Son of John Augustus and Elizabeth Rodgers. He was the co-designer of the Wright Brothers Memorial at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. (1895-1934).

He is buried with his parents in Section 1, Arlington National Cemetery.

1930: The architects for the new building that is to be built for the Cape Playhouses, Inc., in Dennis are Robert Perry Rodgers and Alfred Easton Poor, of New York City and are now preparing the plans.

Courtesy of the National Park Service

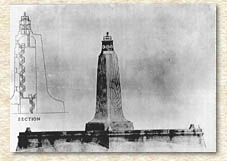

The first organized preservation effort at the Wright Brothers site was launched in 1927 by the newly formed Kill Devil Hills Memorial Association. During its early planning stages, the Association imagined a future museum at the site, but a more immediate concern was the construction of an appropriate memorial atop its namesake sand dune. Congress authorized the Kill Devil Hill Monument National Memorial in March 1927, and the cornerstone for the structure was laid during the next year’s anniversary celebration. Rodgers and Poor, a New York architectural firm, designed the 60-foot-high Art Deco granite shaft in 1931-1932. Crowned with a navigational beacon accompanied by its own power house, the tremendous pylon was ornamented by bas-relief wing designs.

Kill Devil Hill was not the site of the Wright Brothers’ achievement, but the launching point for earlier glider experiments and a location closer to the heavens than the Wrights’ primitive airstrip on the flat land north of the dune. When the Wrights set up camp here from 1901-1903, this land was constantly shifting sands. The Quartermaster Corps used sod and other plantings to stabilize the sand hill when the area was still under the jurisdiction of the War Department. In addition, the Kill Devil Hills Association marked the location of the first flight with a commemorative plaque.

During the 1930s, plans for the Memorial included a park laid out in the Beaux-Arts tradition, with a formal mall leading to a central garden flanked by symmetrical hangers and parking lots. An airport served as the flat land terminus of the axis, and the Kill Devil Hill memorial as its culmination; six roads radiated out from the monument to the borders of the park. Although this scheme was never implemented, the system of trails and roads constructed by the Park Service in 1933-1936 formed the basis for today’s circulation pattern. A brick custodian’s residence (1935) and maintenance area (1939) were built south of the hill.

When the monument was planned in the late 1920s, Congressman Lindsay Warren imagined a museum “gathering here the intimate associations,” and “implements of conquest.” Almost twenty years later, an “appropriate ultra-modern aviation museum” was proposed for Wright Brothers during the effort to obtain the original 1903 plane, but funding was not forthcoming. Such an ambitious construction project began to seem possible in 1951, when the memorial association reorganized as the Kill Devil Hills Memorial Society, and prominent member David Stick established a “Wright Memorial Committee.” Stick realized that a museum could only succeed with assistance from the National Park Service, local boosters, and corporate sponsors. Among the committee members recruited for the development campaign were Paul Garber, curator of the National Air Museum in Washington; Ronald Lee, assistant director of the Park Service; and J. Hampton Manning, of the Southeastern Airport Mangers Association in Augusta. In preparation for the first meeting, the Park Service drafted preliminary plans for a museum facility dated February 4, 1952.

Regional Director Elbert Cox introduced the project as a “group of buildings of modern form” to be located off the main highway northeast of the monument. The proposed Wright Brothers Memorial Museum included a “court of honor,” “Wright brothers exhibit area,” “library and reception center,” and funnel-shaped “first flight memorial hall” with outdoor terraces facing the view of the first flight marker to the north and Wright memorial marker to the west. The exhibit galleries were to contain “scale models of the various Wright gliders and airplanes, a topographic map of the area at the time of their experiments, scale models of their bicycle shop and wind tunnel, and photographic and other visual exhibits.” One wing of the complex housed offices for the museum curator and superintendent, workshop and storage rooms, and a service court. In elevation, the northwest facade is multiple flat-roofed buildings adjacent the double-height memorial hall, a slightly peak-roofed room with glass and metal walls.

Although it could not provide adequate funding for the museum, the Park Service entered into the planning process in earnest, producing revised plans and specifications in August 1952. Director Wirth looked “forward with enthusiasm to the full realization of the . . . program,” and promised that the Park Service would operate and maintain the facility once constructed. He even included cost estimates for the buildings, structures, grounds, exhibits, furnishings, roads, and walks. During the summer, word of a potential commission spread and several regional architects notified Stick of their design services. Despite much effort, however, the committee was unable to raise funds for the million dollar complex, which was originally slated for completion by the fiftieth anniversary.

Several smaller goals were achieved in time for the December 1953 celebration: the monument was renamed the Wright Brothers National Memorial, entrance and historical markers established, and reconstructions of the Wrights’ living quarters, hanger, and wooden tracks constructed. Though disappointed at the lack of financial backing for the museum, the committee “strongly felt that the original plans for the construction of a Memorial Museum at the scene of the first flight should remain an objective of the Memorial Society.” The establishment of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, also in 1953, may have contributed to their continued optimism.

Four years after the committee’s initial attempt to fund an aviation museum, the National Park Service surprised all concerned with an offer to sponsor a scaled-down version of the facility. The committee met in Washington on October 23, 1957, only to learn that funds from the aircraft industry would not be forthcoming. During this meeting, Conrad Wirth outlined his Mission 66 program and revealed that a visitor center at Wright Brothers was included among the proposed construction projects.

After further consideration, Wirth promised to make the Wright Brothers facility an immediate objective “by shifting places on the list with one of several battlefield visitor centers planned in advance of the forthcoming Civil War centennial.”

Just four years earlier, the Park Service had planned a modernist museum for the site on the scale of a Smithsonian, with the free-flowing design of a public building typical of the period. The visitor center of 1957 did not have the aesthetic freedom of a such a museum. For its Mission 66 visitor center, the Park Service sought a smaller, less expensive, more compact structure with distinct components: restrooms (preferably entered from the outside), a lobby, exhibit space, offices, and a room for airplane displays and ranger programs (in place of the standard audio-visual room or auditorium). As designers of the new building, the Park Service chose a new architectural firm based in Philadelphia: Mitchell, Cunningham, Giurgola, Associates, which was soon known as Mitchell/Giurgola, Architects. With its symbolism of innovation, experimentation and evolving genius, the building was an ideal commission for the fledgling firm.

Robert Perry Rodgers (1895-1934) and Alfred Easton Poor (1899-1988) both received their undergraduate architectural education at Harvard University. Rodgers went on to earn a degree from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1920 and work in Bertram Goodhue’s New York office. Poor continued his education at the University of Pennsylvania, joining Rodgers in the late 1920s for collaboration on an office building.

COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

THE WRIGHT BROTHERS NATIONAL MEMORIAL

THE MEMORIAL TOWER

The Wright Brothers Memorial Act called for the Secretaries of War, Navy, and Commerce to appoint a memorial committee to establish an appropriate site for a commemorative monument and to appoint a second committee to oversee the construction of the monument and plan for its dedication. The standing Commission of Fine Arts and the Joint Committee on the Library received responsibility for approval of the final design and for other plans for the memorial. Other individuals involved, both formally and informally, in decisions concerning the monument included future President Herbert Hoover, Charles Lindbergh, Cecil B. DeMille, Joseph Pulitzer, Fiorella LaGuardia, Commander Richard E. Byrd, General John J. Pershing, and Harry Guggenheim, all of whom joined the Kill Devil Hills Memorial Association, a national and local support group for the project founded August 27, 1927.

Beginning in the summer of 1928, a joint effort of the Coast Guard and local citizens partially stabilized the large hill at Kill Devil Hills through an encircling band of shrubs and stub grass in order to help prepare the hill for a planned larger monument. This became the first major alteration of the site; the War Department eventually stabilized, planted with shrubs and trees, and sodded the ground, preventing the continued southwest migration of Big Kill Devil Hill and altering forever the once barren scene of the first flight.

The beginning of the construction of the principal monument as set out in the 1927 Congressional Act began with the laying of the cornerstone at the top of Big Kill Devil Hill on December 17, 1928, just prior to the ceremonial unveiling of a small rock-faced granite marker placed at the 1903 first flight lift-off site. W.O. Saunders, Senator Hiram Bingham of Connecticut, and Secretary of War Dwight Davis addressed the gathering which was attended by Orville Wright and Amelia Earhart. After the laying of the cornerstone, the Norfolk Naval Station band played “The Star-Spangled Banner.” However, the selection of the actual design for the monument had not yet been accomplished.

SELECTION OF THE MONUMENT DESIGN

All the interested parties immediately disagreed over the monument design and function. The Memorial Commission, established by the act, dealt with all concerns. Congressman Lindsay Warren expressed hopes “that the plans will call for something grand and artistic which will worthily mark the public recognition of what the achievement signified.” Another suggestion called for the monument to be combined with a new structure for the lifesaving station at Kitty Hawk, then in disrepair. William P. MacCracken, Jr., the Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aeronautics, as well as Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, supported this proposal. As Hoover expressed it, he was reluctant to dump “a quarter of a million dollars of public money on a sand dune where only a few neighborhood natives would see it.” Hoover also suggested a marine light to further the monument’s utility.

The Commission of Fine Arts, retaining the right of final design approval, rejected the utilitarian proposals put forward by the Memorial Commission and Hoover, favoring a purely commemorative structure. Senator Bingham especially expressed his disagreement with the plan that attempted “to combine memory with utility.” He

promoted a Greek temple design, constructed from granite quarried in his home state. Nonetheless, utility ultimately won out. Charles Moore, Chairman of the Commission of Fine Arts, indicated to the Memorial Commission that the final design included “a memorial tower which should carry a powerful light to air flyers… [and] a landing place for planes.” While the commemorative airstrip took many years to be realized, the final design included a beacon, though as one of the architects recorded, it was more a memorial with a beacon than a beacon glorified as a memorial.

Much of this controversy over the design took place in the early part of 1928, before the official unveiling ceremony for the smaller marker and dedication of the cornerstone. By June 1928, the Office of the Quartermaster General, charged with supervising actual construction, realized the impossibility of a quick decision and announced a design competition. The Memorial Commission appointed members of a jury to select the winning design in accordance with principles established by the American Institute of Architects. While the jury awaited submitted designs, the Quartermaster General prepared a report on the site, which suggested that the top of the largest hill at Kill Devil Hills would indeed be a suitable location for the monument. At first thought to be subject to further shifts and erosion, the hill consisted of moist and heavily compacted sand, which could be stabilized as a suitable base. Although selection of the final design was delayed until the early part of the following year, by October 1928 the site was finally agreed upon.

By January 31, 1929, the jury had received a total of thirty-six entries. The jury selected the submission of the New York architectural firm of Rodgers and Poor; and on February 18, 1929, the Commission of Fine Arts concurred, over the objections of Senator Bingham. The Joint Committee on the Library, of which Bingham was a member, held up the decision for nearly another year. On February 14, 1930, the firm of Rodgers and Poor finally received formal notification that their design won the $10,000 prize and that they were to proceed as architects for the construction of the monument.

Respected Beaux-Arts-trained architects, Rodgers and Poor were well suited to the task. Robert Perry Rodgers (1895-1934) graduated from Harvard University in 1917, and served in the Navy during World War I in an Atlantic transport unit. He studied at the famous Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, receiving a diploma in 1920. His early training began as a draftsman in Bertram Goodhue’s office in New York. Rodgers began his collaboration with Alfred Easton Poor (1899-1988) in the late 1920s, working on an office building for Little and Brown Publishers and a private studio on East 78th Street. Poor also attended Harvard, as well as the University of Pennsylvania, receiving degrees in architecture from both. His interests included historic American architecture, and in 1932 he published Colonial Architecture of Cape Cod Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket, still considered a standard work on the topic.

Interestingly, the Rodgers and Poor design was anything but traditional and, in fact, revealed strong ties to the then popular Art Deco movement — a movement traced to the 1925 Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels in Paris. Few designs of this style existed among federally sponsored buildings; most tended to be more fully in the classical and Beaux Arts tradition. Rodgers and Poor’s design gave expression to the “aesthetics of the machine.” Essentially a masonry shaft, about 60 feet high, the monument was embellished with highly stylized sculpted wings on each side to symbolize the ideas of flight and motion. The design implied ancient Egyptian motifs, an important source for Art Deco designs, which also drew upon Native-American and Asian precedents.

The Wright Brothers Monument was a design unequaled by other federal projects of the era, most of which focused on utilitarian functions and character. Among the other more noteworthy projects of the same period were the Arlington Memorial Bridge, the Deadwood Dam, and the Hoover Dam. In part to placate Senator Bingham, the commission authorized the architect to give even further embellishment to the building, emphasizing the design features of the memorial more than the functional qualities of the beacon. Simultaneously, the Quartermaster Corps agreed to construct the monument from North Carolina granite, rather than the concrete proposed by Rodgers and Poor, in deference to Congressman Warren. Most of the parties involved felt the resulting unique memorial, suffused with the appropriate symbolism and majesty, properly marked the site.

BUILDING THE MONUMENT

Before construction of the monument began, the site required further stabilization and construction of access roads. The Quartermaster General sought an appropriation for the necessary funds to carry out the work with support given by the Secretary and Assistant Secretary of War. In addition to the original $25,000 in preparation and planning money authorized by the 1927 act, the budget now reached a tremendous $277,688, well over the $100,000 originally considered. The War Department allotted some $25,000 of this amount to stabilization work, with leadership assigned to Captain William H. Kindervater of the Quartermaster Corps, appointed inspector of construction on January 16, 1929. Kindervater began work immediately. Most of the work involved the planting of grasses and shrubs, an effort presaged by Captain Gould, the caretaker of the nearby Bodie Island Gun Club, who first experimented with the use of dune grasses in the early-to-mid 1920s.

Kindervater found that the most serviceable grasses and shrubs were the locally available wire (bermuda) grass; Bitter Tanic, gathered at nearby Virginia Beach; and a range of local shrubs, including yaupon, myrtle, pine, live oak, and sumac, among others. As early as January 1929 he worked out a formula for fertilizer to encourage the growth of vegetation on the shifting sand hills. In April he wrote the Senior Agronomist at the Department of Agriculture for suggestions on “any seed that has a pretty flower … [in order to] spell out the words Kill Devil Hill in flowers,” an idea never acted upon. He also sought to protect the site from “the molestation of tourists and souvenir collectors, and the avages of wild hogs,” and to this end he constructed a wire fence around a portion of the site to prevent animal grazing on the newly planted grass. In August, apparently in recognition of his success, Kindervater received a promotion from inspector to superintendent of construction.

Kindervater chose a relatively straightforward method for stabilizing the hill and surrounding area. He harrowed the site, loosening sand and soil; spread a two-inch layer of pine straw, rotted leaves, and wood mold; sowed grass seed; and then covered the whole with brush to protect new growth. The area also received heavy fertilization. The dune withstood storms in 1929 and 1930, justifying the operation. The successful work at the Kill Devil Hills site helped lay the groundwork for the massive dune stabilization project along the proposed national seashore at Cape Hatteras during the mid- to late-1930s.

Congress confirmed appropriations for the building of the Rodgers and Poor-designed monument in December 1930. The contract documents were released shortly afterward (Specifications for Construction of Wright Brothers Memorial 1930). The Office of the Quartermaster General appointed Marine Captain John A. Gilman as the Constructing Quartermaster of the site. The Wills and Mafera Corporation of New York won the bid for general contractor around the same time, quoting a low bid of $213,000 for the monument and a powerhouse at the foot of the main Kill Devil Hill. Construction specifications, dated November 1, 1930, called for a granite tower, 61 feet high, with a base measuring 36 by 43 feet (Specifications for Construction of Wright Brothers Memorial 1930). Plans called for the use of stainless steel for the metal fittings, except for roofing, flashing, and thresholds, which were copper and bronze. The tower included a light beacon, but the contract described only the mounting, not the installation of the light. The War Department designed the more utilitarian powerhouse that supplied electricity to the monument’s beacon.

The contractors scheduled construction beginning February 1931 following the completion of Captain Kindervater’s work on stabilization and road construction. Materials arrived late, delaying the project start to October of that year.

Wills and Mafera received bids for granite from a number of companies in New England and North Carolina. The Sargent Granite Company of Mount Airy, North Carolina, received the contract award. The same company provided the material for the Arlington Memorial Bridge in Washington, D.C., and for the Gettysburg Memorial in Pennsylvania, two other important federal projects of this period, securing their reputation. The stone traveled to the site by railroad via Norfolk and Elizabeth City and then by barge and truck to the Kill Devil Hills reservation. The bridge at Kitty Hawk opened that spring, and allowed smaller pieces to be delivered directly by truck. Larger stones required on-site rails for moving.

Work on the star-shaped granite base began in December 1931. Granite blocks were lifted into place by a crane mounted on the hillside. In all, the project required nearly 1,200 tons of granite, more than 2,000 tons of gravel, more than 800 tons of sand, and nearly 400 tons cement. Each construction crew averaged more han fifty men. Many local residents participated in the onstruction, giving them their first experience with government-sponsored projects on the Outer Banks.

The crews completed the monument construction in November 1932. By this time the site included the new monument on top of the big hill and its associated powerhouse, the original granite first flight lift-off marker north of the new monument, a road from state route 158 leading to the park boundary, a park road circling the east side of monument hill and turning due north to circle the granite marker, and a straight pedestrian trail leading from the road at the base of Kill Devil Hill to the monument. The War Department placed the memorial under the jurisdiction of the Commanding General of the Fourth Corps Area and appointed a caretaker to maintain and protect the monument. The Quartermaster General recommended Joseph Partridge, a local resident who worked as a foreman on the project, for the job of caretaker. Orville Wright and “25 outstanding citizens” including President Hoover, favored Captain William (Bill) Tate, the former Kitty Hawk postmaster who played such a central role in attracting the Wrights to the site in the first place. Surprisingly, the Quartermaster General selected Partridge. When Partridge died early the following year, Kindervater served as a temporary replacement, receiving help from an unskilled laborer.

Plans for the dedication of the monument began the summer before the scheduled completion date of October 1, 1932. Despite a pending presidential election, General Louis H. Bash, the Acting Quartermaster General, chose November 19, the Saturday after elections, as the dedication date. Soldiers from Fort Monroe, Virginia, volunteered to participate in the ceremony. The U.S. Navy planned to send a dirigible, and the Army a bomber and fighter squadron for an aerial display. Members of Congress, local dignitaries, military officers connected with the project, well-known aviators, and aircraft manufacturers, as well as the President of the United States, received invitations to the event. Orville Wright headed the list as the guest of honor. Boats chartered from Washington provided a round-trip excursion fare of $7.50. Organizers provided bleachers for 2,000 people and parking for 1,000 cars. In all, they anticipated as many as 20,000 spectators.

Dedication day arrived with heavy rains and high winds. Neither the dirigible nor the airplanes received permission to leave their bases, and estimated attendance reached no more than 1,000. General Bash, acting as master of ceremonies, read a letter from President Hoover expressing his regret at not being able to attend. Refraining from any general address to the audience, Orville later confided that he felt the monument was “distinctive, without being freakish.” At the end of the ceremony, aviator Ruth Nichols pulled a cord to officially mark the dedication of the monument. The cord released a well-drenched American flag concealing the word GENIUS in the inscription along the base of the monument:

IN COMMEMORATION OF THE CONQUEST OF THE AIR

BY THE BROTHERS WILBUR AND ORVILLE WRIGHT

CONCEIVED BY GENIUS

ACHIEVED BY DAUNTLESS RESOLUTION AND UNCONQUERABLE FAITH

While a few details still remained to be finished, including the beacon grill, the ventilator covers, and the entrance gates (these were under separate contract), the monument was complete.

RODGERS, ROBERT PERRY

- ENSIGN USNRF

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 06/04/1934

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 06/06/1934

- BURIED AT: SECTION WEST SITE 130

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard