From a contemporary press report

Robert W. Komer, 78, a hard-driving Army and CIA veteran who was one of the principal U.S. officials sent to Saigon in the 1960s to try to make a success of the nation’s commitment to the war in Vietnam, died yesterday (April 9, 2000) at Arlington Hospital after a stroke. He lived in Arlington.

Mr. Komer–known as “Blowtorch Bob”–was sent to Saigon in 1967 by President Lyndon B. Johnson to run the pacification program, described as the battle for the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people.

The assignment was to run in parallel with the strictly military U.S. effort and was close to Johnson’s heart. The year before, Johnson had named Mr. Komer a special presidential assistant to energize the so-called other war in Vietnam.

“He was about the best thing that had happened to the Vietnam war at that date,” former CIA director William E. Colby wrote in his 1978 memoirs.

Colby, who was later assigned to work for Mr. Komer, acknowledged that Mr. Komer had been called “brash, abrasive, statistics-crazy and aggressively optimistic.”

But he also found him “quick and intelligent,” above parochial interests and “fearless and tireless” in seeing to it that military and civilian bureaucracies did what was needed.

After receiving the 1966 assignment, Colby wrote, Mr. Komer set about pushing the Vietnam experts in Washington to provide measurable goals and standards for achievement rather than broad philosophical theories about war aims. He resolved earlier conflicts, Colby said, by deciding that pacification should be under military authority but civilian direction.

The formal appointment Mr. Komer held was as Army General William E. Westmoreland’s deputy for civil operations and revolutionary development support (CORDS). Mr. Komer’s work during his tenure in Vietnam included modernizing and reequipping South Vietnamese territorial forces, and repairing the destruction left by the enemy’s 1968 Tet Offensive.

Johnson did not seek reelection in 1968, and before he left office, he recognized Mr. Komer’s long-standing interest in the Middle East by naming him ambassador to Turkey. He left Vietnam in November 1968, after, according to Colby, making “a

reality” of the pacification program.

CORDS has been associated in commentary on Vietnam with one of the most controversial programs of the war. In addition to winning popular loyalty to the United States and its South Vietnamese ally, officials wished also to root out Viet Cong loyalists. A plan for doing this–known as Phoenix–was put into effect after Mr. Komer had left, and questions were later raised about whether assassination was among its tactics.

Robert William Komer was born in Chicago, grew up in St. Louis and graduated from Harvard University, where he also received a master’s degree in business administration. During World War II, he served as a first lieutenant in Army intelligence in Europe and was awarded the Bronze Star.

He joined the fledgling CIA in 1947 and was later assigned to the National Security Council. His abilities impressed top officials in the Johnson White House, who began using him as an all-around trouble-shooter.

In the early 1970s, he worked on Vietnam issues in California for the Rand Corporation. He later worked for Rand in Washington on NATO matters. During the Carter administration, he worked in the Pentagon as undersecretary of defense for

policy. He later returned to Rand as a consultant on defense issues.

He held the National Medal of Freedom.

Fifteen years ago, he was interviewed for a retrospective article on some of the personalities linked to the war. With the benefit of hindsight, he said, “I would have done a lot of things differently and been more cautious about getting us involved.”

His marriage to Jane Komer ended in divorce. His second wife, Geraldine Komer, died in 1996.

Survivors include three children from the first marriage, Doug, of Annandale, Dick, of Falls Church, and Anne Komer of Boston; a sister; five grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

Robert W. Komer, a point man in the United States’ star-crossed campaign to win hearts and minds in Vietnam, died on Sunday after a stroke. He was 78 and lived in Arlington, Virginia.

During the war and after, Komer was known as Blowtorch Bob, a name given to him by Henry Cabot Lodge, the American ambassador in South Vietnam who had said (in so many words) that arguing with Komer was like having a flamethrower aimed at the seat of one’s pants.

Komer was indeed a man with a fierce mind behind a mild mien. With his owlish eyeglasses and briar pipe and his 15 years at the CIA, he came to President Kennedy’s National Security Council in 1961 as the model of what the novelist John le Carre calls an intellocrat.

In Washington, where information is power, secret information can be the means to great power. He wielded it like a weapon in Vietnam, where his job was to help win the war without firing a shot through a program known as pacification.

The idea of pacification was that the war could not be won solely with bombs and bullets. Control of the people of South Vietnam would be won from the Communists of the north village by village, hut by hut, by social and political means, with information and propoganda and the selective use of force, by South Vietnamese soldiers backed by American civilians.

In 1966, as the battle intensified, he became President Johnson’s special assistant for Vietnam, in charge of the political side of the war. He later told an interviewer that he had warned Johnson that he had no experience in such matters. “Well,” the president replied, “maybe what we need is some fresh meat.”

“That’s what he said,” Komer recalled. “Not fresh blood, but fresh meat.”

In 1967, Komer arrived in Saigon with the rank of ambassador and the title of chief of pacification, on paper the No. 2 American civilian in Vietnam, second only in rank to Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker. He reinforced his reputation as a man with a take-no-prisoners attitude, a deathless optimism that the war would be won, and a near-religious faith in the power of facts and statistics to help win it.

An aide to Johnson, John P. Roche, later noted that if Komer had been asked how many Vietnamese had not been influenced by Vietcong propaganda, he would have replied “in 13 hours and 20 minutes” with a top-secret cable for the president’s eyes only, “definitively stating: 2,634,201.11.”

Komer’s “sensitive antennae were tuned to Johnson’s desires,” said a leading historian of the war, Stanley Karnow, and Komer produced a steady stream of statistics-laden reports that supported the Johnson’s’ vision of a light at the end of the tunnel.

In one study, he stated with confidence that precisely 68 percent of South Vietnam’s 17.4 million people were “relatively secure.” In another, he said that as “slow, painful and incredibly expensive though it may be, we’re beginning to ‘win’ the war.”

Working closely with William E. Colby, the top man for the CIA in Vietnam, Komer led a village-by-village effort to win hearts and minds. The pacification program evolved into a more tough-minded project called Operation Phoenix. Conceived by the White House and supported by the CIA, Phoenix sought to expose Vietcong agents who were working in South Vietnam. Colby later testified that Phoenix killed 20,587 Vietnamese.

In October 1968, Johnson named Komer ambassador to Turkey. His tenure was short. President Nixon took office in January 1969 and replaced him.

Komer then worked as a consultant with the Rand Corp., writing classified studies on NATO and on the need for a rapid-deployment force for the Persian Gulf, until the next Democratic administration.

He became undersecretary of defense for policy under President Carter and put many of those ideas into effect. His staff presented him with a bronzed blowtorch, a symbol of his past battles.

Komer was born in Chicago. He graduated from Harvard in 1942, served in the Army in World War II and, after having graduated from the Harvard Graduate School of Business in 1947, joined the new CIA. He became a senior intelligence analyst, peering into nations from Morocco to Malaysia.

After leaving the Pentagon and in the clear light of hindsight, he waxed bittersweet about Vietnam. “I would have done a lot of things differently and been more cautious about getting us involved,” he said. He called the war “a strategic disaster which cost us 57,000 lives and a half trillion dollars.”

Komer’s first marriage, to Jane Komer, ended in divorce. His second wife, Geraldine, died in 1996. Survivors include three children from the first marriage, Doug, of Annandale, Va.; Dick, of Falls Church, Va.; and Anne, of Boston; a sister; five grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

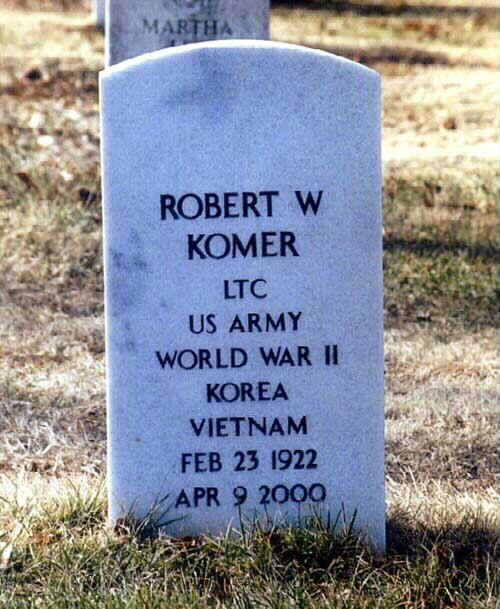

KOMER, ROBERT WILLIAM, LT. COL. USA (Ret.)

On Sunday, April 9, 2000 at Arlington Hospital, ROBERT W. KOMER of Arlington, Virginia, husband of the late Geraldine P. Komer; father of Douglas R., Richard D. and Anne E. Komer; brother of Peggy Bearman. Also survived by five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Private interment Arlington National Cemetery. In lieu of flowers, memorials may be made to The American Cancer Society Memorial Fund, P.O. Box 7089, Arlington VA 22207, or the National Center for Family Literacy, 325 West Main St., Louisville, Kentucky 40202

Komer, Geraldine P,

- Born 10 December 1924

- Died: 13 February 1996

- United States Navy SF/1

- Residence: Alexandria, Virginia

- Section 11, Grave 674-1

- Buried: 22 February 1996

Komer, Robert W,

- b. 02/23/1922, d. 04/09/2000

- U.S. Army, Lieutenant Colonel

- Res: Falls Church, Virginia

- Section 11, Grave 674-1, buried 28 April 2000

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard