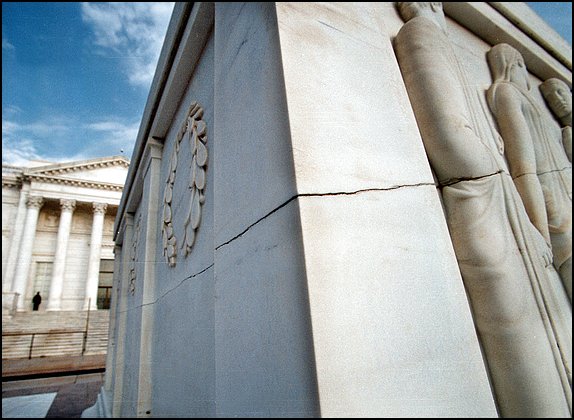

A dark crack meanders along all four marble sides of the Tomb of the Unknowns, one of the country’s most hallowed war memorials, and the soldiers who spend their lives guarding the tomb say the fault line is growing.

Sergeant Paul Basso of the Army’s 3rd U.S. Infantry “Old Guard” Regiment stood on a temporary platform erected for this weekend’s Memorial Day ceremonies at Arlington National Cemetery one recent morning to point out the unsightly fissure splitting the expanse of white marble, glinting in the sun.

“See?” Basso said. “It’s worsening.”

Cemetery officials say the crack — which has long been creeping across the 71-year-old monument — now takes more than a 360-degree course around the facade and has gotten so bad that they have decided the entire memorial must be replaced, a process expected to take about a year.

Arlington Superintendent John C. Metzler Jr. said last week that cemetery officials decided to replace the stone after concluding that a 1989 cosmetic repair job — which cemetery historian Thomas Sherlock compared to fixing a bathtub with tile grout — had done nothing to conceal the problem and may have exacerbated it.

“Because the tomb itself has cracked . . . I’m concerned that it will have an effect on the integrity of the tomb itself, as well as its decorative finishes,” Metzler said. Metzler detailed the problem in August 2001 in a request for funds to the Department of Veterans Affairs, which gave the go-ahead for the project last year.

Metzler said he did not know yet how much the project will cost. John Haines, a retired automobile dealer from Glenwood Springs, Colo., has donated the $31,000 price of the marble. Rex E. Loesby, the president of Sierra Minerals Corp., which operates the quarry excavating the marble, estimated the cost of finishing and carving the stone at an additional $500,000 to $1 million.

The memorial, which is known both as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and the Tomb of the Unknowns (it has never been officially named), has sat atop a hill in Arlington National Cemetery with sweeping vistas of the Washington skyline since 1921, when an unidentified soldier from World War I was interred there. The enormous rectangular marker atop that soldier’s crypt, made from a 55-ton block of white marble from the Colorado Yule Quarry, was dedicated in 1932.

Sculptor Thomas Hudson Jones carved the memorial with mourning wreaths, three figures representing Peace, Victory and Valor, and the inscription, “Here Rests in Honored Glory An American Soldier Known But to God,” now split by the unsightly crack.

Remains of three other unknowns, from World War II, Korea and Vietnam, were interred there over the years, but the one from the Vietnam War was disinterred in 1998 after DNA testing requested by the family of Air Force First Lieutenant Michael J. Blassie identified the remains as his.

The solemn changing of the guard ceremony by the tomb’s sentinels, members of the Old Guard regiment in immaculate battle dress uniforms who guard the tomb in 24-hour shifts, has long been a quietly moving experience for many of the 4 million people who visit the cemetery yearly.

Sherlock, the cemetery historian, said that the appearance of the crack was first documented in the 1940s, in pictures of President Harry S. Truman placing a wreath on the tomb on Memorial Day.

Over the years, the entire surface of the marble has lost 1.46 millimeters to erosion, according to the cemetery. At one point, the crack sprouted green and black algae.

“At this rate significant loss and erosion of the stone can be expected within the next 20 years. This deterioration will result in an effect on the visitors’ experience to this national shrine,” a cemetery study concluded in December 2001. The possibility that the memorial will crack clean through and slide apart is “remote,” the report said.

Loesby said he thinks that the crack started when mine workers from the Colorado Yule Marble Co. in central Colorado accidentally “shocked” the white slab of marble when they removed it from the quarry in 1931. The quarry was later shut down for decades. It was reopened, then failed and was reopened again by Loesby in 1999.

Now the lengthy search for the right replacement block of marble has begun. Loesby has employees feverishly mining the area in the quarry where the original slab was found in hopes of finding a suitably white replacement stone.

Loesby hopes to have the right stone cut out of the quarry and transported down the mountain to a celebration in the tiny nearby town of Marble by Labor Day.

Metzler won’t put such a timeframe on the project, saying the clock won’t begin ticking until the right piece of marble is found. After that, Metzler said, it could take about a year before the new tomb is installed. The tomb will be closed to the public for about two weeks while the renovations are going on, he said.

Basso and the others who guard the tomb spend hours shining their shoes, polishing buttons and rehearsing their somber rituals. And they can recite the tomb’s flaws by heart, like wrinkles on the face of a loved one. There’s the chipped leaf on the north side, the tomb guards say, and the letters “r” and “e” run together in the inscription.

When the right stone is found and approved by the cemetery, its surface will have to be smoothed and finished by a master stone carver, either in Colorado or on the East Coast. Then the carver will have to copy the original design — by architect Lorimer Rich — as closely as possible, even copying the cherished imperfections.

“We think it’s a beautiful design and a historic design,” historian Sherlock said. “It’s been here for many, many years . . . so we want as close as humanly possible to replicate it.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard