U.S. Department of Defense

Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs)

News Release

IMMEDIATE RELEASE No. 0264-08

April 02, 2008

DoD Identifies Marine Casualty

The Department of Defense announced today the death of a Marine who was supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Major William G. Hall, 38 of Seattle, Washington, died March 30, 2008, from wounds he suffered while conducting combat operations in Al Anbar province, Iraq, on March 29. He was assigned to 3rd Low Altitude Air Defense Battalion, Marine Air Control Group 38, 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing, I Marine Expeditionary Force, Camp Pendleton, California.

April 2, 2008

Major William Gregory Hall, 38, was killed in action March 29, 2008 in Iraq.

Known to friends as “Billy,” he had deep roots in Skyway and King County, Washington. He went to Garfield High School and graduated from Washington State University before a long and distinguished Marine career that ended Saturday.

A Marine Corps representative says Hall was on patrol in Fallujah when his vehicle was hit by an improvised explosive device, or IED.

“He was very proud to be a Marine,” said Sharron McMullin, his cousin. “He ate, lived and breathed the Marine Corps; he was even excited about going to serve in Iraq.”

His family says the married father of four was on his third tour in Iraq.

“We’ve suffered a great loss, but we are so proud of him, we have a lot of fond memories, he really left a legacy,” McMullin said.

He enrolled in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps while studying at WSU and served in the Marines for 15 years.

He leaves behind a wife, two daughters and two stepsons. A public memorial service is planned for 11 a.m. April 5 at the Tabernacle Missionary Baptist Church, 2801 S. Jackson Street in Seattle, Washington.

The following week, Hall will be laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery.

Flowers and letters of condolences may be sent to: Mildred Hall, 10766 68th Avenue South, Seattle, Washington 98178.

2 April 2008:

A 38-year-old Marine major from Seattle has died in Iraq from wounds suffered during combat, the Defense Department says.

Major William G. Hall died Sunday from wounds suffered during combat in Anbar province on Saturday, the military said Wednesday.

He was assigned to the 3rd Low Altitude Air Defense Battalion, Marine Air Control Group 38, 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing, I Marine Expeditionary Force, Camp Pendleton, California.

A 1987 graduate of Seattle’s Garfield High School, Hall earned a bachelor’s degree in physical education from Washington State University in 1992. While at WSU, he enrolled in the Reserve Officers Training Corps and later joined the Marines.

In Iraq, Hall’s family said, he was training Iraqi troops to take over the duties of American soldiers. He didn’t try to downplay the danger he faced, but he also spoke of good things that were happening.

“I know most of what you hear on the news about Iraq is not usually good news and that so many are dying over here,” he wrote in a March 27 e-mail to his family, two days before he was wounded. “That is true to an extent but it does not paint the total picture and violence is not everywhere throughout the country.”

He ended his e-mail with: “Love you and miss you. I’ll write again soon.”

Before his unit deployed to Iraq in mid-February, Hall was selected for promotion to Lieutenant Colonel, said Major Jason Johnston, who is based at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar in San Diego, California. Though Hall’s unit was based at Camp Pendleton, it was attached to the Miramar air station, Johnston said.

April 3, 2008:

William G. Hall, 38, gave wise counsel to all

Major William G. Hall served in Iraq with the Marines.

Major William G. Hall had a wisdom, a maturity beyond his years that enabled him to provide sound counsel to his elders and, at the same time, guide those far younger than himself.

“He could be having a conversation with me and then my 10-year-old niece could walk in the room and he’d capture her like he’d just captured me,” said Major Hall’s eldest sister, Dolores Perry, 56, of Seattle. “He could talk to anyone — from the minister to a drug addict. He was just that kind of person.”

Major Hall, a 1987 graduate of Seattle’s Garfield High School, embodied a quiet strength and respect for tradition — both the traditions of the Marine Corps, where he moved up the ranks over the course of his 15-year career, and his family’s traditions. Like coming home at Christmas and calling his mother at Easter, which he did this past Easter Sunday.

It was 1 a.m. in Iraq, and his voice sounded tired, Perry said.

“He didn’t say a lot. He just gave us the reassurance he was OK,” she said.

It was their last conversation.

Major Hall — who was called “Billy” by those closest to him — was injured in Iraq’s Anbar province by an improvised explosive device on Saturday (March 29, 2008) and died the following day. He was 38.

Before his unit deployed to Iraq in mid-February, Major Hall was selected for promotion to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, said Major Jason Johnston, who is based at Marine Corps Airstation Miramar in San Diego. Though Major Hall’s unit — the 3rd Low Altitude Air Defense Battalion, Marine Air Control Group 38, 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing, I Marine Expeditionary Force — was based at Camp Pendleton, it was attached to the Miramar air station, Johnston said.

“We went through basics school together, and we were off and on in touch throughout our careers,” Johnston said. “I talked to him just before he left.”

Major Hall would have been promoted to his new rank sometime this year, Johnston said.

After graduating from high school, Major Hall earned a bachelor’s degree in physical education from Washington State University in 1992. While at WSU, he enrolled in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, later joining the Marines. He met his future wife while assigned to a base in Florida, and he later served in Georgia, California and Japan.

According to his family, this was Major Hall’s second deployment to Iraq, where he was training Iraqi troops to take over the duties of American soldiers. And while he didn’t try to downplay the danger he faced, Major Hall also spoke of the good things happening in the war-torn country.

“I know most of what you hear on the news about Iraq is not usually good news and that so many are dying over here,” Maj. Hall wrote in a March 27 e-mail to his family, two days before he was fatally wounded. “That is true to an extent but it does not paint the total picture, and violence is not everywhere throughout the country. So please don’t associate what you see on the news with all of Iraq.”

He ended his e-mail with: “Love you and miss you. I’ll write again soon.”

In addition to his sister, Major Hall is survived by his wife, Xiomara Hall; daughters Tatianna, 6, and Gladys, 3; stepsons Xavier, 13, and Xander, 9, all of Temecula, California; his mother, Mildred Hall, of Seattle; his sister Margie Bell, of Renton; his aunt, Alberta Hall, of Seattle; his uncle, Howard Berry of Kent; and several nieces and nephews.

The public is welcome to attend a memorial service for Major Hall that will include military honors at 11 a.m. Saturday at Seattle’s Tabernacle Missionary Baptist Church, 2801 S. Jackson St. A memorial service is also to be held Monday at Camp Pendleton, California.

Major Hall will be buried sometime next week at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Flowers and letters of condolence can be sent to Mildred Hall, 10766 68th Ave. S., Seattle, Washington 98178.

24 April 2008:

‘Warm, Gracious’ Marine Laid to Rest Fifteen-Year Veteran From Seattle Served In Iraq, Afghanistan

By Mark Berman

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Thursday, April 24, 2008

Marine Lieutenant Colonel William G. Hall was the kind of guy who always visited his family at Christmas and called his mother on Easter, even while serving thousands of miles away.

Hall, 38, of Seattle, died March 30, 2008, from wounds he suffered March 29 during combat in Iraq’s Anbar province.

“I can’t tell you how fine this young man was — the finest husband, father, son, Marine, individual — warm, gracious, just our very best,” Pat Ward, a longtime family friend, told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “My heart breaks.”

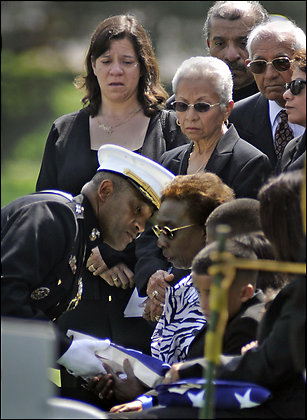

Yesterday, more than 150 mourners gathered at Arlington National Cemetery to say goodbye to Hall, who was posthumously promoted from major. The father of four was the 419th member of the military killed in Iraq or Afghanistan to be buried at Arlington. He had spent 15 years in the military.

Under a sunny, blue sky, mourners followed the horse-drawn caisson carrying Hall’s coffin down Marshall and Bradley drives, two of the roads that border Section 60, where many of the soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan are buried.

Folded flags were presented to his wife, Xiomara, and his mother, Millie. Hall is also survived by daughters Tatianna, 6, and Gladys, 3, and stepsons Xavier, 13, and Xander, 9.

He was assigned to the 3rd Low Altitude Air Defense Battalion, Marine Air Control Group 38, 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing, 1st Marine Expeditionary Force, based at Camp Pendleton, California.

“I know most of what you hear on the news about Iraq is not usually good news and that so many are dying over here,” Hall wrote in an e-mail to his family two days before he was wounded, according to the Seattle Times. “That is true to an extent but it does not paint the total picture and violence is not everywhere throughout the country.”

The e-mail ended: “Love you and miss you. I’ll write again soon.”

Hall earned a bachelor’s degree in physical education from Washington State University in 1992 and received his commission that December, officials said. In addition to Iraq, he served in Afghanistan, Japan, California and Georgia.

“He could be having a conversation with me, and then my 10-year-old niece could walk in the room and he’d capture her like he’d just captured me,” Hall’s eldest sister, Dolores Perry, told the Seattle Times. “He could talk to anyone — from the minister to a drug addict. He was just that kind of person.”

Perry, 56, said her brother called home Easter Sunday. It was 1 a.m. where Hall was, and he sounded tired, but “he just gave us the reassurance he was okay,” she said.

It was the last time they would talk.

26 April 2008:

Lieutenant Colonel Billy Hall, one of the most senior officers to be killed in the Iraq war, was laid to rest last week at Arlington National Cemetery. It’s hard to escape the conclusion that the Pentagon doesn’t want the public to know that.

The family of 38-year-old Hall, who leaves behind two young daughters and two stepsons, gave their permission for the media to cover his Arlington burial—a decision many grieving families make so that the nation will learn about their loved ones’ sacrifice. But the military had other ideas, and they arranged the Marine’s burial Wednesday so that no sound, and few images, would make it into the public domain.

Hall’s story is a moving reminder that the war in Iraq, forgotten by much of the nation, remains real and present for some. Among those unlikely to forget the war: 6-year-old Gladys and 3-year-old Tatianna. The rest of the nation, if it remembers Hall at all, will remember him as the 4,011th American service member to die in Iraq, give or take, and the 419th to be buried at Arlington. Gladys and Tatianna will remember him as Dad.

The two girls were there in Section 60 on Wednesday beside grave 8,672—or at least it appeared that they were from a distance. Journalists were held 50 yards from the service, separated from the mourning party by six or seven rows of graves and penned in by a yellow rope.

“We’re not going to be able to hear a thing,” a reporter argued.

“Mm-hmm,” an Arlington official answered.

The distance made it impossible to hear the words of Chaplain Ron Nordan, who, an official news release said, was leading the service. Whatever Nordan had to say about Hall’s valor and sacrifice was lost to the drone of airplanes leaving National Airport.

It had the feel of a throwback to Donald Rumsfeld’s Pentagon, when the military cracked down on photographs of flag-draped caskets returning home from the war.

On March 29, William Hall was riding from his quarters to the place in Fallujah where he was training Iraqi troops, when his vehicle hit an improvised explosive device. He was taken into surgery but died from his injuries. The Marines awarded him a posthumous promotion from Major to Lieutenant Colonel.

Newspapers in Seattle, where Hall had lived, printed an e-mail the fallen fighter had sent his family two days before his death.

“I am sure the first question in each of your minds is my safety, and I am happy to tell you that I’m safe and doing well,” he wrote, giving his family a hopeful picture of events in Iraq. “I know most of what you hear on the news about Iraq is not usually good news and that so many are dying over here,” the e-mail said. “That is true to an extent but it does not paint the total picture, and violence is not everywhere throughout the country. So please don’t associate what you see on the news with all of Iraq.

“Love you and miss you,” he wrote. “I’ll write again soon.”

Except that he didn’t. And on Wednesday, his family walked slowly behind the horse-drawn caisson to Section 60.

A media protest clouds Marine’s final journey

By ROBERT L. JAMIESON Jr.

SEATTLE P-I COLUMNIST

30 April 2008

In life, Lieutenant Colonel William G. Hall of Seattle didn’t always care for the way events in Iraq were spun.

The same might be said about last week’s coverage of his burial. It should never have become controversial.

Hall, 38, who was killed when a bomb went off March 29, 2008, in Fallujah, was laid to rest April 23, 2008, at Arlington National Cemetery. Reporters covered this last goodbye. But an influential writer for The Washington Post accused the government of arranging the Marine’s burial “so that no sound, and few images, would make it into the public domain.”

The columnist said that he and fellow journalists were kept 50 yards from the service, separated by rows of graves. Reporters were quoted complaining about camera angles or being unable to hear the service.

Add it up, The Post said, and “it’s hard to escape the conclusion that the Pentagon doesn’t want you to know” — about the tears, about the human costs of war. It’s a refrain you’ll hear at most Seattle peace protests.

It also sounded four years ago, when the Pentagon cracked down on publicizing images of soldiers’ homecomings in caskets. The issue raged after a military contractor from the Seattle area took photos of flag-draped coffins loaded into a plane.

Cynics believe that the government controls public attitudes by pushing negative photos or news from view, and there may be a kernel of truth there. But that doesn’t seem to describe Hall’s Arlington farewell.

He was one of the military’s best, one of the highest-ranking Marines killed in Iraq. The humble, married father of four also was a role model for youths. He always let those here at home know that even though bad things were happening in Iraq, the troops did good things that weren’t getting attention.

The military would be proud to tell his story.

If some suspect a conspiracy to keep his funeral out of the news, Hall’s family does not — and what the family thinks is what ought to matter most here.

“My brother’s wife spoke with cemetery officials and told them what she wanted for the funeral,” Dolores Perry, Hall’s older sister, told me this week from her Renton home.

“She did not mind media being there.”

After the request, military officials forged a balance, allowing reporters to cover the story while giving the family room to grieve.

But just before Hall’s funeral, the media staging area was moved slightly to a less desirable area for journalists because of bad sight lines.

The decision even caught Arlington’s public affairs chief, Gina Gray, by surprise. She told me the sudden shift came from Arlington’s deputy director, a civilian government employee who vaguely cited “rules” for his decision.

But there are no rules specifically outlining the handling of media during services, Gray said. That suggests that the deputy director — not some Pentagon heavy — made the decision that has fired up journalists during the past week.

The Pentagon was miffed that it ended up getting blamed.

But what bothers me is the way the somber ceremony to honor a man who died for his country got manipulated by the media to create outrage.

After all, Perry told me that her brother’s wife “was satisfied” with how the funeral turned out.

So was Hall’s mother, Mildred, who received a folded American flag at the ceremony.

So, too, was Perry, who was touched to see her brother receive a rifle-volley salute.

“The media did a good job from where they were,” Perry said. “We were able to hug and cry without cameras being down our throats. We could all say goodbye to Billy. …”

She said the family barely noticed the media. She called the ceremony, “beautiful — more than I could have imagined.”

Beautiful for everyone — except those using a Marine’s funeral to attack the government or spin conspiracies.

There’s one benefit here: Singed by the firestorm, the military said Wednesday that it would work to give better access to reporters with permission from families to cover funerals at Arlington.

That way the public gets a better view, too.

In life, Hall was known for having a knack for making a tough situation better. In death, he’s still accomplishing that mission.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard