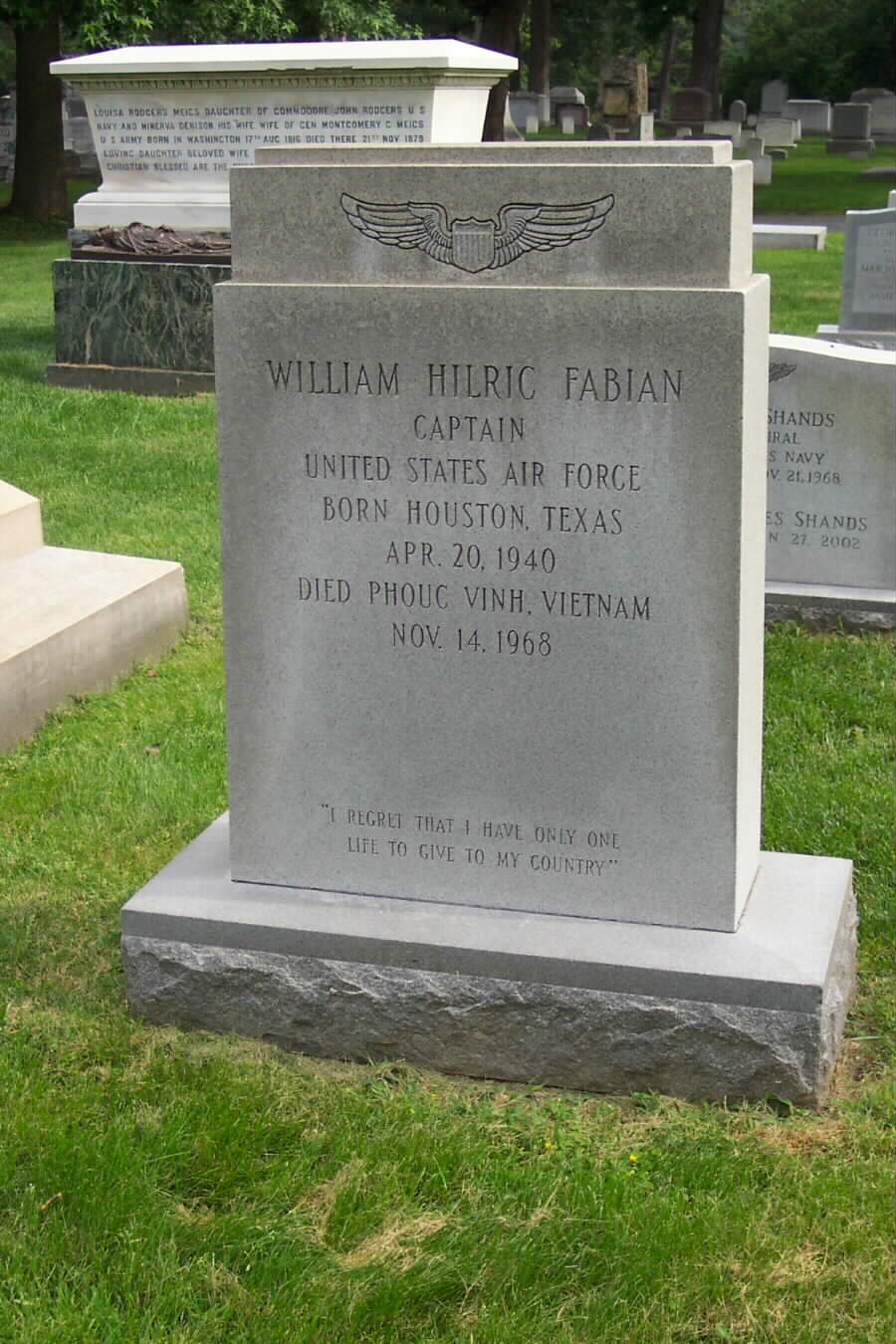

His private memorial in Section 1 of Arlington National Cemetery reads:

Captain, United States Air Force.

Born at Houston, Texas, April 20, 1940.

Killed In Action: Pholic Vihn, Vietnam, November 14, 1968.

“I regret that I have only one life to give to my country.”

Wednesday, November 27, 2002

By Stacey Wiebe

Courtesy of the Atwater (California) Signal

Although its stay at the Castle Air Museum was short-lived, the Wall That Heals, a half-size replica of the Vietnam War Memorial, drew more than 20,000 guests and had quite an impact on those in search of medicine for lasting wounds.

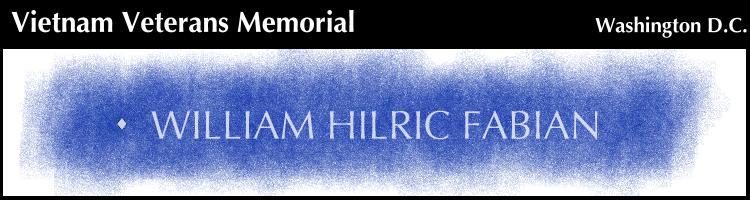

The 250-foot exhibit made a pit stop in Atwater for viewing November 14-17, when visitors from as far north as Oregon stopped to pay their respects to the 58,220 names etched into the wall’s 24 panels.

“It was a huge success,” said Amy Rose, events and marketing coordinator for the Castle Air Museum. “It helps people who haven’t found closure at least begin that process. I wasn’t in the war, but I saw how people reacted.”

More than 1,000 guests turned out to welcome the wall last Thursday during its opening ceremony. Another 500 gathered for the closing ceremony on Sunday.

Mementos left by guests at the wall and collected by some of the 240 volunteers at the memorial will be on permanent display at the museum.

Melanie Fabian, who helped guests find the names of the dead as a volunteer, was 2 years old when her father, Captain William Hilric Fabian, died in Phoug Vinh, Vietnam.

“It was a fabulous, heart-warming experience,” said Fabian, 36. “Who would have thought that with all the pain involved it would have been such a positive and rewarding experience?”

Though Fabian never met her father, a pilot in the Air Force who flew low over the thick foliage of battlegrounds to spot the enemy, the experience of visiting the wall helped her deal with the pain of his loss.

Visiting the memorial seems to have helped others heal as well.

Fabian said she saw a guest, a Vietnam veteran, who “couldn’t seem to draw himself away from a fellow soldier’s name.”

“He would stare at the name for 10 minutes and then walk away. He went back six or seven times and would just stare.”

Fabian convinced one of her friends, a veteran, to visit the wall despite his unwillingness in light of the treatment of Vietnam veterans after returning home to American soil.

“He said, ‘It’s too little, too late,’” Fabian said, “but he came.”

The life of Fabian’s friend was saved by a man who threw himself on a grenade to protect those around him. The man knew only his savior’s nickname and the year he died, but volunteers were able to locate him.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard