Full Name: STUART MERRILL ANDREWS

Date of Birth: 9/22/1928

Date of Casualty: 3/4/1966

Home of Record: STAMFORD, CONNECTICUT

Branch of Service: AIR FORCE

Rank: COLONEL

Casualty Country: SOUTH VIETNAM

Casualty Province: PROV UNKNOWN, MR II

Status: MIA

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense

(Public Affairs)

NEWS RELEASE

IMMEDIATE RELEASE No. 586-06

22 June 2006

MIA USAF OFFICER FROM VIETNAM WAR IS FINALLY IDENTIFIED

The Defense POW/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) announced today that a United States Air Force officer Missing In Action from the Vietnam War has been identified and is being returned to his family for burial with full military honors.

He is Major John Francis Conlon III, originally from Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

His funeral is tentatively scheduled for Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, D.C., in the fall.

On 4 March 1966 Conlon and Colonel STUART MERRILL ANDREWS took off from Qui Nhon Air Field, Binh Dinh Province, South Vietnam, in their O-1E ” Bird Dog ” light observation aircraft.

They were on a visual reconnaissance mission to Cheo Reo, an airstrip approximately 60 miles southwest of Qui Nhon.

The last radio contact with the crew was with a U.S. Army Special Forces Camp about 30 minutes after take-off.

The crew reported the aircraft’s position but made no mention of problems.

When the aircraft failed to arrive at Cheo Reo, a search and rescue effort was initiated, but failed to find the aircraft or crew after six days of searching.

Between May of 1993 and August of 2005 teams from the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) conducted six investigations in the Binh Dinh Province.

They developed leads which took them to a site which was later scheduled for excavation.

In February of 2006 a joint JPAC-Vietnamese team excavated that site and found aircraft debris, personal effects, human remains and a dog tag that related to Conlon’s crew.

JPAC scientists used Conlon’s dental records to confirm his identity from those remains excavated at the site.

Of those Americans unaccounted-for from all conflicts, 1,803 are from the Vietnam War.

From a news report: 15 September 2006

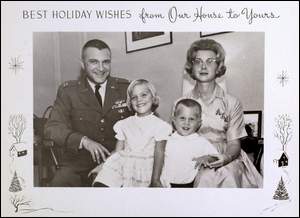

When Ann Andrews was told her long-missing husband’s remains had been found, the loving wife had emotions some might find surprising — relief and gratitude.

Major Stuart Andrews, an Air Force pilot, took off on March 4, 1966, on what was thought to be a routine reconnaissance mission over South Vietnam, flying with another pilot, First Lieutenant John Conlon, to a neighboring bas

For 40 years that was the last report the Montgomery woman received about her husband. Then earlier this year, the phone rang.

When she found out that her husband’s plane and some of his effects personal items had been located, her first emotion was relief.

“After so many years, I had no hope that he was still alive,” she said. “We had already had the funeral at Arlington. We had said our good-byes. We knew he wasn’t coming back.

“But while I realized he must have died, it was hard not to worry about how it might have happened. You’d hear stories about people who were captured and tortured, and you’d just pray that nothing like that could have happened. Knowing that it hadn’t, that it had been quick, was a relief.”

Claire Evans, Conlon’s sister who lives in Dallas, Pennsylvania, agreed.

“That was the worst part of not knowing — not knowing how they died, whether they’d spent years as POWs or been tortured,” she said. “No matter how horrible it was that they died, and it was horrible, it was a huge relief to know that it hadn’t been something where their suffering had gone on and on.

“I’m just so appreciative to our government, that 40 years later, they were still looking for our people. It’s such an American thing. I don’t think any other country in the world would be spending so much effort to bring their soldiers home.”

Ann Andrews said she, too, is grateful that she and the couple’s two children, Jenny and Sandy, finally know what happened all those years ago.

March 4, 1966

It was 3:20 p.m. when Stuart Andrews took off in his Cessna O-1E Bird Dog.

The Bird Dog was a dangerous plane to fly in combat — a light, slow, single-propeller airplane that could be brought down by small-arms fire. The planes were used for everything from transporting passengers and light cargo to reconnaissance and aerial photography.

Andrews’ assignment was more dangerous. His job was to swoop down on enemy troop movements and fire flare-like rockets to help guide fighters and bombers to their targets.

But when he took off from Qui Nhon Air Field in South Vietnam’s Binh Dinh Province, he wasn’t on a dangerous mission. This was as close as it came to a day off.

Andrews was going to visit friends at Cheo Reo, an outpost about 60 miles southwest, and volunteered to do reconnaissance along the way. Conlon, a pilot who usually flew F-4C Phantom bombers, volunteered to go with him to get additional training in the smaller plane.

But wars have no off-days.

About 30 minutes into the flight, Andrews was asked to make a detour to check out sightings of camp fires that indicated “suspected enemy locations.” His confirmation of the request was the last contact with the plane.

By 5:45 p.m., it was declared missing, and a search began.

During the next six days, there were 123 sorties — a total of 286 hours and 20 minutes of flying time — to help the 95 soldiers on the ground locate the pilots.

It was to no avail. The search was called off at 7 a.m. March 10, 1966.

Honors but no answers

It was not until December 1, 1977, that Andrews’ status was changed from missing in action to killed in action. “No information pertaining to him has ever been obtained from any other official or unofficial source,” the declaration stated.

Despite a lack of remains, he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery on June 13, 1978, and that same year, his name joined a list of 33 Yale graduates on a memorial tablet at the university, honoring those who died in the Vietnam War.

There were plenty of other honors, including an airfield in South Vietnam named for him. But what impressed Ann Andrews the most was how many had searched for her husband and for how long.

Before going to Vietnam, the 37-year-old veteran of the Korean War had been aide de camp to General P.D. Adams, while he formed America’s first Strike Command at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida.

She wondered if that had influenced the length of the search.

She had no idea that the search had not actually ended or how long and extensive it would become.

‘Looking for a tooth in the jungle’

The Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command’s mission is to find and identify Americans from past wars, and it has found and identified more than 1,200 of them.

JPAC, which has its headquarters at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii, has the largest anthropological skeletal laboratory in the world.

It also has 425 employees, including more than 30 anthropologists and archeologists, and an incredibly tough job.

“In many cases, it is literally like looking for a tooth in the jungle,” said Rumi Nielson-Green. An Army major, she said to simply call her a “spokeswoman” because JPAC isn’t an Army project, but a project run by all four major military branches along with civilian Department of Defense workers.

“It is very daunting work, but we average about two people each week that we are able to find and identify, and we know that each name we can place on the board is a family that finally got an answer.”

It’s hard work, and she said it is getting harder as years pass and eye-witnesses become fewer.

“The cases become harder and harder to resolve,” she said. “Many involve high-speed crashes or high-temperature burns, and many involve instances where villagers may have buried someone and then over the years moved away or died.”

Skill, hard work and luck

The case of Andrews and Conlon involved a high-temperature crash and a nearly forgotten burial, but JPAC had both skill and a little luck.

In August 2005, a villager in the Gia Lai province told JPAC a single-propeller plane had crashed nearby. Information led JPAC to believe it could be a U-6A Beaver, a rugged cargo plane that could land and takeoff almost anywhere, that had disappeared in 1971.

On February 6, 2006, a JPAC team began an archeological dig after hearing reports of villagers burying two men from the crash.

Much of the evidence was wrong — the dates, the size of the plane, the location of the grave. But a crash had occurred, and the team found the site, small items from the plane and what appeared to be remnants of a shallow grave.

“We have experts at the dig who specialize in military materials, experts who can look at a zipper and tell you not just that it is from the left leg of a flight suit, but what years that type of suit was made,” Nielson-Green said.

The more than 50 pieces of “supportive evidence and materials” indicated the plane was an O-1 Bird Dog.

But the key evidence from the three-week excavation required little expertise — a metal military ID bearing the name Stuart M. Andrews.

Because the grave was shallow and dug in what the report called “an erosion area,” searchers found only four teeth, but an expert at Hickam AFB was able to identify them as Conlon’s.

Leave no one behind

Sandy Andrews, who lives in Cocoa Beach, Florida, where he is involved in resort development and management, said he was impressed with what JPAC did to find his father until he found out the details.

Then he was more impressed.

“When I heard what they had done, I was thankful,” he said. “You have to appreciate people who will go all over the world and dig in jungles to try and find American servicemen and bring them home.

“Then I saw pictures of the dig, and it was a much, much larger area than I had imagined. They cleared this huge portion of jungle and then carefully went through it. It is the whole concept of ‘leave no man behind.’ I think it is something that makes you proud of America and to be an American.”

A painful healing

Intellectually, Jenny Andrews had come to terms with her father’s death decades ago. A partner in a Fort Worth, Texas, law firm, she was only a child when he disappeared.

“There are some families who still expect that 40 years later, their missing relative will suddenly walk out of a Vietnamese jungle somewhere. That isn’t us,” she said. “Still, when mom called in May with the news, my legs just gave way.

“Although you may have accepted what happened and that one day the news will come, you still aren’t necessarily prepared for it. Unfortunately, the news came within a week and a half of my husband passing away. It felt like I had been squashed and then a week and a half later had been squashed again.”

Evans, Conlon’s sister, reacted much the same way.

“It was a relief and yet a dreadful shock at the same time,” she said. “I never expected the emotion that I felt when I got that phone call. I mean I was shaking.”

Still, as hard as it was to hear the information, not hearing it had been infinitely harder, Jenny Andrews said.

“It was painful to hear it, but it is better to know. And I’m grateful to the government for carrying on the search so that we weren’t just left in a limbo, that void where you just don’t know,” she said.

“It was like your whole world shook and then resettled, but then you thought OK, at least now, we definitely know what happened.”

And like her mother, even in the terrible news, Jenny Andrews was able to find something for which she could give thanks.

“It helped me finding out that the villagers actually took the care to bury their bodies instead of them just being left out there,” she said “My father and his colleague were given burials and treated like human beings, and for that, I’m grateful.”

Evans will bury her brother’s remains at Arlington Cemetery next month.

She said she is doing it for her children, one of whom is named John Conlon Evans after her brother, and for their children.

“When I got the news, I found myself thinking this is awful,” she said. “But it isn’t because at least now there is closure, and in my heart, I have the feeling that they have finally come home.”

Missing U.S. pilots’ grave found in Vietnam after 40 years

15 September 2006:

A Montgomery, Alabama, woman whose husband’s military ID was recovered from a shallow grave in Vietnam after 40 years said she’s relieved to know he had not been captured and tortured during the war.

“After so many years, I had no hope that he was still alive,” Ann Andrews said.

The Defense Department in May informed her that Air Force Major Stuart M. Andrews and a co-pilot apparently were buried by villagers after a plane crash.

Andrews, 37, took off from Qui Nhon Air Field in South Vietnam’s Binh Dinh Province on a reconnaissance flight in a Cessna O-1E Bird Dog on March 4, 1966, flying with First Lieutenant John Conlon. They never returned.

Despite a lack of remains, Andrews was buried at Arlington National Cemetery on June 13, 1978, and that same year, his name joined a list of 33 Yale University graduates on a memorial tablet at the university, honoring those who died in the Vietnam War.

The pilot’s family anguished for years about how he died.

“You’d hear stories about people who were captured and tortured, and you’d just pray that nothing like that could have happened. Knowing that it hadn’t, that it had been quick, was a relief,” Ann Andrews told the Montgomery Advertiser for a story Friday.

Claire Evans, Conlon’s sister who lives in Dallas, Pennsylvania, agreed.

“That was the worst part of not knowing – not knowing how they died, whether they’d spent years as POWs or been tortured,” she said.

The grave was discovered after military officials followed up on a tip in August 2005 from a villager in the Gia Lai province about a plane crash.

On February 6, 2006, investigators from the Hawaii-based Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command began an archaeological dig after hearing reports of villagers burying two men from the crash.

They found a metal military ID bearing the name Stuart M. Andrews.

Because the grave was shallow and dug in what the report called “an erosion area,” searchers found only four teeth, but an expert at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii was able to identify them as Conlon’s.

Evans plans to bury her brother’s remains next month at Arlington. She’s doing it for her children, she said, one of whom is named John Conlon Evans after her brother, and for their children.

“When I got the news, I found myself thinking this is awful,” she said. “But it isn’t because at least now there is closure, and in my heart, I have the feeling that they have finally come home.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard