Refugio Thomas Teran was born on May 8, 1949 and joined the Armed Forces while in Westland, Michigan.

He served in the United States Army, Company E 2nd Battalion, 501st Airborne, and attained the rank of Staff Sergeant.

Refugio Thomas Teran is listed as Missing in Action.

From a press report: 26 March 2002:

MIA’s body returned home after 32 years

Westland soldier to be buried at Arlington

Westland, Michigan — Thirty-two years after he vanished in the jungles of Vietnam, Refugio Thomas Teran is coming home. Home to the parents who never stopped waiting and hoping, home to the friends who never forgot the handsome boy with the generous heart. Home to a hero’s burial, with full military honors, in Arlington National Cemetery.

“I was praying for this, and I just thank my God for giving me this gift,” said his mother, Anna Bertha Teran, 76, as she sat in her Westland home, surrounded by pictures of her lost son. “I only wish I could share what I’m feeling with all the other families who are still waiting.”

The recovery and identification of Tom Teran — last seen in the middle of a fierce firefight in the predawn hours of May 6, 1970 as Viet Cong forces overran the munitions dump he was guarding on Henderson Hill, Quang Tri Province — brings the number of U.S. servicemen still missing in Southeast Asia to 1,932.

Teran is the first Michigan MIA to come home since construction began on the new Vietnam memorial in Lansing. His return leaves 60 names among the missing.

“Every one of those names is a story. Every one of them is just so important to us,” said Marty Eddy, president of the Prisoners of War Committee of Michigan.

The U.S. government spends $55 million a year in an effort to retrieve the lost casualties of the Second World War, Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War and assorted Cold War skirmishes — 88,000 missing servicemen in all. Since the United States and Vietnam restored diplomatic ties in 1992, the Defense Department has deployed 69 search teams to Southeast Asia, excavating crash sites and battlefields, interviewing aging civilians and soldiers, tracking rumors of unreturned prisoners of war.

“Our boy is found. But we’re going to keep looking for the boys who are left,” said his father, Refugio Teran, 83. For three decades, the Terans have lobbied the Vietnamese and U.S. governments to search for their son. They collected petitions, traveled the state speaking to groups, searched military records and tracked down anyone who might have been near their son that day. And as the years passed, they watched other parents grow old and die, their questions unanswered.

“We’re the only parents who show up for the (POW/MIA family) meetings now,” his father said. “Every year there were less and less of us.”

The Terans have their answers now, and the short story of their son’s life finally has an ending, even if it’s not a happy one. No longer missing, but still sorely missed, Tom Teran was born on Mother’s Day 1949 and lost on Mother’s Day 1970, two days shy of his 21st birthday.

After a brutal firefight, the Americans held the hill. The next day, a search and recovery detail retrieved five injured servicemen and 33 bodies, but found no trace of Private First Class Tom Teran and another rifleman, Larry Kier of Tennessee.

In those days, families of the missing were expected to suffer in silence. Not Anna and Refugio Teran, who, when their children were growing up, always insisted that the sleep-overs be at their house, so they could keep an eye on everyone. Who tailed the bus carrying their newly inducted son past the city limits, hoping for one last glimpse of him. Who sent him enormous care packages every week and insisted he write and call whenever he could — so they would know where he was.

The military sent condolences, and a box of medals Teran had never told his parents he’d earned. They promoted him twice during the eight years he was officially listed as Missing in Action.

“I don’t want any medals, I told them. You stay behind and you find my son,” Anna Teran told the officers. They sent the medals anyway, which sit in their velvet case in the living room. “That’s all I have left now of my Tommy. My jewels are my children, and right now I have lost one of the biggest jewels I had.”

And so, when the Department of Defense closed the books on the Teran investigation in 1978, the Terans took over.

“For your kid, you do anything,” said Refugio Teran. By the time the United States renewed its commitment to retrieving all the war missing in 1992, the Terans knew almost everything about their son’s last days. They tracked down his buddies, they tracked down the Vietnamese family Tom used to feed from his weekly care packages, they tracked down survivors of the battle. One of his uncles, a career military man, spent a year in Vietnam searching the region where he was lost.

That May 5, Tom Teran and his buddies were relaxing at the Eagle Beach Rest and Recovery Area, rejoicing over a larger-than-usual birthday care package from home, crammed with cake and all the fixings for a party. Teran, always happy to share the wealth, strolled over to another serviceman standing nearby and looking lonely, and invited him to join the party.

“Hi! I’m Tom Teran from Westland, Michigan, and it’s my birthday,” he introduced himself, and together the group set off to get ready for the party and do a little Mother’s Day shopping. He mailed off a package of presents for home and scrawled a quick note, describing his day, reassuring his mother he’d taken communion that morning, and mentioning the name of his new friend — a kid named Silva from Holland, Michigan.

Later, his parents tracked down that soldier, in the V.A. hospital where he lay with his arm gone and half his face blown away in the battle for Henderson Hill. It was he, not the Army, who told them about the alarm that sounded and the helicopters that scooped up all the soldiers on the base to defend the bunker. He gave them the horrific details of the battle, where he had fought, back-to-back with Teran until they lost track of each other in the fighting. The last thing anyone saw of Teran was a glimpse of him running toward a barricade.

Now they also have a thick folder from the military’s decade-long search for their son. They know now that a villager, scavaging scrap in the area, found their son’s body later in 1970 and buried it under a simple marker. Searchers from the military’s Joint Task Force-Full Accounting excavated Henderson Hill in 1992, but maddeningly, missed the grave and marker by just 200 yards. His remains were finally located in 1996, but the final identification wasn’t complete until last December.

“I kept saying, ‘All I want for Christmas is to know something about my son,’ ” said Anna Teran.

Tom Teran’s return will be marked with a series of memorials around Metro Detroit: in his hometown of Westland; at the VFW post that adopted his cause and supported his family all those years; and at the POW/MIA memorial in Novi, which will add one more return date to the bronze plaque on National POW/MIA Recognition Day in September. Dozens of supporters also plan to join the family at the memorial ceremony in Arlington on April 19.

“To me, it’s surprising, after all these years, that so many people still remember,” said Refugio Teran. “It does something for you. It gives you a little bit of comfort that all these people are there for you.”

Refugio Thomas Teran will be buried with full military honors Friday, April 19, in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. There will be several memorial services in Michigan as well, including:

* A memorial mass at 11:30 a.m. Saturday, April 13, at St. Theodore Church, 8200 N. Wayne, Westland.

* A memorial service at 3 p.m. Sunday, May 5, at Bova VFW Post #9885, 6440 N. Hicks, Westland.

* A special ceremony during POW/MIA Recognition Day at the POW/MIA Memorial at the Oakland Memorial Gardens cemetery, at 12 Mile and Novi Road in Novi.

* Memorial contributions may be made in Teran’s name to the POW Committee of Michigan, 2416 Harmony Dr., Burton, Michigan 48509.

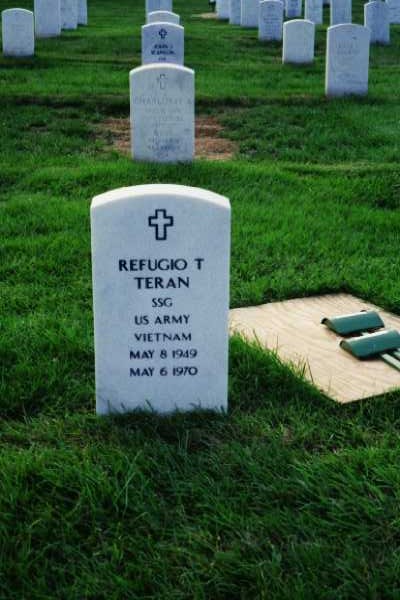

TERAN, REFUGIO THOMAS

Remains Identified 03/2002

Name: Refugio Thomas “Tom” Teran

Rank/Branch: E3/US Army

Unit: 2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry, 101st Airborne Division

Date of Birth: 08 May 1949 (Detroit Michigan)

Home City of Record: Westland Michigan

Date of Loss: 06 May 1970

Country of Loss: South Vietnam

Loss Coordinates: 163840N 1065600E (YD081411)

Status (in 1973): Missing In Action

Category: 2

Acft/Vehicle/Ground: Ground

Refno: 1613

Source: Compiled from one or more of the following: raw data from U.S. Government agency sources, correspondence with POW/MIA families, published sources, interviews. Updated by the P.O.W. NETWORK in 2002.

Other Personnel In Incident: Larry G. Kier (missing)

REMARKS:

SYNOPSIS: Every week while he was in Vietnam, Refugio Teran got a package from his mother containing 30 pounds of oatmeal, canned fruit and sugar, which Teran gave to a Vietnamese family near the base where he was

stationed.

On May 4, “in the world”, National Guardsmen had been called in to control rioting at Kent State and then Governor Ronald Reagan ordered California universities closed for the rest of the week.

During the night of May 5, 1970 (12 hours in time behind Vietnam time), Mrs. Anna Teran woke up screaming, knowing she would lose her son.

On May 6, 1970, PFC Larry G. Kier and PFC Refugio T. Teran were assigned to separate companies of the 101st Airborne Division as riflemen defending an artillery fire support base in South Vietnam.

At about 0500 hours on May 6, 1970, Viet Cong forces overran a guard station at an ammunition dump near Henderson Hill in Quang Tri Province, South Vietnam, killing 33 Americans. Kier and Teran were last seen running toward a barricade, and when not seen again, were presumed dead. Kier’s position was reportedly hit by a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG), and then napalm ignited in his location which was leaking from a nearby position. PFC Teran had been located in another firing position along the camp perimeter.

The next day, a graves registration detail collecting bodies was unable to find any trace of Kier and Teran. Five others in the unit who had been believed dead were found alive, but injured.

When 591 Americans were released from Vietnam in 1973, Kier and Teran were not among them. There has been no word surface about them since they disappeared.

SMITH 324 COMPELLING CASES

South Vietnam

Larry G. Kier

Refugio T. Terran

On May 6, 1970, Private First Class Kier and Private First Class Terran were at a fire support base in Quang Tri Province. Their position came under an enemy attack and a nearby ammunition dump 20 meters from their bunker was hit by a rocket propelled grenade. Napalm from the ammunition dump leaked into their position which

caught fire and burned. After the attack Terran could not be located, and Kier, at a separate location, could not be located either. Both individuals were declared killed in action, body not recovered in the late 1970s.

In August 1991, a Vietnam resident turned over the partially melted identity card belonging to Kier together with two bone fragments. The bones were reportedly recovered during 1987 and were turned over to a U.S. representative in Hanoi. The fragments are currently undergoing analysis.

LEAGUE UPDATE: March 7, 2002

AMERICANS ACCOUNTED FOR: According to the Department of Defense, there are now 1,936 Americans still missing and unaccounted for from the Vietnam War. Most recently, remains jointly recovered in June, 1994, were identified as Air Force Colonels Peter M. Cleary of CT and Leonardo C. Leonor of NY, both listed as MIA October 10, 1972 in North Vietnam. Also recently identified were Army SSGs Larry G. Kier of NB and Rufugio T. Teran of MI, missing in a South Vietnam ground incident since May 6, 1970. Local villagers initially provided remains in August 1992; joint operations resulted in further information and remains. Others recently accounted for include Air Force Col William C. Coltman of PA and LtCol Robert A. Brett, Jr., of OR, missing in Laos since September 29, 1972, with remains jointly recovered August 28, 2000.

MIA’s body returned home after 32 years Westland soldier to be buried at Arlington

March 26, 2002

WESTLAND — Thirty-two years after he vanished in the jungles of Vietnam, Refugio Thomas Teran is coming home.

Home to the parents who never stopped waiting and hoping, home to the friends who never forgot the handsome boy with the generous heart. Home to a hero’s burial, with full military honors, in Arlington National Cemetery.

“I was praying for this, and I just thank my God for giving me this gift,” said his mother, Anna Bertha Teran, 76, as she sat in her Westland home, surrounded by pictures of her lost son. “I only wish I could share what I’m

feeling with all the other families who are still waiting.”

The recovery and identification of Tom Teran — last seen in the middle of a fierce firefight in the predawn hours of May 6, 1970 as Viet Cong forces overran the munitions dump he was guarding on Henderson Hill, Quang Tri

Province — brings the number of U.S. servicemen still missing in Southeast Asia to 1,932.

Teran is the first Michigan MIA to come home since construction began on the new Vietnam memorial in Lansing. His return leaves 60 names among the missing.

“Every one of those names is a story. Every one of them is just so important to us,” said Marty Eddy, president of the Prisoners of War Committee of Michigan.

The U.S. government spends $55 million a year in an effort to retrieve the lost casualties of the Second World War, Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War and assorted Cold War skirmishes — 88,000 missing servicemen in all. Since the

United States and Vietnam restored diplomatic ties in 1992, the Defense Department has deployed 69 search teams to Southeast Asia, excavating crash sites and battlefields, interviewing aging civilians and soldiers, tracking

rumors of unreturned prisoners of war.

“Our boy is found. But we’re going to keep looking for the boys who are left,” said his father, Refugio Teran, 83. For three decades, the Terans have lobbied the Vietnamese and U.S. governments to search for their son.

They collected petitions, traveled the state speaking to groups, searched military records and tracked down anyone who might have been near their son that day. And as the years passed, they watched other parents grow old and

die, their questions unanswered.

“We’re the only parents who show up for the (POW/MIA family) meetings now,” his father said. “Every year there were less and less of us.”

The Terans have their answers now, and the short story of their son’s life finally has an ending, even if it’s not a happy one. No longer missing, but still sorely missed, Tom Teran was born on Mother’s Day 1949 and lost on

Mother’s Day 1970, two days shy of his 21st birthday.

After a brutal firefight, the Americans held the hill. The next day, a search and recovery detail retrieved five injured servicemen and 33 bodies, but found no trace of Pfc. Tom Teran and another rifleman, Larry Kier of

Tennessee.

In those days, families of the missing were expected to suffer in silence. Not Anna and Refugio Teran, who, when their children were growing up, always insisted that the sleep-overs be at their house, so they could keep an eye on everyone. Who tailed the bus carrying their newly inducted son past the city limits, hoping for one last glimpse of him. Who sent him enormous care packages every week and insisted he write and call whenever he could — so they would know where he was.

The military sent condolences, and a box of medals Teran had never told his parents he’d earned. They promoted him twice during the eight years he was officially listed as Missing in Action.

“I don’t want any medals, I told them. You stay behind and you find my son,” Anna Teran told the officers. They sent the medals anyway, which sit in their velvet case in the living room. “That’s all I have left now of my Tommy. My jewels are my children, and right now I have lost one of the biggest jewels I had.”

And so, when the Department of Defense closed the books on the Teran investigation in 1978, the Terans took over.

“For your kid, you do anything,” said Refugio Teran. By the time the United States renewed its commitment to retrieving all the war missing in 1992, the Terans knew almost everything about their son’s last days. They tracked down his buddies, they tracked down the Vietnamese family Tom used to feed from his weekly care packages, they tracked down survivors of the battle. One of his uncles, a career military man, spent a year in Vietnam searching the region where he was lost.

That May 5, Tom Teran and his buddies were relaxing at the Eagle Beach Rest and Recovery Area, rejoicing over a larger-than-usual birthday care package from home, crammed with cake and all the fixings for a party. Teran, always happy to share the wealth, strolled over to another serviceman standing nearby and looking lonely, and invited him to join the party.

“Hi! I’m Tom Teran from Westland, Michigan, and it’s my birthday,” he introduced himself, and together the group set off to get ready for the party and do a little Mother’s Day shopping. He mailed off a package of presents for home and scrawled a quick note, describing his day, reassuring his mother he’d taken communion that morning, and mentioning the name of his new friend — a kid named Silva from Holland, Mich.

Later, his parents tracked down that soldier, in the V.A. hospital where he lay with his arm gone and half his face blown away in the battle for Henderson Hill. It was he, not the Army, who told them about the alarm that sounded and the helicopters that scooped up all the soldiers on the base to defend the bunker. He gave them the horrific details of the battle, where he had fought, back-to-back with Teran until they lost track of each other in the fighting. The last thing anyone saw of Teran was a glimpse of him running toward a barricade.

Now they also have a thick folder from the military’s decade-long search for their son. They know now that a villager, scavaging scrap in the area, found their son’s body later in 1970 and buried it under a simple marker. Searchers from the military’s Joint Task Force-Full Accounting excavated Henderson Hill in 1992, but maddeningly, missed the grave and marker by just 200 yards. His remains were finally located in 1996, but the final identification wasn’t complete until last December.

“I kept saying, ‘All I want for Christmas is to know something about my son,’ ” said Anna Teran.

Tom Teran’s return will be marked with a series of memorials around Metro Detroit: in his hometown of Westland; at the VFW post that adopted his cause and supported his family all those years; and at the POW/MIA memorial in Novi, which will add one more return date to the bronze plaque on National POW/MIA Recognition Day in September. Dozens of supporters also plan to join the family at the memorial ceremony in Arlington on April 19.

“To me, it’s surprising, after all these years, that so many people still remember,” said Refugio Teran. “It does something for you. It gives you a little bit of comfort that all these people are there for you.”

These medals reflect the military history of Teran, who was killed in 1970 while guarding an ammunition dump in Quang Tri Province.

Upcoming services

Refugio Thomas Teran will be buried with full military honors Friday, April 19, in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. There will be several memorial services in Michigan as well, including:

A memorial mass at 11:30 a.m. Saturday, April 13, at St. Theodore Church, 8200 N. Wayne, Westland.

A memorial service at 3 p.m. Sunday, May 5, at Bova VFW Post #9885, 6440 N. Hicks, Westland.

A special ceremony during POW/MIA Recognition Day at the POW/MIA Memorial at the Oakland Memorial Gardens cemetery, at 12 Mile and Novi Road in Novi.

Memorial contributions may be made in Teran’s name to the POW Committee of Michigan, 2416 Harmony Dr., Burton, Mich. 48509.

Refugio Teran, left, sits on a couch as his wife, Anna Bertha Teran,

looks at a photo of their son, Staff Sergeant Refugio Thomas Teran,

whose remains were recently discovered in Vietnam and returned

to the United States.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard