After Attacks, Community Rallies Around Principal

Support Helps Educator Who Lost Spouse September 11 Begin to Heal

It was early morning when the teachers at Hoffman-Boston Elementary School heard what they thought was a plane crashing in their South Arlington neighborhood. They felt the impact. They saw the smoke. They rushed into Principal Pat Hymel’s office.

“Call 911!” they shouted. “Call 911!”

Hymel ran out into the hall.

Minutes before, Hymel had heard about the attacks on the World Trade Center. She phoned her husband, Bob, a civilian management analyst at the Pentagon and half-jokingly asked, “How thick are the walls over there?” They laughed a little. She told him she loved him. She hung up the phone.

What happened in the following minutes and hours is a frantic blur for Hymel.

When she learned that what the teachers had heard was a plane crashing into the Pentagon, she did not have time to call her husband back. She kept her fears to herself.

For the next seven hours, she was consumed with one task: ensuring the safety and sanity of her 411 students. All of them were scared. All of them were unsure, like so many others around the nation, of exactly what was happening.

Ann Krug’s kindergarten class saw the plane crash outside the classroom’s window.

“I actually pointed it out and said: ‘Look at this plane; look at how low it’s flying,’ ” Krug recalled. “And then we all saw it come down.”

With Hymel leading the way, the staff corralled the children into the basement. They gathered blocks and books. They hauled three television sets down with them so they could keep the students entertained with educational videos.

“Her first priority was the students,” said Krug, who is also a close friend of the Hymels. “That was what needed to be done.”

Students remember their principal being strong and strict, yet still taking time to play with them. Everything seemed okay.

“Everyone was told that a plane had crashed and that everything was going to be all right,” Hymel recalled. “We hugged the children. We read to them. I could not let them know I was scared for my husband’s life. Taking care of them came first.”

Soon after the attacks, parents started arriving at the school to pick up their children. And Hymel, along with Ilsa Reyes, school counselor, had to walk each student up the stairs from the basement to the school’s office.

This went on for hours. Up and down. Back and forth.

“At one point, Pat did say, ‘You know, Ilsa, I can’t worry about my personal life,’ ” Reyes said. “She really tried not to think about it.”

Hymel did not cry. She did not let anyone, especially the students, think that she was worried. That was, until the last child was picked up at 6:45 p.m.

Finally, she turned to Reyes and Krug and said: “Okay. Help me. Help me see if he is alive.”

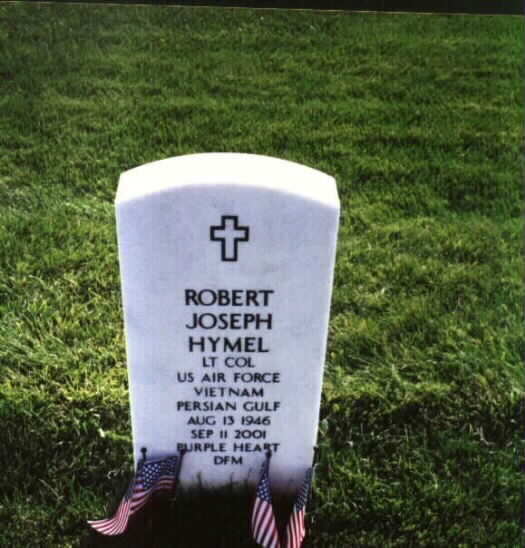

Hours later, Hymel learned from the Pentagon that her husband, retired Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Robert J. Hymel, 55, was one of those killed in the September 11 terrorist attack on the Pentagon.

Coming Together

In the days and weeks after the attack, a community-wide effort to thank Hymel for putting the children before her own worries — and help her deal with her own pain — sprouted. The outpouring of support was so vast that Hymel began to feel like she was at least starting to heal.

The food came first — plates and plates of food donated to the Hymel family from teachers and local families.

“We just started cooking and providing the meals,” Krug said. “We would bring trays and trays of food over.”

Community residents started calling each other, wondering what to do. There were flowers and cards — hundreds of them. Many students asked to make them in classes. Hymel keeps the cards in a straw basket in her office.

“For a little while [students] were drawing these pictures with extreme sadness with no smiling faces and colors that had madness,” said Alicia Kopec, an art teacher at the school. “But then they started to write her cards and the pictures and images switched.”

Mercedes Wilson, 10, drew pictures of flowers and the sun.

“The whole school wants to cheer her up,” said Mercedes as she played in the schoolyard on a recent day. “We want to make her happy.”

Adults also wrote cards; some wrote several. Patti Macie, who coordinates the extended-day programs for Arlington County schools, wrote four.

“To me, Pat was like this little Mighty Mouse,” Macie said, describing the 5-foot-2 dynamo with curly black hair.

“She was just this strong, energetic person.”

The school also planted a garden and placed American flags around it. And there is a blood drive planned for December 5 in Robert Hymel’s memory.

Local residents and other schools have donated about $5,000 in a fund set up for the school in Robert Hymel’s name. Ninety percent of Hoffman-Boston’s students qualify for free and reduced lunch — an indicator of poverty. Schools from across the country have sent mittens, teddy bears and other gifts to the Hoffman-Boston students.

A Love Story

Hymel was extremely close to her husband. They met in Del Rio, Texas, when he was going through pilot training at Laughlin Air Force Base in 1969.

She did not like him at first. Hymel was interested in taller men, and Robert stood 5 feet 6 inches. He was undeterred, however. “Unrelenting,” Pat Hymel recalled.

She was part Mexican American and Jewish. He was of Cajun descent. The two shared their cultures, cooking for each other and taking trips to his native Louisiana.

The Hymels married 30 years ago and have a grown daughter, Natalie, and a 3-year-old granddaughter, Lauren.

When Natalie was a teenager, she would roll her eyes when her parents would hold hands in public. Even after 30 years, the couple acted like school kids in love.

“It was the type of marriage where he would turn to me sometimes and tell me I looked beautiful,” Pat Hymel recalled. “I would say, ‘Come on,’ and he would say, ‘No, I am falling in love with you all over again.’ “

The marriage was a “real partnership,” she said. She recalled how he had decided to take the Pentagon job so she would have a chance to pursue her dreams.

“For years and years, I was the military wife, moving 15 times, teaching in school districts everywhere,” she said. “The last few years he said it was my time. It my chance to be a principal and he would make dinner for me when I came home. It was really a fair exchange.”

Robert Hymel made himself known around Hoffman-Boston.

To students, he was the man with the mustache who brought them ice cream and came to their math and science nights. He was not just their principal’s husband; he was someone they recognized in the halls.

What do children do when they see an adult in pain? How did they cope with such a thing?

Many of the children reacted simply. First, they asked to attend a special funeral for Robert Hymel. For many of the students, it was their first time at a memorial service.

“I wanted to go,” said Olivia Green, 7. “I wanted to hug her and hug her.”

“I felt I should go,” said Julian Giovanetti, 10. “She’s just a nice lady. She’s always telling me to do my homework and pushing me to the next grade. I mean, if someone in my family had died, I would want her there.”

In fact, hundreds of people, many of them young students, sat on the grass outside Arlington National Cemetery last month to watch a special public memorial observance for Robert Hymel.

A B-52 bomber flew over the cemetery, a special act requested by his wife because it was the second time that Robert Hymel had been caught up in an extraordinary aircraft incident.

Hymel was a B-52 co-pilot during the Vietnam War. In December 1972, his plane was hit by a missile over Hanoi. When the crew tried to land the plane, it pulled sharply to the left. On a second attempt, the B-52 “fell out of the sky,” Pat Hymel said.

Hymel was pulled from the plane. He was just 20 feet away when it burst into flames. He suffered from collapsed lungs and a crushed arm. Last rites were administered. His wife said his doctors were astonished at his recovery and attributed his survival to his desire to live to meet his daughter, then 2 months old. Three members of the five-man crew perished. Hymel was awarded the Purple Heart.

Pat Hymel, who came in to work for at least a few hours each day in the days after her husband’s death, said the kindness the community has shown has made a difference to her.

Her mentor, Larry Grove, a former Arlington principal, came in to help run the school while she took some time off.

Still, Hymel said she yearned to be back and feel the buzz of her school.

“I thank God for my job,” she said, as she stood in the schoolyard, telling a group of boys to stop teasing some girls. “Everyone here really has helped me through.”

With that she went back inside, and a few kids tugged at her leg and a few teachers stopped her in the hall with questions and a few parents waited to talk to her in the office. It was time for her to once again focus on her school.

And for that, she was thankful.

undreds Watch B-52 Bomber Roar Over Arlington Cemetery

Flight Honoring Pentagon Attack Victim Stirs Pride, Not Panic

Far from causing alarm, the flight of a B-52 bomber over Arlington National Cemetery yesterday turned into a public memorial observance as hundreds of people stopped their cars or sat on the grass outside the cemetery to watch.

The well-publicized flyover was part of the funeral service for retired Air Force Lieuenant Colonel Robert J. Hymel, 55, one of the victims of the September 11 terrorist attack on the Pentagon.

A civilian management analyst at the time of his death, Hymel was a B-52 co-pilot during the Vietnam War.

As the bomber flew toward the cemetery about 3:25 p.m., it tipped its wings slightly toward the crowd, seeming to acknowledge the spectators who had gathered to take pictures.

Fearing that people would be anxious at the sight of a military plane, the military took pains to get word out about the flyover by the eight-engine aircraft.

But for many, the warning became a reason to visit the cemetery on a warm, sunny fall day — and police, though present, didn’t issue tickets or object to double-parked vehicles until the plane was out of sight, on its way to Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota.

Some spectators said they felt they were paying homage to all the victims of the attacks.

“I’m feeling so patriotic right now,” said Charlie Blaschke, who drove from Fairfax City with his wife, Barbara.

“It’s something you don’t get to see very often,” Barbara Blaschke said. “I think this whole thing has kind of left a hole in everybody’s heart.”

Hymel stopped flying in 1972 after being gravely injured when his plane was hit over Hanoi and three members of the five-man crew were killed. His wife, Beatriz “Pat” Hymel, principal of Hoffman-Boston Elementary School in Arlington, said she had requested the flyover and was “ecstatic” that the military agreed.

Mimi Parikh and Kathy Giles, friends who had spent the afternoon visiting the Corcoran Gallery of Art in the District, decided to walk across Memorial Bridge to see the flyover. “It makes you appreciate being in D.C.,” Parikh said. “You appreciate seeing stuff like that.”

Debbie and Curt Young came from Vienna and parked near the bridge to see the flyover. Curt Young, an Air Force lieutenant colonel working at the State Department, used to fly B-52s.

“It’s really special that they were able to make this happen,” Debbie Young said, adding that they were surprised at first to see so many other people waiting, too.

“But I think people are pulling together so closely after this,” Curt Young said.

A B-52 bomber will fly low over Arlington National Cemetery as part of a funeral today, a highly unusual event that could be frightening for any nearby residents not forewarned, Arlington County and Air Force officials cautioned.

The eight-engine plane will pass over the area at 3 p.m. at an altitude of about 1,000 feet. It will approach from the Potomac River and the Pentagon before heading over Arlington Cemetery and continuing west to its home at Minot Air Force Base, North Dakota, Air Force officials said.

The military put out word of the flyover Thursday.

“Much consideration was given to potential public anxieties, which is why additional notification . . . was made,” said Major Cheryl Law, an Air Force spokeswoman.

Flyovers at Arlington occur seven or eight times a year and are usually reserved for pilots and aviators who died on active duty, cemetery historian Tom Sherlock said. Sherlock said he knew of only three other B-52 flyovers in the past 25 years.

The funeral is for retired Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Robert J. Hymel, 55, a victim of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. Hymel, a civilian management analyst, was working in the Pentagon when a hijacked airliner struck it. It was the second time he had been caught up in an extraordinary aircraft incident.

Hymel was a B-52 co-pilot during the Vietnam War. In December 1972, his plane was hit by a missile over Hanoi. When the crew tried to land the plane, it pulled sharply to the left. On a second attempt, the B-52 “fell out of the sky,” said Beatriz “Pat” Hymel, his wife.

The crew had elected not to bail out, Hymel said, because it had lost contact with the plane’s wounded gunner. When the plane crashed, the gunner managed to get out and survived.

Hymel was pulled from the plane and saw it burst into flames when he was just 20 feet away. He had collapsed lungs and a crushed arm and was administered last rites. His wife said his doctors were astonished at his recovery and attributed it to the fact that he wanted to meet his daughter, then 2 months old.

The other three members of the five-man crew perished. Hymel was awarded the Purple Heart.

“I’m eternally grateful that God gave him to me for 29 more years,” said Pat Hymel, who is principal of Hoffman-Boston Elementary School in Arlington. She requested the flyover and said she was “ecstatic” that the military granted it.

“My husband always regretted not being able to go back to flying,” she said, a limitation caused by his inability to fully extend his left arm.

The B-52 Stratofortress, a long-range, heavy bomber, has a takeoff weight of up to 488,000 pounds, according to the Air Force. It has a wingspan of 185 feet and can fly as high as 50,000 feet. The bomber, first flown in 1954, ceased production in 1962. The 94 planes still in service have been renovated and upgraded, an Air Force spokesman said, and are expected to remain in operation beyond 2045, becoming one of the longest-serving weapons in U.S. history.

B-52s dropped 40 percent of all bombs used by coalition forces during Operation Desert Storm and are involved in the bombing campaign in Afghanistan.

Robert Hymel

Attack Location: Pentagon

Age: 55

Home: Woodbridge, Virginia

Beatriz “Pat” Hymel met her husband, Robert, in Del Rio, Texas, when he was going through pilot training at Laughlin Air Force Base. It wasn’t love at first sight — Hymel was interested in taller men, and Robert stood 5 feet 6 inches.

He was undeterred, however. “Unrelenting,” Pat Hymel, principal of Arlington’s Hoffman-Boston Elementary School, said with a laugh. The Hymels married 30 years ago and have a daughter, Natalie, and a 3-year-old granddaughter, Lauren.

Robert Hymel, 55, a Louisiana native, was working at the Pentagon as a civilian management analyst. He had retired from the Air Force as a lieutenant colonel. He served in Vietnam during the war there and was awarded the Purple Heart.

The Hymels’ Woodbridge neighborhood has embraced the family since his name was added to the list of Defense Department employees missing at the Pentagon.

Neighborhood children bring over cookies. Neighbors have put out flags. Friends in Arlington also have rallied around the family.

Pat Hymel said she’s grateful for the 30 years with Robert. Early in their marriage, he was shot down over Hanoi in his B-52. Grievously injured, he was given last rites, but he survived.

“Other people in that plane died,” Hymel said. “We had him for 29 more years. I can’t be angry.”

— Christina A. Samuels

HYMEL, ROBERT JOSEPH (Age 55)

Of Lake Ridge, Virginia, on Tuesday, September 11, 2001, at The Pentagon. Beloved husband of Beatriz ”Pat” Hymel; devoted father of Natalie (Patrick) Conners of Manassas, VA; son of Elsie Hymel and brother of Mary Toce, both of Lafayette, LA and Clyde Hymel of Fort Worth, TX; beloved grandfather of Lauren Conners of Manassas, VA.

Robert was a Management Analyst with DIA for the past seven years. He was a retired Lieutenant Colonel for the US Air Force, serving in the Vietnam War. Among the decorations he received were the Purple Heart, Flying Cross and the Air Medal. Friends may call at St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church, 12805 Valleywood Dr., Woodbridge, VA on Saturday, October 13 from 12:15 to 1 p.m., and where Mass of Christian Burial will be held at 1 p.m. Interment with Full Military Honors will be held at Arlington National Cemetery at 3 p.m. In lieu of flowers, contributions may be made to Hoffman-Boston Elementary School, 1415 S. Queen St., Arlington, VA 22204.

It was Christmas Day 1972 and the bombers were idle, but Air Force Lieutenant Bob Hymel was feeling uneasy.

The B-52 crews based at U Tapao in Thailand were in the midst of an intense bombing campaign of North Vietnam known as Linebacker II, ordered by President Richard Nixon to force the communist government to resume negotiations. With anti-war feeling high back home, Nixon had ordered a Christmas Day bombing pause.

“It was extremely tense for everyone,” Hymel recalled in a 1976 interview for a book on the bombing campaign. “We were concerned about the Christmas bombing halt; afraid that the North Vietnamese had used the halt to restock and repair their SAM [surface-to-air missile] facilities.”

They were right.

When the bombing resumed the next day and his crew flew toward its target, a warehouse complex northwest of Hanoi, Hymel, the co-pilot, could hear on the radio that planes ahead were getting “hosed down” with Soviet-supplied missiles. One B-52 struck by a missile exploded in midair.

As Hymel’s plane dropped its bombs and rolled off the target, the gunner called out a warning about approaching missiles.

Turning his head, Hymel saw two SAMs coming up side by side, turn directly toward the B-52 and explode along the plane’s right side. “It felt as though we had been kicked in the pants,” he said.

Two engines had been knocked out, fuel was leaking and the gunner was wounded.

The crew could have ditched the plane over water, but the pilots were unable to communicate with the gunner and were unsure whether he would be able to bail out. They decided to fly the big crippled plane to U Tapao.

On the approach to the airfield, the plane suddenly veered to the left, and the pilot was unable to regain control.

Captain Brent Diefenbach, a B-52 pilot on the ground, watched as the plane pitched up and then fell to the ground, exploding in flames. “Nobody survived that one — that’s what I thought,” said Diefenbach, who lives in Fairfax Station.

Diefenbach raced to the scene, running through tall elephant grass to the inferno, arriving before rescue crews. To his shock, he heard a faint call for help. It was Bob Hymel.

“He was so stuck in there, it was just a mess,” Diefenbach said. “Things were blowing up, and it was time to go.” Diefenbach managed to cut Hymel loose and drag him to safety. Four crew members died.

Hymel, who suffered multiple broken bones and crushed vertebrae, was in the hospital for 1 1/2 years and never went back to flying, but he stayed in the Air Force for 20 more years.

“It used to bug him that he survived and the others died,” Pat Hymel said. “He was driven. I saw a change in his personality: ‘Okay, I’ve been given a second chance, so I’m going to make the most of it.’ “

After retiring from the Air Force seven years ago, Hymel went to work as a civilian for the Defense Intelligence Agency in the Pentagon.

During Hymel’s funeral in October, a B-52 flew over Arlington National Cemetery and dipped its wings, a rare honor.

NOTE: Colonel Hymel was laid to rest in Section 64 of Arlington National Cemetery, in the shadows of the Pentagon.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard