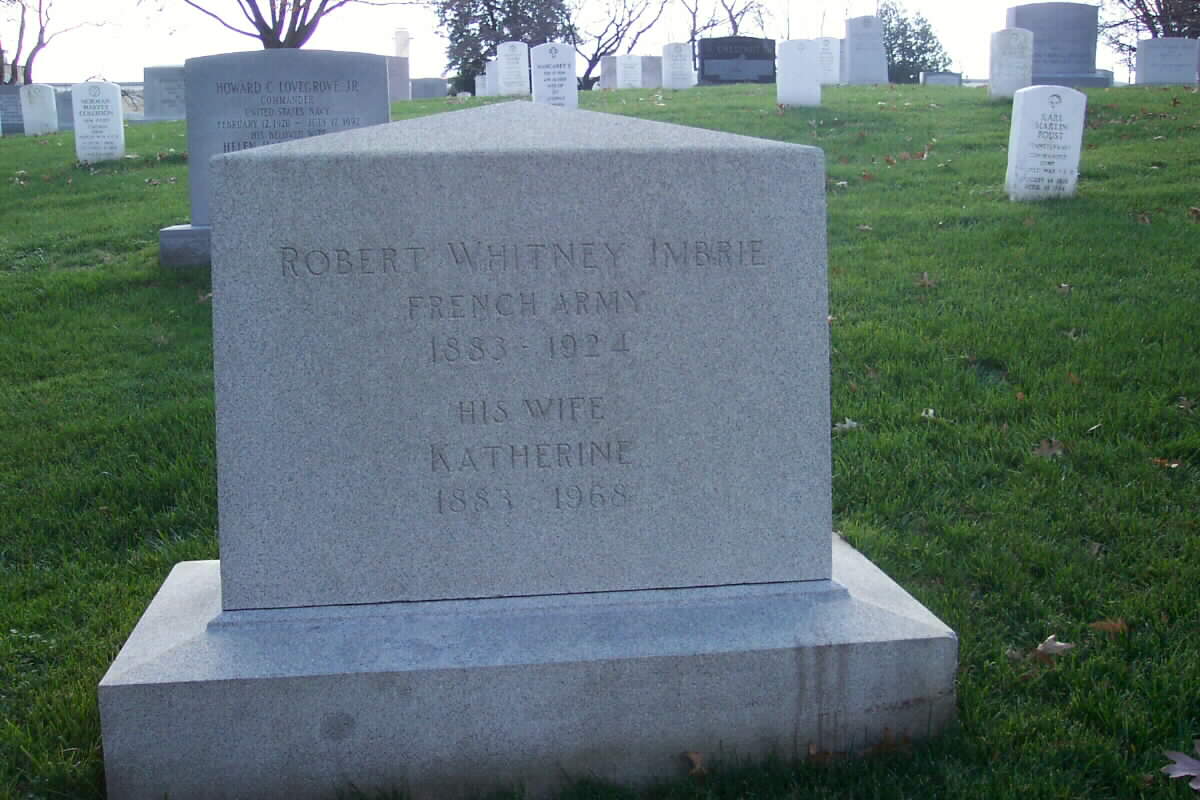

No rank on headstone

French Army

Killed at Teheran, Persia, July 18,1924

In the Foreign Service

1883-1924

Katherine Imbrie, Wife of Robert Whitney Imbrie

1883-1968

These are two brief articles describing the 1924 murder of an American diplomat by a Muslim mob who thought he was a Baha’i. New York Times July 24, 1924.

IMBRIE MURDER LAID TO RELIGIOUS HATE

Blindness of a Moslem and Poisoning of Sacred Well Ascribed to Baha’is.

AMERICAN LINKED WITH SECT

Vice Consul Beaten to Death in Hospital Operating Room, Had Forty Wounds.

TEHERAN, July 23, 1924. – The following are the events which led up to the murder of Major Imbrie, American Vice Consul here. About a month ago a native was rumored to have lost his sight at a well immediately after having uttered the name of Abbas Effendi, the late spiritual leader of the Bahais. The well thereupon became a shrine and was visited by crowds of Moslems, who started anti-Bahai demonstrations without any attempt by the authorities to stop them.

A few days ago the well was said to have been poisoned and Bahais were reported to have done it. Attempts were made to find the alleged culprits and the place became still more crowded. On Friday morning Major Imbrie and Seymour, his companion, visited the place to take photographs. They were warned not to approach the well, as women were present.

Accordingly, they desisted and entered their carriage. Then shouts were raised that they were the Bahais who had poisoned the well. Stones were thrown, and the carriage was followed by a crowd. Finally it was stopped and the two Americans were dragged out and attacked by the mob with sticks and stones. Soldiers were seen in the crowd and the police made only feeble efforts to rescue the Americans.

Major Imbrie, who was unarmed, did his best to defend himself until he became unconscious from a blow on the skull, evidently delivered with a sabre. While he was lying on the ground a stone broke his jaw. He was finally carried to the police hospital, but the mob forced its way into the operating room and continued to attack him. He received more than forty wounds.

While this disgraceful outburst on the part of a fanatical mob and the total inadequacy of the measures taken by the police have proved the existence of a danger to foreigners against which the Diplomatic Corps has strongly protested and demanded the enactment of proper measures for the security of foreigners and members of religious minorities, the steps already taken by the Persian Government have, it is hoped, removed for the present any reason for fearing a general outbreak of violence against foreigners.

The existence of martial law gives to the government power to prevent the publication of any more anti- foreign, particularly anti-British, articles in the press. Many of these, notwithstanding continued protests by the legation, have been published of late and have inflamed the excitement of the ignorant masses. It is difficult to absolve the government from all blame, as it has full control over the army, yet presumably from reasons of internal politics it has done nothing to check the effervescence.

It is hoped that the Government has now received a salutary lesson in this outrage and has learned that if it desires to gain the sympathy of the civilized powers it must govern in a civilized manner and cease to resort to appeals to the fanatical instincts which permeate not only the mob but also a large proportion of the intelligentsia. Eulogies in the Persian press about the courageous conduct of the police and soldiers are seriously discounted by the fact, according to various witnesses, that soldiers took part in attacking MajorImbrie and that the wound on his skull could have been made only by a sabre such as the soldiers carry.

WASHINGTON, July 23. – State Department advises from Teheran indicate an absence of premeditation in the killing of Vice Consul Imbrie and, it was announced today, the department will await further data before any official action is taken. Latest reports from Minister Hornfeld said there appeared to be no cause for anxiety regarding the welfare of foreigners in Persia and that tranquillity prevailed. the message added, that Teheran was under martial law and no reports of disturbances in the provinces had been received.

Buried with fill military honored in Arlington National Cemetery (Section 4, 2903 (Major, FR)

Even before the United States entered World War I, some young men signed up with the volunteer ambulance corps, which recruited college students and recent graduates to serve on the French and Italian fronts. Among them were such later famous writers as e. e. cummings, Dashiell Hammett, John Dos Passos, and Ernest Hemingway. Not surprisingly, many of these former ambulance drivers later wrote about their experiences in memoirs and novels. In this passage, from a book-length memoir, Robert Whitney Imbrie writes in a humorous vein of the bond of affection and loyalty between an ambulance driver and his car.

THE GUNS THAT COMMAND MONASTIR

THOUGH most of the houses were closed and shuttered as protection against shell splinters, life seemed to go on much as usual. There was no traffic in the streets, save at night when the army transports came through, or when our machines went by with their loads, but the populace passed and repassed, bartered and ordered its life with the phlegmatic fatalism of the Easterner. The enemy from his point of vantage saw every move in the city. His guns commanded its every corner. His surveys gave him the range to an inch. Daily he raked it with shrapnel and pounded it with high-explosive. No man in Monastir, seeing the morning’s sun, but knew that, ere it set, his own might sink. At any time of the day or night the screeching death might come, did come. Old men, old women, little children, were blown to bits, houses were demolished, and yet, because it was decreed by Allah, it was inexorable. The civil population went its way. Of course, when shells came in there was terror, panic, a wailing and gnashing of teeth, for not even the fatalism of Mohammed could be proof against such sights. And horrible sights these were. It was nothing to go through the streets after a bombardment and see mangled and torn bodies; a man with his head blown off; a little girl dead, her face staring upward, her body pierced by a dozen wounds; a group in grotesque attitudes, with, perhaps, an arm or a leg torn off and thrown fifty feet away. These in Monastir were daily sights.

One afternoon I remember as typical. It was within a few days of Christmas, though there was little of Yuletide in the atmosphere. At home, the cars were bearing the signs, “Do Your Christmas Shopping Early,” but here in Monastir, where, as “Doc” says, “a chap was liable to start out full of peace and good will and come back full of shrapnel and shell splinters,” there was little inducement to do Christmas shopping. Nevertheless, we started on one of those prowling strolls in which we both delighted. We rambled through the tangled streets, poked into various odd little shops in quest of the curious, dropped into a hot milk booth where we talked with some English-speaking Montenegrins, and then finally crossed one of the rickety wooden bridges which span the city’s bisecting stream. By easy stages, stopping often to probe for curios, we reached the main street of the city. Here at a queer little bakery, where the proprietor shoved his products into a yawning stove-oven with a twelve-foot wooden shovel, we got, for an outrageous price, some sad little cakes. As we munched these, we stood on a corner and watched the scene about us. It was a fine day, the first sunny one we had experienced in a long time. Many people were in the streets, a crowd such as only war and the Orient could produce: a sprinkling of soldiers, mostly French, although occasionally a Russian or an Italian was noticed; a meditative old Turk, stolid Serbian women, little children — a lively, varied picture. Our cakes consumed, “Doc” and I crossed the street and, a short way along a transverse street, stopped to watch the bread line. There were possibly three hundred people, mostly women, gathered here waiting for the distribution of the farina issued by the military to the civil population. For a while we watched them, and then, as the street ahead looked as if it might yield something interesting in booths, we continued along it. In another fifty yards, however, its character changed; it became residential, and so we turned to retrace our steps. Fortunate for us it was that we made the decision. We had gone back perhaps a dekametre, when we heard the screech. We sprang to the left-hand wall and flattened ourselves against it as the crash came. It was a “155” H.E.. Just beyond, at the point toward which we had been making our way, the whole street rose into the air. We sped around the corner to the main street. It was a mass of screaming, terror-stricken people. In quick succession three more shells came in, one knocking “Doc” off his feet with its concussion. The wall by which we had stood and an iron shutter close by were rent and torn with éclats. One of these shells had struck near the bread line. How many were killed I never knew. “Doc” for the moment had disappeared, and I was greatly worried until I saw him emerge from an archway. There was now a lull in the shelling. All our desire for wandering about the city had ceased. We started back toward quarters. Before we were halfway there, more shells came in, scattered about the city, though the region about the main street seemed to be suffering most. Crossing the stream, we saw the body of a man hanging half over the wall and near by, the shattered paving where the shell had struck.

In such an atmosphere we lived. Each day brought its messages of death. On December 19, I saw a spy taken out to be shot. On the 20th, a house next our quarters was hit. Two days later, when evacuating under shrapnel fire, I saw two men killed. Constantly we had to’ change our route through the city because of buildings blown into the street.

ROBERT WHITNEY IMBRIE*

*From Behind the Wheel of a War Ambulance. Courtesy of Robert M. McBride & Company of New York.

Report to the U.S. Secretary of State

by W. Smith Murray

American Consular Service,

Teheran, Persia

August 10, 1924

[stamped: FILED NO V 14 1924 N]

[stamped: ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF STATE OCT 14 1924 A-3]

[stamped: Department of State Oct 13 1924 Division of Near Eastern Affairs]

[stamped: UNDER SECRETARY, OCT 2 1924 DEPT. OF STATE]

[stamped: ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF STATE OCT 16 1924 A-4]

[handwritten: Instruction Drafted 10/6/24 accepted.stamped beneath: October 13 1924] [stamped: No. ? INDEX BUREAU Rec’d OCT 13 1924 Dept. of State]

[stamped: INDEX BUREAU; handwritten over stamp: P.B. 123 ? / 298]

[stamped: DEP T. OF STATE NOV 12 1924 Division of Foreign Service Administration]

SECRET AND STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL

The Honorable The Secretary of State, Washington

Sir: – I have the honor to bring to the attention of the Department CERTAIN PHASES OF THE MURDEROUS ASSAULT WHICH CULMINATED IN THE DEATH OF VICE CONSUL ROBERT WHITNEY IMBRIE IN TEHERAN on July 18, 1924, which, it is my impression, have not yet been communicated to the Department and which, I trust, will be of assistance in clarifying in some degree the circumstances surrounding the tragedy.

It is generally admitted that the killing of Major Imbrie was attended with a viciousness and savagery practically unknown in latterday Persian history; the Persians have not been slow to point out that their race has not, in the past, been given to violence and that even during the turmoil of the Persian Revolution of 1906 the greatest self-control was exhibited in order not to harm in any way foreign residents of the country. This fact makes the crime all the more remarkable and the necessity for penetrating into its deeper significance all the more imperative.

It is to be noted that the so-called miracle which took place in Teheran some two weeks previous to the assault was universally regarded by all Europeans and by most intelligent Persians as an absurdity, and there could not have been the slightest reason to believe that a visit to that “sacred” spot would incur any danger. It is furthermore to be noted that the all eged attempt on the part of Major Imbrie to take photographs at the Sakheh Khaneh could in no way be ascribed as the motive for the murderous attack at the Kossak Khaneh, inasmuch as the latter is more than a mile away from the former and the mob, numbering more than two thousand persons, which gathered as the carriage proceeded to the latter point, could not possibly have been informed of the photographing episode; hence the latter cannot be presumed to have inflamed the mob.

It is of extraordinary significance that the attacks upon Major Imbrie and Mr. Seymour should have taken place – first, directly in front of the large entrance to the Kossak Khaneh within a few feet of the guardhouse at the gate, and second, upon the operation tables of the Police Headquarters Hospital, which is perhaps not more than a few hundred yards from the gate of the Kossak Khaneh.

That the Government’s case in the affair is totally nil and nonexistent ill be observed from the following points: –

1. Although the situation in Teheran since the collapse of the republican movement has, with regard to law and order, been a critical one, and although the Government might have realized the seriousness at this time of the Sakheh Khaneh demonstrations, the Prime Minister admits that he had issued orders, previous to the tragedy, that both the police and military should abstain from intervention of any kind in religious demonstrations and that under no circumstances was a shot to be fired; hence the situation of two men, attacked by a mob of two thousand fanatics, left to their fate.

2. Although the attack upon Imbrie and Seymour lasted about half and hour, at a spot within a stone’s throw of both the Police Headquarters and the Kossak Khaneh, where both police and military reserves were at hand, no attempt was made to intimidate the mob.

3. The participation of the military and of at least one officer in the assault is an incontrovertible fact. This has been verified in the first deposition taken from Seymour, in which he stoutly affirmed that the officer-of-the-day was one of the first to strike him. Furthermore, I was confidentially informed by an officer of the Persian Army, who was an intimate friend of mine, that he was personally acquainted with the officer-of-the-day in charge of the guard at the gate, one Lieutenant Janmamad, and that the latter had freely confessed to him that not only the men in his charge on the fatal morning had rushed out and joined in the attack, but that he himself had participated. When questioned as to why he did do, he said, “I had no idea it was the American Consul. I thought it was a dog of a Bahá’í.”

At this point it is well to cite the following proofs that his identity was known to some, at least, of his assailants: –

a) When Major Imbrie’s carriage was stopped at the gate of the Kossak Khaneh, he drew out his card and handed it to a police officer, stating that he was the American Consul and that he could be seen at any time at the American Consulate.

b) Major Imbrie was accompanied by a “kavass” of the American Consulate, wearing the American insignia on his hat and buttons and coat. Both the insignia and buttons were ripped off early in the attack by someone who would appear to have extraordinary presence of mind.

c) When Seymour was dragged from the carriage, which had already passed through the Kossak Khaneh gate, he was asked by the officer-of-the-day who he was and where he was going. He stated, “I am an American, and I want to go to the American Consulate”; whereupon the officer struck him, saying, “I think you will be living here for a while.”

d) As the Department will have already noted in the deposition of Issak, the Chaldean servant of Doctor Packard, who was at the scene of the assault, the latter shouted repeatedly to the mob, to the military, and to the police, that they were killing the American Consul and that he was not a Bahá’í. Hence, the fiction that there could have any misapprehension as to the person upon whom the violence of the mob was being vented is totally exploded.

To return now to the officer-of-the-day, Lieutenant Janmamad, I believe the Department will agree with me that the government showed a reprehensible negligence in that his arrest was not immediately ordered after the tragedy, inasmuch as it stands to reason that he and his men, given the fact that the incident happened before his very door, could not but have been at least cognizant of it. It was not until July 26, eight days later, that his arrest was promised, after I had demanded it. It is furthermore to be noted that his name does not occur in the police report of the crime, made on July 26, and that on august 7, when I called the matter to the attention of the Foreign Minister he seemed surprised that he had heard nothing of it and, after noting it down, promised to take immediate action. although there appears to be ample evidence that a considerable number of the military participated in the attack, only one soldier, named Morteza, of the Army Transport, had by July 26 been arrested, and apparently none of the guard of the day. The police report of the above mentioned date states, “Several other soldiers have also, according to investigations made, taken part in the beating and insulting. The Emergency Commission is searching for them.”

The American Minister, shortly after the murder, received authoritative information, to the effect that Reza Khan had threatened “to cut the tongue out of any officer or man who opened his mouth with regard to the affair.” That is was his original determination to shield the military is furthermore evident from a conversation which he had about the same time with Mr. Soppier, the Sinclair representative, in which he flew into a rage at a suggestion of the latter that the military were involved.

4. When, finally, Imbrie and Seymour were rescued by the police and placed in an automobile to be transported to the hospital, the authorities were either unwilling or unable to prevent the crowd from beating and assaulting the senseless men in the automobile.

5. When the two Americans finally reached the hospital and had been carried to the operation tables, the police authorities, in their own headquarters, were again either unwilling or unable to prevent the storming of the hospital by the savage mob, which was led by Seyed Hossein, followed directly by a group of Cossacks with drawn swords.

I, myself, through Dr. Packard, heard the statement of one Ali, the hospital attendant who was present when the wounded men were brought in, and who stated that he was unable to prevent the mob from entering the operation room. He showed me the tiles of the floor which had been torn up and shattered on the body of Imbrie, as well as a chair which was smashed in assaulting him. Although Seymour was lying in a room through which the mob had to pass, he was spared further assault because the mob was told that he was dead.

The Department is already in possession of the deposition which I took from doctor Jalal Shaffa, one of the native physicians at the American Hospital, who was one of the first to arrive at the Police Hospital and to whom a policeman present volunteered the information that he was unable to hold back the mob because they were led by Cossacks, armed with sabres. The truth of this statement was, on the same day, verified by the admission of Lieutenant Nehmattollah, a police officer on the Investigation Commission, to the effect that the latter attack was led by Cossacks, but that they were fired to vengeance by Seyed Hossein, crying that he would “have the blood of this infidel dog to avenge the death of Hossein and his grandfather.”

FOREIGN POLITICAL BACKGROUND

Almost simultaneously with the killing, the rumor arose in the city that it was the result of oil intrigues and that the mob believed it had got Soper, the Sinclair representative. In this connection I may state that such was apparently the belief of the authorities at the hospital upon the arrival of Mrs. Imbrie, inasmuch as they refused permission to her and Doctor Packard to enter and insisted that Imbrie was not her husband.

Almost immediately also, the hue and cry against the British was taken up in the Persian press, and it was openly intimated that they were responsible for the crime. In this connection, I have positive information that it is the firm conviction of the Prime Minister that the British are responsible for the encouragement and subsidizing of the Sakheh Khaneh storm center, if not for the actual crime itself.

On the day of Major Imbrie’s funeral the British Charge d’Affaires, Mr. Esmond Ovey, who had already gotten wind of the above rumors, solemnly warned Zoka-ol-Molk, the Foreign Minister, that the control of the press must be tightened and that he would not tolerate any publication of such rumors. The warning was apparently ineffective inasmuch as the next few days brought a torrent of abuse and the vilest insinuations agai nst “the land of the lion and the unicorn.”

Thereupon the British Charge rushed, with his oriental secretary,

Mr. Harvard, to the Prime Minister’s country house, and delivered an ultimatum to him, that categorical instructions be issued to suppress any paper in Teheran intimating Great Britain’s participation in the affair. The Prime Minister was at first obdurate and stated that the whole matter would first have to be investigated; but he finally yielded and published a dementi, after which the situation, as far as the British were concerned, was for the moment relieved.

Another and still more tense situation was created, however, when the Persian authorities attempted a few days later to arrest Mostafa Khan, the Persian private secretary of Mr. W. C. Fairley, the Anglo-Persian representative in Teheran. The attempt was met by a still more vigorous intervention on the part of Mr. Ovey, who told Reza Khan that any such act on his part would be regarded by the British Government as proof positive that he considered the rumors concerning the British true.

I may state at this point that the young man in question, Mostafa Khan, a graduate of Columbia University and pretended friend of America, is positively known to have engaged, for the sake of his employer, in the most unsavory and unwarranted attacks on everything American, in order to prevent at all costs the passage of the Sinclair oil bill. I am reliably informed that he has, during the last critical days, offered to several members of the Mejliss, whose names are known to me, a bribe of eight tomans a month, if they will abstain from their duties and thus break the quorum. I furthermore know that he approached the Deputy from Isfahan and used the novel argument, as to why he should vote against the oil bill, that the American people, “enraged at the treason of the late President Harding for having sold them out to the Sinclair Oil Company,” had torn open his grave and burned his body. This is the man who, though a Persian subject, enjoys the protection of the British Legation.

It was clear from the outset that the Russians intended to leave no stone unturned in order to push the responsibility for the crime into the shoes of the British. On the day of the funeral one of the Secretaries of the Bolshevist Legation, Mr. Walden, stated to a personal friend of mine, Mr. Swiminoff, who was educated and has lived many years in America, that the whole thing had been engineered by the British in order to prevent passage of the oil bill. Both the local Persian press, enjoying the Russian subsidy, as well as the organ of the Russian Telegraphic Agency, “Rosta”, launched a violent campaign against the British, containing open accusation. The British Charge d’Affairs immediately wired for instructions to London, and thereafter called upon the Russian Minister, and, after a three and a half hours’ conference, was unable to persuade him to make a frank retraction of these statements. The best that could be done was a half-hearted statement on the following day in the “Rosta”, to the effect that the published reports “were not the individual opinions of the editor.”

As I pointed out to the Department in my telegram No. 8 of July 29, the attitude of the Russians with regard to the affair was fully clarified by their behavior in the three meetings of the Diplomatic Corps which followed the murder.

In the first, they strongly objected to any reference whatsoever to the military, as having participated, and insisted, in addition, that the minorities clause be added, condemning religious fanaticism.

In the second, they moved that the Diplomatic Corps unanimously accept the Government’s reply to the protest drawn up in the first meeting, despite the fact that this body was therein informed that its protest was unjustified. After vainly attempting to block any further conferences, the Russian Delegation rose in the midst of the third session and walked out when it was agreed by the rest that the American note of protest to the Persian Government was not to be read or discussed. At this last meeting, the protocol of the two preceding meetings was drawn up, a copy of which the Russians attempted to obtain from the Dean, the Turkish Ambassador, who flatly refused to accede to their demand.

I have already pointed out to the Department, in my telegram No. 7 of July 28, that the Russian Delegation in Teheran has shown a curious interest in what they stated to have been Major Imbrie’s “anti-Bolshevist record” in Russia.

RELIGIOUS BACKGROUND

In the larger analysis, it may safely be said that the recrudescence of clerical power in Persia in the last two years has supplied the background and, in large part, the motivation for the tragedy which has just occurred. It is worth noting that never since the Persian Revolution of 1906, when the clergy was terrified into immobility by the public execution at the hands of the Revolutionaries of their Chief Mujtahed, Sheik Fazlullah, have the clergy been in possession of such dangerous power as is theirs today. So complete was their eclipse, that by 1918 it was possible to disregard their constitutional and religious right to interpret and execute the laws of the land in accordance with the Koran when a new Penal Code, based on the “Code of Napoleon”, was drafted and put into temporary execution pending its consideration and acceptance by the Mejliss. To anyone with even a slight knowledge of the corruption of the Persian Law Courts, this was an amazing act of progress.

It was not until the late summer of 1922, when the struggle between Reza Khan, then Minister of War, and the then Prime Minister, Ghavam-os-Saltaneh, had reached a critical stage, that the latter turned to the Mull ahs and enlisted their support in an attempt to break the menacing power of the War Minister. Be it said to Reza Khan’s credit, that although he is an uneducated man and has evinced a lamentable moral weakness in all the crises of his career, he is (fortunately for Persia) religiously tolerant and enlightened, and has freely made use in the Army and the Government of the intelligent services of the Bahá’ís, who may well be considered the only hope of Islam.

On the occasion above mentioned, Ghavam-os-Saltaneh, in order to reinforce his political position, then insecure, encouraged the Mullahs to make their notorious “Twelve Demands”, among which was the abolition of the Penal Code of 1918, obviously necessitating a return to the a rchaic religious courts. A second demand was the establishment of the Mullah’s Committee of Veto in the Mejliss, which is unfortunately provided for in Article 2 of the Supplement to the Constitution, but which has remained until the present time a dead letter.

To a close observer of Persian affairs it is beyond question that, had Reza Khan succeeded in establishing the Republic in March of this year, it would have been the death knell to the power of the clergy, which the latter realized only too well. I furthermore know personally that it was his firm determination to have proceeded, immediately upon the establishment of the Republic, with a revision of the Constitution which would have separated church from state and secularized the law.

It is curious that, for the first time since the establishment of Bolshevism in Russia, Great Britain and the Russians joined hands cordially in support of the clergy last March, in order to break the power of the Prime Minister and annihilate the Republic. It was they who subsidized and demonstrated in the gardens of the Mejliss on the day before the Republic was to be declared, and it was the fatal moral weakness of the Prime Minister in handling this demonstration which demolished at a blow his prestige with the Persians as “the dreaded and infallible Reza”.

The clergy immediately rose to the occasion, and they, who had the day before been suppliants, now became dictators. They directed what steps the Prime Minister should take thenceforth, that he should proceed forthwith to Qum for consultation with the exiled Mesopotamian Mullahs, who ordered him to publish his famous decree forbidding further discussion of the Republic.

Since that time Reza Khan’s political enemies have taken advantage of the restored prestige of the clergy to raise the hue and cry of Bahá’ísm against him, the danger of which accusation in present-day densely ignorant Persia is by no means to be underestimated. To many observers on the spot, the Prime Minister’s patience under these trying circumstances has appeared incomprehensible, and he has often been criticized for not having met the issue squarely and either smashed his opposition or gone down in defeat.

The reason for his inaction is unquestionably the fact that he has realized that any successful demonstrations against him at the present time may compromise his “American program”, which contains, of course, the passage of the oil bill. He has realized, furthermore, that it was a mistake to have proceeded with his republic last March before his program was completed, and it is now definitely known that he is determined at all costs to keep the Mejliss open until the oil bill has passed, after which there is every reason to believe the Deputies wi ll be immediately dismissed and Reza Khan will assume dictatorial powers in the country. The realization of this situation on the part of the clerical opposition has incited them more than anything else to oppose the passage of the bill.

From a knowledge of Persian affairs, it is impossible to believe that the so-called miracle, which occurred some two weeks previous to Imbrie’s death, was a spontaneous occurrence.

It had the earmarks from the beginning of an artificially inspired movement, of which the organized powers of evil were quick to take advantage in order to create disorder for the Government. It is well-known that large sums of money were paid to a committee organized at the Sakheh Khaneh, to which even peasants made contributions in sheep and grain. The sums collected are variously estimated from five to twenty thousand tomans. It is generally believed that the big grandees of Persia generously donated, among them being Vossough-ed-Dowleh, the notorious Anglophile Prime Minister of the Anglo- Persian Agreement, Ghavam-os-Saltaneh, his brother, now in exile, and Farman Farma, the most notorious of British agents. Reza Khan found himself faced with a situation before which he was powerless. The fanaticism of the crowd was so incited by the continuous preaching of the Mullahs that any act on his part would have been interpreted as treason to Islam and prima facie evidence that he was a Bahá’í; hence his unfortunate orders to the military and the police not to intervene under any circumstances in religious demonstrations and under no circumstances to fire.

It is clear that such a spot as the Sakheh Khaneh would be chosen by both foreign and domestic troublemakers as an advantageous station for their spies and agents, and the secret of this affair will never be fully revealed until the true character and affiliations of the hangers-on at the Sakheh Khaneh have been ascertained. It is obvious that the man in the crowd at the Sakheh Khaneh who had the presence of mind to spring to his feet the moment he saw Imbrie and cry, “That is a Bahá’í! He has poisoned the water of our Sakheh Khaneh and killed Musselmen women and children!” is of more than passing importance to the prosecution. It has been stated that this man is the same Seyed Hossein who stormed the operation room with the Cossacks; but I have not received confirmation of this.

Viewing the tragedy, in its larger issue, one is led to the inevitable conclusion that, unless Reza Khan is able and willing to purge the military of its criminal lawlessness, and, unless the malign power of the clergy can be broken forever in the land, there is every reason to believe that the killing of Imbrie is but a foretaste of more terrible events to come.

I have the honor to be, Sir, Your obedient servant,

(signed) W. Smith Murray Second Secretary of Legation In charge of Consulate

IMBRIE, ROBERT W

MAJOR FRENCH ARMY WW

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 07/18/1924

- DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

- BURIED AT: SECTION D SITE LOT 2903

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard