Friday August 17, 2001:

WWII Marines Buried at Arlington

Playing “Onward! Christian Soldiers,” the Marine Band marched Friday along the twisting paths of Arlington National Cemetery to the open grave sites of 13 World War II Marines whose remains had lain nearly 60 years in a mass grave on a South Pacific battlefield.

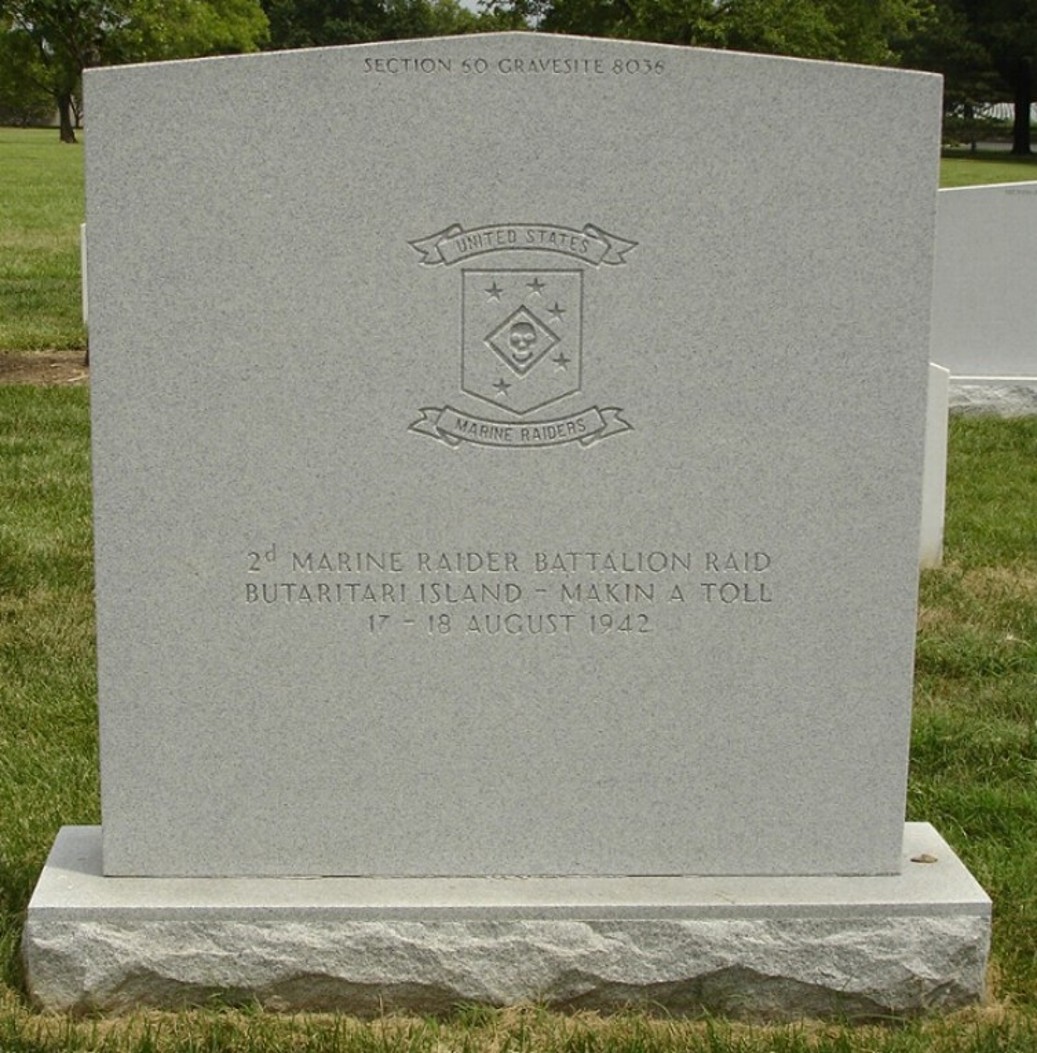

The full honors ceremony marked the homecoming of 2nd Raider Battalion Marines killed during a 1942 raid on Makin Atoll in the Gilbert Islands.

The battalion destroyed most of its target, a Japanese seaplane base. But, hurriedly departing under fire from hostile aircraft, they were unable to carry away their dead.

“Marines of today draw inspiration from the ‘Greatest Generation,”’ said General James L. Jones, Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps., at a service in Fort Myer Chapel. “We learn from their courage.”

Jones said the raid lifted American morale early in the war and demonstrated the nation was willing to take the fight to the enemy.

A horse-drawn caisson carried a casket containing remains that forensic experts were unable to identify

“These men were found in the same grave with their weapons and hand grenades,” said Bill Fisher, 75, a 2nd Battalion Raider.

A Marine honor guard lifted the flag-draped casket from the caisson and placed it among the coffins of individual Marines arrayed at the grave site in front of hundreds of family members.

“Taps” played by a lone bugler resonated through the silent afternoon. The flag from the casket with the remains of the unknowns was folded and given to Jones. Marines from the honor guard then handed each family the flag of its dead relative

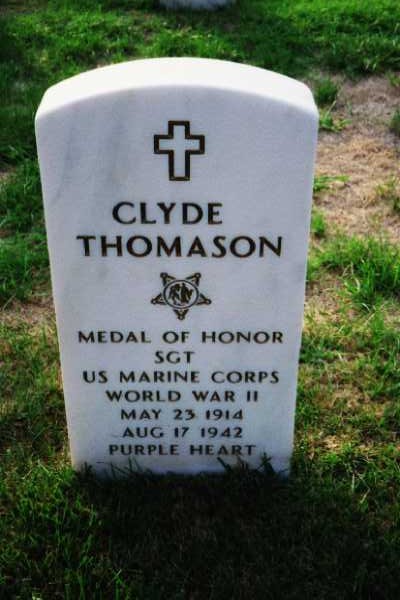

Hugh Thomason, of Bowling Green, Kentucky, took the flag of his half brother, Sergeant Clyde Thomason. “I had to sort of think of other things, otherwise I may not have been in a good emotional state to receive the flag,” said Thomason, 80, also a Marine who served in World War II and Korea. “It is representative of the esteem him and the other men are held in by the Marine Corps and other Americans.”

Thomason, who said his half brother was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, said, “It was very satisfying to bring the return of the remains to a close.”

The ceremony ended with a 21-gun salute.

The Defense Department made an unsuccessful attempt to recover remains on Makin in 1949. The search was renewed in 1998 by relatives of the dead and other World War II veterans. The break came when searchers found an elderly island resident who had helped bury the bodies as a young boy.

The 19 bodies were recovered two years ago and identified by the Army’s Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii. Six were returned to relatives who opted for private burials.

Investigators said they will begin searching next year for the remains of additional missing Marines who, military officials believe, were captured and executed by the Japanese on Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands.

From a news report: Friday August 17, 2001

WWII Marines Buried at Arlington

Thirteen World War II Marines whose remains were discovered on a South Pacific island nearly 60 years after they fell in battle were buried under gray skies Friday at Arlington National Cemetery.

The sun broke through the clouds just after a Marine bugler finished playing “Taps” and the chaplain of the United States Marine Raider Association led a prayer with family members and others attending the service.

“Today really signifies how the Marine Corps takes care of their own,” said Captain Joe Kloppel at the end of the service. “This ceremony put a finalization on the sacrifice that the Marines made for their country 59 years ago.”

It was a final homecoming for the Marines killed during a 1942 raid on the Japanese-held Makin Atoll in the Gilbert Islands.

An unsuccessful attempt to recover the bodies of 19 fallen Marines on Makin, now known as Butaritari, was made in 1949. The search was renewed in 1998 by relatives of men from the 2nd Raider Battalion and other World War II veterans.

The bodies, left on the small coral reef island after the two-day raid, were recovered and identified two years ago when searchers found an island resident who had helped bury the bodies as a young boy.

Six bodies were returned to families for burial. The remaining 13 Marines were flown Thursday from Hawaii to Andrews Air Force Base, where they were met by relatives and U.S. Marine Raider Association members.

Marines carried the flag-draped caskets to hearses bound for Arlington.

“They’re finally home, which is where I want to be when die,” said 81-year-old Captain Joe Griffith, the battalion’s only living officer. “They were good men and volunteers who did something over and above the call of duty by attempting to further the progress of engagement.”

Vernon Castle is one of the Raiders who will be buried on the 59th anniversary of the Battle of Makin, which was featured in the 1943 film “Gung Ho” starring Randolph Scott, Noah Beery Jr. and Robert Mitchum.

Castle’s sister, Vivian Yoder, traveled with her husband in a motor home from Hemet, California, to say goodbye.

“It will really provide closure after all of these years,” said Yoder, 78. “But there is something about military funerals that is always hard to take.”

Mary Baldwin of Spokane, Washington, said her husband, Robert, who died in December, served with the men. “Marines always take care of their own,” she said. “It is extremely important for the men to be brought home and honored.”

Among the 13 was Sergeant Clyde Thomason, posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor during the war.

Marine Raiders From World War II

Arrive At Andrews Air Force Base

16 August 2001

Wednesday August 15, 2001

Remains of WWII Marines Headed Home

Remains of WWII Marines to Be Buried

Thursday, August 16, 2001; 6:48 p.m. EDT

WASHINGTON –– The remains of 13 Marines killed on a South Pacific island in World War II will be buried Friday at Arlington National Cemetery.

The men were among 19 Marines from the 2nd Raider Battalion who were killed during a raid August 17, 1942, raid on the Japanese-held Makin Atoll, now known as Butaritari, in the Gilbert islands.

“They’re finally home, which is where I want to be when I die,” said 81-year-old Capt. Joe Griffith, the battalion’s only living officer. “They were good men and volunteers who did something over and above the call of duty by attempting to further the progress of engagement.”

The remains were flown Thursday from Hawaii to Andrews Air Force Base, where they were met by relatives and U.S. Marine Raider Association members. Marines carried the flag-draped caskets to hearses, which carried the men to Arlington.

Vernon Castle is one of the Raiders who will be buried on the 59th anniversary of the Battle of Makin. Castle’s sister, Vivian Yoder, traveled with her husband in a motor home from Hemet, Calif., to say goodbye.

“It will really provide closure after all of these years,” said Yoder, 78. “But there is something about military funerals that is always hard to take.”

Harold Williams, a Marine from Hialeah, Florida, said that while the war was still raging, he had to dig up the remains of men who died.

“They were buried without bags or boxes,” said Williams, 75, of Hialeah, Florida, who fought in the battle. “Being brought to Arlington National Cemetery is quite an honor compared to that.”

An unsuccessful attempt to recover remains on Makin was made in 1949. The search was renewed in 1998 by relatives of the dead and other World War II veterans; the break came when searchers found an island resident who had helped bury the bodies as a young boy.

The 19 bodies were recovered and identified two years ago. The other six remains were previously returned to families for burial.

Investigators said they will begin searching next year for the remains of an additional nine of 11 missing Marines who military officials believe were executed on Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands after being captured by the Japanese.

HICKAM AIR FORCE BASE, Hawaii (AP) – The remains of 13 Marines killed on a South Pacific atoll during World War II received a solemn send-off Wednesday en route to their final resting place.

A lone bagpiper played “Amazing Grace” as he strolled past the 13 flag-draped caskets. Marine pall bearers then loaded them into a KC-130 Marine Corps airplane for transport to Arlington National Cemetery, where they will be buried Friday.

“There is no statute of limitations on honor,” said Senator Daniel K. Inouye, D-Hawaii. “It is never too late to do what is right.”

The 13 were among 19 Marines from the 2nd Raider Battalion who were killed during an August 17, 1942, raid on the Japanese-held Makin Atoll, now known as Butaritari, in the Gilbert Islands.

Their bodies, left on the small coral reef island after the two-day raid, were buried together by local residents.

An unsuccessful attempt to recover remains on Makin was made in 1949. The search was renewed in 1998 by relatives of the dead and other World War II veterans; the break came when searchers found an island resident who had helped bury the bodies as a young boy.

The 19 bodies were recovered and identified two years ago. The other six remains were previously returned to families for burial.

Among the 13 was Sergeant Clyde Thomason, who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honorduring the war. His half-brother, Hugh Thomason, 80, of Bowling Green, Kwntucky will be among more than 40 of the late sergeant’s extended family who will be at Friday’s service.

“During all of 50 years, I never expected that they would ever be found,” said Thomason, a retired Colonel in the Marine Reserves. “Finally, it was all brought about.”

Investigators said they will begin searching next year for the remains of an additional nine of 11 missing Marines who military officials believe were executed on Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands after being captured by the Japanese.

PRESS ADVISORY from the United States Department of Defense

No. 157-P PRESS ADVISORY

August 14, 2001

The commandant of the Marine Corps, Gen. James L. Jones, will speak at a memorial service for Marines of the 2nd Raider Battalion who were killed during a raid on Butaritari Island in 1942. The service and subsequent burial will take place at Arlington National Cemetery on Friday, Aug. 17 at 11 a.m. EDT.

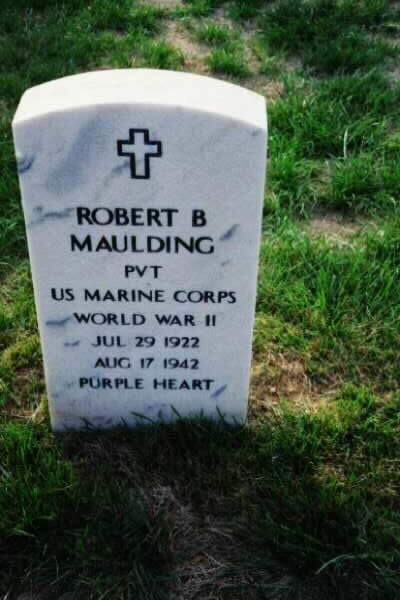

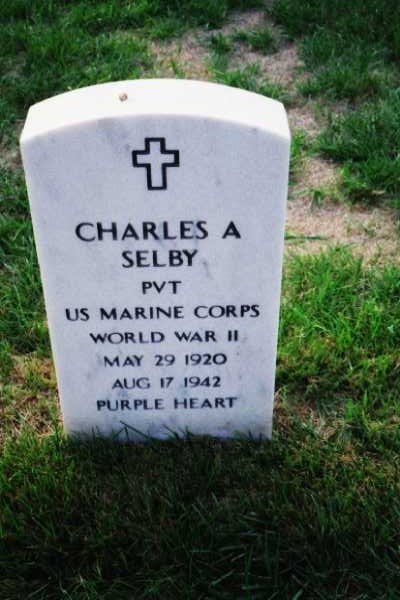

The remains are those of Captain Gerald P. Holtom, Palo Alto, California; Sergeant Clyde Thomason Atlanta, Georgia; FM1 Vernon L.Castle, Stillwater, Oklahoma; Corporal Daniel A. Gaston, Galveston, Texas;Corporal Edward Maciejewski, Chicago, Illinois; Corporal Robert B. Pearson, Lafayette, California; Private First Class William A. Gallagher, Wyandotte, Michigan; Private First Class Kenneth M. Montgomery, Eden, Wisconsin; Private First Class JohnE. Vandenberg, Kenosha, Wisconsin; Private Carlyle O. Larson, Glenwood, Minnesota; Private. Robert B. Maulding, Vista, California; Private Franklin M. Nodland, Marshalltown, Iowa; and Private Charles A. Selby, Ontonagon, Michigan.

The families of six other Marines killed during the raid elected to have private burials. A casket containing co-mingled remains will be interred during the ceremony in addition to the 13 individual caskets.

The 19 Marines were killed during a raid on Butaritari Island, in the Makin Atoll, August 17-18, 1942. They were members of the 2nd Raider Battalion, a Marine unit organized and trained to conduct commando and guerrilla-style attacks behind enemy lines. The unit was led by then-Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson and his econd-in-command, Major James Roosevelt, son of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Sergeant Clyde Thomason, whose remains will be among those interred Friday, was the first enlisted Marine to earn the Medal of Honor in World War II.

During the two-day battle, the Raiders killed an estimated 83 Japanese soldiers, but their attempts to leave the island were bedeviled by a high and crashing surf and they were unable to evacuate the bodies of their fallen comrades.

In November 1999, a recovery team from the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory, Hawaii (CILHI), uncovered a mass grave on Butaritari Island and excavated the remains. The remains were transported to CILHI where an exhaustive process led to the identification of the Marines and the subsequent notification of their families.

The remains will arrive at Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland, on Thursday at 9:30 a.m. An arrival ceremony will be conducted by Marines from Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C. and the President’s Own, United States Marine Band. For media access to the arrival at Andrews or the ceremony at Arlington, contact Marine Capt. Joseph Kloppel at (703) 614-4309.

May 28, 2001

Please note the story was written by Michael Burge and appeared in The San Diego Union-Tribune on May 28, 2001. It was an honor for me to meet the Marines who served in that raid, and to tell the story of bringing their comrades’ remains back home. My interview with the late Buck Stidham stays with me to this day. I have no objection to its appearance, but I’d appreciate it if you credit me and my newspaper, which owns the copyright.

Thank you.

Michael Burge, Staff Writer, The San Diego Union-Tribune

VISTA — It’s been a long time since Bob Maulding left his home and family on their avocado ranch here.

So long ago that everyone is gone.

His older brother went down with a submarine in 1943.

His mother and father, who lost two sons in World War II, have been dead for 20 years.

His younger brother died in 1988.

Though Maulding has no close family left to remember him, his friends refused to forget that he and other Marines were cut down and left behind on a lonely Pacific atoll 59 years ago.

His boyhood pal, Harry Reynolds, didn’t forget. Nor did John McCarthy, whose sister was Maulding’s fiancée.

Maulding’s fellow Marine Raiders, elite World War II commandos, reminded people constantly. And once engaged, the experts at the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii had a hard time forgetting, too.

Because those people wouldn’t forget, Private. Robert Maulding and his comrades will be coming home soon as honored war dead.

On August 17, 2001, exactly 59 years after they were killed in a short but furious firefight with Japanese soldiers on Makin Atoll, Maulding and most of his comrades will be laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery.

President Bush is invited.

Almost brothers

Harry Reynolds was more than Bob Maulding’s friend. He was the closest thing to a brother a guy could be, without actually being one.

So close that when the Maulding family moved to Beverly Hills in 1939, Reynolds moved with them. He wasn’t going to stay at Hollywood High while Bob and his older brother, George, were living it up at Beverly Hills High.

No way.

The Maulding boys and Reynolds had a great time, until the vice principal caught on and banished Reynolds back to Hollywood High.

But that wasn’t the end of the world.

Bob took up the trumpet at the insistence of his dad, a Hollywood musician. He and George traveled with a band to the Golden Gate International Exposition, and Bob led a high school dance band.

The Mauldings played on the Beverly Hills High football team, which won a championship in 1940, right before Bob graduated. Bob was named all-league end.

Life was nearly perfect, except that their younger brother, Jimmy, suffered from crippling arthritis.

fter their dad bought an avocado grove on Fruitland Drive in Vista, the family summered there, and in 1940 Bob got a job at San Luis Rey Downs in Bonsall. Reynolds followed. They worked there three months, and loved it.

“He and I had discussions about going into the horse business,” Reynolds, now 79, recalled from his home in Las Vegas. They went to war instead.

Staying together

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, nothing was the same for George and Bob Maulding, for Harry Reynolds, for anyone in the United States.

George joined the Navy, Reynolds the Marines.

Bob, at 17, was too young to enlist, so he altered his birth certificate and signed up with the Marines.

After boot camp, Bob proposed to Marie Ann McCarthy, who sang in his band. She was 16. The night they became engaged, they had their picture taken at the Hollywood Palladium.

John McCarthy, Marie Ann’s brother, was 11.

“When he came home on his last leave from San Diego, he gave me the Marine Corps emblem off his hat,” McCarthy said, even though Maulding risked not being readmitted to the base.

“I still have it. It’s a cherished memento,” said McCarthy, who now lives in Irvine.

Maulding and Reynolds trained separately at Camp Elliot in San Diego.

Reynolds heard about a new outfit, the 2nd Marine Raiders Battalion.

The commanding officer was Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson, whose unit slogan — “Gung-ho,” Chinese for “work together” — would become an Americanism.

Major James Roosevelt, the president’s son, was executive officer. Roosevelt promised prospective Raiders they would be among the first to engage the Japanese.

That was what Reynolds wanted. Maulding signed up, too. They were together again.

Firefight in the palms

In summer 1942, the United States was bent on stopping Japanese momentum in the Pacific. Japan had extended its realm as far east as the Gilbert Islands, on the equator, about 2,500 miles southwest of Hawaii.

The U.S. armed forces planned a quick-strike raid on the Gilberts — known today as Kiribati — to divert Japanese attention from the pivotal battle taking shape at Guadalcanal, on Australia’s doorstep.

Two Marine Raider companies, including Maulding’s, boarded submarines in Hawaii and set off for Butaritari Island, part of Makin Atoll in the Gilberts, to destroy a Japanese seaplane base there. It didn’t come off as planned.

Buck Stidham of El Cajon, a sergeant in Maulding’s company, described the Makin Raid.

It was about 3 a.m. August 17, he recalled, when the subs Nautilus and Argonaut surfaced off Butaritari in a heavy rain.

“The seas were running a little high,” said Stidham, 82. “Kind of a bad situation.”

The 220 Marines were to use 22 rubber boats for a dash to the beach. Only two of the outboard motors would start.

The Marines bounced around in the surf, trying to get the engines to start, then drifted ashore. Well-rehearsed plans gave way to improvisation.

A Marine accidentally fired his weapon, eliminating any hope of surprise.

The Raiders lined up across the narrow strip of land and started walking. Soon they saw the Japanese coming, and the two sides fired at each other over a distance of 30 yards.

“It was just two skirmish lines across the island, from palm tree to palm tree, in a big military version of the OK Corral,” Stidham recalled.

Nearly all the casualties occurred in those first minutes.

Sergeant Clyde Thomason died trying to direct his platoon’s fire, and would become the first enlisted Marine in World War II to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

Not far away, Pvt. Robert Maulding lay bleeding on the sand. He had just turned 18.

That morning the Marines killed nearly the entire enemy garrison, although they didn’t know it.

Two seaplanes tried to land, but Stidham and other gunners destroyed both. Two enemy boats appeared in the lagoon, but the Raiders guided fire from the submarines’ deck guns to sink them.

Japanese planes bombing and strafing the island hit no one.

Carlson, believing the Japanese were massing to attack, consulted his officers and ordered a withdrawal.

“That’s when the trouble began,” Stidham said.

The Marines tried to paddle out through the breakers, but some boats capsized. About 60 men made their way to the submarines, but most were thrown back to shore by the surf, their weapons lost.

The next morning, Stidham and Roosevelt and some Raiders forced their boats through the surf to a sub.

Carlson’s command, having determined that the Japanese were nearly wiped out, completed the mission, destroying the base and supplies. They got away by tying their boats together in the lagoon and paddling out of the inlet.

They had no choice but to leave their fallen comrades. Carlson gave an islander $50 to bury the dead.

Back aboard the submarines, the two companies were jumbled, preventing a full count until they reached Hawaii.

Reynolds was waiting for Maulding at Pearl Harbor, but he couldn’t find him getting off the sub. Maulding was one of 18 confirmed dead. Twelve others were missing and believed dead. Carlson counted 83 enemy soldiers killed.

Keeping faith

The Makin Raiders were celebrated as heroes, for while the raid may not have been strategically significant, it lifted the spirits of the nation.

After the war, the Marines learned that nine of the 12 missing Raiders were captured and taken to Kwajalein, where they were beheaded. Their remains have never been found. A Japanese officer was executed for the war crime.

One of Reynolds’ last conversations with Maulding was on a destroyer, the night before they reached Hawaii.

“We were up on deck, just talking, and suddenly he said to me: ‘Harry, if anything happens to me, I want you to do me a favor. Would you please tell my mom and dad how much I appreciated how they raised me and all the good things they did for me,

and tell Marie Ann how much I love her?’ “

He then asked Reynolds if he wanted him to pass anything along.

“I said, ‘Hell, I gotta take your message back,’ ” Reynolds said.

The Army seized Makin Atoll from the Japanese in 1943, but apparently no attempt was made to find the Raiders’ grave.

Five years later the Defense Department searched, but came up empty.

Fifty years later, under pressure from surviving Raiders, the Defense Department told the Army’s identification lab in Hawaii to find the Makin Raiders and bring them home.

A lab team searched Butaritari in 1998, but had no luck. Then in December 1999, floods canceled a search team’s scheduled trip to Vietnam, so the members detoured to Butaritari.

The team surveyed the island with a resident who had helped bury the bodies 57 years earlier.

“On the fourth day he was able to orient himself and pointed to a place where he believed they were buried,” said Johnie Webb, the laboratory’s deputy director.

The team trenched around the site and uncovered a skull.

The search then exposed old explosives, more human remains, bits of buckles, snaps and other hardware. Some Raiders had been buried in full uniform, and their helmets had fused to their skulls.

After 10 days of digging, the team reclaimed 19 Raiders from a mass grave. It is among the lab’s most significant finds.

fter unearthing the bodies, the team still had to sort and identify them. To be positive, the Army needed a maternal relative to make a DNA match.

In Maulding’s case, that was a tough assignment.

Bob Maves, a casualty data analyst with the lab, said Maulding’s maternal relatives had divorced and remarried, making them hard to find. A cousin in Botswana, Africa, was difficult to reach.

After much detective work, Maves tracked down the ex-husbands of Maulding’s aunts. They put him in touch with their children, who directed him to their mothers. DNA from blood samples provided by the women made it possible to identify their nephew’s remains last October. Private Robert Maulding was on his way home.

Brothers at last

Al and Daphne Maulding had sent two sons off to war, but neither came back. Bob died in the sand on Makin Atoll, and George disappeared with his submarine, the much-decorated Wahoo, off Japan.

It was customary during the war for families to display service flags, with stars representing sons or daughters in the armed forces. A gold star stood for a service member who had died, a blue star for one still alive.

“When I came home from overseas, the first place I went was to see them,” Reynolds recalled, “and when I got to the front of the house there was a service flag hanging in the window, with two gold stars and a blue one for me.

“I choke up and a tear comes to my eye right now when I think of that. I knew I belonged to the Maulding family when I saw that.”

The cousin in Botswana designated Reynolds as the “nearest relative” for the purpose of deciding what to do with Maulding’s remains. So Reynolds, who had always regarded Maulding as his brother, now officially is.

He will stand for Maulding, along with other family members, at Arlington.

Honorable Burial at Last for Makin Atoll Heroes

Marines’ remains left behind in ’42 are found

December 26, 2000

Three of the men were from Northern California, and all of them, the Marines say, were heroes.

The three were Captain Gerald Holtom, an intelligence officer who went to college in Berkeley and lived in Palo Alto, Corporal Robert Pearson, an infantryman from Lafayette, and Corporal I. B. Earles of the San Joaquin Valley town of Tulare.

The remains of Sergeant Clyde Thompson, of Atlanta, the first enlisted Marine to win the Medal of Honor, were among those recovered.

They were killed in a raid on the Japanese-held Makin atoll in the Gilbert Islands in the summer of 1942. It was a daring operation, conducted in great secrecy 2,000 miles behind enemy lines. The leader was the lean, leathery and tough as nails Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson. His right-hand man was Major James Roosevelt, son of the President of the United States.

The raid electrified the country: It was hailed as the first successful Allied ground attack against the Axis. The Raiders’ motto “Gung Ho!” — a Chinese expression meaning “work together” — became part of the American vocabulary. There was even a hit movie, with Randolph Scott playing Carlson.

Yet the Makin raid was a victory that never was, a muddled and confused affair in which the Americans nearly surrendered to a defeated enemy. The raid also alerted the Japanese enemy to American capabilities, and the Japanese took vigorous countermeasures with serious and bloody consequences.

“This thing was a real screwup, a mess,” said Ben Carson, a retired Forest Service officer who was a Private in the raid. Worse, the raiders left behind 19 of their dead comrades and nine living Marines.

“Marines never forget their dead. Marines never leave their dead,” said Jack Dornan of the Marine Raiderr Association, which is composed of veterans of the raiders, the elite of the elite corps.

.The nine Marines left behind were captured, taken to Kwajalein Island and beheaded.

“This thing has been haunting me and many others for years,” said Graydon Harn, who along with Carson led attempts to find the graves of the 19 dead Marines on Makin and have them returned to the United States.

BREAKTHROUGH TO UNCOVER REMAINS

It was a long and difficult battle. The Defense Department had searched for the bodies in 1948 but found nothing. Years later, Harn and Carson, backed by their comrades in the Marine Raiders Association, began pressuring the Pentagon, writing their representatives in Congress and using computers to broaden the scope of their work.

“I could not have done it without the help of Congresswoman Elizabeth Furse, ” Carson said. Furse, a Democrat from Oregon, represented the district near the Republican Carson’s home in Hillsboro, near Portland.

“I could not have done it without the computer,” said Harn, who got a computer as a gift from his family. He went to work sending e-mails all over the world, especially to the island of Butaritari, which is part of the Makin atoll, a tiny slice of the independent nation of Kiribati.

The Marine Raiders put pressure on the Pentagon’s POW/MIA office, which has been working on identifying military remains in Vietnam.

A forensic anthropologist and his team went to the island in 1998 and got a huge break when an 82-year-old islander named Bureimoa Tokarei came forward to say he had buried the men when he was a boy of 16 and knew the location.

The remains, including dogtags and bits of uniform, were removed later, taken to the armed services forensic lab in Hawaii, where, using DNA and dental records, 19 men were positively identified last month.

The memory of those Marines was strong on Makin; when a U.S. Marine honor guard went to the island last winter to move the remains to the United States, Bureimoa Tokarei, who does not speak English, came to attention and began to sing the Marine Corps anthem. “He sang it completely,” Harn said. “The whole thing. He knew more verses than I did.”

ELITE FIGHTING FORCE

The pull of tradition and valor was very much part of Carlson and his raiders. The Raiders were an elite unit specializing in guerrilla tactics. They existed only for two years; then they became part of Marine legend.

Carlson was the son of a preacher, a professional officer who had served in the Army in World War I, later joined the Marines as a private, became an officer, served in China and won the Navy Cross in Nicaragua in the 1930s.

He also made powerful friends: while assigned to the Presidential Security Detail at the “Little White House” in Warm Springs, Ga., he was noticed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Carlson went back to China and studied the guerrilla methods used by Mao Tse Tung and his communist army. He also took note of their “Gung Ho” spirit. Carlson wrote regular reports for the eyes of the president only.

When America entered the war, Roosevelt was being pressured by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to form a small, elite force along the lines of the British commandos. Carlson also was friendly with James Roosevelt, then a Marine reserve officer. He got the job, and two battalions of raiders — called “Carlson’s Raiders” by the troops — were formed. Carlson made the younger Roosevelt his executive officer.

Their first mission was a surprise raid on the obscure Makin Atoll. The purpose was to divert the Japanese from the real attack on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, capture documents and knock the Japanese off balance.

The Raiders, handpicked and led by Carlson himself, trained in amphibious war near Honolulu. But while Carlson was long on bravery and theory, he was short on detail.

SUB-PAR TRAINING

Carson remembers that though the men were to make the assault from submarines, they never trained on subs and had never even been on a sub before.

Nonetheless, in early August, they sailed from Pearl Harbor aboard two old submarines, the Nautilus and the Argonaut.

But when they got to Makin, huge seas were running. “It was just a hellacious storm,” he said, “The waves must have been 20 feet high.”

They had a terrible time launching the rubber boats. In fact, they had never launched boats from a submarine. Many of the boats were swamped. They lost a lot of equipment, a lot of ammunition.

The Marines — there were 13 officers and 208 enlisted men — got ashore before dawn when it was “as dark as the inside of a black cow,” Carson said. The idea was to surprise the sleeping Japanese garrison.

But one Marine accidentally fired his rifle, a sound that would wake the dead, and the Japanese boiled out of their barracks.

It was the Raiders’ first fight, and it was fierce. “I remember the heroism, ” Carson said. “We were seeing that for the first time. There was the heroism of those men.”

The Japanese were outnumbered, but the Raiders didn’t know that. The enemy made several terrifying Banzai charges, attacks that sent most soldiers running, but not the Marines.

The Japanese also employed snipers in the trees. It was a sniper who killed Capt. Holtom, the only officer to die. “He was buried near where he fell,” Carlson wrote the family later. “He died like a man and a true patriot.”

The battle for Makin was desperate and confusing. The Marines ran short of ammunition, and at one point, Carlson thought the Raiders had lost and wanted to surrender. The Marines sent a note to the enemy by a Japanese messenger, but in the confusion the messenger was shot and killed.

LAND OF CONFUSION

By the next morning, it turned out that the Japanese were all dead. The Marines had won. But they were dissorganized.

Some of them, without much direction, made their way back to the submarines.

It was a terrible mess. Even the outboard motors didn’t work, and neither did the radios. The men had to paddle out to sea, hoping to spot the submarines.

They hadn’t intended to hold the island anyway. But when they counted heads, four Marines were missing, left behind.

Five men volunteered to go back to try to find the missing men. “We were back in the safety of that boat,” Carson said, “and they went back for their buddies.”

But Japanese planes had been alerted and flew over Makin and dropped bombs. The submarines dived, and when they surfaced, there was no sign of any Marines.

The submarines couldn’t wait. The element of surprise was gone and they couldn’t stay in enemy waters. So they headed back for Pearl Harbor. They received a hero’s welcome, and Adm. Chester Nimitz himself was there to meet the Raiders. It was a famous victory.

DESERTED ON AN ISLAND

On Makin, the lost Marines held out for a while, but they were alone, thousands of miles from friendly forces. They surrendered, and were killed by their captors on Kwajalein.

The fate of those men still haunts the Marines. Old men now, but still proud. “There is one thing you learn in the Marine Corps,” said Harn, who is 78 and in poor health. “There are feelings that last all your life. We became like brothers. Like brothers.”

Sixteen of the men from Makin will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, including all that is mortal of Holtum, the intelligence officer from Palo Alto, and Pearson, the infantryman from Lafayette. Earles will be buried next to his

father and mother in Tulare.

There will be a ceremony at Arlington Aug. 19, the 59th anniversary of the day they died.

The remains of the nine Marines executed on Kwajalein have never been recovered. They are still there, like a memory that will not fade away.

In August 1945, the United States erupted in joyous celebration as Japan unconditionally surrendered and World War II came to a close. In the ensuing months, tens of thousands of American service members came home to a grateful nation and tearful reunions with their friends and families.

However, the loved ones of more than 78,000 service members did not experience such reunions. For them, World War II never really ended as their family members and friends were listed as missing in action.

In Nov. and Dec. 1999, the Army’s Central Identification Laboratory (CILHI), based at Hickam AFB, Hawaii, recovered the remains of 19 Marine Raiders who died during the August 1942 raid on Makin Atoll.

The recovery brought to a close a search that initially began in 1948 when a Graves Registration Team searched Makin Atoll for the bodies of the 18 Marines killed and 12 listed as missing from the raid but found nothing. Fifty years later, while en route to Hawaii from a search in Vietnam, a two-man survey team from CILHI was forced to divert to Makin due to heavy rains.

While there, the team interviewed island residents and set the stage for later search operations. An excavation in May 1999 turned up nothing, but in November 1999, researchers discovered a mass grave containing human remains, equipment, and dog tags belonging to some of the Raiders. Bureimoa Tokarei, who was 16 at the time of the raid, helped bury the Marines and led investigators to within meters of the burial site.

An exhaustive identification process conducted by CILHI, in conjunction with various other governmental agencies, led to the identification of 19 Marine Raiders that were listed as killed or missing nearly six decades earlier. They were identified as:

- Capt. Gerald P. Holtom, Palo Alto, Calif. *

- Sgt Clyde Thomason, Atlanta, Ga. *

- Field Musician 1st Class Vernon L. Castle, Stillwater, Okla. *

- Cpl I.B. Earles, Tulare, Calif.

- Cpl Daniel A. Gaston, Galveston, Tex. *

- Cpl Harris J. Johnson, Little Rock, Iowa *

- Cpl Kenneth K. Kunkle, Mountain Home, Ark.

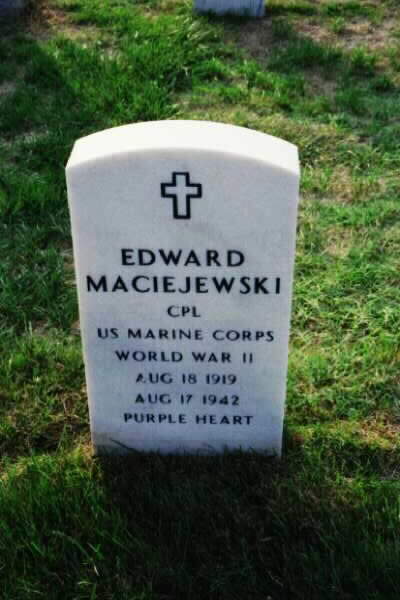

- Cpl Edward Maciejewski, Chicago, Ill. *

- Cpl Robert B. Pearson, Lafayette, Calif. *

- Cpl Mason O. Yarbrough, Sikeston, Mo.

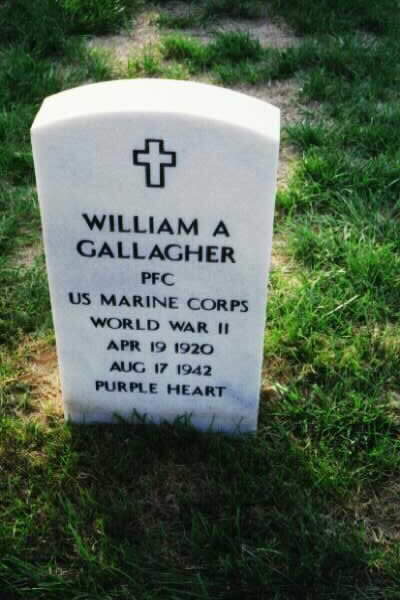

- Pfc William A. Gallagher, Wyandotte, Mich. *

- Pfc Ashley W. Hicks, Waterford, Calif.

- Pfc Kenneth M. Montgomery, Eden, Wis. *

- Pfc Norman W. Mortensen, Camp Douglas, Wis.

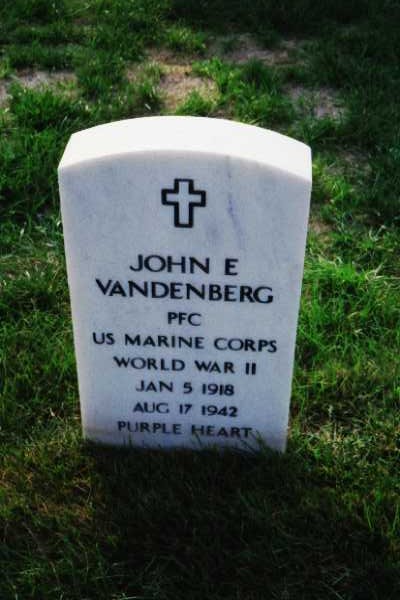

- Pfc John E. Vandenberg, Kenosha, Wis. *

- Pvt Carlyle O. Larson, Glenwood, Minn. *

- Pvt Robert B. Maulding, Vista, Calif. *

- Pvt Franklin M. Nodland, Marshalltown, Iowa *

- Pvt. Charles A. Selby, Ontonagon, Mich. *

* Buried In Arlington National Cemetery

Of the 30 Marines who did not return from the raid on Makin Atoll, 11 have yet to be found. Nine of the Marines, who were inadvertently left behind after the raid, were captured by the Japanese and later taken to Kwajalein Island, where they were executed. The location of the other two Marines remains a mystery, and search operations for those yet to be found are ongoing.

The repatriated remains are returning to the United States as individual families make burial arrangements. Cpl. Mason O. Yarbrough’s family were the first to lay their loved one to rest on Dec. 15, 2000, in Sikeston, Mo. Several of the families have opted for joint interment at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C., scheduled for August 2001.

Among those laid to rest at Arlington will be Sgt. Clyde Thomason, killed during the raid as he became the first enlisted Marine in World War II to earn the Medal of Honor. His younger brother, Hugh, who followed his elder sibling into the Marines and served during World War II and Korea, sums up the general feeling of many of the families.

“He was a fine young man and we are quite gratified to finally be able to bring him home,” says Thomason.

Shirley Anderson, great niece of Cpl. Yarbrough, says that the return of her great uncle finally brings closure to their family after so many years

Home At Last – Rest In Peace

Gerald P. Holtom

Captain, United States Marine Corps

Palo Alto, California

Clyde Thomason

Sergeant, United States Marine Corps

Atlanta, Georgia

Vernon L. Castle

Field Musician First Class, United States Marine Corps

Stillwater, Oklahoma

Daniel A. Gaston

Corporal, United States Marine Corps

Galveston, Texas

Edward Maciejewski

Corporal, United States Marine Corps

Chicago, Illinois

Robert B. Pearson

Corporal, United States Marine Corps

Lafayette, California

William A. Gallagher

Private First Class, United States Marine Corps

Wyandotte, Michigan

Kenneth M. Montgomery

Private First Class, United States Marine Corps

Eden, Wisconsin

John E. Vandenberg

Private First Class, United States Marine Corps

Kenosha, Wisconsin

Carlyle O. Larson

Private, United States Marine Corps

Glenwood, Minnesota

Robert B. Maulding

Private, United States Marine Corps

Vista, California

Franklin M. Nodland

Private, United States Marine Corps

Marshalltown, Iowa

Charles A. Selby

Private, United States Marine Corps

Ontonagon, Michigan

On Thursday, August 16, 2001 our firm was honored to serve the United Sates Marine Corp Casualty Affairs. We provided transportation from Andrews Air Force Base at ARLINGTON FUNERAL HOME, and housed overnight 13 casketed remains of World War II Marines killed in action on August 17, 1942 on the Makin Atoll the Gilbert Islands in the South Pacific. Moreover on August 17, we again provided transportation for their remains to be transported to their final resting place at Arlington National Cemetery.

It was an endeavor that gave us immense gratitude, and patriotic loyalty in serving those who, so many years ago, served us to protect our freedom. Our staff would like to thank the following for their assistance which made the entire transition flawless:

Old Town Funeral Choices, Alexandria, VA; Lee Funeral Home, Manassas, VA; Huntt Funeral Home, Waldorf, MD; Lacy Funeral Home, Louisa, VA; Lindsey Funeral Home, Harrisonburg, VA; Bacon Funeral Home, Washington, D.C.; Frazier’s Funeral Home, Washington, D.C.; Danzansky-Goldberg Memorial Chapels, Rockville, MD; At Need Funeral Transfer Services, Washington, D.C.; The Officers and Troopers of the Maryland and Virginia State Police, and the support we always receive from the Arlington County Police. Thanks to all.

Charles Carey and William Halyak

Management, Arlington Funeral Home

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard