Brigade, stationed at Fort Hunt, Virginia. President Herbert Hoover meanwhile appointed his own aide, Col. Campbell B. Hodges, to assist the Taft family and help coordinate funeral arrangements. According to plans the ceremonies, all scheduled for 11 March, were to begin at 0900 when Mr. Taft’s body was to be escorted from his residence to the Capitol to lie in state on the Lincoln catafalque in the rotunda until noon. A procession would then form to accompany the body to All Souls’ Unitarian Church for the funeral service. President Hoover had offered the East Room of the White House for the service, but Mrs. Taft declined since her husband had asked that it be held in the church of which he was a communicant. Dr. Ulysses G. B. Pierce, pastor of the church and long-time friend of Mr. Taft, was to conduct both the funeral and the graveside service. The members of the Supreme Court were to be honorary pallbearers.

At the request of the family, burial was to be in Arlington National Cemetery. Mr. Taft would be the first President buried there. Following the funeral service, a motor procession without military escort was to accompany the body to the Fort Myer Gate of the cemetery. There a military escort was to meet the motorcade and conduct it to the gravesite, a 2,500-square-foot plot in the northeastern area which held few graves but was well landscaped. Mrs. Taft and her two sons and daughter, accompanied by Colonel Hodges and Colonel Charles G. Mortimer, the officer in charge at Arlington, had visited the cemetery on 9 March and selected the site.

Extensive military honors were scheduled after President Hoover on 8 March proclaimed a thirty-day period of national mourning and formally directed the Secretary of War and Secretary of the Navy to render “suitable military and naval honors” on the day of the funeral. As prescribed in existing regulations, all Army posts possessing the necessary equipment prepared to fire thirteen guns at reveille, one each half hour thereafter until retreat, and then a 48-gun salute to the Union on Monday, 10 March. This was the salute customarily fired upon receipt of news of the death of a President or ex-President except, as in the case of Mr. Taft, when the notice was received on a Sunday.

Also by established custom, and as specifically directed by Secretary of War Patrick J. Hurley through Army Chief of Staff General Charles P. Summerall, Army posts were to fire twenty-one minute guns at 1430 on 11 March, the time scheduled for the end of the funeral service. Flags were to be displayed at halfstaff, colors and standards were to be draped in mourning, and all officers were to wear “the usual badge of military mourning around the left sleeve of the uniform coat and overcoat and on the saber” for thirty days. Similarly, Navy instructions prescribed that on the day of the funeral “the ensign at each naval station and on board each vessel in commission be displayed at half mast and that a gun be fired at half-hour intervals from sunrise to sunset at each naval station and on board flagships and all saluting ships acting singly.” Officers of the Navy and Marine Corps also were to wear mourning badges for thirty days.

Although existing regulations established the military honors to be rendered during the ceremonies in Washington, the size of the military escorts in the funeral of a former President was left to the Secretary of War. A squadron of cavalry (two troops), it was decided, would escort Mr. Taft’s body from the Taft home to the Capitol. The main procession from the Capitol to the church was to include two service bands, a battalion of infantry, a battalion of field artillery, a battalion of marines, and a company of bluejackets. The escort commander, another choice left to the Secretary of War, was to be Major General Fred W. Sladen, the commanding general of the Third Corps Area, with headquarters in Baltimore, Maryland.

At the cemetery, a squadron of cavalry and a mounted band were to escort the motorcade from the gate to the gravesite. A service band, a cavalry regiment, less one squadron, a battalion of engineers, and a company of marines were to stand in formation at the graveside service.

Almost all the ceremonies involved the 3d Cavalry Regiment, the “President’s Own,” stationed at Fort Myer, Virginia, after World War I and consistently called upon to render funeral honors. Besides furnishing the cavalry contingents of the escorts, the regiment was to supply the caisson and caisson detachment, four of eight body bearers (four from the Army, two from the Navy, two from the Marine Corps), half the guard of honor at the Capitol (twenty from the Army, ten from the Navy, ten from the Marine Corps), and the saluting battery, firing party, and bugler at the cemetery.

The 3d Cavalry alone was to provide the escort from the Taft residence to the Capitol and from the cemetery gate to the grave. In the main procession from the Capitol to All Souls’ Unitarian Church, the escort commanded by General Sladen was to include the U.S. Army Band and the 1st Battalion, 16th Field Artillery, from Fort Myer, Virginia; the 3d Battalion, 12th Infantry, from Fort Washington, Maryland; the US Marine Band and a battalion of marines from the Marine Barracks, Washington; and a company of bluejackets from the Naval District Washington, in that order of march. At the grave, the US Navy Band; the 3d Cavalry Regiment, less one squadron; a battalion of the 13th Engineers from Fort Humphreys (later Fort Belvoir), Virginia; and a company of marines were to form a hollow square around the perimeter of the large gravesite as a guard of honor during the graveside service.

In a misty rain, the 2d Squadron, 3d Cavalry, caisson detachment, and body bearers reached the Taft home at 2215 Wyoming Avenue, N.W., shortly before 0900 on 11 March. Facing the residence from the opposite side of the street, the mounted troops formed a front as the body bearers brought the casket from the house and secured it on the caisson.

Neither officials nor members of the family rode in the procession to the Capitol. With Metropolitan Police leading the way and the caisson between Troop E in front and Troop F to the rear, the procession made its way to the Capitol via Connecticut Avenue, Massachusetts Avenue, 16th Street, H Street, Madison Place, East Executive Avenue, Treasury Place, and Pennsylvania Avenue. Rain fell heavily as it moved over the northeast Capitol driveway to the East Plaza.

After the casket was carried into the rotunda and an honor guard, commanded by Captain Frank Goettge, a White House aide, was posted, an hour and a half remained of the scheduled period of lying in state. Some 7,000 persons in two lines filed by during that time, despite interruptions each fifteen minutes when a new honor guard relief took post.

At noon the casket was taken from the rotunda to the caisson on the East Plaza, where the entire escort had formed for the procession to the church. The Army Band led off, followed by the caisson and the remainder of the escort. As in the morning ceremony, officials and members of the family did not ride with the procession. As the column retraced its morning route as far as 16th Street, then turned north to All Souls’ Unitarian Church at Harvard Street, a heavy downpour of rain with strong winds made it difficult for the escort troops to maintain a precise step and formation. Despite the weather, the public lined the entire route as the procession, marching to the slow tempo of Chopin’s “Funeral March,” spent almost two hours in reaching the church.

Considerably before the arrival of the cortege and escort from the Capitol, some 900 people had filled All Souls’ Unitarian Church. Orderly seating was assured by Army officers acting as ushers under the direction of Charles Lee Cooke, the ceremonial officer of the State Department. Among those in attendance were President and Mrs. Hoover, Vice President Charles Curtis, cabinet members, committees of the Senate and House of Representatives, the Chief justice of the United States and associate justices of the Supreme Court (the honorary pallbearers), state governors, Army and Navy officials, and many members of the diplomatic corps.

Mrs. Taft and her family entered the church shortly before 1400, just ahead of the arrival of the procession. As the cortege reached the canopied entrance to the church a historic bell in the church steeple, made at the Paul Revere Foundry and presented to the church in 1822,tolled the message of Mr. Taft’s passing, just as it had tolled the death of every President since 1822.

Doctor Pierce, as Mr. Taft had requested, omitted any eulogies from the funeral service. The half-hour program included a processional, prayers, hymns, and readings from the poems of Wordsworth and Tennyson. Network radio systems broadcast the service over nearly a hundred stations throughout the nation, including some with short-wave transmitters that were monitored regularly in foreign countries.

At the conclusion of the service, Mr. Taft’s casket was borne from the church and placed in a hearse for the motor procession to Arlington National Cemetery. The military units of the escort from the Capitol, which had remained information outside the church during the funeral service, stood as a guard of honor while the motorcade formed and departed. The procession, escorted only by motorcycle police, included a hundred cars. The leading car carried Doctor Pierce and the second the honorary pallbearers. The hearse came next, and was followed by cars bearing the Taft family, President Hoover’s car, and the cars of high government officials. In some thirty minutes, the motorcade moved south on 16th Street and New Hampshire Avenue, west on Pennsylvania Avenue and M Street to Key Bridge (Memorial Bridge and Memorial Drive were under construction at the time), then to Fort Myer and through it to the cemetery’s Fort Myer Gate.

The rain had stopped by the time the motor procession reached the gate. The 3d Cavalry’s saluting battery, positioned near the roadway in the cemetery, signaled the arrival by firing the first of twenty-one minute guns. Over the twenty minutes in which this salute was fired, the 3d Cavalry’s mounted band, at reduced cadence, and the 1st Squadron, which had formed at the gate, escorted the motor procession to the gravesite.

At the grave the remainder of the 3d Cavalry (dismounted), the Engineer battalion, and the Marine company, all together about a thousand men, already were in the hollow square guard of honor formation. The honor guard presented arms, ruffles and flourishes were sounded, and the Navy Band played a hymn as the casket, followed by the Taft family and dignitaries, was borne to the canopied grave. When Dr. Pierce concluded the brief service, a 3d Cavalry firing party of sixteen men delivered the traditional three volleys. The battery meanwhile had begun the final 21-gun salute. At the end of the salute, taps was sounded for the twenty-seventh President and tenth Chief Justice of the United States.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard