May 28, 2001

VISTA — It’s been a long time since Bob Maulding left his home and family on their avocado ranch here.

So long ago that everyone is gone.

His older brother went down with a submarine in 1943.

His mother and father, who lost two sons in World War II, have been dead for 20 years.

His younger brother died in 1988.

Though Maulding has no close family left to remember him, his friends refused to forget that he and other Marines were cut down and left behind on a lonely Pacific atoll 59 years ago.

His boyhood pal, Harry Reynolds, didn’t forget. Nor did John McCarthy, whose sister was Maulding’s fiancée.

Maulding’s fellow Marine Raiders, elite World War II commandos, reminded people constantly. And once engaged, the experts at the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii had a hard time forgetting, too.

Because those people wouldn’t forget, Private. Robert Maulding and his comrades will be coming home soon as honored war dead.

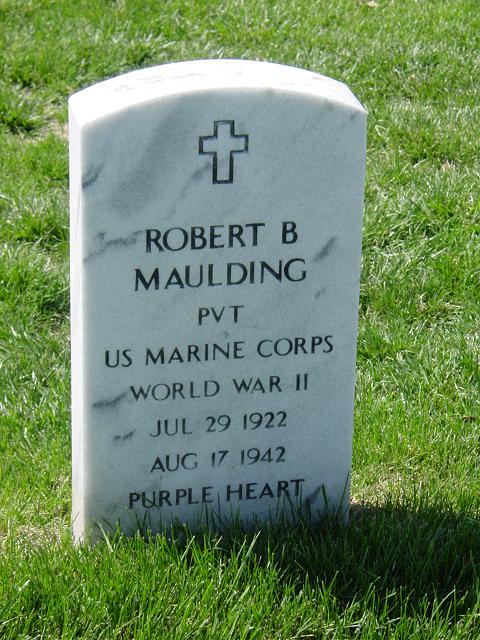

On August 17, 2001, exactly 59 years after they were killed in a short but furious firefight with Japanese soldiers on Makin Atoll, Maulding and most of his comrades will be laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery.

President Bush is invited.

Almost brothers

Harry Reynolds was more than Bob Maulding’s friend. He was the closest thing to a brother a guy could be, without actually being one.

So close that when the Maulding family moved to Beverly Hills in 1939, Reynolds moved with them. He wasn’t going to stay at Hollywood High while Bob and his older brother, George, were living it up at Beverly Hills High.

No way.

The Maulding boys and Reynolds had a great time, until the vice principal caught on and banished Reynolds back to Hollywood High.

But that wasn’t the end of the world.

Bob took up the trumpet at the insistence of his dad, a Hollywood musician. He and George traveled with a band to the Golden Gate International Exposition, and Bob led a high school dance band.

The Mauldings played on the Beverly Hills High football team, which won a championship in 1940, right before Bob graduated. Bob was named all-league end.

Life was nearly perfect, except that their younger brother, Jimmy, suffered from crippling arthritis.

fter their dad bought an avocado grove on Fruitland Drive in Vista, the family summered there, and in 1940 Bob got a job at San Luis Rey Downs in Bonsall. Reynolds followed. They worked there three months, and loved it.

“He and I had discussions about going into the horse business,” Reynolds, now 79, recalled from his home in Las Vegas. They went to war instead.

Staying together

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, nothing was the same for George and Bob Maulding, for Harry Reynolds, for anyone in the United States.

George joined the Navy, Reynolds the Marines.

Bob, at 17, was too young to enlist, so he altered his birth certificate and signed up with the Marines.

After boot camp, Bob proposed to Marie Ann McCarthy, who sang in his band. She was 16. The night they became engaged, they had their picture taken at the Hollywood Palladium.

John McCarthy, Marie Ann’s brother, was 11.

“When he came home on his last leave from San Diego, he gave me the Marine Corps emblem off his hat,” McCarthy said, even though Maulding risked not being readmitted to the base.

“I still have it. It’s a cherished memento,” said McCarthy, who now lives in Irvine.

Maulding and Reynolds trained separately at Camp Elliot in San Diego.

Reynolds heard about a new outfit, the 2nd Marine Raiders Battalion.

The commanding officer was Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson, whose unit slogan — “Gung-ho,” Chinese for “work together” — would become an Americanism.

Major James Roosevelt, the president’s son, was executive officer. Roosevelt promised prospective Raiders they would be among the first to engage the Japanese.

That was what Reynolds wanted. Maulding signed up, too. They were together again.

Firefight in the palms

In summer 1942, the United States was bent on stopping Japanese momentum in the Pacific. Japan had extended its realm as far east as the Gilbert Islands, on the equator, about 2,500 miles southwest of Hawaii.

The U.S. armed forces planned a quick-strike raid on the Gilberts — known today as Kiribati — to divert Japanese attention from the pivotal battle taking shape at Guadalcanal, on Australia’s doorstep.

Two Marine Raider companies, including Maulding’s, boarded submarines in Hawaii and set off for Butaritari Island, part of Makin Atoll in the Gilberts, to destroy a Japanese seaplane base there. It didn’t come off as planned.

Buck Stidham of El Cajon, a sergeant in Maulding’s company, described the Makin Raid.

It was about 3 a.m. August 17, he recalled, when the subs Nautilus and Argonaut surfaced off Butaritari in a heavy rain.

“The seas were running a little high,” said Stidham, 82. “Kind of a bad situation.”

The 220 Marines were to use 22 rubber boats for a dash to the beach. Only two of the outboard motors would start.

The Marines bounced around in the surf, trying to get the engines to start, then drifted ashore. Well-rehearsed plans gave way to improvisation.

A Marine accidentally fired his weapon, eliminating any hope of surprise.

The Raiders lined up across the narrow strip of land and started walking. Soon they saw the Japanese coming, and the two sides fired at each other over a distance of 30 yards.

“It was just two skirmish lines across the island, from palm tree to palm tree, in a big military version of the OK Corral,” Stidham recalled.

Nearly all the casualties occurred in those first minutes.

Sergeant Clyde Thomason died trying to direct his platoon’s fire, and would become the first enlisted Marine in World War II to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

Not far away, Pvt. Robert Maulding lay bleeding on the sand. He had just turned 18.

That morning the Marines killed nearly the entire enemy garrison, although they didn’t know it.

Two seaplanes tried to land, but Stidham and other gunners destroyed both. Two enemy boats appeared in the lagoon, but the Raiders guided fire from the submarines’ deck guns to sink them.

Japanese planes bombing and strafing the island hit no one.

Carlson, believing the Japanese were massing to attack, consulted his officers and ordered a withdrawal.

“That’s when the trouble began,” Stidham said.

The Marines tried to paddle out through the breakers, but some boats capsized. About 60 men made their way to the submarines, but most were thrown back to shore by the surf, their weapons lost.

The next morning, Stidham and Roosevelt and some Raiders forced their boats through the surf to a sub.

Carlson’s command, having determined that the Japanese were nearly wiped out, completed the mission, destroying the base and supplies. They got away by tying their boats together in the lagoon and paddling out of the inlet.

They had no choice but to leave their fallen comrades. Carlson gave an islander $50 to bury the dead.

Back aboard the submarines, the two companies were jumbled, preventing a full count until they reached Hawaii.

Reynolds was waiting for Maulding at Pearl Harbor, but he couldn’t find him getting off the sub. Maulding was one of 18 confirmed dead. Twelve others were missing and believed dead. Carlson counted 83 enemy soldiers killed.

Keeping faith

The Makin Raiders were celebrated as heroes, for while the raid may not have been strategically significant, it lifted the spirits of the nation.

After the war, the Marines learned that nine of the 12 missing Raiders were captured and taken to Kwajalein, where they were beheaded. Their remains have never been found. A Japanese officer was executed for the war crime.

One of Reynolds’ last conversations with Maulding was on a destroyer, the night before they reached Hawaii.

“We were up on deck, just talking, and suddenly he said to me: ‘Harry, if anything happens to me, I want you to do me a favor. Would you please tell my mom and dad how much I appreciated how they raised me and all the good things they did for me,

and tell Marie Ann how much I love her?’ ”

He then asked Reynolds if he wanted him to pass anything along.

“I said, ‘Hell, I gotta take your message back,’ ” Reynolds said.

The Army seized Makin Atoll from the Japanese in 1943, but apparently no attempt was made to find the Raiders’ grave.

Five years later the Defense Department searched, but came up empty.

Fifty years later, under pressure from surviving Raiders, the Defense Department told the Army’s identification lab in Hawaii to find the Makin Raiders and bring them home.

A lab team searched Butaritari in 1998, but had no luck. Then in December 1999, floods canceled a search team’s scheduled trip to Vietnam, so the members detoured to Butaritari.

The team surveyed the island with a resident who had helped bury the bodies 57 years earlier.

“On the fourth day he was able to orient himself and pointed to a place where he believed they were buried,” said Johnie Webb, the laboratory’s deputy director.

The team trenched around the site and uncovered a skull.

The search then exposed old explosives, more human remains, bits of buckles, snaps and other hardware. Some Raiders had been buried in full uniform, and their helmets had fused to their skulls.

After 10 days of digging, the team reclaimed 19 Raiders from a mass grave. It is among the lab’s most significant finds.

fter unearthing the bodies, the team still had to sort and identify them. To be positive, the Army needed a maternal relative to make a DNA match.

In Maulding’s case, that was a tough assignment.

Bob Maves, a casualty data analyst with the lab, said Maulding’s maternal relatives had divorced and remarried, making them hard to find. A cousin in Botswana, Africa, was difficult to reach.

After much detective work, Maves tracked down the ex-husbands of Maulding’s aunts. They put him in touch with their children, who directed him to their mothers. DNA from blood samples provided by the women made it possible to identify their nephew’s remains last October. Private Robert Maulding was on his way home.

Brothers at last

Al and Daphne Maulding had sent two sons off to war, but neither came back. Bob died in the sand on Makin Atoll, and George disappeared with his submarine, the much-decorated Wahoo, off Japan.

It was customary during the war for families to display service flags, with stars representing sons or daughters in the armed forces. A gold star stood for a service member who had died, a blue star for one still alive.

“When I came home from overseas, the first place I went was to see them,” Reynolds recalled, “and when I got to the front of the house there was a service flag hanging in the window, with two gold stars and a blue one for me.

“I choke up and a tear comes to my eye right now when I think of that. I knew I belonged to the Maulding family when I saw that.”

The cousin in Botswana designated Reynolds as the “nearest relative” for the purpose of deciding what to do with Maulding’s remains. So Reynolds, who had always regarded Maulding as his brother, now officially is.

He will stand for Maulding, along with other family members, at Arlington.

Click Here For More Information

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard