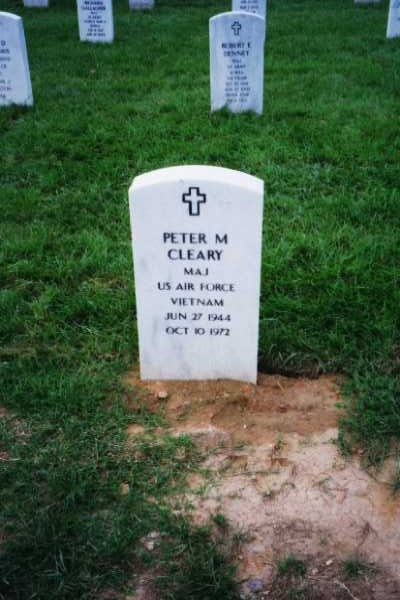

Peter McArthur Cleary was born on June 27, 1944 and joined the Armed Forces while in Colchester, Connecticut.

He served in the United States Air Force and attained the rank of Major.

Peter McArthur Cleary is listed as Missing in Action.

HARTFORD COURANT

Rifle shots pierced the quiet at Arlington National Cemetery Friday morning, followed by the mournful notes of taps sounded by a lone bugler. Graying veterans wiped away tears as a white-gloved team of eight airmen gingerly folded the American flag that had been draped over the casket of Air Force Major Peter Cleary.

The flag, tightly folded into a perfect triangle, was then presented by Lieutenant General Joseph H. Wehrle Jr. to Sean Cleary, who last saw his father 29 years ago when Sean was just 4. In 1972, Peter Cleary failed to return from a mission while serving in Vietnam.

For all that time, the family had no grave on which to place flowers, no certainty of what really happened to him. Then, two months ago, the Air Force told the family it had positively identified his remains. Military officials say they believe Cleary’s F-4

Phantom fighter was hit by a ground-to-air missile on Oct. 10, 1972, and crashed into the mountains in North Vietnam near the Laotian border.

Sean Cleary took the flag from Wehrle and clutched it.

“It’s been a day we’ve waited a long time for,” he said after the service. “It’s just an incredible feeling of closure to finally have a place we can visit.”

Peter Cleary was buried on a hillside dotted with evergreens with a clear view of the Pentagon. Nearly 200 friends, relatives, veterans and Air Force personnel walked behind a caisson pulled by five dark-brown horses as it rolled from the Memorial Chapel to the gravesite in Arlington, where 270,000 other veterans and their spouses are buried. An 18-piece Air Force band accompanied the caisson, a single drum beating a cadence. Mourners filed past countless graves and scattered daffodils on a overcast day. They were accompanied by 45 other airmen, including a color guard and seven-member honor guard, who each fired three shots in tribute.

As family and friends left the grave, some paused to place white flowers atop the casket.

Wehrle, now a three-star general, flew with Peter Cleary and played basketball with him. He was waiting with a bottle of champagne that fall day in 1972, waiting for Cleary to return to the base at Udorn Airfield in Thailand. Congratulations were in

order because it was Cleary’s last mission before he was to return home.

“We said, ‘We ought to be hearing from him,’ and there was nothing,” Wehrle said. “He never showed up.”

Among other veterans who joined Wehrle at Cleary’s funeral Friday was retired four-star General Lloyd Newton, who lives in Connecticut and works at Pratt & Whitney. Newton recalled working with Cleary on a project designed to relieve racial tension in the military.

“He had respect and dignity for people,” Newton said. “Not only was he a great pilot and great warrior, but he had a sense of human decency, and that’s what made him special.”

Since 1992, when the military’s Joint Task Force – Full Accounting and the Army’s Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii were formed, 537 sets of remains have been returned to the United States. Nearly 2,000 Americans, including 31 Connecticut residents, are still unaccounted for from the Vietnam War.

“We will never rest until all the veterans are found,” said Rep. Rob Simmons, R-2nd District, a Vietnam veteran who attended Friday’s funeral. State Rep. Linda Orange, D-Colchester, state Sen. Eileen Daily, D-East Haddam, and Colchester First Selectwoman Jenny Contois also attended.

Lori Grenfell of West Haven, a Vietnam veteran, had worn a missing-in-action bracelet for Peter Cleary since 1975. She will finally take it off and give the bracelet to his children.

“He’s home, he’s finally home,” Grenfell said.

Back in Connecticut, flags were flown at half-staff as Gov. John G. Rowland declared Friday a statewide day of mourning in Cleary’s memory.

The three decades that have passed since Cleary crashed have not erased his family’s memories.

“I can still picture that Irish, devilish, how-can-you-get-mad-at-me grin,” Peter Cleary’s brother, Tom Cleary, of Colchester, said during his eulogy.

Tom Cleary said his brother, who liked to sing folk music at coffeehouses, had a zest for life that made him “so much more than a fighter pilot.”

Tom Cleary has spoken frequently over the years about the feelings of families with relatives missing in action in Vietnam. Still, he said, he struggled to write the five-minute eulogy he prepared for his brother.

“Those were all a dress rehearsal for this one,” he said.

For Sean Cleary, memories of his father are few.

He remembers the day he came home from playing at a friend’s house and his father gave him his first bicycle. He remembers spending a Christmas in the South with his family, and how his father laughed that it was snowing back home in Connecticut.

Peter Cleary leaves three grandchildren, including his daughter Paige’s 3-year-old son, who is named after him. A fourth grandchild is on the way. His parents, Helen and John Cleary, both died before learning that their son’s remains had been found.

“This has been an emotional roller coaster ride,” Paige Cleary said Friday. “On the one hand, it’s closure, then on the other, it rips the wound right open again. But it will heal more solidly, I guess.”

Over the years, the family received several false reports that authorities had found Peter Cleary’s crash site and his remains. There was also a middle-of-the-night phone call to his brother Tom from a man who said he worked for a clandestine

organization and that Peter Cleary was still alive, being kept as a slave in Cambodia.

This week, for the first time, Peter Cleary’s two brothers, Tom and Bill Cleary, sat down in a hotel room and talked about how they had dealt with their brother’s disappearance differently.

Tom Cleary had always held out hope. His brother didn’t.

“I always said he was killed,” said Bill Cleary, also a Vietnam veteran. He wept as he walked from his brother’s casket.

“I always said he was missing,” Tom Cleary said. “I couldn’t take that step. Now we can. There is no mystery.”

In his eulogy, Tom Cleary told Paige and Sean that their father did not die in vain. And he told Peter Cleary that his family, friends, neighbors and nation still remember him.

“You were never forgotten,” he said. “May you rest in peace in this sacred place of honor.”

Colchester veteran is buried in Arlington

Cleary family, friends finally grieve for their fallen hero

Norwich Bulletin: 13 April 2002

AT LAST, AT PEACE

U.S. Air Force Maj. Peter Cleary finally got his last wish.

Nearly 30 years after the F-4 Phantom jet he was flying disappeared over North Vietnam, the Colchester resident was buried Friday with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery as more than 100 of his family, friends and fellow veterans mourned.

Cleary, 28 when his plane disappeared October 10, 1972, had been missing in action until February, when military officials were able to confirm, through DNA tests, that remains recovered in 1984 were his. Evidence shows a land-to-air missile hit Cleary’s plane, crashing it into a mountaintop in North Vietnam.

The brave, fun-loving, Irish-American pilot who loved fast planes and fast cars had asked his family to bury him at Arlington if he were killed in the war.

“This has been a day we’ve waited for for so long,” Sean Cleary, Peter Cleary’s son, said. The 33-year-old was just 4 when his father disappeared and now has a 2-year-old daughter of his own. “It’s just an incredible feeling of closure to finally have a place we can go to visit.”

For nearly three decades, Cleary’s parents, wife, two children and three siblings longed to know whether Peter Cleary was dead or had been taken prisoner. Cleary’s parents died before they had a chance to learn their son’s fate.

“They’re together now,” Sean Cleary said.

Thomas Cleary, who delivered the eulogy for his brother from the altar of Fort Myers Chapel, said he wanted people to remember Peter as more than just a decorated war hero. Peter Cleary earned three Distinguished Flying Crosses, 10 Air Medals and the Purple Heart.

‘Zest for life’

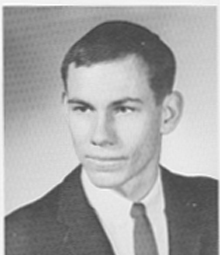

Before becoming a pilot, Cleary briefly studied to be a priest and had a reputation as a lovable mischief-maker, Thomas Cleary said.

“We remember a guy with a zest for life,” he said, describing Peter’s smile as “an Irish, devilish, how-can-you-get-mad-at-me grin.”

After the funeral Mass, Cleary’s family and friends followed a horse-drawn wagon carrying the pilot’s coffin to a grave inside the 612-acre cemetery. Sean Cleary, his younger sister, Paige, and their mother, Barbara, placed white roses on the casket after the honor guard had carefully folded the American flag that had draped the casket and presented it to Sean.

Vietnam veterans, many of whom had traveled by bus from Connecticut, hugged one another and wept.

Sean Cleary said he has just two distinct memories of his father.

“They’re both funny of course, which people tell me is typical of my father,” he said. “The first is him surprising me with my first bicycle, which, as a 4-year-old, was a blast. The second was sitting outside with him at Christmas time by a pool in the

Philippines and me asking him what snow was.”

Colchester home

U.S. Rep. Rob Simmons, R-2nd District, himself a decorated Vietnam War veteran, said Cleary’s family kept telling him it seemed like only yesterday that Cleary was alive.

“The sadness and the grieving here are just as real as they would have been 29 years ago,” the congressman said.

Sean Cleary said the Vietnam War still isn’t over for his family, despite the peace they feel from having finally laid his father to rest.

“There are still well over 1,400 service men and women left behind and unaccounted for,” he said. “It would be very selfish for my family to say the war is over when it’s still not over for so many others.”

Peter Cleary always considered Colchester his hometown, said Thomas Cleary, who still lives there and whose parents lived there until their deaths. Flags in Colchester flew at half staff Friday in honor of Cleary.

Peter attended grade school in Colchester and spent his freshman and sophomore years at St. Bernard High School in Montville before graduating from Mother of the Savior Seminary in Blackwood, N.J., in 1962.

He later studied for the priesthood at St. Edmund’s in Mystic. He left after a year and transferred to St. Michael’s College in Winooski, Vt., where he graduated in 1967 with a bachelor’s degree in English.

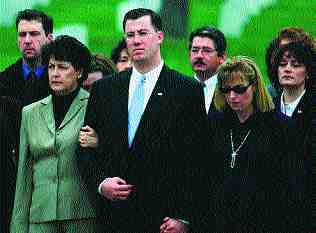

Sean Cleary, center with his wife, Beth, right, and his mother, Barbara, left,

attends a funeral for his father in Arlington National Cemetery Friday.

Bobby Easton, a member of the Connecticut Rolling Flags, a MIA-POW group, pays

his last respects at the funeral for U.S. Air Force Major Peter Cleary at Arlington

National Cemetery. Peter Cleary had been missing since 1972, when his plane

was shot down over North Vietnam.

Colchester family finally gets the truth about Viet vet missing 29 years

A Colchester, Connecticut, family, tormented for nearly three decades about the whereabouts of a U.S. Air Force major who disappeared in Vietnam, hasfinally found peace.

Thomas Cleary, the brother of Major Peter Cleary, learned last week that the military identified the remains of the airman who died on October 10, 1972, when his fighter plane crashed into the mountains of northern Vietnam.

“None of us had peace on this, ever,” Cleary said. “This is a gift to us. After 29 years of uncertainty, we finally know Pete’s fate and all the questions are gone.”

The family suffered over the years with false reports of Cleary’s remains being found at the crash site. Once, the family was told incorrectly that his remains and dog tags were located by a North Vietnamese refugee.

For Thomas Cleary, the worst was a phone call at night from a man who claimed to have worked for a clandestine organization, reporting that Peter Cleary was kept as a slave in Cambodia.

Johnie Webb, deputy director of the U.S. Army’s Central Identification Laboratory

in Hawaii, said final DNA tests on the remains of both Cleary and his navigator, Captain Leonardo Leonor, were completed last year. Officials wanted to be

absolutely sure of their identity before informing relatives.

“The worst thing we could do is give the family the wrong identification,” Webb

said.

Cleary’s mother, Helen, died in March 2001, never knowing of her son’s fate.

For 20 years, she wore a silver missing-in-action bracelet bearing the name of her

first-born son. She finally removed it in 1992.

After her death, Cleary found the bracelet, so worn that it broke in half at its

touch.

“My mom kept her sanity by just believing he was dead, yet she wore that

bracelet,” Cleary said.

Peter Cleary’s children, who were toddlers when their father vanished, grew up

knowing him only from photographs. His daughter, Paige, studied at St. Michael’s

College in Vermont because her father did, and named her first child after him.

“It broke my heart one day when she was 3 and she asked me if I was her daddy,” Cleary said.

The issue of U.S. troops missing in action in Vietnam, which prolonged the pain long after the United States quit Saigon in April 1975, has subsided with time and efforts by a military task force that visited Vietnam as relations with the former enemy have normalized.

Since the task force was established in 1992, 537 sets of remains have been turned to the United States. Nearly 2,000 Americans, including 31 Connecticut residents, remain unaccounted.

Peter Cleary was on temporary duty at Udorn Royal Thai Air Base in Thailand when he left on his final fighter mission. With him was his best friend, Leonor who had completed his tour of duty and had even gone home to the Philippines. He returned to fly one last mission with Cleary.

The U.S. Air Force searched unsuccessfully for the men and the crash site for two days.

In early 1973, the Cleary family wept when they learned that Peter’s name was not among prisoners of war being released.

Six years later, Peter Cleary was declared killed in action after investigations failed to find evidence that he might be alive. His wife, Barbara, remarried.

Peter Cleary’s remains will be buried with military honors at Arlington National

Cemetery in April, fulfilling a wish he expressed when he went to war. Veterans in

Colchester plan a ceremony in his honor at the town’s Vietnam Memorial.

“My brother, Peter Cleary, is coming home,” Thomas said.

Courtesy of the GateHouse News Service

After nearly three decades of waiting for word on their loved one, the Cleary family finally got some answers and some healing. That healing process continued with a ceremony this past Saturday at Fort Sewall.

Marblehead’s Major Peter M. Cleary’s plane was shot down 15 minutes before his mission was to end in 1973. He then went missing in action for 29 years.

Cleary’s remains were discovered at the Vietnam crash site in 2002, and he was laid to rest shortly thereafter at Arlington National Cemetery as per his wishes. Yet, until recently, a plaque in his honor at Fort Sewall indicated he was still missing. In an effort led by town Veterans Agent David Rodgers, the plaque was updated and rededicated Saturday.

The town first planted a tree in honor of Cleary in 1973 and dedicated a plaque at the site, which read, “The Freedom Tree, with the vision of universal freedom for all mankind, Major Peter M. Cleary, USAF.” The plaque went on to describe Cleary’s missing-in-action status during the Vietnam War in 1972. Coincidentally, noted Rodgers, the original tree died shortly before Cleary’s remains were found.

The updated plaque states that Cleary’s remains were recovered and laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery on April 12, 2002. The plaque also honors all prisoners of war and all those soldiers missing in action.

Marblehead dignitaries joining the Cleary family were Veterans Agent David Rodgers, who organized the event, state Rep. Doug Petersen, Chairman of the Board of Selectmen and Vietnam veteran Harry Christensen and his colleague, Selectman Judy Jacobi.

Rodgers opened up the ceremony by noting he was honored to be representing the town and the Veterans of Foreign Wars and said that the new plaque “brings closure, for the family and the town.”

Christensen added, “For those of us who struggled through the terrible war and the terrible jungle that was Vietnam, we made sure that (our fallen brethren) were recognized. I am proud to be here and pleased to see a remembrance for Peter Cleary.”

He then instructed the crowd, “Take a deep breath and look up at the sky. What you’re experiencing is freedom, and we need to remember those who paid for it.”

Also in attendance — as he was back in 1973 when the original tree was dedicated — was U.S. Naval Commander Timothy Sullivan, who was shot down with fellow pilot Paul Schultz over North Vietnam in November 1967. Both crewmen were captured and held for over five years as prisoners of war.

Sullivan said, “When I first got back from Vietnam, everyone was concerned about those soldiers who were missing in action. People got the ball rolling with tree plantings such as this one.”

Sullivan said the grassroots efforts of people back at home holding tree plantings, displaying the POW/MIA flags and other public displays forced the government to become more accountable for its troops.

“If it weren’t for people in every city and every town planting trees, holding ceremonies, these soldiers wouldn’t be accounted for,” he said. “If you ever wore a POW/MIA bracelet, for myself and for everyone else (who served in Vietnam), I thank you. This action and other ceremonies put pressure on the politicians to come up with an answer for the people and find those missing.”

Following a 21-gun salute, a flag was presented to Mrs. Cleary, and flowers were presented to her daughter, Paige Cleary-Somol. Paige’s children, Peter (who was named after his grandfather), Ashlee and Kendall also attended at the event. The Clearys also have a son, Sean, who lives in White Plains, New York. Sean has two children, one of whom took Major Cleary’s middle name, MacArthur, as his middle name.

Paige said, “We always had an agreement that whoever had the first boy would take the name ‘Peter’ and whoever had the second boy would take the middle name ‘MacArthur’ to carry on my dad’s name.”

Cleary-Somol said that, because there was no gravesite for her father prior to 2002, she and her family would always come to visit the tree and plaque, because “all we had was the tree and the plaque to visit and remember him.” She remembered early in 2002 when her uncle Tom, Peter’s brother, called to tell her that it didn’t look like the tree would survive. Shortly thereafter, Cleary’s remains were discovered.

“The timing is amazing,” she said. “I was thinking, ‘Leave it to Daddy, it’s a beautiful thing for him to time it like that.’”

She thanked Rodgers, who “always does a good job as far as honoring the veterans.”

Paige wasn’t much older than her youngest daughter Kendall is now at the time that her father’s plane was shot down in Vietnam.

Cleary-Somol said, “The term ‘closure’ doesn’t accurately describe what we went through. I see it more as ripping open all the old wounds and allowing it to heal properly. It’s raw and it’s painful.”

Peter’s wife, Barbara, was in the Philippines with her two young children at the time, and recalled being nervous the day of her husband’s final flight but then felt relief later in the afternoon, thinking she would have been notified if anything had gone wrong. Then she got the fateful phone call from the squadron commander at 11 that night, informing her that her husband’s plane had been shot down at 5:45 that evening and that he was missing.

Every detail of that day remains vivid, even after all these years:

“One of his comrades was waiting on the tarmac for him with a bottle of champagne,” Barbara recalled. “He had a really difficult time with it.”

Paige said that, growing up, she didn’t know whether that story had been exaggerated, but it was brought up during Cleary’s burial ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery.

The Cleary family had already packed prior to Peter’s final mission, ready for their new assignment at Seymour Johnson Base in North Carolina. Major Cleary planned to leave the service not long thereafter, with Marblehead as the family’s final destination.

The three Clearys made the trip to Logan, complete with rabies serum to be administered due to the wild dogs in the Philippines. They moved in with Barbara’s sister and brother-in-law for seven months. Barbara now lives in Concord, where her sister and brother-in-law reside.

Barbara explained that her husband’s remains could be identified because of a medal of St. Michael, the patron saint of warriors, which he wore — against regulations — on his missions. A Vietnamese man discovered the medal and turned it in to the authorities. The man then led the forensic team to the site, where Major Cleary’s remains were positively identified. Barbara now has the medal with her at all times, along with a medal of St. Jude (which brings safety to travelers) and her wedding band from her marriage to Cleary.

Cleary’s brother, Tom, also had a story to share.

“My mom had an MIA/POW bracelet, and at the time we were seeking accountability for our missing troops — we never knew if Peter or the other soldiers were prisoners of war or if they were even alive,” he said. “My mother had her bracelet silver-plated, and she wore it for over 20 years until someone counseled her to take it off, that it was time to let go, and that having this bracelet on her wrist every day was a constant reminder of Peter. She finally took it off in 1993. She died in 2001. In 2002, I was going through her belongings right around the time that Peter’s remains were discovered. I picked up the bracelet, and it broke in two.”

Rodgers said he would be remiss if he did not mention three of Marblehead’s troops who are presumed dead and unaccounted for: Warren Bowles of the U.S. Navy, Harry E. McCann and Warren P. Smith, both of the United States Air Force. He also acknowledged Colleen Piper, widow of Special Forces Staff Sergeant Chris Piper, who died in Afghanistan on his third tour of duty in 2005, and their son Christopher, who attended Saturday’s services.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard