VIETNAM WAR MIAS IDENTIFIED

The remains of two U.S. Air Force servicemen killed in action during the Vietnam War have been identified and are being returned home to their families. They are Master Sergeant Thomas E. Heideman and Captain Craig B. Schiele, both of Chicago.

On October 24, 1970, Heideman and Schiele were crewmembers of a CH-3E helicopter as the lead of a two-ship formation on a mission to extract friendly forces from Laos. Shortly after takeoff, the helicopter crashed into nearby dense jungle. Eight Laotians and two American servicemen were rescued. A rescue mission was continued the next morning, but there was no evidence of survivors. The only body recovered from the crash site at that time was later identified as the pilot, Captain Schiele, who was subsequently buried in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.

On December 14, 1994, a U.S. – Lao team, led by Joint Task Force-Full Accounting, conducted an investigation at the crash site in the Laotian province of Khammouan. Material from the recovered wreckage included aircraft debris and personal

artifacts but no human remains.

In the spring of 1995, a second joint team excavated the crash site and recovered human remains and additional personal affects that were submitted to the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory, Hawaii (CILHI). By compiling eyewitness accounts

and other physical evidence such as personal artifacts and the human remains, the forensic scientists at CILHI identified the remains as those of Schiele and Heideman.

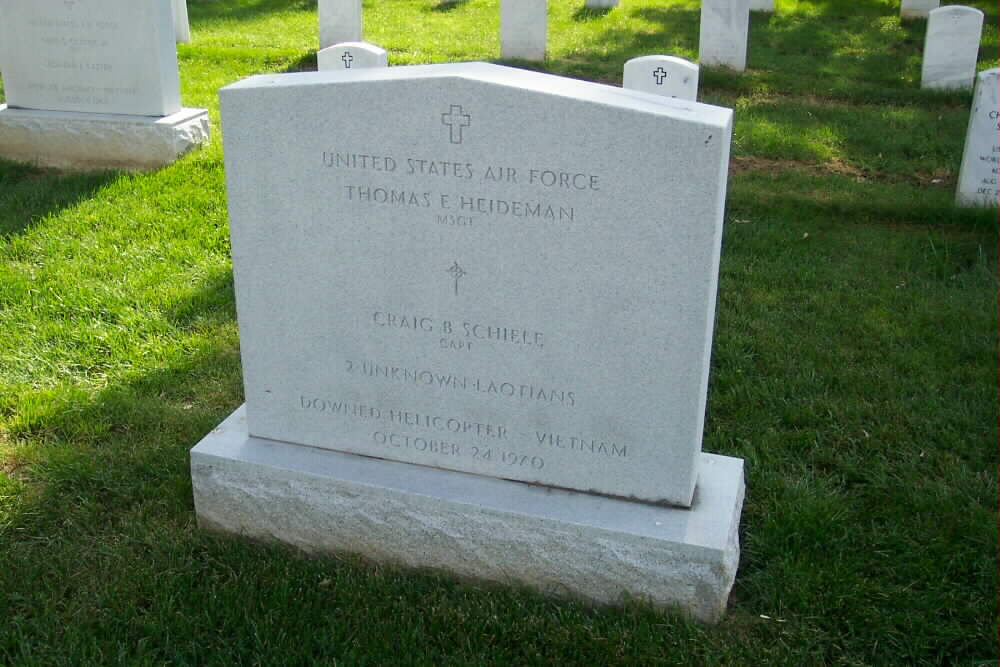

A group burial with full military honors for these two servicemen will be conducted June 7, 2002, at Arlington National Cemetery.

The remains of two Chicago-area airmen killed in a risky Laotian mission during the Vietnam War have been identified and will be buried this week at Arlington National Cemetery, the Pentagon said Monday.

Air Force Master Sergeant Thomas E. Heideman and Captain Craig B. Schiele were killed October 24, 1970, while serving as crew members of a CH-3E “Black Maria” helicopter sent to rescue friendly forces from Laotian territory.

Piloted by Schiele, their helicopter was the lead ship of a two-aircraft contingent carrying out the rescue at a time when large-scale North Vietnamese forces were operating in Laos.

The friendly Laotian troops were taken aboard, but, shortly after takeoff, Schiele’s helicopter crashed in dense jungle. Eight Laotians and two American servicemen survived the crash and were quickly rescued, but a second attempt aimed at

retrieving Schiele and Heideman could not be mounted until the following morning.

The partial remains of one of the two fliers were recovered and later identified as Schiele. They were buried at his family’s request in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. His only sister, Lynne Schiele of Hazel Crest, who was four years younger, said her brother,

who was 27 at the time of his death, was buried in the family plot of his wife, Margery, in her hometown of Bartlesville.

Schiele was a 1966 graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a native of west suburban Lombard, his sister said Monday. The Schiele family moved from Illinois to Steubenville, Ohio, after Schiele had completed his second year of high school at Glenbard High School.

Because Schiele received a draft number indicating he would likely have to serve in the armed forces, he enlisted in the Air Force after college graduation “to choose his own course” and was first in his officer candidate class, his sister said. His wife had been living in Oklahoma at the time of his death, Lynne Schiele said.

At the time of the rescue effort that uncovered Schiele’s remains, there was no sign of Heideman, then 37. His mother, Olivette, lived at 1617 W. 83rd St. in Chicago. In 1971, he was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal and the Commendation Medal, which were accepted by his wife, Patricia, in ceremonies at Shaw Air Force Base, South Carolina.

Though the U.S. had been conducting widespread covert operations for some time in Laos, it was not until November 1970 that it became a significant battleground of the war, with large South Vietnamese army units moving in against communist elements there.

U.S. ground troops had been banned from use in Laos, and most of the fighting there was conducted by friendly Laotian and South Vietnamese forces.

With the cooperation of Southeast Asian governments, the U.S. in the 1990s began an effort to locate and identify the remains of U.S. troops reported missing during the war. On December 14, 1994, a joint U.S.-Laotian recovery team visited the crash site in Laos’ Khammouan province, and recovered helicopter debris and some personal artifacts but no human remains.

The next spring, a second recovery team searched the area and excavated the ground, this time discovering human remains as well as additional personal artifacts. These were taken to the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii.

After a long, painstaking investigation by forensic experts involving scientific analysis of the human tissue, as well as examination of the personal effects and eyewitness accounts of the incident, the Pentagon said the remains belonged to Heideman and Schiele.

Lynne Schiele said a report she received following the identifications stated that though DNA testing was done on the remains, they could not be positively identified as a specific person. Two Laotian soldiers also died in the crash.

“My understanding from the report that I received was that none of the remains could be identified with any one of the four people who died,” Lynne Schiele said. “The only reason the site was excavated was to determine the status of Master Sergeant Heideman. It could not be positively identified, which is why it’s a group burial.”

Heideman’s remains and Schiele’s partial remains will be buried Friday at Arlington in a group service with full military honors. Despite lingering questions about the exact nature of the accident that killed her brother, Lynne Schiele said she and some of her cousins will attend the ceremony.

From a press report: 8 June 2002

For the two families, decades of searching for answers came down to this: a closed coffin, a bugler’s notes, flags folded and handed to them with salutes.

The Air Force honor guard, the horse-drawn caisson and the 21-gun salute at an Arlington National Cemetery grave Friday signaled an end to the Defense Department’s inquiry into the Vietnam War deaths of Air Force Master Sergeant Thomas Edward Heideman and Captain Craig Brian Schiele.

But the military burial on a warm, overcast day served only to quiet the nagging doubts of the two Chicago-area men’s relatives, not end them.

The Defense Department says the two helicopter crew members died in Laos while rescuing Laotian soldiers during the Vietnam War.

After a long, painstaking investigation, the department determined the remains found in Laos and laid to rest Friday were those of Heideman, Schiele and two Laotians.

Most of Schiele’s remains were recovered from the wreck of the CH-3E ” Black Maria ” helicopter soon after the 24 October 1970 crash. Those identified as Heideman’s were not found until the crash site was excavated in 1995 by the United States military investigators.

Though Heideman’s mother, Olivette, 92, says she finds ” closure ” in the burial, his children still question whether the remains in his casket are really the remnants of their father’s body, lost three decades ago in the Laotian jungle.

“To me, it will be closure, because I understand that his file will be closed,” said Olivette Heideman, her eyes filling with tears. “and if that’s closed, I’m sure nothing could ever be done after that — 32 years is a long time to wait. So, hopefully, he’s at rest.”

A report given to the family detailing how the remains were dentified only opened up more questions, Heideman’s oldest daughter said this week.

“The only way that they came to that conclusion is that they were saying that he was on the helicopter when it crashed,” said Mary Ann Buonforte, 46, the oldest of Heideman’s four living children, who was at her grandmother’s side throughout the ceremony Friday. “There’s absolutely nothing in the … report that is positively identified as being his.”

Photographs of the personal effects found along with the remains revealed nothing that belonged to her father, Buonforte said. And she and her siblings found nothing of Heideman’s when they examined the materials in person Thursday, though one of her sisters took as a keepsake a nickel dated 1970.

It was the only thing they could touch to remind them of a man who had only two more years left in his military career when he died.

His mother said Heideman, whose 69th birthday would have been Saturday, grew up on the South Side, went to Calumet High School and joined the Air Force after deciding he disliked Northwestern University.

“He didn’t want inside work, and I had a nephew who was in the service at that time, and he talked to Tom, and Tom decided to join,” his mother said.

In the next two decades, he and his growing family moved several times, eventually spending three years in Italy before settling in South Carolina, where Buonforte and other family members still live.

He was stationed at Shaw Air Force Base there until he went to Southeast Asia in the spring of 1970.

One Sunday a few months later, his wife and children were called from church to learn of his death.

DAUGHTER TAKES OVER SEARCH

Since the crash, Heideman’s family has never given up hope they might find out for certain what happened to him. His wife and mother both tried to extract something about the accident from the military.

“I wrote to numerous people, not recently, but in the beginning, to find out what happened,” his mother said. “They couldn’t tell us.”

Heideman’s wife, Patricia, died in 1979, and their youngest son died in 1995. As years turned to decades, Buonforte took over the search her mother and grandmother had begun.

“About every five years, I would send a [Freedom of Information Act] request to the different offices. Every so often, different things would get declassified,” Buonforte said.

The misgivings that plague Buonforte and her siblings are shared by many families of those missing in action. Quieting this doubt is one of the roles of the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office, a spokesman for the office said.

“Part of the thing is just the human issue that families are concerned. They are looking for closure,” said Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Erstfeld.

The process of identification can be long and slow. Buonforte was first told human remains had been found at the crash site in central Laos in 1995. At the time, officials said they might know within six months if they included her father’s remains. But the bones were too fragmentary and decayed to yield any DNA, results, and the probe dragged on.

TERROR ATTACKS DELAY BURIAL

In their first determination, military investigators relied on helicopter parts that proved that they had the right accident site, and on eyewitness accounts that placed Heideman on the aircraft, and pointed to him being one of those who died.

Originally, Heideman and Schiele’s families had planned to travel to Arlington for a group burial on 14 September 2001, but the service was postponed until this week because of the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001, Buonforte said.

The determination on Heideman and Schiele’s remains is in line with many of the 52 Vietnam War MIA identifications made last year by the military, Erstfeld said.

“Well over half of the identifications that are made are not based on DNA tests,” Erstfeld said.

Lynn O’Shea, the New York state director of the National Alliance of Families, a POW / MIA group, criticizes the military for worrying more about crossing names off a list than about finding the truth.

“Their goal is to reduce the list of the unaccounted for as quickly as possible,” O’Shea said.

Despite the lingering uncertainties, the two servicemen’s friends and family said they were thankful for the burial.

Former Air Force Sergeant Wallace Spivey, the only living survivor of the crash, drove from Philadelphia to see his comrades buried. He still declines to speak openly about what happened almost 32 years ago.

“I’m here to honor the guys from my crew and maybe get a little closure for myself, like the families,” Spivey said after the burial.

Schiele’s only sister, Lynne, and his widow, Marjorie Lawrence, said they were happy to meet Heideman’s family, Friday, and they were pleased to see Schiele honored.

“There is a lessening of the pain, but you never forget someone you loved so deeply,” Lawrence said.

June 6, 2002

A former Shaw airman will be laid to rest Friday in Arlington National Cemetery — nearly 32 years after his plane crashed in a Laotian jungle. Master Sgt. Thomas E. Heideman of Chicago was a crewmember of a CH-3E helicopter sent to rescue Laotian allies during the Vietnam War. Shortly after takeoff on Oct. 24, 1970, the helicopter crashed. A rescue mission the following day identified no survivors. Two more missions followed, including one in 1995 during which 317 bone fragments were recovered. From these remains, as well as other physical evidence such as personal articles, forensic scientists at the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii identified Heideman as well as Capt. Craig B. Schiele, also of Chicago. Schiele’s body had originally been recovered the day after the crash. His arm, however, was not found and is believed to be part of the 317 bone fragments.

And while many families have agonized about soldiers lost in action during the Vietnam War, Heideman and Schiele’s families have mixed feelings about the recent discovery.

Heideman’s mother, Olivette, now lives in Florida. “What I’ve always wanted to see was his name on a cross at Arlington,” the 92-year-old said of her only son. “I feel it’s closure. How many more years would I have to wait to see his name on a cross?”

“She feels like he deserves this honor,” Heideman’s eldest daughter, Mary Ann Buonforte, said of her grandmother. “She’s right, he does.”

Now residing in Columbia, Buonforte was 14 when her father left for the war and 15 when the crash happened. While she says Olivette has yearned for the ceremony at Arlington, Buonforte said she won’t be comforted herself. “This doesn’t give me a sense of closure. This is a group burial, not an individual one,” Buonforte said, voicing doubts that her father’s remains are among the bones found. Buonforte says she has documents that indicate the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office, which led the search, couldn’t perform DNA testing because the bone fragments were burned so badly.

Sandy Evans, another of Heideman’s daughters, corroborated Buonforte’s statement. “None of the remains have been identified as him,” she said. “My grandmother donated her blood, but they couldn’t do the DNA testing. But because they assumed he was at the crash site, they went ahead and assumed it was him.” She went on to add that military officials even briefed the family that none of the remains could be identified as her father.

A spokesman for the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office, Larry Greer, admits DNA testing was not possible, but remains confident in the other investigative measures used to identify Heideman.

“The identification process we used is the same one that’s applied when you have a number of people who died at the same time, like any major airplane disaster, even September 11,” he said.

He added that mostly circumstantial evidence — some of which included a “home investigation” — led to the conclusion that the remains were Heideman.

Still, Buonforte and Evans remain unmoved. Another daughter, Sumter resident Cathy Long, could not be reached for comment.

“They don’t address some things,” Buonforte said. “The conflict in the number of bodies that were seen at the crash site the day after versus the number of people that were accounted for, and all the reports we got from when the crash happened refers to there being three sets of remains found at the crash site, and one was Capt. Schiele.

“And I’m not so sure if he (Heideman) was actually on the helicopter,” she said. “They had just picked up a bunch of Laotians, and there was ground fire all around. In fact, one of the crew chiefs that survived claimed he never saw my dad on the helicopter, and none of the personal articles or artifacts that they recovered are his.”

Schiele’s widow, Marjorie Lawrence of Texas, shares Heideman’s daughters’ frustration.

“At the time (1970), the military shipped home the body and gave him a full military service,” Lawrence said, adding it was hard to bury her husband on her 24th birthday, but she still got a sense of finality. “Now, 30 years later, they say they didn’t get him all, and let’s do this again? I find this very disturbing.”

But the conversation of the family members quickly turned from their increasing irritation to positive memories of their lost soldiers.

“He was quiet and very hardworking,” Buonfort said of her father. “He was a wonderful young man,” Heideman’s mother added. “He was a wonderful father, son and human being, and as I understand it, an excellent soldier.”

Schiele, described as “brilliant” by his widow, attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology before enlisting. “He was funny, generous and a very loving and giving person,” she said. But she maintains there is no such thing as closure. “In all the discussion today, the favorite buzzword is closure,” Lawrence said. “There is no closure, there is just learning to cope with the loss and the pain.”

The service will be held at Arlington National Cemetery Friday with full military honors. The headstone will have both Heideman’s and Schiele’s names.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard