Courtsy of the United States Air Force

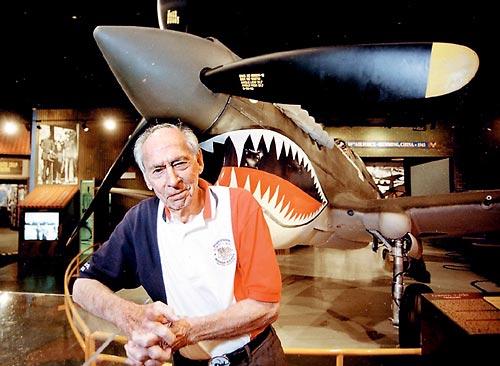

BRIGADIER GENERAL ROBERT L. SCOTT JR.

Retired September 30, 1957.

Robert Lee Scott was born in Macon, Georgia, in 1908. He graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1932, completed pilot training at Kelly Field, Texas, in October 1933 and was assigned to Mitchel Field, New York. Like other air officers, Scott flew the air mail in 1934, commanded a pursuit squadron in Panama and helped instruct other pilots at bases in Texas and California.

After World War II began, he went to Task Force Aquila in February 1942 to the China-Burma-India Theater where he pioneered in air activities. Within a month he was executive and operations officer of the Assam-Burma-China Ferry Command, forerunner of the famous Air Transport Command and Hump efforts from India to China.

At the request of Generalissmo Chiang Kai-Shek he was named commander of the Flying Tigers, formed by General Claire Chennault, and also became fighter commanding officer of the China Air Task Force, later to become the 14th Air Force.

He flew 388 combat missions in 925 hours from July 1942 to October 1943, shooting down 13 enemy aircraft to become one of the earliest aces of the war.

For his combat record against the enemy, Scott received two Silver Stars, three Distinguished Flying Crosses and three Air Medals, and was ordered back to the U.S. in October 1943 as deputy for operations in the School of Applied Tactics at Orlando, Florida.

He returned to China in 1944 to fly fighter aircraft equipped with experimental rockets directed against Japanese supply locomotives in eastern China. He then went to Okinawa to direct the same type of strikes against enemy shipping as the war ended.

Scott then returned to the U.S. for staff duty in Washington and other stations until the period of 1947-49 when he commanded the Jet Fighter School at Williams Air Force Base, Arizona. In late 1949 he went to Germany as commanding officer of the 36th Fighter Bomber Wing at Furstenfeldbruck.

He graduated from the National War College in 1954 and was assigned to Plans at Headquarters U.S. Air Force, and then to the position of director of information under the secretary of the Air Force. In October 1956 he went to Luke Air Force, Ariz., as base commanding officer.

General Scott has written several books including God Is My Copilot and Boring a Hole in the Sky.

28 February 2006

Courtesy of the Macon Telegraph

Retired Brigadier General Robert L. Scott, who packed more adventure in his life than any 10 people, according to his closest friends, died Monday at a Warner Robins nursing home. He was 97.

A native of Macon who grew up along Napier Avenue, Scott rose to nationwide prominence during World War II – first as a fighter ace in the China-Burma-India theater, then as author of “God Is My Co-Pilot,” an account of his wartime exploits. The book was later made into a 1945 feature-length movie.

Scott – who retired from the Air Force as a brigadier general – never lost his “fighter ace” prominence and later used that fame to great effect in supporting Middle Georgia’s Museum of Aviation.

“He’s been our resident hero, cheerleader and biggest fan,” said Pat Bartness, museum foundation president and chief operating officer. “He’s been the biggest drawing card we’ve had. Without him, the museum would just be a different place and not as exciting. He will be sorely missed.”

When Scott joined the museum staff in the mid-1980s, he had accomplished more than most people dream of, according to museum director Paul Hibbits.

“Because of that, his impact has not only been local but national,” Hibbits said. “I’ve run into people all over the country who have asked me about him. His being part of the museum has opened a lot of doors for us. He’s added a lot of credibility. He put us on the map.”

Born on April 12, 1908, Scott graduated from Macon’s Lanier High School. The summer between his junior and senior years, he took a job as deck boy aboard a Black Diamond Line freighter and sailed halfway around the world, the beginning of a lifetime of adventure.

But even before then, he exhibited his desire to fly. At age 12, he flew a home-built glider off the roof of a three-story house and crash-landed in a flower bed.

As Scott told the story: “Gliders were built out of spruce, but I didn’t have enough money, so I made mine out of knotty pine. I cleared the first magnolia, but then the main wing strut broke and I came down in Mrs. Napier’s rose bushes. It’s the only plane I ever crashed.”

Scott graduated from West Point as an Army second lieutenant in 1932 and completed pilot training a year later at Kelly Field, Texas. Before the war, he commanded a pursuit squadron in Panama, then instructed other pilots at bases in Texas and California.

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, he was considered too old for combat. But in March of 1942, he volunteered for a secret mission, “lied” about being qualified to fly the B-17 bomber and met Gen. Claire Chennault, the legendary commander of the Flying Tigers.

Chennault was leading a group of volunteer fighter pilots battling the Japanese over the skies of China and Burma. When the unit was inducted into the U.S. Army in July 1942, Scott was named commander of the newly formed 23rd Fighter Group. By October 1943, he had flown 388 combat missions, shot down 13 enemy aircraft and had become one of the first U.S. air aces of the war.

He was recalled to the United States and became a frequent speaker at war bond rallies across the nation. During a speech in New York, he met Charles Scribner, and the publisher encouraged Scott to write a book. Warner Brothers later purchased the movie rights and “God Is My Co-Pilot” became a national sensation. The book was a best seller and the movie held its world premiere in Macon.

The fighter ace later returned to the war, eventually downing a total of 22 enemy aircraft and hitting 10 supply trains before the conflict ended.

Following the war, Scott campaigned for separate service status for the Air Corps – a move that occurred in 1947 – and continued to lead fighter units in the United States and overseas. He commanded the nation’s first jet fighter school at Williams Air Force Base, Ariz., before his promotion to general officer and becoming the Director of Information for the Air Force.

He retired from the military in 1957 with 36 years in uniform. But in Scott’s case, retirement was nothing more than a transition. He continued speaking and writing, authoring at least 11 more books related to his Air Force experience.

At age 72, he walked the Great Wall of China, traveling almost 2,000 miles from Tibet to the Yellow Sea toting a knapsack filled with homemade oatmeal cookies.

In his 80s, he flew in modern F-16 and F-15 fighters and the B-1 bomber.

In 1996, at the age of 88, he ran with the Olympic Torch through Warner Robins.

Scott claims his association with the Museum of Aviation not only inspired his move to Warner Robins, but also saved his life. He told a Telegraph writer in 1996 that the museum gave his life new purpose.

“I was dying on the vine,” said Scott, who lived in Sun City, Ariz., before returning to Georgia. “I’ll always be grateful for the chance to come back.”

Scott’s close friend, retired Warner Robins physician Dan Callahan, remembers how Scott’s link with the local museum first developed.

“He came here to address an aircraft modelers association and met with Peggy Young,” Callahan remembered. Young was the museum’s director at the time. “She asked about (getting) some things for the museum and invited him back.”

After several trips from Arizona with the trunk of his Cadillac filled with memorabilia, Scott decided to move to Warner Robins.

“His coming was a godsend,” Callahan said. “We needed that personality to guide the museum through the early days. When he came on board, it was a foregone conclusion that it would be a success.”

Bartness said Scott made history come to life. “It’s one thing to read about history,” he said. “It’s another thing to sit with a guy who not only lived it but had a role so over the top, so huge.”

Bartness dismissed “the lie” Scott told about being qualified to fly the B-17. “He was so goal-oriented, he would have done anything to get into World War II,” Bartness said. “When you put it into perspective, what he wanted to do was defend his country. He never lost sight of his goal, which was to make a difference in the war.”

The museum executive said Scott’s contributions will be chronicled and long remembered. “Certainly we would not have had the ‘God Is My Co-Pilot’ or ‘The Flying Tigers’ exhibits,” he said, “nor our relationship with the Hump Pilots. He also was a big part of helping us build our archives.”

The museum’s former curator, the late Darwin Edwards, was asked several years ago to assess Scott’s impact on the museum. He agreed that Scott’s prestige-lending name was huge, along with his help in obtaining a variety of exhibits. But Edwards said Scott’s human touch was most vivid.

“He was always talking to kids – kids of all ages,” said Edwards. “He liked kids. He liked people in uniform. He just liked people period. He was a living legend. He added class, and the fact that he was a local boy just added that much more. We would be far less of a museum without him.”

Hibbits said Scott’s loss will be deeply felt.

“His vitality until just recently was extraordinary,” he said. “When he walked in the room, eyes would light up – for the kids, to be sure, but also for a lot of grown-ups. The experiences he’s had. The things he tells you. He’s lived two lifetimes. People just enjoyed being around him. We’ll miss him to be sure.”

Scott leaves a daughter, Robin Fraser, who lives in Bakersfield, California a grandson, three granddaughters and several great-grandchildren.

Brigadier General Robert L. Scott, Jr., 97, passed away on Monday, February 27, 2006 at Southern Heritage Personal Care Home. A memorial service will be held at 2 p.m., Friday, March 3, 2006 at Southside Baptist Church. Interment will be at Arlington National Cemetery. Visitation will be Thursday, March 2, 2006 from 5:30 – 8 p.m. at McCullough Funeral Home. In lieu of flowers, the family requests donations to be made to the Museum of Aviation, P. O. Box 2469, Warner Robins, Georiga 31099.

Known to his friends and family as “Scotty,” the retired general lived his final two decades as the champion and cheerleader of the Museum of Aviation in Warner Robins. He worked tirelessly to promote the educational value of the Museum and was responsible for raising millions of dollars for Museum development.

Born on April 12, 1908, Scott grew up in Macon, Georgia. He was a graduate Lanier High School and The United States Military Academy at West Point. He amassed over 42,000 flying hours in sixty years in a variety of aircraft ranging from the P-12 to the F-100 – a record which few pilots have ever reached. Official Army Air Force records credit him with thirteen aerial victories in his Curtiss P-40, but according to Scott it was really twenty-two, making him one of the top Air Force “Aces” of World War II.

His famous book “God Is My Co-Pilot” was a long standing best seller and still sells thousands of copies today. He served as technical advisor to Warner Brothers in making a movie based on the book. The World Premiere was at the Grand Theater in Macon, Georgia in 1945.

In 1986, Scott came to Warner Robins for the unveiling of an exhibit of his memorabilia at the Museum of Aviation. He was asked to stay and the next year moved to Warner Robins to become the head of the Heritage of Eagle Campaign which ultimately raised $2.5 million to build a 3-story Eagle Building at the Museum.

In 1988, Scott released his autobiography entitled “The Day I Owned the Sky.” That year, at age 82, he was cleared to fly in an Air National Guard F-15 Eagle out of Dobbins Air Force Base in Marietta Georgia. Two years later, he again flew the Eagle – this time at Robins Air Force Base in Warner Robins, Georgia. On April 2, 1997, in celebration of his 89th Birthday, Scott flew his last flight in a B-1 bomber assigned to the 116th Bomb Wing at Robins Air Force Base.

Survivors include his daughter, Robin Scott Fraser (Bruce), Bakersfield, California; grandchildren, Scott Simon Fraser, Rancho Santa Fe, California; Linda Mahan, Bakersfield, California; Laura Allen, Bakersfield, California; Susan Mulholland, Bakersfield, California; great grandchildren, John Mahan, Bryan Mahan, Heather Mahan, Michael Mulholland, Steven Mulholland, Bob Mulholland, Abigale Fraser, Lauren Fraser; great great grandchildren, Jesse Moore and Steven Mulholland. Scott’s wife of 38 years, Catharine Green Scott, of Fort Valley Georgia, died in 1972. His parents, Robert Lee Scott, Sr. and Ola Burckhalter Scott, also preceded him in death.

One of the armed forces’ prominent World War II heroes and driving forces behind the Museum of Aviation at Robins Air Force Base, Georgia, died February 27.

Retired Brigadier General Robert L. Scott Jr., a World War II ace fighter pilot, was 97 years old. General Scott also was known for his 1943 best-selling book, “God Is My Co-Pilot”, which Warner Brothers turned into a movie that premiered in 1945.

Memorial Services are being arranged at McCullough Funeral Home in Warner Robins. Burial will be at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

General Scott recorded 13 confirmed aerial victories during World War II while flying the P-40. He himself was never shot down. General Scott was a member of General Claire Chennault’s American Volunteer Group in China that was known as the “Flying Tigers.”

After the war, General Scott served in the Pentagon on a task force to win autonomy for the Air Force from the Army, which finally occurred in September 1947. In that year he was given command of the Air Force’s first jet fighter school at Williams Field, Arizona. He then moved to Europe in 1950 to command the 36th Fighter Wing at Furstenfieldbruck, Germany. In 1954, after graduating from the National War College he was promoted to brigadier general. He was assigned to Plans at Headquarters Air Force, and then to the position of Director of Information under the Secretary the Air Force.

General Scott retired in 1957.

In 1986, General Scott went to Warner Robins for the unveiling of an exhibit of his memorabilia at the Museum of Aviation. He was asked to stay and the next year moved to Warner Robins to become the head of the Heritage of Eagles Campaign, which ultimately raised $2.5 million to build a 3-story Eagle Building at the Museum.

His ties to the museum won’t be forgotten, according to the current Museum of Aviation director.

“To actually work with him, to actually see the passion he had about this museum and about the Air Force and history and to relay that passion to children and grown-ups, I think that will probably be something that I’ll always remember,” said Paul E. Hibbitts, who’s headed the facility since 2003.

“We have a wonderful museum,” said Mr. Hibbitts. “We wouldn’t have everything we have if it wasn’t for General Scott giving his time to us.”

(Editor’s note: Holly Birchfield, 78th Air Base Wing Public Affairs, along with the Museum of Aviation, contributed to this article.)

By Air Force Materiel Command Public Affairs

General Robert L. Scott; WWII Flying Ace

By Adam Bernstein

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Wednesday, March 1, 2006

Robert L. Scott, 97, an American flying ace who was once described as the “one-man air force” over China during World War II and whose exploits were turned into a best-selling book and then a film, died February 27, 2006, at an assisted living facility in Warner Robins, Georgia, after a stroke.

A mischievous, sometimes impolitic daredevil, he eventually rose to the Air Force rank of Brigadier General. The book, “God Is My Co-Pilot” (1943), and the 1945 film version made him a national name, and he later rounded out his career with several more acclaimed volumes about flying and elephant hunting.

However, General Scott was ultimately encouraged to retire in 1957 after his superiors frowned on his blunt remarks about the United States’ need to compete better against the Soviets during the space race.

“The only time I’ve ever been moderately successful is in combat,” he said during his prolific lecturing career in retirement. He added that he “was in the bottom of my class at West Point” because of “a goat mind. And a goat is the bottom of the bottom.”

The son of a traveling clothing salesman, Robert Lee Scott Jr. was born in Waynesboro, Georgia, on April 12, 1908, and raised in Macon. He first expressed interest in air travel when he created a flying contraption using his grandfather’s wagon umbrella.

At 12, he built a makeshift glider from a canvas tent and knotty pine wood. “I cleared the first magnolia, but then the main wing strut broke, and I came down in Mrs. Napier’s rose bushes,” he once said. “It’s the only plane I ever crashed.”

The next year, he bought a ruin of a World War I Curtiss “Jenny” biplane at a public auction, sheltering it from his panicked parents in a friend’s garage. He made a deal with a mechanic to help him reassemble the craft in return for the mechanic’s shared use of the plane for barnstorming.

The man later died in a flying accident, but this did not seem to affect the future general’s ambitions. His head literally in the clouds, he had to repeat much of high school and could not get into the U.S. Military Academy at West Point through a congressional appointment. Instead, he enlisted in the Army and won a spot at West Point through a competitive examination.

After graduation in 1932, he flew the airmail “hell stretch” between New York and Chicago — known as a foggy, hilly and windy route that became more dangerous in rickety biplanes. He also built airfields in South America and was a flight instructor.

Desperate for new duty after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he managed to insert himself in combat operations despite being overage at 33. To do so, he lied about his experience flying four-engine bombers, claiming 1,100 hours when he had none. If he was going to invent facts, he said, he figured there was no use in being humble about it.

Luckily, a friend trained him in time for his mission, and then-Colonel Scott found his ticket to the Far East.

Initially scheduled to participate in a secret bombing raid over Japan, this was scuttled as the Japanese advanced over much of the Pacific. Instead, he settled in India as part of the Assam-Burma-China Ferry Command, flying food-and-supply transport missions over the Himalayas.

Through that work, he met General Claire L. Chennault, commander of the air defense group known as the “Flying Tigers.” He persuaded Chennault to lend him a P-40 combat plane to escort the supply missions.

From the start, he was masterful at knocking out the enemy, and in fall 1943 alone he was credited with at least 13 planes shot down and six more probable downings. He bombed strategic bridges and killed countless Japanese during hundreds of missions. Life magazine dubbed General Scott the “greatest of all the pursuit men.”

Although never shot down, he did suffer injuries. On one mission, bullets from a Japanese plane pierced his plane’s armor and drove metal into his back. Recuperating in a cave hideout, he was tended to by a medical missionary whose comments about someone looking out for the ailing flier gave meaning to the title of “God Is My Co-Pilot.”

Warner Bros. bought the film rights to the book, releasing a feature with Dennis Morgan as the nervy flier and Raymond Massey as Chennault. Critics were not kind, and neither was General Scott, who once said: “It was a bad movie. They had me talking by radio to the Japanese pilot and telling him, ‘Don’t call me Yank. I’m from Georgia.’ ”

He quietly returned to duty flying airplanes with experimental rockets aimed at destroying Japanese supply trains in eastern China and on Okinawa. After the war, he commanded the jet fighter school at Williams Air Force Base, in Arizona; was the Air Force director of information; and was commanding officer at Luke Air Force Base, also in Arizona, before retiring in 1957.

His military decorations included two awards each of the Silver Star and the Distinguished Flying Cross.

He briefly sold life insurance and devoted his time to lecturing and writing books. They included “Between the Elephant’s Eyes!” (1954), about his hunting expeditions in Africa; “Flying Tiger: Chennault of China” (1959); and “The Day I Owned the Sky” (1988).

He spent his final years fundraising for the Museum of Aviation at Robins Air Force Base, Georgiaa. He also, at age 72, walked much of the Great Wall of China, fueled by 1,400 homemade oatmeal cookies. He also brought along a golf club to help him walk and to use for protection, once telling a reporter, “I can kill anybody with a sand wedge, you know.”

His wife, Catharine Green Scott, whom he married in 1934, died in 1972.

Survivors include a daughter, Robin Fraser of Bakersfield, Califprnia; a sister; four grandchildren; eight great-grandchildren; and two great-great-grandchildren.

Retired Air Force Brigadier General Robert L. Scott, the World War II flying ace who told of his exploits in his book “God is My Co-Pilot,” died Monday. He was 97.

His death was announced by Paul Hibbitts, director of the Museum of Aviation at Robins Air Force Base, where Brig. Gen. Scott worked in recent years.

Brigadier General Scott rose to nationwide prominence during World War II as a fighter ace in the China-Burma-India theater, then with his best-selling 1943 book, made into a 1945 movie starring Dennis Morgan as Scott.

Among his other books were “The Day I Owned the Sky” and “Flying Tiger: Chennault of China.”

He exhibited the desire to fly at an early age. At 12, he flew a home-built glider off the roof of a three-story house in Macon, Georgia, and crash-landed in a flower bed.

“Gliders were built out of spruce, but I didn’t have enough money, so I made mine out of knotty pine,” he said. “I cleared the first magnolia, but then the main wing strut broke and I came down in Mrs. Napier’s rose bushes. It’s the only plane I ever crashed.”

Brigadier General Scott graduated from West Point as an Army Second Lieutenant in 1932 and completed pilot training a year later at Kelly Field, Texas. Before the war, he commanded a pursuit squadron in Panama, then instructed other pilots in Texas and California.

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, he was 33 — and considered too old for combat. But in March 1942, he volunteered for a secret mission, “lied” about being qualified to fly the B-17 bomber and met General Claire Chennault, the commander of the Flying Tigers.

Chennault was leading a group of volunteer fighter pilots battling the Japanese over China and Burma. When the unit was inducted into the U.S. Army in July 1942, Brigadier General Scott was named commander of the newly formed 23rd Fighter Group. By October 1943, he had flown 388 combat missions and had become one of the first U.S. air aces of the war.

He won three Distinguished Flying Crosses, two Silver Stars and five Air Medals before he was called home to travel the country giving speeches for the war effort.

The fighter ace later returned to the war, eventually downing a total of 22 enemy aircraft and hitting 10 supply trains before the war ended.

Brig. Gen. Scott later campaigned for separate service status for the Air Corps — a move that occurred in 1947 — and continued to lead fighter units in the United States and overseas. He commanded the nation’s first jet fighter school at Williams Air Force Base, Ariz., and later became the director of information for the Air Force.

He retired in 1957 with 36 years in uniform.

But in Brig. Gen. Scott’s case, retirement was nothing more than a transition. He continued speaking and writing, authoring at least 11 more books. From the mid-1980s onward, Brigadier General Scott also was active at the Robins air base’s aviation museum.

Brigadier General Scott leaves a daughter, Robin Fraser, of Bakersfield, California; a grandson; three granddaughters; and several great-grandchildren.

20 April 2006:

General Scott’s burial to be at Arlington in June

The burial of retired Brigadier General Robert L. Scott Jr., the World War II flying ace and best-selling author, will take place in Arlington National Cemetery on June 5, 2006, in a military service at 3 p.m., the Museum of Aviation at Robins Air Force Base announced Wednesday.

A native of Macon who grew up along Napier Avenue, Scott rose to nationwide prominence during World War II – first as a fighter ace in the China-Burma-India theater, then as author of “God Is My Co-Pilot,” an account of his wartime exploits.

The book was later made into a 1945 feature-length movie.

Scott, who retired from the Air Force as a brigadier general, never lost his “fighter ace” prominence and later used that fame to support the Museum of Aviation.

The war hero died March 27 at age 97 in a Warner Robins nursing home. The ashes of Scott and his wife, Katherine, who died in 1972, will be interred at the National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, next to thousands of other military veterans, officials said.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard