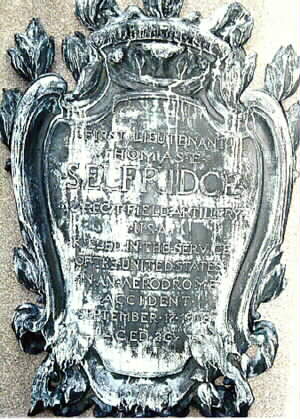

He became the first military air casualty when a plane in which he was a passenger, and which was piloted by Orville Wright, crashed during Army performance tests at Fort Myer, Virginia, on September 17, 1908.

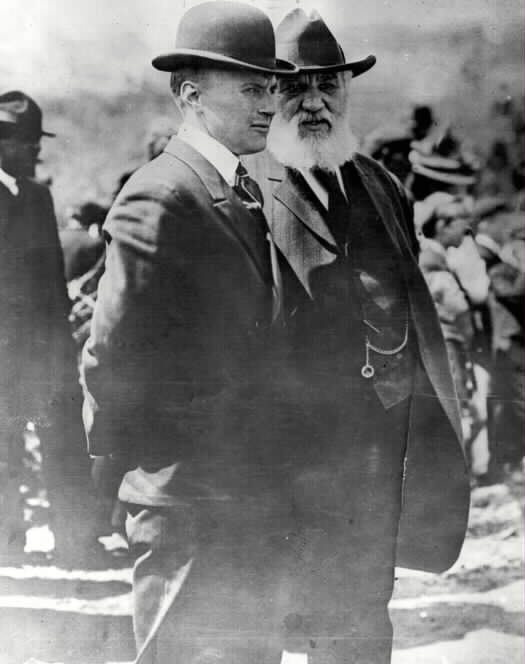

Selfridge was an early Army aviator and had already flown solo in the “White Wing,” the airplane designed and built by the inventor of the telephone, Alexander Graham Bell and his AEA organization.

On the day of the accident, flying at about 150 feet from the ground over Fort Myer, Wright put the plane into a steep turn. The wing flexed, and the propeller blade snapped off and the plane, out of control, crashed. Selfridge died that afternoon, the first man killed in a heavier-than-air flying machine. Orville Wright was hospitalized for several weeks.

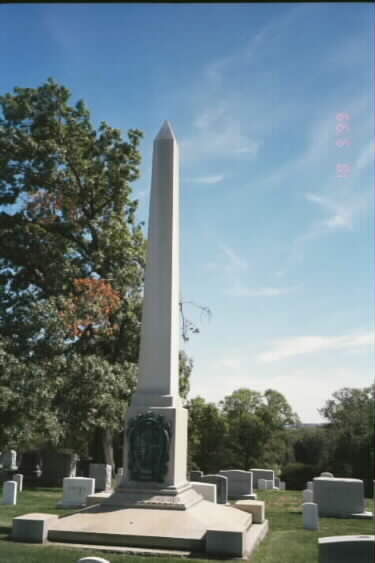

Selfridge is buried in Section 3 of Arlington National Cemetery, near the very spot that he fell to his death.

See biographical information on Colonel Charles deForest Chandler for more information on early Army aviation.

His brother, Edward A. Selfridge, Jr., Captain, United States Army, is also buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

T. E. Selfridge & Alexander Graham Bell

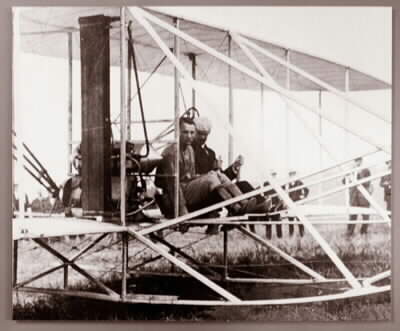

Thomas E. Selfreidge & Orville Wright At Fort Myer, Virginia

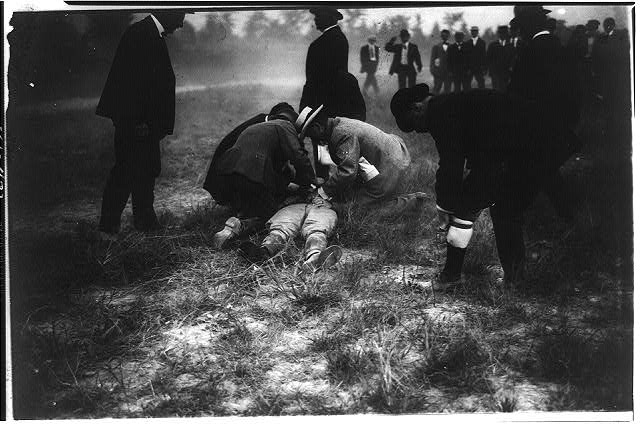

Thomas E. Selfridge Plane Immediately Following The Crash

Plane Crash Which Took The Life of T. E. Selfridge

Doctors Attending to Lieutenant Selfridge Following The Crash On Fort Myer

Thomas E. Seldridge Being Removed From The Scene of the Crash

Library of Congress Photos

Lieutenant Selfridge just before takeoff (Army photo)

Bystanders try to extricate the mortally wounded Lt. Thomas Selfridge from the wreck of the Wright Flyer immediately after its 1908 crash at Fort Myer. At far right, several men attend to the injuries of Orville Wright, who is lying on the ground at their feet. (Army photo)

Courtesy of the National Aviation Hall of Fame

Born in San Francisco in 1882, he was appointed to the Military Academy at West Point and graduated with the class of 1903. Early in his military career he became intensely interested in aeronautics. He read about Dr. Alexander Graham Bell who was building kites with great lifting capacity at his summer home near Baddeck, Nova Scotia. He wrote Dr. Bell asking permission to witness some of the experiments. Bell was so impressed with him that President Theodore Roosevelt assigned him to Baddeck as an official observer. Here, in the summer of 1907, he met F.W. “Casey” Baldwin, J. A. D, McCurdy and Glenn Hammond Curtiss. The team brought together by Dr. Bell discussed many ideas about the future of powered flight. Mrs. Bell suggested that more progress could be made by forming an association and she even offered to finance the group. The Aerial Experiment Association was formed in October, 1907 and he was elected Secretary. The Association built a large kite called “Cygnet I”. It had several thousand tetrahedral cells and a wing span of over 42 feet. On December 6, as he lay prone in the center of the kite placed aboard a scow, it was towed by a tugboat across lake Bras d’Or. When a strong wind arose, the kite left the scow and soared to a height of 168 feet. For seven minutes he remained aloft making scientific readings until the wind dropped and the kite settled to the water. This was his first flight.

In early 1908 he was accorded the honor of designing the Association’s first airplane. It was called the “Red Wing” because of its red silk covered wings. Next, they built the “White Wing”, incorporating hinged ailerons, in which he made a successful flight becoming the first Army officer to make an airplane flight in America. Their third airplane, the “June Bug”, won the Scientific American Trophy for a flight of over 1 Kilometer. The Association offered the first airplanes for sale in America for $5,000 each with delivery in sixty days. Their fourth airplane, the “Silver Dart”, became the first airplane to be flown in Canada.

In August 1908, he was assigned to an official Board responsible for tests of the Army Signal Corps’ first dirigible at Fort Myer, Virginia. He made numerous flights in this dirigible before it was officially accepted. He was next assigned to a board conducting the first trials of the Wright airplane to see if it could fly 40 miles an hour, carry two persons aloft, and be portable enough to be transported by a mule-drawn wagon. When Orville Wright made the first flight at Fort Myer, the crowd gasped in astonishment. For the next two weeks, record after record was broken as the airplane proved its capabilities. On September 17 he climbed into the passenger seat to fly with Orville. They were in a slow turn during the fourth round when he heard a tapping sound. Then came two big thumps. The airplane shook violently, making a sudden turn to the right. The engine was shut off. The plane nosed straight downward, headed for the ground. In an almost inaudible voice he exclaimed “Oh! Oh!” as he hung desperately to the wing struts. When the plane was about twenty-five feet from the ground it began to level out. A few more feet and it would have landed safely. Instead there was a terrifying sound of splintered wood. For a moment there was silence as a noiseless cloud of dust rose around the wreckage. Then a chorus of human voices gasped, and there was the trampling of running feet as a human wave rushed toward the wreckage. Men raised the crumpled plane and found him pinned beneath the engine. He had made the first supreme sacrifice in conquering the problems of powered flight. He was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery and later an Air Force Base at Mount Clemens, Michigan was named in his honor. His sudden death was a great loss to aeronautics. He served with the fledgling Air Corps at a time when its wings were beginning to take definite form. Endowed with the enthusiasm of youth and a keen mind, he entered his chosen field with a deep scientific interest and a special love for the great challenges of life.

The Chief Signal Officer, U. S. Army

Sir: I have the honor to submit the following detailed report of the accident to the Wright Aeroplane at Ft. Myer, Virginia, on September 17, 1908.

The Aeronautical Board of the Signal Corps. composed of Major C. McK Saltzman, S. C., Captain Chas. S. Wallace. S. C. and Lieutenant Frank P. Lahm, S. C. assisted by Lieut. Sweet of the Navy, and Lieut. Creecy, of the Marine Corps, also Mr. Octave Chanute and Professor Albert Zahm, made a thorough examination on the morning of September 18th, the day after the accident, of the aeroplane and the ground, and carefully examined witnesses of the accident. The following is their report:

“That the accident which occurred in an unofficial flight made at Ft. Myer, VA at about 5:18 p.m., on September 17, 1908, was due to the accidental breaking of a propeller blade and a consequent unavoidable loss of control which resulted in the machine falling to the ground from a height of about seventy-five (75) feet.

The Board finds that First Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge, First Field Artillery, (attached to the Signal Corps of War Department orders and assigned to aeronautical duty), accompanied Mr. Wright, by authority, on the aeroplane, for the purpose of officially receiving instruction and received injuries by the falling of the machine which resulted in his death.”

The detailed examination of witnesses referred to in the above paragraph is given herewith.

Sergeant Daley, Battery “D”, 3d Field Artillery, was on the artillery guard house porch at the time of the accident and testified that he saw the rear rudder collapse and fall to the front and to the right, then after the machine had advanced about 60 feet, the broken propeller blade fell to the ground. Sergeant Daley gave the impression of being a reliable witness.

Private Allen, Troop “F”, 13th Cavalry, was the mounted sentinel stationed in front of the lower cemetery gate. He was about 30 yards from where the aeroplane struck the ground. He testified that he heard a loud noise, saw the propeller blade fly, and saw the machine start down, then saw it drop rapidly head first. While the machine was falling, he was occupied trying to get out of the way with his horse. He said the men in the machine tried to talk while falling; that when he went up to the machine after it was on the ground, Mr. Wright’s head was hanging between two wires which crossed on his chest. His right arm was extended under Lieut. Selfridge as though to hold him up. He exclaimed, “Oh, my arm.” He said that the front ends of the skids struck the ground first.

Corporal Forrester, Battery “D”m 3d Field Artillery, was the non-commissioned officer of the guard on duty around the field. He was mounted and was just in the rear of the aeroplane shed. He heard the propeller snap, then saw nothing until the machine was on the ground. Corporal Forrester and Private Allen demonstrated to the Board the position in which Lieut. Selfridge and Mr. Wright were found.

Mr. Chanute was 15 feet south of the press tent and 560 feet west of the point where the machine struck, that is on the opposite side of the aeroplane shed. Mr. Chanute testified that the machine was perhaps 60 feet up and circling the field to the left. He went 40 or 50 feet to the south so as not to be behind the tents between himself and the aeroplane shed. When the machine was 300 feet from him, the propeller flaked off or snapped, and the piece fluttered down to the ground; the aeroplane maintained it’s level at 60 or 100 feet, then oscillated and pitched down with the left side depressed and disappeared from his view behind the bushes. He did not see it strike. When he examined the broken propeller blade, Mr. Chanute testified that the wood was brittle and over seasoned, or kiln dried. A few days later Mr. Chanute informed me that he thought the propeller blade had struck the upper guy wire of the rear rudder and had torn the end of the wire from it’s attachment from the rudder.

Dr. George A. Spratt, of Dayton, Ohio, a friend of Mr. Wright’s, was at the upper end of the field near the starting point at the time of the accident. His written statement of his observations of the accident is attached hereto marked “A”.

Sergeant Sweeney, post ordinance sergeant at Ft. Meyer, was at the battery guard house at the time of the accident. Mr. Charles Tayler, a mechanician employed by Mr. Wright, was also examined. Their testimony was not particularly pertinent.

On October 31, 1908, I talked with Mr. Wright at the hospital at Ft. Meyer, and learned from him the following facts:

He said he heard a clicking behind him about the time he crossed the aeroplane shed. He decided to land at once but as there was scarcely time to do it before reaching the cemetery wall, he decided to complete the turn and head toward the upper end of the field. He thought he was about 100 feet high at the time the propeller broke and that he descended more or less gradually to 40 feet, then the machine dropped vertically. He shut off the engine almost as soon as the clicking began, then corrected a tendency to turn which the machine seemed to have. All this time the machine was coming down pretty rapidly. He pulled the lever governing the front rudder as hard as possible, but the machine still tipped down in front, so pushed the lever forward and pulled it back again hard, thinking it might have caught or stuck. At the time of our conversation, October 31st. he said he thought that the rear rudder had fallen sideways and the upper pressure of the air on it probably threw the rear of the machine up and the front down, and that this accounted for the failure to respond more readily to the front rudder. He stated that at a height of about 60 feet, the front end of the machine turned nearly straight down and then it fell. About 15 feet from the ground it again seemed to respond to the front rudder and the front end came up somewhat, so that it struck the ground at an angle of about 45 degrees.

The following is a list of witnesses in addition to those whose testimony is given above.

Mr. Magoon, Superintendent of Arlington Cemetery, was half way between the two gates of the cemetery and just inside the wall.

The following reporters were at the balloon tent: Mr. Heis of the New York World, Mr. Dugan, of the United Press, Mr. Smith, of the Baltimore Sun, Mr. McMahan, of the Washington Herald

The following witnesses were near the new artillery stable, west of the point where the accident occurred: Mr. Robert F. Crowley, Arlington, Va. Mr. H. C. Ball, Clarendon, Va. Mr. E. E. Speer, Ballston, Va.

I examined most of the witnesses whose testimony is given above, immediately after the accident, on the field I was present when the Aeronautical Board made it’s examination the following day, September 18th, and talked at various times with Mr. Wright, Mr. Chanute, Professor Zalm, and others relative to the accident. At the time of the accident I was holding my horse and watching the machine from the upper end of the field near the starting point. When the machine struck, I galloped at once to the spot.

On September 17th, Mr. Wright was almost ready to begin his official trials so he put on a set of new and longer propellers that day for the purpose of tuning up the speed of his machine preparatory of making his official speed trial. These propellers were probably 9 feet in diameter, the ones in use up to that time were probably 8 feet 8 inches in diameter.

Lt. Selfridge was to leave for Saint Joseph, Missiouri, for duty in connection with dirigible No. 1, on September 19th and was very anxious to make a flight before leaving, so Mr. Wright, at my suggestion, had said a few days before that that he would take him up at the first opportunity.. On September 15th and 16th, high winds prevented him from making a flight. On September 17th, the instruments at the aeroplane shed recorded a northeast wind of four miles an hour. At 4:46 p.m., the aeroplane was taken from the shed, moved to the upper end of the field and set on the starting track. Mr. Wright and Lieut. Selfridge took their places in the machine, and it started at 5:14, circling the field to the left as usual. It had been in the air four minutes and 18 seconds, had circles the field 4 1/2 times and had just crossed the aeroplane shed at the lower end of the field when I heard a report then saw a section of the propeller blade flutter to the ground. I judge the machine at the time was at a height of about 150 feet. It appeared to glide down for perhaps 75 feet, advancing in the meantime about 200 feet. At this point it seemed to me to stop, turn so as to head up the field towards the hospital, rock like a ship in rough water, the drop straight to the ground the remaining 75 feet. I had measurements taken and located the position where the machine struck, 304 feet from the lower cemetery gate and 462 from the northeast corner of the aeroplane shed. The pieces of propeller blade was picked up at a point 200 feet west of where the airplane struck. It was 2 1/2 feet long, was a part of the right propeller, and from the marks on it had apparently come in contact with the upper guywire running to the rear rudder. This wire, when examined afterward, had marks of aluminum paint on it such as covered the propeller. The left propeller had a large dent, and the broken piece of the right propeller had a smaller dent indicating that the broken piece flew across and struck the other propeller. The upper right had guy wire of the rear rudder was torn out of the metal eye which connected it to the rear rudder. I am of the opinion that due to excessive vibration in the machine, this guy wire and the right hand propeller came in contact. The clicking which Mr. Wright referred to be being due to the propeller blade striking the wire lightly several times, then the vibrations increasing, it struck it hard enough to pull it out of it’s socket and at the same time to break the propeller. The rear rudder then fell to the side and the air striking this from beneath, as the machine started to glide down, gave an upward tendency to the rear of the machine, which increased until the equilibrium was entirely lost. Then the aeroplane pitched forward and fell straight down, the left wings striking before the right. It landed on the front end of the skids, and they, as well as the front rudder was crushed. Both Mr. Wright and Lieut. Selfridge were on their seats when the machine struck the ground, held there by wire braces which cross immediately in front of the two seats. It is probable that their feet struck the ground first, and as the machine dropped nearly head first, they were supported by these wire braces across their bodies. When I reached the machine, the mounted sentinels at the lower end of the field were entering at the left hand between the two main surfaces, which were now standing on their front edges. I found Mr. Wright lying across the wires mentioned above, trying to raise himself, but unable to do so. He was conscious and able to speak, but appeared very badly dazed. He was cut about the head where he had struck the wires, and possibly the ground. Lieut. Selfridge was lying stretched out on the wires, face downward, with his head supported by one of these wires. He died at 8:10 that evening of a fracture of the skull over the eye, which was undoubtedly caused by his head striking one of the wooden supports or possibly one of the wires. He was not conscious at any time. With the assistance of a couple of enlisted men I removed Mr. Wright from the machine and placed him on the ground, where he was immediately taken charge of by Army surgeons, among them Major Ireland, who were among the spectators at the time of the accident. Lieut. Selfridge was carried out immediately afterward and similarly cared for. At least two civilian surgeons among the spectators, whose names are not known, assisted in caring for both of them. Within ten minutes they were carried to the post hospital on litters by hospital corps men and were placed on the operating table. Captain Bailey, Medical Corps, USA Army, was in charge of the hospital at the time. He was assisted in the operating room by the surgeons mentioned above. In the meantime, the mounted sentinels had been placed around the aeroplane to keep back the crowd, a very difficult matter at that time. Mr. Wright was found to have two or three ribs broken, a cut over the eye, also on the lip, and the left thigh broken between the hip and the knee. He was in the hospital at Ft. Meyer for six weeks under the care of Major Francis A. Winter and at the end of that time went to his home at Dayton, Ohio. Lieut. Selfridge was buried with full military honors at Arlington cemetery on September 25th.

The wings on the right side of the machine were not badly damaged, those on the left side which struck the ground first were crushed and broken. Apparently the front rudder, skids, and left wings received most of the force of the fall. The rear rudder as shown on the accompanying photographs, exhibits “C”, “D” and “E” was thrown down on the rear end to the skids and on to the main body of the machine probably due to the shock on striking the ground. The gasoline tank was damaged sufficiently to allow the gasoline to leak out. The water cooler of the engine was somewhat twisted; the engine itself was not badly damaged, and could probably very easily be put into running order again. I had the aeroplane taken to pieces and removed to the aeroplane shed the evening of the accident. It was afterward shipped to Dayton, Ohio, by Mr. Wright’s direction.

Very Respectfully, (Signed) Frank P. Lalm 1st Lieut. Signal Corps

Appendix No. 1 PROCEEDINGS OF THE AERONAUTICAL BOARD OF THE SIGNAL CORPS WHICH CONVENED AT FORT MEYER AT 10:15 A.M, ON SEPTEMBER 18, 1908, FOR THE PURPOSE OF INVESTIGATING AND REPORTING ON THE CAUSE OF THE ACCIDENT TO THE WRIGHT AEROPLANE WHICH RESULTED IN THE DEATH OF FIRST LIEUTENANT THOMAS E. SELFRIDGE, FIRST FIELD ARTILLERY.

Present: Major C. McK. Saltzman, Captain Charles S. Wallace and Lieutenant F.P. Lahm Absent: Major George O. Squier and Lieutenant Benjamin D. Foulois.

There were also present Lieutenant George C. Sweet, U.S.N., and Lieutenant Richard B. Creecy, U.S.M.C., Officers officially detailed for the purpose of reporting and observing and reporting upon aeronautical work of the signal corps.

With the exception of Lieutenant Foulois, all members of the Board and Lieutenants Sweet and Creecy were present at the time of the accident.

The Board visited the scene of the accident, questioned witnesses very carefully and examined the machine.

Mr. Octave Chanute and Professor Albert F. Zahm were present by courtesy during the entire investigation and were consulted by the Board.

Mr. Wright’s condition was such as to prohibit the Board consulting or questioning him relative to the accident.

After due deliberation, from the evidence obtainable from all available sources, the Board finds—

That the accident which occurred in an unofficial flight made at Fort Myer, Va., at about 5:18 pm, on September 17, 1908, was due to the accidental breaking of a propeller blade and a consequent unavoidable loss of control which resulted in the machine falling to the ground from a height of about seventy-five (75) feet.

The Board finds that First Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge, First Field Artillery, ( attached to the Signal Corps by War Department orders and assigned to aeronautical duty), accompanied Mr. Wright, by authority, on the aeroplane, for the purpose of officially receiving instruction, and received injuries by the falling of the machine which resulted in his death.

A:

Gentlemen: The machine was completing the last quarter of the turn when the portion of the blade was thrown off. It was apparently the blade toward the center of the circle being described by the course of the machine, that was broken. The machine completed the circle and was headed toward the starting derrick, the engine running and the flight apparently undisturbed. It proceed about 200 feet and started to descend assuming a negative angle (i.e. the chord of the surfaces became directed toward the earth).

Its elevation was probably 65 feet when the descent began. AT about 25 feet above the ground its angle of incidence became positive (i.e. the chord of the surfaces directed skyward). It did not gain sufficient horizontal velocity by the downward and forward pitch for support. It again took a negative angle of incidence and struck the ground. The forward framing struck first the side to the left of the aviators slightly in advance of the side to the right. The angle at which the surfaces struck seemed to be about 40 degrees.

The stability of the machine considered sideways was disturbed and unsteady. The motor was topped during the first pitch forward.

The course of the descent may be shown diagrammatically, as it appeared to me, by the following dotted lines. The accompanying straight lines show the angle of incidence at the point in the course at which they are placed. The cross indicates the point of accident to the propeller.

In the early days of aviation, even a small plane crash was big news for The Washington Post — especially when it happened here and involved one of the Wright brothers. An excerpt from The Post of September 18, 1908:

Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge, of the signal corps, was killed, and Orville Wright, the aviator, received a fractured thigh and two broken ribs, late yesterday afternoon, when the lather’s aeroplane plunged to earth during an experimental flight over the drill grounds at Fort Myer. Lieutenant Selfridge, who had been taken aloft at his own request, died last night at 8:10 o’clock in the post hospital. Mr. Wright’s condition is not considered critical.

The accident was witnessed by a throng of upwards of 2,500 persons, who were instantly changed from cheering enthusiasts to saddened and depressed sympathizers.

The accident was caused by the breaking of one of the propeller blades. It occurred as the machine was making the second turn, at the lower end of the field, on the fourth lap.

An end of the blade flew off, and Mr. Wright apparently completely lost control of the machine, which tacked about choppily for a hundred feet or more, soared ten feet higher, and then dropped to the ground with a frightful force, from a height of about 75 feet.

The machine crumpled up into a tangled mass of wreckage, burying the two men. The horrified spectators dashed down the field, and those in the van lifted the machine and extricated the victims. Mr. Wright was conscious. Lieutenant Selfridge was unconscious, and his face was covered with blood, which gushed from a great gash on his forehead.

It seems to be the general opinion of the experts who have investigated the accident that when the machine hit the ground, both Mr. Wright and Lieutenant Selfridge landed on their feet first, and that they were thrown upward and outward by the tremendous force, landing on their heads.

A boy who witnessed the accident from the stone fence which bounds Arlington cemetery, said that they struck in this position.

“They were thrown in the air,” he said, “and then fell forward on their faces.”

Both men were removed in a few minutes to the finely equipped post hospital, where they were attended by a corps of army surgeons who happened to be present to witness the flight. Mr. Wright’s condition was early reported to be not critical, but the surgeons announced that Lieutenant

Selfridge probably would die. He suffered a fracture of the base of the skull.

Lieutenant Selfridge was perhaps the most enthusiastic aeronautical expert in the army. He certainly was the most experienced in the operation of heavier-than-air flying machines, having made a number of flights in Alexander Graham Bell’s “June Bug.” He was a member of the famous Selfridge family, notable for its naval record.

- WASHINGTON: FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 1908.

- THREE CENTS.

- AIRSHIP FALLS; LIEUT. SELFRIDGE KILLED, WRIGHT HURT

- Propeller Breaks and Aeroplane Dashes to Earth, Burying Occupants in Wreckage.

- GREAT CROWD SEES MISHAP

Wreck of airship, with two victims buried beneath it, taken a minute after the crash.

In the picture is shown army officers and newspaper men moving the debris from the injured men.

Ill-fated Machine, Soaring 75 Feet Above Fort Myer Parade Grounds,

Suddenly Staggers, as Great Blade Snaps Off; Then Turns Over and Speeds to Ground

Signal Corps Officer and Aviator Hurried to Post Hospital, Where the Latter Passes Away

Three Hours After the Accident Without Regaining Consciousness–Wright Takes Injuries Coolly.

News of His Companion’s Fate Is Kept From Him.

KILLED

Lieut. THOMAS D. SELFRIDGE, 26 years of age, native of San Francisco. Residence in Washington, 918 Eighteenth street northwest.

INJURED

Orville Wright, 38 years of age, native of Dayton, Ohio, inventor of the ill-fated aeroplane. Sustained fractures of three ribs and left thigh and slight concussion of brain. Will recover.

Lieut. Thomas E. Selfridge, of the signal corps, was killed, and Orville Wright, the aviator, received a fractured thigh and two broken ribs, late yesterday afternoon, when the latter’s aeroplane plunged to earth during an experimental flight over the drill grounds at Fort Myer. Lieut. Selfridge, who had been taken aloft at his own request, died last night at 8:10 o’clock in the post hospital. Mr. Wright’s condition is not considered critical.

The accident was witnessed by a throng of upward of 2,500 persons, who were instantly changed from cheering enthusiasts to saddened and depressed sympathizers.

The accident was caused by the breaking of one of the propeller blades. It occurred as the machine was making the second turn, at the lower end of the field, on the fourth lap.

Machine Drops to Earth

An end of the blade flew off, and Mr. Wright apparently completely lost control of the machine, which tacked about choppily for a hundred feet or more, soared ten feet higher, and then dropped to the ground with frightful force, from a height of about 75 feet.

The machine crumpled up into a tangled mass of wreckage, burying the two men. The horrified spectators dashed down the field, and those in the van lifted the machine and extricated the victims. Mr. Wright was conscious. Lieut. Selfridge was unconscious, and his face was covered with blood, which gushed from a great gash on his forehead.

It seems to be the general opinion of the experts who have investigated the accident that when the machine hit the ground, both Mr. Wright and Lieut. Selfridge landed on their feet first, and that they were thrown upward and outward by the tremendous force, landing on their heads.

A boy who witnessed the accident from the stone fence which bounds Arlington cemetery, said that they struck in this position.

“They were thrown in the air,” he said, “and then fell forward on their faces.

Both men were removed in a few minutes to the finely equipped post hospital, where they were attended by a corps of army surgeons who happened to be present to witness the flight. Mr. Wright’s condition was early reported to be not critical, but the surgeons announced that Lieut. Selfridge probably would die. He suffered a fracture of the base of the skull.

Was Enthusiastic Aeronautical Expert

Lieut. Selfridge was perhaps the most enthusiastic aeronautical expert in the army. He certainly was the most experienced in the operation of heavier-than-air flying machines, having made a number of flights in Alexander Graham Bell’s “June Bug.” He was a member of the famous Selfridge family, notable for its naval record.

Mr. Wright decided yesterday morning that he would not fly until late in the afternoon, because of the prevailing high wind. He spent some time in the “aerial garage” testing the motor, in anticipation of the flight. The propeller which caused the accident was one of two new ones, which were placed in position Wednesday. After the last two flights of last week, Mr. Wright fancied that the propellers were slightly defective, and ordered a new pair sent on from his Dayton shop, where duplicate parts of the machine are kept.

Decided to Make Flight

About 4 o’clock in the afternoon the wind died down, and an anemometer reading showed that it was blowing at a rate of only six miles an hour. Mr. Wright consulted with Lieut. Selfridge, whom he had decided to take up, heeding the latter’s frequently uttered requests for permission to ride as a passenger, and decided to make a flight.

Lieut. Selfridge had planned to leave tomorrow for St. Joseph, Mo., to assist Lieut. Foulois in the demonstration of the Baldwin dirigible balloon at the military tournament to be held in that city next week, and was especially anxious to fly with Mr. Wright before his departure.

Shortly after 4 o’clock the aeroplane was wheeled up the field and placed in position on the starting track. By that time there were 1,500 persons waiting to witness the flight, including more than 50 automobile parties.

Three members of the aeronautical board, which has charge of the tests, were present, in addition to Lieut. Selfridge, who also was a member of that body. They were Maj. Squier, chief signal officer; Maj. Salzmann, and Capt. Wallace. All of these chatted with Lieut. Selfridge, who was extremely happy when discussing the prospects of the flight.

Expected to Make Long Flight

Mr. Wright busied himself with an inspection of the machine, examining every part of it with minute care. When asked how long he intended to remain in the air, he said: “I cannot tell. It will all depend upon how things look when we get up in the air. Things look favorable for a long flight.”

He had previously confided to a number of army experts that he intended to remain aloft for an hour with a passenger aboard before attempting the official

DIED IN CHOSEN DUTY

Friend of Selfridge Tells of Officer’s Ambition.

ACTIVE STUDENT OF FLIGHT

Young Man Transferred to Signal Corps at His Own Request–Entered Army

After Attempt to Gain Admission to Naval Academy–Worked With Dr. Bell in Experiments at

Badack.

- LIEUT. SELFRIDGE’S CAREER

- Born in San Francisco, February 8, 1882.

- Entered West Point, August 30, 1899.

- Second lieutenant, artillery, June 11, 1903.

- First lieutenant, artillery 1907.

- Transfer to signal corps to carry on aeronautical experiments, 1907.

- Worked with Alexander Graham Bell, and was first man to be carried up In Bell kites.

- Made secretary of Aerial Experiment Association, 1908.

- Supervised construction of aeroplanes June Bug and Red Wing, at Hammondsport, N. Y.

- Made flight In Red Wing, March 12 last.

- Made flight In June Bug in July last.

- Designed propeller of Baldwin airship.

Barbour Lathrop, traveler, man of means, who at different times has been identified with the Department of Agriculture as an expert investigator and adviser, was one of Lieut. Selfridge’s best friends. Mr. Lathrop is in Washington, and is at the New Willard. Of the dead army officer, he said to a Post reporter last night: ‘Tom’ Selfridge was one of the cleanest and one of the most lovable of all the young men I have known. He was born in San Francisco 26 years ago, the son of Mr. and Mrs. E. A. Selfridge, of 2615 California street, that city. The father is now retired and is a man of comfortable means. He was formerly president of the George W. Gibbs company, iron and steel

fabricators.

Lieut. Selfridge is survived by four brothers and one sister. They are E. A. Selfridge, jr., and Russell Selfridge, both of San Francisco; Woodworth and John S. Selfridge, twins, who will enter the Massachusetts Institute of Technology next year, and Mrs. Kellond, wife of Lieut. Frederic G. Kellond, of the Nineteenth infantry.

Came of a Navy Family

“The young man came of a navy family. He was the nephew of Rear Admiral Thomas O. Selfridge, of this city, and if my recollection serves me his grandfather was an admiral, and he has an uncle who is a captain in the army. Young Selfridge himself tried for the navy under the competitive examination system, and passed as an alternate. As such he came from San Francisco to Annapolis; but the regular appointee passed his examinations, and ‘Tom’ was then a trifle too old to enter the acad.

“He turned to the army, and entered West Point August 30, 1899. Notwithstanding a severe illness in his last year, followed by an operation, causing him to be absent from his studies three or four months, he graduated high in his class, that of 1903, and was assigned to the artillery as second lieutenant, June 11, 1903.

“Lieut. Selfridge’s official connection with aeronautics was the upshot of his own desire. His death closed abruptly a career in that field, which he himself had selected. He believed in the heavier-than-air type of ship, and his interest in its development was intense. Two years ago he went to Dr. Alexander Graham Bell, here in Washington, and told him he would like to ask to be detailed to the signal corps and ordered to Badeck, Cape Breton, Dr. Bell’s summer home, to observe and report on the Bell tetrahedral kites.

Detailed to Signal Corps

The idea delighted Dr. Bell, who saw in it ultimate participation by the United Illustration

LIEUT. THOMAS E. SELFRIDGE.

Army officer who lost his life yesterday in the accident to the Wright aeroplane. Lieut Selfridge made his request of the War Department, and it was granted. He was detailed to the signal corps, and all of last summer he spent at Badeck, studying the kites and deepening and broadening his knowledge of aerial navigation.

“He became a member of Dr. Bell’s Aerial Experiment Association, was one of the boys who created the ‘June Bug,’ and was the first man to be carried aloft in the Bell kites. Yesterday’s fatal voyage at Fort Myer was not Selfridge’s first aerial flight. He made a short flight in the ‘June Bug’ at Hammondsport last July. He went up in the ‘Red Wing’ last March.

“‘Tom’ Selfridge was clean strain clear through. He lived blamelessly, and he died, like a man, at his post. Of his personal habits a word may be said with propriety. He was abstemious of stimulants, seldom smoked, except a cigar in the evening, kept himself in splendid physical training, and by that means held down his weight and kept in perfect trim for aerial work. To use a trite expression, he was physically ‘as hard as nails.’

Paid Price With Life

“He had set his heart on flying with Mr. Wright at Fort Myer. He realized his desire, and paid the price with his life. I fancy few men have spent their last hour of consciousness in keener enjoyment. I saw Selfridge this afternoon and watched him as the aeroplane swept through the air above me. His face was set in a smile of pleasure; he was living every minute to its full.

“Saturday night of this week Selfridge was to start for St. Joseph, Mo., to have joint charge with another army officer of balloon tests in conjunction with army maneuvers to be held there. He was to report at St. Joseph next Monday.

“I have no sorrow for him, though I loved the boy and had high hopes of his future. My sorrow is for those he has left behind. He died admirably.”

Lieut. Selfridge was stationed at the Presidio, San Francisco, at the time of the great earthquake and fire in April of 1906. He was one of the young officers who distinguished themselves under Gen. Funston by their capability and courage in handling that chaotic situation.

WILL NOT PROVE SETBACK

Secretary of War Expects Experiments to Be Continued.

Regrets Accident, and States That the Cause Will Be Investigated by Board of Officers.

Word of Lieut. Selfridge’s death was taken to Secretary of War Wright, at his apartments in the Shoreham, last night by a Post reporter.

“It is very sad,” he said, and then asked for a brief description of the accident, of which he had heard only a few words. Commenting on the fatal happening, the Secretary said: “From what you tell me of the accident, it looks as though a structural flaw had caused it; no faulty principle appears. Of course, it is too soon to come to a determination on that point. The signal corps board will have to investigate and make a report first.

“It seems a particularly unhappy thing that disaster should have overtaken Wright, when he had gone so far on the road to success.”

The Secretary of War was asked: “Is it likely the government, out of generosity or any other consideration, will award any part of the contract price to Mr. Wright, in view of the remarkable successes made by him in other preliminary flights?”

Gen. Wright answered: “I cannot say. I do not know that Mr. Wright would wish it. Should such a course seem desirable, the government would make no move until the signal corps board had submitted a recommendation.”

Among the eye witnesses yesterday to the accident to the Wright aeroplane was Charles R. Flint, of New York, international representative of the Wright brothers. Mr. Flint came over from New York yesterday to see the flight, and was accompanied to Fort Myer by Admiral and Mrs. Brownson.

Mr. Flint said last night that the mishap would not cause the Fort Myer flights to be abandoned. They will be resumed, he said, as soon as Mr. Wright has recovered and the machine can be repaired.

KNEW HIS GREAT PERIL

Wright Alive to Dangers of Flight in Aeroplane.

INEXPERIENCE AS A MENACE

Failure to Think Fast Enough in Time of Need Another of the Sources of

Possible Accident Recognized by Aviator. Extreme Caution at All Times Displayed During

Trips of the Aeroplane.

Orville Wright, whose airship was wrecked with fatal results at Fort Myer yesterday had confidently expected to meet all the requirements without a serious flaw developing in the machine his genius had devised. He realized, however, the danger to which the work subjected him. Only a few days ago he said the greatest danger he had to face was his “own inexperience and the possibility that we may do something wrong in making the flights.”

He commented on the change in the methods of operating the levers as compared with his previous machines, and pointed out that where the movements in the old machine were instinctive. this was not the case in the last machine, and that with the latter the operator had “to think, which is dangerous on account of the possibility of not thinking fast enough.”

Always Extremely Cautious

Mr. Wright exercised what he believed to be extreme caution in starting his flights. Time and again he planned to make a flight, but as the hour he had tentatively fixed arrived he refused to take out his machine because of unfavorable conditions. He had been out in a 12-mile wind in previous flights, but an 11-mile breeze a day or two ago served to deter him.

In the first flight at Fort Myer, Wright made one of the mistakes he had feared and pulled the lever in the wrong direction. Fortunately, the machine descended without damage.

“I have flown in a 20-mile breeze,” said he, “and I expect to do so again, but not until I get acquainted with the arrangement of seats and levers.”

Nearly all the members of the signal corps aeronautical board witnessed yesterday’s accident. Among them were Maj. George O. Squier, Maj. Charles McK. Saltzman, Capt. Wallace, and Lieut. Frank P. Lahm. Lieut. Sweet, of the navy, and Lieut. Richard B. Creecy, of the marine corps, both detailed to the aeronautical tests at Fort Myer, also were present, as was Maj. Fournier, military attache of the French government.

Among the spectators were scientists and persons prominent in official life.

He climbed into the machine first, and Mr. Wright followed him, giving him specific instructions as to how to sit during the flight.

“I don’t have to tell you to keep your nerve,” said the aviator. “You’ve been up often enough to know how to do that. Just sit tight, and don’t move around any more than you actually have to.”

Machine in the Air

The lieutenant waved a good-by to his friends, as Mr. Wright’s assistants turned the propellers, thus starting the motor. In another instant the big blades were whirring around at a tremendous rate of speed. Mr. Wright gave the signal to start, and the soldiers holding the rope attached to the weight let go.

Aeroplane Begins Fated Flight

The aeroplane glided down the track with its accustomed speed, but when it left the rail it seemed to the spectators as if it was not going to rise. It actually slid along the ground for nearly a hundred feet, not merely skimming the tops of the grass blades, as on previous occasions, but actually slipping along the earth. Slowly it lifted itself into the air, rising higher and even higher, until it was fully 75 feet above the ground, when the first turn at the lower end of the field was made.

There was not the steadiness observable which had previously been noted when Maj. Squier and Lieut. Lahm were taken up. It rounded the curve near Arlington Cemetery with grace and ease, and came sweeping up the field at a height of 100 feet or more. The crowd cheered mildly as it passed overhead and sailed down the field again.

It was noticed that Lieut. Selfridge was apparently making an effort to talk with Mr. Wright. His lips were seen to move, and his face was turned toward the aviator, whose eyes were looking straight ahead, and whose body was taut and unbending.

Makes Turns With Ease

Three times the machine circled the field at about the same average rate of speed which had been attained on previous flights, 38 miles an hour. It seemed to be behaving wonderfully well, and the crowd was beginning to lose its first intense interest, and conversation was being indulged in.

The aeroplane swept around the first curve, at the lower end of the field, with the same ease which had characterized other turns. At a point near the “aerial garage” the spectators saw a fragment of something fly from the machine and describe an arc in the air.

“That’s a piece of one of the propellers,” shouted one of the officers. “I wonder what will happen to — My God! they’re falling!”

At his first word the spectators watched with that fascinated horror which comes to those who know that disaster is impending, and yet who realize they are helpless to avert it. Women gripped their escorts’ arms, and the tensest sort of silence prevailed.

Wavers in Air, Then Falls

They saw the aeroplane start on the second turn, which it was just beginning to take which the propeller broke. It twisted this way and that, like a ship in the grip of mountainous waves. It turned sharply toward the cemetery, darted back again toward the upper end of the drill grounds, shot ten feet higher into the air, and then dashed to earth in a downward curve. It struck with terrific force, throwing up a cloud of dust, and collapsing like a house of cards.

The crowd surged out upon the field, and started a wild dash for the wrecked machine, headed by the newspaper correspondents, who had places on the field, and who were able to reach the spot first. Cavalrymen, who had been holding the crowd back, rode at a gallop down the field, as did Lieut. Lahm, who had sprung upon his horse at the first sign of danger.

Both Buried Under Wreckage

Three mounted soldiers who were on duty at the lower end of the ground and a half-dozen newspaper men were the first to reach the machine. One look underneath showed them that the two men were pinned in by the wreckage. The aeroplane had crashed to earth front end first, and the upper planes were resting upon Mr. Wright and Lieut. Selfridge, who were lying face downward on the ground, their faces buried in the dust.

Three or four other soldiers who came up in a moment helped lift the machine up, and the two aeronauts were lifted out by the newspaper men and the first soldiers who had arrived.

Mr. Wright was taken out first. He opened his eyes for a brief instant as he was laid tenderly upon the grass. He was moaning softly, and seemed to be in great pain. There was a cut over his left eye, and his clothing was covered with grime and dust.

His assistant, C. E. Taylor, who came up at this moment, helped take out Lieut. Selfridge, whose face was covered with blood, flowing from a six-inch gash on his forehead. This gash had been caused by one of the supporting wires against which he had fallen. The lieutenant was unconscious and his respiration was poor.

Machine which brought death to one passenger and serious and serious

injury to another, after making many successful flights

Mr. Taylor walked over from where he helped place the lieutenant and stood over Mr. Wright, with whom he has worked for four years. He stooped for a moment and opened his employer’s shirt. Then he stepped back. and, leaning on a jagged corner of the broken aeroplane, sobbed like a child. His grief was so pitiful that one of the newspapermen walked over and put his arm around his shoulder.

“It’s all right, old man,” he said gently. “The doctors will be here in a minute or two and they’ll fix him up.”

But Mr. Taylor was past comforting just then. Watching a man cry isn’t pleasant, and every one turned away to help care for the injured men. Dr. J. A. Watters, of New York, who was present as a spectator, was one of the first physicians to arrive. He forced his way through the cordon of cavalrymen, which had been hurriedly thrown around the wrecked machine, and bent over Mr. Wright, who opened his eyes and whispered: “It’s my leg, doctor, and my chest. They hurt me fearfully.”

Da. Stuart C. Johnson, of this city, also hurried to Mr. Wright’s assistance.

Three surgeons from the general staff, Maj. Crosby, Maj. McCaw, and Maj. Ireland, who had been watching the flight from a motor car, dashed up in the machine just then and turned their attention to Lieut. Selfridge, who lay immovable his head pillowed in a soldier’s lap, and the blood trickling from the great gash down his cheek and onto his shirt front.

A hurry call had been sent for the hospital corps, and a half-dozen orderlies arrived within three minutes after the fall. They brought two stretchers with them. The injured men were lifted onto these and were carried up the field to the post hospital, surrounded by a dozen cavalry-men, who had great difficulty in keeping the crowd back.

Machine a Mass of Wreckage

Mr. Taylor had recovered himself, after having been informed by Dr. Watters that Mr. Wright did not seem to be dangerously hurt, and began the work of getting the wreckage into the “aerial garage.”

The front planes had struck the ground first, and had been crushed into small pieces. The rods supporting the main planes had been ground to a shapeless mass and the canvas was torn in a score of places. The skids were smashed into kindling wood. The right propeller was intact, but the left propeller was broken off at both ends. The piece which had caused the accident had snapped off about a quarter of the distance from the hub. From the peculiar nature of the propeller’s construction, according to experts, if one end snapped off, the other also would break. The other broken piece dangled by a shred of fiber.

The motor did not seem to be irreparably damaged, but the gasoline tank had been pierced and its contents had spilled out. While Taylor was examining the motor he suddenly shouted:

Wright Had Shut Off Motor

“Why, it’s shut off. He must have realized his danger and tried to glide down.”

Up at the post hospital, in the meantime, a group of solemn-faced army officers were gathered on the front porch waiting for news from the operating room upstairs, where the surgeons were working over the injured men. With them were Maj. Fournier, the French military attache; Octave Chanute, the theoretical aeronautical expert and adviser of the Wright brothers, and Charles R. Flint, the New York capitalist, who is their financial representative, and who had come to Washington to consult with Orville Wright on business matters.

An air of deep depression brooded over the scene. All of these men were friends of the two victims; they had seen them half an hour before full of the joy of living, alert and keen-eyed. They had seem them a few minutes later bleeding and seriously hurt, and the thought of it filled them with grief.

Maj. Squier was particularly affected. He walked up and down the porch with his hands behind his back and his Panama hat pulled down over his face, a picture of dejection.

“It’s frightful! It’s frightful!” he kept repeating. “Just at the moment of success, too.”

A few moments later he went upstairs and remained for a short time. When he came down he called the newspaper men over.

Dinner Engagement Wright’s Worry

“I’m afraid it’s all up with poor Selfridge,” he said, “but I don’t think Mr. Wright is as badly hurt as we at first supposed. His leg is broken, but I don’t think there is anything more serious. What do you suppose he said to me when I went up there? He looked up while the surgeons were working and smiled faintly. ‘Well, major,’ he said, ‘I guess we won’t be able to keep that dinner engagement, will we?’

“You see we had planned to take dinned with Brig. Gen. Crozier, chief of ordnance, and I was to have taken Mr. Wright over in the motor car. Think of that for nerve and self-possession after what’s happened.”

The surgeons sent down a bulletin within a few minutes, announcing that Mr. Wright had sustained a fracture of the left thigh and of several ribs on the right side, and that he had been “much shocked, but had reacted well.” This bulletin also announced that Lieut. Selfridge had sustained a fracture of the base of the skull and that his condition was “extremely critical.”

One of the surgeons who came downstairs shortly after admitted that he did not think the lieutenant could possibly live.

Never Regained Consciousness

Lieut. Selfridge died about five minutes after he was operated on, without regaining consciousness. The surgeons who performed the operation, Maj. Crosby, Maj. Island, Maj. McCaw, and D. L. L. Waters, of New York, were present when he breathed his last. News of the lieutenant’s death was immediately transmitted to the War Department and to his family.

The operation consumed about 40 minutes. Superficial examination of the injuries on the grounds developed that the officer had received a fracture of the skull, which probably would prove fatal were he not operated on. When Lieut. Selfridge had been placed under anesthetics, Maj. Crosby made an incision about 4 inches long on the left side of the head, above the temple, at which point the skull had been crushed. A diagonal piece of the bone, about 2 inches in length, was removed, under which was found a clot of blood. About five minutes later Lieut. Selfridge died.

Dr. Howard H. Bailey, who attended Lieut. Selfridge, made the first announcement of that officer’s death. Just after the lieutenant had passed away, the doctor came out of the room, and to those awaiting in the hall, he said, “He is dead.”

Compound Fracture Fatal

“His death,” said the doctor, “was due to a compound fracture at the base of the skull. He never regained consciousness from the moment he struck the ground, despite the heroic remedies which were administered. There was absolutely no response to the treatment given him. He passed away peacefully “Maj. Squler has advised the family.

THINKS OF SHIP FIRST

After Rallying Wright Asks for Octave Chanute.

EAGER TO TALK OF MISHAP

Inventor Anxious to Find Out Why Accident Occurred–Surgeons Refuse to

Permit Conversation — Mr. Chanute Tells of Crash, and Says Propeller Was

Defective–Experiments to Continue.

Rallying quickly from his severe injuries sustained in the accident at Fort Myer, Orville Wright last night sent Lieut. Lahm to find Octave Chanute, the pioneer aeroplanist, who aided the Wright brothers in their first gliding experiments.

Mr. Wright wanted to discuss the cause of the accident with Mr. Chanute, but the physician decided it would be best that Mr. Wright should not exert himself to that extent.

Propeller Defectively Fastened

Mr. Chanute was keenly affected by the accident and there were tears in his eyes as he talked to the newspaper men.

“It’s a pity, a great pity,” “he said. “to think that this should happen just at the moment when Mr. Wright’s praises were being sung all over the world.”

When asked to give his explanation or the accident he said: “The broken propeller was entirely responsible. It would seem to have been defectively fastened together. You will understand that these propellers are made of strips of wood which are glued together. When that end flew off the other end broke in sympathy with it, I might say, and rendered it impossible to control the machine with the other propeller whizzing around at its accustomed speed. I would not care to indulge in any extended explanation until I have investigated the matter further.”

“Would it have made any difference if there had been only one propeller instead of two?” asked one of the correspondents. “Would it have been possible to glide to earth safely in such an emergency with only one propeller?”

“I do not think so,” replied the expert. “I fancy that if there had been one propeller the machine would not have remained aloft as long as it did after the end flew off, and that it would have fallen to earth even more sharply.”

Opposed to Aluminum Propellers

“Will this cause the use of aluminum propellers?” was asked.

“Most decidedly not,” replied Mr. Chanute. “They have been found impracticable. It will cause the use of much stronger wooden propellers, however.”

“Then aerial navigation is not altogether safe as yet. is it?” ventured another correspondent.

“Those of us who have studied the problem carefully have always known that it was far from safe as yet,” was the reply.

“Will this accident have the effect of discouraging experimentation?”

“It may for a time, but not for long. Other experimenters have been killed before, but the scientific investigation of the problem has gone forward regardless of this.”

A message was sent to Wilbur Wright, in France, urging him not to worry.

“Mr. Wright seemed greatly concerned about the members of his family,” said the major. “They were his first thought.”

That his second thought was for his machine, and that he was trying to solve mentally the problem of the accident, was evidenced by a request which he sent out by one of the hospital orderlies within an hour after he was taken into the operating room.

“Tell Taylor to see if there was anything the matter with the transmission,” was the message.

When Taylor heard that he smiled once more.

“That proves he’s all right,” he said, heartily. “I’m mighty glad of it. He’s the best chap in the world.”

Taylor discussed the probable cause of the accident at some length.

“I saw the whole thing at pretty close range,” said he. “I think the reason the machine fell was because he could not glide down while making a sharp curve. If that propeller had broken while he was sailing along on a straight course, I am convinced he could have shut off the motor and glided down to the ground safely. I think he tried to turn the front planes down, but they wouldn’t work while sailing around a curve. That’s why she fell. That’s my opinion, and I’ve seen a great many flights and know quite a little about the control of the machine.”

WITNESSES TELL OF MISHAP

Charles White Declares Whirring Blade Gave Impetus to Downward Plunge of

Fated Aeroplane–Blames Wood Construction of Propellers, Which He Had

Pronounced Faulty.

Charles White, of White & Middleton, Baltimore, Md., a mechanical expert, gave this description of the accident to Wright and Selfridge:

“I witnessed the flying of the aeroplane and it was performing beautifully for six or seven minutes, when suddenly one of the propellers broke near the end. This caused the machine to become so thoroughly out of balance through centrifugal force as to make it unmanageable, and it made a dart to the ground while still under operation of the right propeller, causing it to strike the ground with a great deal more force than it would have done by gravity.

“I do not feel that this is any serious defect in the machine, but merely want of better construction in the propellers. Therefore, I do not feel that the machine should be condemned beyond this point.

Fell Twenty Miles an Hour

“I should imagine that when the machine made the dart for the ground it fell at the rate of 20 miles an hour. I saw the piece that flew from the propeller fall to the earth. Before the flight of the machine I examined it thoroughly and saw nothing to be criticised outside of the wood construction of the propellers.

“Before the machine made the flight. I remarked that the wood propellers were not of the proper construction. Three seconds after the accident happened the big machine appeared like a bird with a broken wing. The forward side of the machine struck the ground first.

“Wright and Selfridge were in their usual positions on the seats when they landed. They were not thrown out. All the mechanical devices remained intact, though the braces and canvas work was wrecked. The accident was due entirely to the defective propeller.

“The aeroplane was under perfect control, and the accident was certainly not due to any fault of operation.”

Selfridge Waved at Friends

“It was a change from a scene of enchantment to a picture of horror,” said John B. McCarthy, of 248 Third street, a spectator of the accident.

“I had been attending a funeral in Arlington Cemetery and, learning that the ship was to sail, walked over the field, arriving just as the ship started. The emotions aroused as one watched the craft sailing about so lightly and easily cannot be described. I was standing in the part of the field nearest the homes of the army officers, and evidently a number of the friends of Lieut. Selfridge were in the group near

me, for as the airship passed over us, Lieut. Selfridge took off his cap and waved it at a number of the ladies and men in the party and said something to them which I did not hear.

“He was smiling and laughing. The group responded by applauding and cheering. Mr. Wright wore his little Scotch plaid cap and seemed to be engaged in guiding the machine.

“The car must have gone nearly a quarter of a mile from us when something seemed to go wrong, and an object fell from the car. Mr. Wright at the time evidently was trying to steer the car around a curve. Immediately the car dropped on one side and began flopping and turning around exactly like a chicken or bird with a broken wing. Then it fell with a crash to the ground.

“Women and men around me shrieked. One woman and a big, imposing-looking officer fell in a dead faint. I understand this officer was the man who induced Lieut. Selfridge to make the trip.”

Described by Maj. Magoon

Maj. Magoon, the superintendent of Arlington Cemetery, witnessed the accident from the edge of the cemetery. In commenting upon it, he said:

“When I saw the propeller blade break and the piece fly away, I knew something was going to happen. I was watching Mr. Wright at the time. I was within a few hundred feet of him. He did not look around, but I could see him turn one of the levers. The aeroplane started over toward the cemetery at first instead of continuing the curve which it had started to make, and I stood aghast, fearing it would alight on the trees.

“I could feel that it was coming down. It careened from side to side, turned first in one direction and then in another, and finally started up the field again. Then it sailed a little higher in the air, and then it just dropped straight down. From where I stood I could not see the men when it struck the ground. The machine went to smash in the twinkling of an eye. All that I have told you happened in a few seconds, probably two or three, but it seemed a much longer time.”

WILL NOT DETER BROTHERS

Lorin Wright Expects Them to Continue Airship Flights.

Dayton, Ohio, Sept. 17–Lorin Wright, brother of Orville Wright, Said, when informed tonight of the accident to the Wright aeroplane at Fort Myer today:

“The spruce used in the propellers was selected for its great strength in proportion to its weight, and the blades were more than three and one-half inches thick at the point at which the shaft pierces them,” he continued.

“The motor exerted no more power than any of those used in recent flights, which makes the accident inexplicable to me.”

When asked if the accident would deter either Orville or his brother, now in France, from further tests he replied emphatically:

“Decidedly no! My brothers will pursue these tests until the machines are as near perfect as it ‘s possible to make them, if they are not killed in the meantime. We have never felt much apprehension, knowing that both boys are cautious in the extreme.”

The aged father of the injured man is at Greens Fork, Ind., and will not be advised of the accident until morning.

Lorin Wright and his sister, Catherine, here await with much anxiety the outcome of their brother’s injuries.

WILBUR WRIGHT STILL FLYING

Injured Aviator’s Brother Stays Up More Than Half an Hour.

Le Mans, France, Sept. 17.–Wilbur Wright, the American aeroplanist, spent today in trying out his machine for the protracted effort he is to make tomorrow. In one of his short flights he covered 4,600 yards in 6 minutes 43 seconds.

Mr. Wright made another fine flight tonight, remaining in the air 32 minutes and 47 seconds. He traversed a distance of about 20 miles at an average height of 60 feet, only descending on account of darkness.

Paris, Sept. 17.–Flying at Issy today, Leon Delagrange stayed aloft in his aeroplane for 30 minutes and 20 seconds. After alighting he expressed the hope that he would shortly be able to surpass the records made on both sides of the Atlantic by the Wright brothers.

Baldwin Airship Up Today

St. Joseph, Mo., Sept. 17.–Preparations are under way at the army encampment in South St. Joseph to have a trial flight tomorrow of the Baldwin dirigible balloon, which has been installed there awaiting the miltary tournament next week.

MAY AFFECT APPROPRIATION

Signal Corps Official Thinks Accide?? Will Influence Congress.

Officers of the signal corps and otherr enthusiasts at Fort Myer were incline to express the belief that the accident was not due to a fault of principle, but to a defect in the propeller, which was made of spruce. One of the members of the signal corps boards who had been conducting the tests said:

“Of course, this is no time to discuss such matters, but the resumption of the aeroplane trials will depend on the length of time which it will take Mr. Wright to recover from his injuries. This accident will, of course, seriously hamper the possibility of securing appropriation from Congress for the aeronautical section of the signal corps. The Wright brothers, however, have even more advance ideas in regard to aerial flight, and they continue their work it is probable the effect of this one accident will be overcome.”

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard