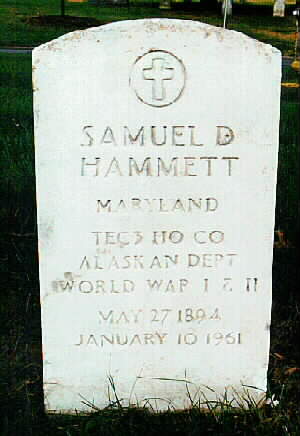

Born on May 27, 1894, he was a veteran of World War II, serving as a Sergeant in Alaska.

He was a prolific writer, being the author of the “Sam Spade” mystery novels. He was a member of the Civil Rights Congress, a liberal political group which was targeted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) as being a Communist front. He refused to name contributors to the organization and was sentenced to six months in jail for that refusal.

He later became a virtual recluse in the tiny village of Katonah, New York, partly due to chronic health problems.

He died there on January 10, 1961 and, as was his wish, he was buried in Section 12 of Arlington National Cemetery. At one point, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover attempted to block the burial but was overruled in that attempt.

Sam Spade at 75

“The Maltese Falcon” celebrates its diamond anniversary.

BY TOM NOLAN

Thursday, February 10, 2005

The Pulitzer Prize for the best novel published in America in 1930 went to a book by Margaret Ayer Barnes titled “Years of Grace.” But it was quite a different 1930 novel that would enter American cultural folklore and remain in print into the 21st century.

February 14, 2005, marks the 75th anniversary of the publication of Dashiell Hammett’s “The Maltese Falcon”: that riveting tale involving a San Francisco private detective named Samuel Spade and a diverse crew of miscreants, all in search of a coveted 16th-century statuette. The anniversary will be commemorated, this month and next, by lectures, exhibits, and celebrations at the Library of Congress in Washington (near Hammett’s Maryland birthplace, and his Arlington National Cemetery grave), and in San Francisco, where the story was written. And the novel is available from Vintage/Black Lizard in a newly packaged trade-paperback edition (as are two other Hammett books, and a new anthology, “Vintage Hammett”).

Thanks in part to the equally classic 1941 John Huston film starring Humphrey Bogart, the tale of the Falcon and the character of Spade have become embedded in popular myth. “It’s taken on a life of its own,” says Hammett biographer and scholar Richard Layman. “There’s a nursery in Montana called Sam’s Spade. There’s a piece of antispam software called Sam Spade. ‘Sam Spade’ means something to people who maybe don’t even know that there was a novel written by Hammett.”

As for that novel, its critical reputation continues to grow. Hailed on publication by such influential reviewers as Dorothy Parker and Alexander Woolcott, “The Maltese Falcon” in time earned praise from such European novelists as André Malraux and André Gide. Hammett’s prose was compared favorably to Hemingway’s, and it was reported in the press, circa 1930, that Dashiell Hammett was a contender for the Nobel Prize. “The Maltese Falcon” has been published in 76 foreign editions in 30 countries. In 1998, the board of the Modern Library named it one of the best hundred novels written in English in the 20th century.

“It is an American classic without qualification,” says Prof. Layman, who will give the Library of Congress talk on “The Maltese Falcon” on February 15. “The novel is ‘a ripping good yarn,’ on the one hand; on the other hand, it’s a book that can be held to the highest literary standards and acquit itself well.” The book broke fresh ground, he says. “That sort of hard, individualistic attitude of Sam Spade was something that I think was brand-new: an innovation of Hammett’s. And that use of indirect third-person narration, to achieve what Hammett was looking to achieve, is very skillfully done. . . . He was proud of it, I think. When he submitted it to Knopf, he said words to the effect of: ‘I’ve got this one right, you guys; don’t fiddle with it!'”

No matter how high its literary standing, “The Maltese Falcon” will always be a most subjective pleasure for one particular reader: its author’s only surviving child, Jo Hammett Marshall.

“I suppose I first read the Falcon when maybe I was nine years old or something,” says the 78-year-old Mrs. Marshall, author of the memoir “Dashiell Hammett: A Daughter Remembers” (2001). “I love it, and I’ve reread it over the years. But . . . I keep mixing up Spade’s voice and the narrator’s voice sometimes with my father’s. I know this isn’t kosher, this isn’t how you’re supposed to read books! But in a way it’s kind of interesting, because so much of the dialogue–well, particularly Spade’s — sounds like something my father might say in a similar situation. I was thinking about the bit where he tells Brigid that he’s sending her over, and he hopes they won’t hang her, she’s got such a pretty little neck–but he’ll always remember her! I can’t quite picture my father being in that kind of circumstance, but if he were–that’s what he’d say!”

Jo Marshall will be in attendance on March 19, when the building at 891 Post Street in San Francisco where her father lived when he wrote “The Maltese Falcon” (the author modeled Spade’s apartment on his own) is designated a National Literary Landmark under the auspices of Friends of Libraries USA.

That residence (whose tenant, a Hammett fan, keeps it up in appropriate style) has been toured often by another unique Falcon devotee: the author’s granddaughter, Julie M. Rivett.

“One of the things that I like about my connection to the book,” says Mrs. Rivett (co-editor, with Prof. Layman, of “Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett”), “is being able to visit that space and see how my grandfather lived, and how he would have almost blocked out how Spade would have moved around the apartment. To me, those scenes make more sense when you realize exactly how they were laid out.”

Julie Rivett and Richard Layman have co-curated an exhibit on “The Maltese Falcon,” at the San Francisco Public Library through March 31, that includes American and English first editions of the novel, period photographs, and items indicative of the book’s permeation of the culture: comic strips, radio shows, even a Sam Spade alarm clock.

“There’s so much to [the novel],” Mrs. Rivett says, “so many different ways to look at it, and different layers and angles that you can approach it from.” In her current rereading of “The Maltese Falcon,” she says, it’s the author’s “hyper-specificity” she’s paying special attention to: “Those really detailed descriptions, painting this physical picture. But I think it’s like a magician’s sleight-of-hand: You’re looking at this–but you’re not seeing the other, the thing behind it, which is completely different.”

Even after 75 years, it seems, there is no end of appreciation (and no shortage of readers) for this singular work called by Ross Macdonald “the best mystery ever written”–a story so complex, he thought, “you can go on rereading it and finding things in it for the rest of your life.”

Dashiell Hammett: The man, the mystery

By Scott Eyman

Palm Beach Post Books Editor

Sunday, February 13, 2005

As is so often the case, Raymond Chandler said it best, and with a becoming generosity: Dashiell Hammett “did over and over again what only the best writers can ever do at all. He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before.”

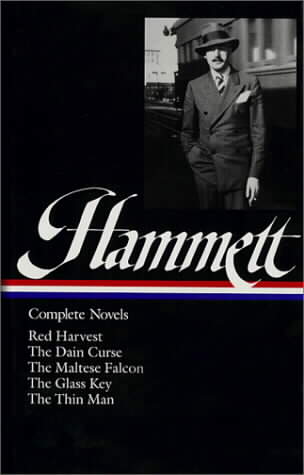

Hammett’s ouevre is thin but lasting: five novels published in six years (Red Harvest, The Maltese Falcon, The Dain Curse, The Glass Key, The Thin Man) and six dozen short stories.

The Maltese Falcon, celebrating its 75th anniversary this month, isn’t Hammett’s best book — that would be Red Harvest. But it’s his most influential, and, because of the Humphrey Bogart film, his most famous.

It’s the story of private detective Sam Spade and his encounters with a trio of hard-boiled thieves searching for a jeweled statue of a black bird. It may be one of the most imitated novels of the 20th century — the template for every story involving a tough, wisecracking private eye entangled with a devious, alluring woman, and now-stock characters like the doll-face secretary and the gunman with heaters bulging beneath his trench coat.

(Red Harvest has also been imitated to death. The plot — an amusingly cold-hearted mercenary comes into a town riven by rival gangs and sets them against each other — has been plundered in dozens of novels and at least that many movies, notably Akiro Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars.)

The Maltese Falcon was made into a movie twice, in 1931 and 1936, before director John Huston did it right in 1941. The physical and verbal perfection of Huston’s adaptation was helped immensely by the fact that he used Hammett’s dialogue almost exclusively.

Viewed from the standpoint of literary history, Hammett’s great accomplishment was creating the first detective with what would now be termed situational ethics. Spade had no compunctions about having an affair with his partner’s wife — the lady was willing and he didn’t like his partner all that much — but when his partner is killed, he is determined to find out who did it.

In other words, Spade is a hard, shifty man, but he has a code.

“Hammett is a must-read for anybody writing a crime novel,” says Michael Connelly, author of such bestselling novels as The Poet and Blood Work. “You can trace the evolution of the form through his work. Chandler credited Hammett with taking the mystery out of the drawing room and putting it out on the street where it belongs. I think if Hammett had not done that, I might not be doing what I do.

“To me, Hammett is very gritty and tough, unsentimental and journalistic in his writing. And that is what drew me to the genre. The idea of writing about characters facing evil in its many forms and making tough and sometimes violent choices. The devil doesn’t sit around drinking tea in the drawing room. Hammett knew that.”

Hammett looked like his writing. Tall (6-1 and a half), lean, with a thick crop of prematurely white hair and a dark mustache, he constructed both his life and his work with a terseness and objectivity unusual even among his contemporaries.

He’s an unindicative writer — not a lot of adverbs.

Eight years with Pinkerton

Samuel Dashiell Hammett was born in February 1894. He left school at 13 and worked at the usual succession of low-end jobs until latching on as a detective with the Pinkerton Agency, where he stayed for eight years. Among other cases, he worked on the defense for silent film comedian Fatty Arbuckle’s rape trial.

After leaving Pinkerton’s, he worked in advertising, then served as a sergeant in the ambulance corps in World War I, where he contracted tuberculosis. There was a marriage, in 1920, to Josie Dolan, his nurse in the tuberculosis ward. They had two daughters, after which Hammett was sidetracked by a recurrence of the disease.

He got a Mexican divorce in 1927, by which time he had begun to forge a reputation as one of the main contributors to Black Mask, the primary detective pulp magazine of its era. Most of Hammett’s stories featured a nameless character known only as the Continental Op (Continental for his detective agency, Op for operative).

At first he used the pen name Peter Collinson, a variation on Peter Collins, which was underworld slang for a nobody. It was a direct statement of the alienation and emotional detachment that marked his life as well as his work.

Hammett’s great gift was clarity. He saw criminals and detectives as they really were. And yet his work transcends his background. Lots of cops write books, but none of them have written with anything near Hammett’s level of style.

Mystery historian Bruce Murphy wrote that Hammett “was not minimalist, because minimalism is a conscious reaction to some other literary convention perceived to be wordy and overwritten. Hammett was not so much naturalistic as simply natural.”

Some of Hammett’s early stories are rough — guns are always blazing, because in the Black Mask aesthetic, the reader had to be held with either the threat of action or the action itself. But they weren’t that way for long.

Hellman shaped our image of him

The image we have of Hammett largely derives from playwright and memoirist Lillian Hellman, his lover of 30 years. She wrote about him obsessively in her old age in such books as Pentimento and portrayed his early marriage as a youthful mistake obliterated by his great love for Hellman. She also implied that he happily diverted his creative energies to mentoring her own career.

Julie Rivett, Hammett’s granddaughter, regards Hellman’s portrait as “a distortion of the truth. There were five years between the two children. Within that time frame, it was a normal life.

“By the time my mother was born, the TB had recurred. But the public health nurses told my grandmother not to live with him. He visited them every weekend, he would draw pictures for the girls. He was a part of the family. It wasn’t Norman Rockwell, but he maintained a relationship.”

After The Maltese Falcon in 1930, Hammett published The Thin Man four years later. It’s a lighter book, largely because it was written in the first flush of his affair with Hellman. Heavy drinking and hints of adultery permeate the novel, and the characters are more memorable than the mystery.

They’re also a pretty reliable indicator of the Hammett/Hellman relationship, which lasted in spite of serial infidelities on both their parts. (Hammett didn’t particularly care who Hellman slept with, but Hellman was jealous and he gave her a lot to be jealous about.)

The Thin Man also gave Hammett a great deal of fame and money, because of the movies starring William Powell and Myrna Loy. The characters Nick and Nora Charles — also highly imitated — were different than his earlier detectives. They created an image of marriage as a duel of wits between equals and a great deal of fun, provided you don’t lose your sense of humor.

In the book, Nick Charles is a tough ex-detective keeping a wary eye on his rich wife’s money, whereas Powell’s suavity and charm make the idea of an occupation ridiculous; he couldn’t care less about money as long as there’s enough for the next bottle of gin.

Nothing for last 25 years of life

After The Thin Man, Hammett stopped publishing. He worked desultorily on stories for a couple of Thin Man movies, but for the last 25 years of his life, there was basically silence.

Writers who stop writing are an interesting area of inquiry (see Salinger, J.D.) Of course, drinking the way Hammett did can be a full-time occupation, but he had been doing that while blasting through his novels and it hadn’t slowed him down.

On the other hand, five high-quality novels are more than most writers produce in 30 years of work. It’s possible that he burned out and, unlike most writers, knew it.

“He didn’t entirely stop,” says his granddaughter Rivett. “He kept trying; he wanted to write something in the mainstream that was good. He started a novel called Tulip, gave it up, then abandoned another book My Brother Felix. He wanted to write a good book too badly, and would kill it because it didn’t live up to his standards. Also, the creative urge can be expressed in different ways. If he wasn’t expressing it in writing, he was expressing it in working with Hellman, or in his political activities.”

She said Hammett wanted to be more than a genre writer. “In the archives, there’s a short story, and when I started reading this story I realized it was the beginnings of My Brother Felix. I gave it to (Hammett’s biographer) Rick Layman. ‘It’s Watch on the Rhine,’ he said. My grandfather gave it to Hellman and she developed it into (the play) Watch on the Rhine. It’s the same story.”

A Marxist and a patriot

Another possibility: Hammett was a Marxist, maybe a member of the Communist Party. Money didn’t sit well with him, so he began to give it away in the manner that seemed most efficient.

“He was part of a generation that could be both a Marxist and a patriot and there was no conflict in his mind,” says Rivett. “He was doing what he thought best for his country; he was a sincere patriot.”

His granddaughter makes pains to point out that Hammett was not identical to Sam Spade.

“He had a very sentimental streak; he loved dogs and babies and was very loving and indulgent with his daughters, in his way. When my mother got married, he came home, stayed at the house and gave her away. When they were little, he would send them huge boxes of toys, and very funny letters. When I read him, I see his sense of humor, the wisecracks of Spade, or the Op.”

When World War II broke out, the 47-year-old tubercular writer somehow convinced the Army to let him enlist as a private. Serving in the Aleutians, he edited a newspaper and helped write and edit a history of that theater.

So far, so good. But after the war, he served as trustee of a bail fund for four Communists. The four jumped bail and Hammett was left holding the bag. He refused to name who had contributed to the fund and served five months in jail in 1951.

The Red Scare period also killed off the long-running Sam Spade radio show, destroying Hammett’s source of income. “He supported my grandmother until the 1950s when he couldn’t anymore,” says Rivett. “And he put my mother through UCLA. There were times when he was late, or when he was drinking, but he was their main source of income. After his money dried up, my grandmother had to go back to nursing. ”

Hammett spent the last 10 years of his life being nursed by Hellman on her small farm. The tuberculosis from his service in World War I had been complicated by emphysema from his service in World War II. His health got so bad that he gave up drinking. Although he did not or could not write, he read everything, from glassmaking to philosophy to mathematics.

Hammett the real deal

Now, there are writers who write tough but are far from tough themselves — fellow mystery novelist Chandler was a fairly sodden alcoholic with a sticky devotion to a wife who was more like a mother.

But Hammett was the real thing. As things went permanently south, he took what life dished out and kept going, never asking for quarter, never expecting any. He not only wrote like an authentic existentialist, he acted like one as well.

“I met him in 1960,” remembers his granddaughter. “He was very ill, so Lillian Hellman called and told us we had better come. He had lung cancer, and his heart was failing. We flew to Martha’s Vineyard, spent a week with him and Hellman.

“I remember little snippets, echoing noises and big dogs, standard poodles. They raised beautiful standard poodles. Hellman tolerated us; I think she preferred the dogs. But my grandfather had a great time with us. I have a very specific memory of him teaching me to hold dog food in the flat of my hand to feed one of the poodles. I was scared, because standard poodles are big to a child, but he had me hold the food like you hold an apple for a horse, with the fingers curved away from the palm. And the poodles took it very gently.

“He was great with kids, actually.”

When he died in 1961, his ex-wife’s first thought was to go to the funeral, but her daughter talked her out of it. “But I’m his wife,” she said. She didn’t go, but to her dying day Josie regarded herself as Mrs. Dashiell Hammett.

Hammett was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. When he died, he owed something like $160,000 in back taxes, or so the IRS claimed. “It was the downstream of the McCarthy era,” says Rivett. “If they couldn’t get you for anything else, they sent the IRS.”

Hammett’s only assets were his copyrights, but everything he had written was out of print. Hellman put them up for auction, and cut a deal with the IRS that they’d accept whatever money they brought as full payment for the debt.

In 1961, the price for everything Dashiell Hammett ever wrote was $5,000.

They’re worth more than that now, not that any monetary figure could ever compensate for a life spent in quiet rebellion against the American grain.

HAMMETT, SAMUEL D

- T/3 HQ CO, ALASKAN DEPT

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF BIRTH: 05/27/1894

- DATE OF DEATH: 01/10/1961

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 01/13/1961

- BURIED AT: SECTION 12 SITE 508

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Writings On Samuel Dashiell Hammet

May 1994:

“Samuel Spade’s jaw was long and bony, his chin a jutting v under the more flexible v of his mouth. His nostrils curved back to make another, smaller, v. His yellow-grey eyes were horizontal. The v motif was picked up again by thickish brows rising outward from twin creases above a hooked nose, and his pale brown hair grew down – from high flat temples – in a point on his forehead. He looked rather pleasantly like a blonde Satan.” – from Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon.

Samuel Dashiell Hammett is one of the few men who can be said to have invented an entire literary genre. That, as well as the fact that this year marks the centennial of his birth, is sufficient cause for a reappraisal. His books have never been out of print, and they have a way of remaining evergreen, of repaying occasional visits. In line with that, Vintage has attractively repackaged all the Hammett titles. Not to be blunt about it, they deserve a space on every library shelf, for, at their best, they are paradigms of a very American manner of writing, of seeing the world. Indeed, to read Hammett again is to touch the wellspring, not merely for the hard-boiled detective novel, but a very specific kind of American character. Hemingway might have come first, but not by much.

Hammett’s terse, flat, unindicative writing evolved quickly from the slightly florid short stories that he began writing in the early ’20s for Black Mask magazine. Before Hammett, popular detectives were very much in the mold popularized by S.S. Van Dine, creator of that insufferable know-it-all Philo Vance, who tended to gather the suspects into the mansion drawing room to hear Vance proclaim “The butler did it.” The lean, mean Hammett gave murder back to the common people, who do it best. Hammett’s writing career was very short, extending for little more than 10 years. He wrote almost nothing after 1934, preferring to spend his time drinking, arguing with his lover, Lillian Hellman, and nursemaiding her writing career. A frenetic start, then nothing. In the space of 4 years, Hammett wrote 6 novels. Then, almost nothing.

The Thin Man (1934) was the last of Hammett’s novels, and there is a noticeable falling off. Although the central characters are a delight, the book has no threatening resonance, no aftertaste, as all his previous novels do; the plot is just a puzzle, and not a particularly interesting one at that. Because the book, and, especially, the William Powell-Myrna Loy movies were so successful, Hammett, like the agreeably alcoholic Nick Charles, could afford to sit back and relax.

Other than writing a few synopses for movie sequels, the only real writing Hammett did for the rest of his life involved signing his name on the back of checks. Unlike the vast majority of detective writers, Hammett wasn’t fantasizing about the Continental Op or Sam Spade or The Thin Man’s elegant Nick Charles. He had been a Pinkerton detective for 8 years, and, more importantly, was every bit as tough as his characters. Comparisons to that sodden Momma’s boy – if superior novelist – Raymond Chandler are instructive. In Hammett’s work, sentiment is extinct, and innocence is long since lost. There’s no begging, not from the author, not from the characters. Sam Spade is rough and lacking in charm, a negative man that Hammett casts in a positive role. Films keep his work alive. Strictly speaking, Hammett’s best work is Red Harvest and The Maltese Falcon. Oddly, the former has never been filmed, although Bernardo Bertolucci talked about doing it for years, with Marlon Brando. However, the plot mechanics, if not the atmosphere, have been so ruthlessly plundered by other films – most prominently Yojimbo and A Fistful of Dollars – that it might seem like a twice-told tale if it ever does get made. Part of the reason Hammett has maintained his popularity are the films made from his work. In particular, John Huston’s film of The Maltese Falcon is a near-perfect transposition, with the writer/director faultlessly capturing not merely the tone, but the look of the characters: Bogart’s saturnine, harsh Spade, and Peter Lorre’s effeminate boytoy for Sidney Greenstreet’s looming Caspar Gutman.

A writer as fiercely controlled, as glamorously self-destructive as Hammett can make critics gush like adolescents at a rock concert; one has written that Hammett’s treatment of San Francisco in The Maltese Falcon as “one of the great literary treatments of a city,” right up there with Joyce’s Dublin or Dickens’London. Well, maybe, except that Spade doesn’t have to exist in San Francisco in the sense that Sherlock Holmes has to exist in London. It’s enough to echo Raymond Chandler, who was a good critic as well as a good writer. He wrote that Hammett “wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before.” Hammett the man was of a piece with his furtive, devious, almost unknowable main characters.

When WWII broke out, the 48-year-old alcoholic enlisted, convincing the doctors that the tuberculosis scars on his lungs – contracted during svce in WWI – were of no account. After the war, with Roosevelt dead, the witch hunters closed in and persecuted Hammett for his left-wing politics, shortly after a particularly bad case of the dt’s caused him to quit drinking.

In front of a Congressional committee, he was asked to name contributors to a bail fund for Communists, for which he was a trustee. He flatly refused and was sent to prison for 5 months. The government then proceeded to sue him for back taxes and won a judgment of $140,000, in effect bankrupting him. As his always shaky health spiraled down, he took it stoically, without complaint. He died in 1961 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

As Stephen Marcus writes in his introduction to The Continental Op, “He had served the nation in two World Wars. He had also served it in other ways, which were his own.”

Born: St Mary’s County, Maryland, May 27, 1894, died January 10, 1961, he was an American crime novelist whose realistic style and settings created a new genre in mystery fiction. After working as a Pinkerton detective for 8 years, he began publishing stories in Black Mask magazine after 1923. His first 4 novels–Red Harvest (1929), The Dain Curse (1929), The Maltese Falcon (1930; film, 1941, with Humphrey Bogart), and The Glass Key (1931; films, 1935 and 1942)–greatly influenced American thought and writing. His Continental Op, the anonymous narrator of the first 2 books, and Sam Spade, the leading character of the third, became models of the hard-boiled private detective: unsentimental, making no moral claims, but bringing a ruthless honesty and dedication to the job. His last novel, The Thin Man (1934), introducing the sophisticated husband-and-wife sleuthing team of Nick and Nora Charles, became an enormously successful film (1934).

He also did some screenwriting but was handicapped by a serious drinking problem and by being blacklisted for his left-wing political affiliations after 1951. Parts of an unfinished autobiographical novel were published as The Big Knockover and Other Stories (1966), edited by Lillian HELLMAN, his friend and companion of 30 years. Hammett’s The Continental Op (1974) was also published posthumously.

Dashiell Hammett: A Daughter Remembers

DASHIELL HAMMETTA Daughter Remembers By Josephine Hammett. Edited by Richard Layman and Julie M. Rivett Carroll and Graf. 176 pp. $30.

DASHIELL HAMMETT Crime Stories and Other WritingsEdited by Steven MarcusLibrary of America. 934 pp. $35

Most novelists lead insular and unexciting lives. Not so Dashiell Hammett. Born in St. Mary’s County, Md., in 1894, he was a World War I veteran and Pinkerton operative by the time he began writing detective stories for the fabled Black Mask magazine in the 1920s. In a short period, he penned five popular and critically acclaimed novels, some of which were constructed on variations on his serialized stories. His appearance — tall, rail-thin and urbane, with a shock of prematurely white hair — was striking, undoubtedly contributing to his celebrity status.

He is credited with creating the tough, unsentimental and reportorial style of fiction known as hard-boiled. Never mind that hard-boiled pulp practitioners like Carroll John Daly had preceded him in Black Mask, or that Hemingway was developing his own brand of muscular, rhythmic, stripped-down prose at the same time. Hammett wasn’t the first realist in crime fiction, but he was the first to bring it up to the level of violent art.

By 1934 his career as a novelist was done. Though he continued to write screenplays, criticism, comic strips and radio scripts, he never published another novel in his lifetime. “I stopped writing because I was repeating myself,” he claimed. “It is the beginning of the end when you discover that you have style.”

He married young and fathered two daughters but left them early on, carrying on with longtime lover Lillian Hellman (and others), living in a Nick Charles haze of New York nightlife, hotel apartments, room service and booze. Throughout the ’30s, he was involved in anti-fascist and Marxist organizations but was also an avowed patriot. He re-enlisted during World War II and spent those years serving in the Aleutian Islands, working on an Army newspaper.

In 1951, Hammett was found guilty of contempt of court after refusing to testify against communists convicted of Smith Act violations; he did six months time in a federal prison. In ’53 he was summoned to Washington by Sen. Joseph McCarthy, who asked him during testimony if the government should fund purchases for library books written by avowed communist sympathizers. To a visibly confused McCarthy, Hammett replied, “If I were fighting Communism, I don’t think I would do it by giving people any books at all.”

By now his novels were out of print, his radio shows had been canceled, and the IRS had taken what little he had for back taxes, leaving him impoverished. He had a respiratory disease going back to his first stint in the service, exacerbated by his prodigious cigarette intake, and his health rapidly declined. He died of lung cancer in 1961. Hammett was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, where he rests among his fellow soldiers.

All of this is recounted in Dashiell Hammett: A Daughter Remembers, written by his youngest child, Josephine. Her memories are more like snapshots of recollection, as her father was an absent but strongly imagined presence for most of her life. In the book’s introduction, she herself admits that “It is not a biography. . . . It is not true. But it is as true as I can make it.” Still, a sharp picture of the man does begin to develop as the memoir progresses. This is due in part to Josephine Hammett’s clear, controlled style, and her critical but loving assessment of her father. She is also surprisingly objective about the women in his life,

including her mother, the actress Patricia Neal, and the easy-to-hate Hellman. With many rare and telling photographs included, this is a good overview of the man and the author, and a treat for Hammett completists.

For those interested in the work itself, there is Hammett: Collected Stories and Writings, recently published by the Library of America. The Continental Op stories are reprinted here in their original Black Mask format, as are key non-Op stories like “Nightmare Town,” an early draft of a novella that became The Thin Man, a complete Hammett chronology and detailed notes. All save three of the stories are readily available in other collections, but they have never been packaged as handsomely.

Hammett aficionados claim that his short fiction — intricately plotted detective procedurals heavy on street slang and physical action — represents his finest work. But, read in succession, these stories have a sameness, and Hammett’s aversion to emotion and his now antiquated style render them somewhat dry today. The novels — with the exception of The Dain Curse (an unwelcome infusion of “weird” pulp tradition) and The Thin Man (an entertaining trifle) — are the place to start. Red Harvest, inventive in its use of language and amped-up mayhem, is the grandfather of all hardboiled detective fiction, and best represents Hammett’s ongoing fascination with the abuse of power and the absence of a moral center in a world gone wrong. The Maltese Falcon, with its infamous thieves’ gallery — Casper Gutman, Joel Cairo and Brigid O’Shaughnessy among them — and its (seemingly) amoral antihero, “blond Satan” Sam Spade, is perhaps the most enduring mystery of its kind. Finally, there is The Glass Key, his masterwork, a meditation on male friendship, loyalty and human politics, and one of the very best American novels written in the last century.

My advice is to separate the man from the books, then read the books. In the face of all his accomplishments, I am uninterested in whom Dashiell Hammett slept with, or how much he drank, or what kind of card he carried. He invented an entire genre of literature, as unique to this country as blues and jazz, and just as lasting. Raymond Chandler said that Hammett “did over and over again what only the best writers can ever do at all. He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before.” What

a legacy.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard