From a contemporary press report: 17 August 2001

Private First Class Gallagher comes home:

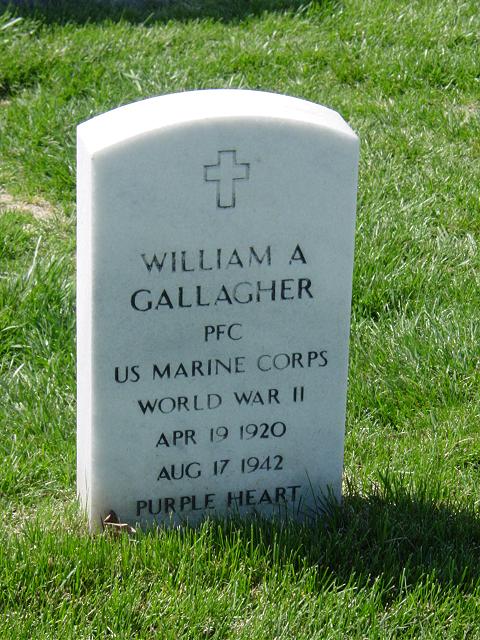

Six decades after he died on a Pacific atoll, a Wyandotte Marine will be buried today in Arlington Cemetery August 17, 2001.

In the waning days of August 1942, a dark coupe wound through Wyandotte and pulled up to the Gallagher home. Angeline Gallagher watched the driver emerge and approach her with a telegram.

She sent him away before reading: “Deeply regret to inform you that your son Private First Class William Albert Gallagher US Marine Corps Reserve was killed in action … Present situation necessitates interment temporarily in the locality where death occurred and you will be notified accordingly.”

She dropped the telegram and screamed. Her only son was dead.

Last November came another visit. Angeline’s daughter, Emma Schmitt, stood at her door in Roseville as a Marine sergeant and two forensics experts approached. This time their news brought resolution.

The Pentagon had identified Bill Gallagher as one of 19 Marines whose remains were recovered on Makin Atoll in the South Pacific. Though the U.S. government knew the men died during an August 17, 1942, raid on the

Japanese-occupied island, their burial site was unknown.

Today, exactly 59 years after they fell, the Marines will receive a heroes’ welcome home. Thirteen of the 19 — including Private Gallagher — are to be buried with fanfare this morning at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. The rest have been buried in their hometowns.

“We finally got the whole story,” said Schmitt, the only surviving member of Gallagher’s immediate family. She plans to be at Arlington today. “It’s like pieces of the puzzle are finally in there.”

A Marine’s quest

Schmitt, 76, said that if her brother were alive today, he would be fascinated by how the pieces came together. The persistence of families and ex-Marines sparked the recovery of the remains, and the savvy of forensics and DNA

experts established their identity and circumstances of death.

None of it might have happened without Ben Carson, a Marine who survived the raid and was determined to bring his fallen comrades home.

Carson, 78, who now lives in Hillsboro, Oregon, recalled the day 221 members of the 2nd Raider Battalion launched a chaotic submarine raid. The unit killed 83 Japanese before its leader, Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson, ordered a

withdrawal. Crippled by heavy surf, faulty equipment, wounded men, enemy fire and lack of communication, Carlson’s Raiders left the dead behind after

arranging for their burial.

“These people were interred on foreign soil. That’s not the way America handles its heroes,” said Carson, who plans to attend today’s burial.

The government sent officials to Makin Atoll twice, in 1948 and 1998, but failed to find the remains. It wasn’t until late 1999, after a letter-writing campaign

headed by Carson, that they returned and were led to a mass grave by a native who had helped bury the soldiers in 1942.

The remains were transported to Hawaii, where experts spent the next year cataloging each item and identifying the men. They asked every soldier’s next of kin, including Emma Schmitt, to provide DNA samples.

Gallagher was identified through DNA, the gap between his front teeth and a

small indentation on his forehead where he’d been hit by a large stone hurled by a neighborhood boy years before.

Experts also established how Gallagher was killed. His right forearm, sternum and clavicle were shattered or missing, meaning he likely was shot while holding a rifle to his chest. The bullet went clean through his body, killing him instantly.

Carson said Gallagher was the unit’s radio man and probably was spotted and shot because of his aerial. He was 22 when he died.

‘A source to look up to’

The new information about Gallagher’s death might have been little comfort to his family in 1942. His parents had already lost one son to a train accident, and

Gallagher was the only remaining boy among their four children.

Angeline Gallagher’s hair turned white within two weeks of the telegram’s arrival, Schmitt said.

When Joseph Gallagher heard of his son’s death, he began methodically smashing printing plates at the Detroit Times, where he worked.

Schmitt said the tragedy of her brother’s death didn’t hit her until she saw his friends return from the war. “My head knew he was dead, but my heart didn’t,” she said.

The death devastated Gallagher’s closest friend, John Haggarty, who had known the Marine since they were students at Roosevelt High School in Wyandotte. As kids they would swim at a local quarry and hang out at a confectionary store called McGrath’s.

“Bill had a yearning to join the military,” said Haggarty, 80, who now lives in Ohio. “I think he was a fellow that looked for a cause, something big in life. I think he found it in the military.”

Left with a telegram but no body, the Irish-Catholic Gallagher family held a funeral mass using a log in place of his body.

Gallagher’s sister Eleanor, to whom he wrote often from his California base and overseas, bestowed her own honor. When she and her husband tried unsuccessfully to conceive, Gallagher had written that she must never give up. Eleven months after his death, Eleanor delivered a boy and named him William.

“I grew up in his shadow because his sisters would always talk about him,” said Gallagher’s namesake, Bill Giesin, whose mother died in 1960. “He was always a source to look up to.”

Giesin, 58, spent years researching his uncle’s life and the Makin raid. In 1990, he wrote an open letter to the Marine magazine Leatherneck asking for information about Gallagher.

He received responses from several surviving Makin raiders, including Carson. Carson detailed what he knew about Gallagher’s death and recalled that Gallagher had once saved him from drowning during training.

“It was a beautiful letter,” Giesin said. “I was so touched by it I sat on the couch and cried.”

Giesin met with Carson and the two wondered aloud whether Gallagher might ever be returned and buried at Arlington.

‘Now Billy can rest’

In addition to the national ceremony, Gallagher will be honored locally by members of the Wyandotte Marine Corps League.

At 6 tonight, the league will salute Gallagher with the presentation of colors, bagpipes, a rendition of “Taps” and speeches about the raid and the hometown hero who died in it. The ceremony will take place at the league’s headquarters, 1323 Eureka in Wyandotte.

League member Norm Sieloff, who interviewed Gallagher’s family for a speech about him, said the group also will dedicate a wall of its renovated wing to Gallagher in October and establish a memorial fund in his name to help local charities.

Schmitt said she is amazed her brother has garnered so much attention 59 years after his death. At first she was content to let him lie where he was found, recalling that he had once returned from their uncle’s funeral disgusted

over the public display of grief he saw there.

At dinner after the funeral, Schmitt said, Gallagher pounded the table and said, “I pray to God that when I die, it’s halfway around the world where there’s no one to slobber over me!”

Although he got his wish, Schmitt said she realized it’s time to finally bring him home and give him a proper burial.

“I figure now Billy can rest, and so can the rest of us.”

Click Here For More Information

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard