Lewis B Puller, Jr., who transformed his years of struggle with physical and emotional ravages of Vietnam War into a Pulitzer Prize-winning autobiography, shot and killed himself yesterday (11 May 1994) at his Fairfax Country, Virginia, home. He had lost his legs and parts of both hands when he stepped on an enemy land mine in Vietnam as a Marine officer in 1968. He told story of his ordeal and its agonizing aftermath in an inspiring book titled “Fortunate Son,” account that ended with triumphing over physical disabilities and emotionally at peace with himself.

He spent last months of his life in turmoil, friends and associates said. In recent days, they say, fought a losing battle with alcoholism, a disease he had kept at bay for 13 years, and struggled with a more recent addiction, to painkillers initially prescribed to dull continuing pain from his wounds. Friends said he and his wife, Linda T. (Toddy) Puller, a member of the Virginia House of Delegates, had separated shortly before his death. Fairfax country police released few details of suicide.

He was alone, and his body was found in the afternoon by members of his family. “To the list of names of victims of the Vietnam War, add the name of Lewis Puller,” Toddy Puller said in statement. “He suffered terrible wounds that never really healed.”

Though Puller spent only a short time in combat, his life from beginning to end never strayed far from the armed services. His father was the legendary Lewis (Chesty) Puller Sr, whose heroism in the Pacific during WWII made him the most decorated Marine in history. The younger Puller went to Vietnam as a Marine lieutenant and spent many years as a lawyer at the Pentagon. He remained a prominent veterans activist until his death. But it was his harrowing experience in Vietnam that defined his life.

After the land mine explosion on October 11, 1968, that riddled his body with shrapnel, he lingered near death for days and his weight dropped to 55 pounds. He survived, those who knew him say, primarily because of his iron will and his stubborn refusal to die. For years after he returned to reasonably sound physical condition, the emotional ground underneath him remained shaky. Though he got a law degree and mounted an unsuccessful campaign for Congress in eastern Virginia, he battled black periods of despondency. He drank heavily until 1981, when he underwent treatment for alcoholism.

Family friends said yesterday that Puller’s marriage began to unravel earlier this year when he began drinking again. Shortly before his book won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992, his wife was elected to the Virginia Legislature and began spending time in Richmond.

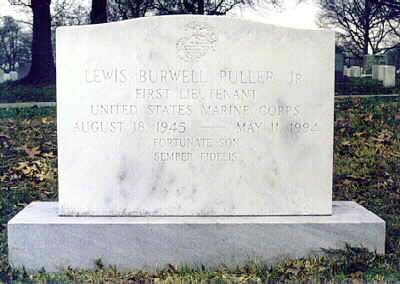

In addition to his wife, survivors include their two children, Lewis III, 25, and Maggie, 23; and his twin sister, Martha Downs. Although arrangement were not complete, Toddy Puller said in her statement that “interment will be in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors, as was his wish.”

He did not have an easy or comfortable life, but yesterday he was remembered as a man who defeated the demons of alcoholism and depression and brought comfort and understanding to many through his Pulitzer Prize-winning book. “He said he envied those people who had a faith that came without any sorrow, faith that came without wavering,” recalled the Reverend Robert W. Prichard, who delivered the homily at the funeral services. “He envied it for others, but he couldn’t claim it for himself.”

He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. A caisson drawn by six white horses and led by a seventh escorted his remains to the grave. As is the custom, the casket was draped in a U.S. flag. A Marine Corps honor guard led the way through the cemetery as members of the Marine Corps Band kept time. National, state and local lawmakers joined nearly 700 people paying their respects. An overflow crowds spilled out onto the grounds of Fort Myer Chapel. More than a dozen of the attendees were in wheelchairs, as Puller had been before his death.

Prichard said most of the people who knew Puller wished that his life had been different, that his book, “Fortunate Son,” would have propelled him from his despair. “We all wanted it that way,” Prichard said. “From weakness to strength, from height to height, from victory to victory.” But that was not to be. Terry Anderson, a former Associated Press journalist who was held hostage in Lebanon, recalled the same hope he had had for his friend, Puller. “This is a man who had so many burdens, so many things to bear. And he bore them well for 25 years,” he said. “What did I miss?” Anderson asked. “I was his friend. I thought he was winning.”

During his military career, Puller earned the Silver Star, two Purple Hearts, the Navy Commendation Medal and the Vietnam Cross of Gallantry. He earned a law degree at the College of William and Mary and had been an attorney at Defense Department. He recently had taken a 2-year leave of absence to be a writer-in-residence in the communications department at George Mason University.

In a statement yesterday, Linda Puller said, “Our family has been moved and humbled by the outpouring of affection for Lewis. The many acts of kindness from our friends across the country have helped us in this very difficult time. It is clear that Lewis affected the lives of people in ways that we never knew.” In a final act of giving, Puller became organ donor, said Supervisor Gerald W. Hyland, D-Mount Vernon District. “Yesterday morning, I sat in the waiting room at Washington Hospital Center transplant section,” he said. “I saw a sign that read ‘In death, there is life. Donate organs.’ Lewis Puller donated his organs and was successful in having that occur.”

“He was a terribly intelligent person whose pain, apparently, he could not endure any longer,” Hyland said. “It’s so sad that the conflict in Vietnam has taken another victim. Although Lew Puller has died, he has truly left his mark on America.”

Lewis Burwell Puller, Jr picked up a gun one afternoon last May and killed himself. He was 48, a winner of the Pulitzer Prize for his 1991 autobiography, “Fortunate Son: The Healing of a Vietnam Vet.” His father was the late General Chesty Puller, the most decorated Marine in history. To those who fought in Vietnam, the son displayed a different kind of heroism -attesting to the horror of war. I never met or talked to Lew Puller, but I knew him, the woeful part of him anyway.

We fought on the same ground at the same time, I-Corps, Vietnam, in the bloody year 1968. I came home whole however. He came home a mess, both legs gone, hands mangled, guts in a knot, his loss literally the result of a misstep, a booby trap. His recovery – if it can be called that – was long and hard. Between operations and hospital stays, he fought addictions to liquor and painkillers. Along the way, he tried to commit suicide but got so drunk preparing himself he failed. He didn’t make the same mistake twice. His friends and family said he had been despondent over the breakup of his marriage and a certain inertia that had crept into his life. But I think it might have been something else. For men with blood on their hands, men strained by the butchery of combat, the real fight for survival starts when the guns grow silent. For us, suicide is a chronic afterthought, a dark idea that follows dark memories. Most of us resist the incessant impulse to destroy ourselves, but many of our comrades, too many, do not. They lose the war long after the fighting has stopped. At the very end of his book -in his last line, in fact – Lew Puller takes as his coda a lesson he learned along his way: “Often the only way to keep that which we hold most dear is to give it away.” He was talking about his medals. Or was he?

He now lies at rest in Section 3, Grave Number 2229 of Arlington National Cemetery.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard