Courtesy of the Washington Post

28 September 2001

‘These Guys Are Heroes Every Day’

Funerals Honor Two Pentagon Navy Officers

A caisson carries the casket of Commander Patrick Dunn during funeral services at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia

Navy pallbearers carry the casket of Commander Patrick Dunn during funeral services at Arlington National Cemetery

A lone bugler play Taps during the graveside funeral for Commander Patrick Dunn during funeral services at Arlington National Cemetery

Stephanie Dunn, widow of Commander Patrick Dunn gets a kiss from a U.S. naval officer during funeral services at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Va. Thursday, September. 27, 2001. Dunn, who worked in the Navy Command Center at the Pentagon, died in the September 11 terrorist attack at the Pentagon

Stephanie Dunn, widow of Commander Patrick Dunn, holds a flag and wipes her eyes during funeral services at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, Thursday, September 27, 2001. Dunn, who worked in the Navy Command Center at the Pentagon, died in the September 11 terrorist attack at the Pentagon.

he sailor’s widow paused for a second as the funeral cortege came to a halt.

She stood in a short-sleeved black dress, with her hands clasped, gazing at her husband’s coffin, which was being drawn before her by six gray horses.

To her right, just beyond some trees, loomed the fire-scarred Pentagon, where he had worked 16 days ago. On her left was his grave, beside which she was about to sit in a chair covered with velvet. Behind her shuffled a column of mourners in dark

clothes and Navy white.

For a moment yesterday, Stephanie Ross Dunn, 31, a native of Pittsburgh and marketing assistant pregnant with her first child, stood under a threatening sky in Arlington National Cemetery, at the center of national grief.

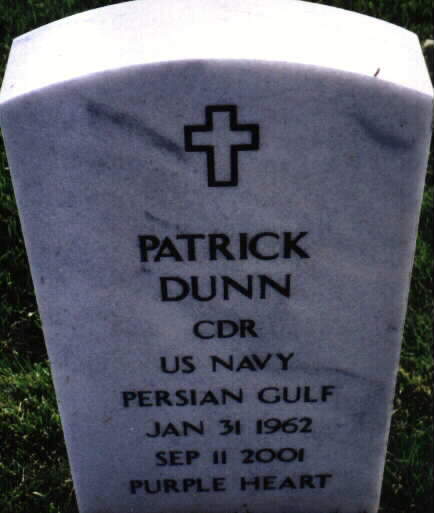

Her husband, Navy Commander Patrick Dunn, 39, of Springfield, was killed in the September 11 terrorist attack on the Pentagon.

And now he was being laid to rest, one of the first Pentagon victims to be buried at Arlington, within eyesight and earshot of where he and 188 others died, and moments before the funeral of another Navy victim, Lieutenant Commander Otis Vincent Tolbert, of Lorton, Virginia.

Stephanie Dunn turned from the Pentagon yesterday, andthe entourage gathered around her husband’s grave with their backs to the charred structure, focused, instead, on the life of a man who she said was among the happiest on earth.

And, indeed, he was, said the fellow Navy officers who gathered by the score in their dress whites, gold shoulder boards, and black armbands to bid farewell.

The son of a Newark policeman, Dunn always had a joke up his sleeve. He could make a short story delightfully long, a good yarn better.

“He had a great sense of humor,” said Lieutenant Commander Robert Keane, the Naval Academy’s senior Catholic chaplain, who helped celebrate the funeral Mass and had served with Dunn in Italy two years ago.

Keane recalled how, in Italy, Dunn used zany techniques to motivate the crew of the USS LaSalle, on which Dunn was theexecutive officer, during the morning cleanup hour.

“He would sometimes put on a different uniform just to get their attention,” Keane remembered. “One day he showed up at mydoor. He had on a T-shirt with a . . . sidearm and a canteen, and a pith helmet. I said, ‘Pat, where did you get that outfit?’ Hesaid, ‘I just thought it was cool.’ “

Not far away, friends and family were remembering the life of Navy Lieutenant Commander Otis Vincent Tolbert, 38.

Two other Pentagon victims were buried in Arlington earlier in the week, but their services were private, Arlington cemetery officials said. Twenty-five more such burials are scheduled, and the officials said they did not know how many Sept. 11 victims

eligible for Arlington burials would ultimately be laid to rest there.

In general, burial in Arlington is limited to those who have served in the military and their spouses. But there are a few other ways to be eligible, and the cemetery officials said Arlington is considering Pentagon burial requests on a case-by-case basis.

Dunn’s services, conducted with somber Navy pomp, began at 12:45 p.m. when his flag-covered silver and gray casket was borne from a black hearse by a Navy honor guard into the small brick chapel at Fort Myer, adjacent to the cemetery.

Inside, beneath six brass-colored chandeliers, the church was packed, with Navy officers in white and Marine Corps officers, in their black tunics and blue trousers, spilling into the aisles and vestibule.

Keane conducted the service, along with Captain George Pucciarelli, who was a Catholic chaplain at the Naval Academy when Dunn was graduated in 1985.

Afterward, Dunn’s coffin was placed on the horse-drawn caisson and, followed on foot by his wife and the other mourners, wound its way among the thousands of other headstones to his resting place.

There, his wife took her seat. They’d been married less than two years, she’d said earlier. But it had been joyous. And this, with its reverence and tradition, was what Pat would have wanted.

“It’s not just me or his family who are mourning,” Stephanie Dunn had said in an interview Sunday. “It’s the whole nation. It’s the whole Navy family. . . . It’s the world. They need to be able to see this, too.”

After the band played some hymns, the honor guard fired a rifle salute, and a sailor in the distance played taps. They handed her a folded flag, and admirals came over to hug her. She looked weary but smiled.

After a moment, she got up, went to the coffin and kissed the lid. Then, clutching the flag, she took an officer’s arm and walked through the grass back to the car that would take her home.

She never seemed to notice the Pentagon.

Patrick Dunn

Thursday, September 27, 2001

From her home, Stephanie Ross Dunn could hear when the USS LaSalle was heading out to sea: Three deep blasts of its horn as it left its berth, one more as it turned for the Gulf of Gaeta.

She’d grab her big blue-and-gold Naval Academy flag and head for the roof of the house in the small Italian port she shared with her husband, Pat, the LaSalle’s executive officer. And when the stately command ship passed by, with her husband on the bridge, she’d grasp the flag by its wooden staff and wave a solitary farewell — to him, and to all hands on board.

Despite his busy life in the Navy, Commander Patrick Dunn, 39, and his wife were in constant communication.

The morning of September 11, 2001, he kissed Stephanie, 31, who is two months pregnant with their first child, before leaving for work at the Pentagon. Then, for the first time, he kissed her stomach, too.

He telephoned later to tell of the terrorist attacks in New York City. After the Pentagon was hit, when he didn’t call back, something told her quickly, starkly and clearly that he was gone.

On Sunday, as she sat in the living room of their Springfield town house wearing her husband’s sapphire Naval Academy ring on a necklace, she spoke of life married to a sailor.

Pat, the son of a Newark policeman, came from a Navy family. His father served in World War II and the Korean War, and Pat and one of his brothers were Naval Academy graduates.

“Pat’s favorite thing was to be at sea,” Stephanie said. “He loved to be at sea. He . . . absolutely loved it. His home was at the sea. If the ship was rocking, he was happy. . . . It was in his blood.”

He had just come off several long sea deployments when they met at a sports bar in Alexandria, she remembered, four years ago last week.

But he also was fascinated with the lore and excitement of the Pentagon, where he worked as a planner and strategist, and where he was when the hijacked Boeing 757 airliner smashed into the Navy Command Center on September 11.

“It was like almost part of me left,” Stephanie said of the moment when she learned of the Pentagon attack. “I covered my mouth and I screamed, ‘No!’ It’s like my body knew, and I don’t know how to describe it. . . . But part of me left with him. I knew right away — my life had just changed.”

Commander Dunn will be buried today at Arlington National Cemetery.

A Pentagon Father’s Daughter

6 Months After Fatal Attack, a Love Story’s New Chapter Begins

Courtesy of The Washington Post

Sunday, March 17, 2002

Alexandria Patricia Dunn was born at 9:42 Friday night — 21:42 Navy time — in maternity Suite 18 at Bethesda’s National Naval Medical Center, which overlooks the Navy Exchange.

She was welcomed into the world by her pale and exhausted mother, Stephanie, 32, two grandparents and an uncle. She weighed 7 pounds 5 ounces, and everyone said she had the red hair and features of her father, Patrick.

He was not present. At least physically. Killed on September 11 in the Pentagon, he was there in a framed photograph his wife had placed on a table in the room when she began her labor about eight hours before: a handsome man with a jaunty face in the uniform of a naval officer.

He would have relished the birth of his first child and perhaps stepped somewhere for a good cigar. His little girl, named after him and the town where he and his wife met, was pink and exquisite to the last detail.

But she was more, too. She was a vestige of the time before September 11, a kind of salve over the wound of that awful day, and a reminder, against the savagery of those acts, of the majesty of life.

Her advent had also been a solace to her grieving mother — they had kept each other alive, she said — and her arrival on balmy Friday night was, in a way, the reincarnation of a lost husband.

The last six months had been chaotic for Stephanie Dunn and her family.

She had suffered anguished hours of not knowing whether her husband was alive. She had led mourners at his funeral at Arlington National Cemetery. Her father had later suffered a stroke. Her husband’s father had died. She had twice been to the White House.

And she was constantly reminded of her tragedy. The empty chair in the examining room at the doctor’s. The highlighted words at the top of her medical record: “Husband Killed in the Pentagon.” The hospital wristband she wore Friday night that said: “USN FAM MBR DEC” — deceased.

Over time, she had come to terms, of sorts, with the fact that she would have the baby, rear her and live the rest of her life without the man to whom she had been married for less than two years. She had lost her future, she would say.

An amiable person with blue eyes, frosted blond hair and a quick wit, she also wished her story to be shared: for her daughter, for her husband, for his beloved Navy and for all those who suffered at the Pentagon when the hijacked airliner slammed into the building September 11.

And over the last few months, in a living room rocking chair, in her doctor’s office and as evening fell Friday in the hospital delivery room, she told, in chapters, of a life damaged, and now under repair.

A Friend of a Friend

Jack Morrissey’s idea had been for Stephanie to meet another guy that night at the bar in Old Town.

Morrissey, 48, a U.S. Capitol Police officer and Boston native, was a little too old for Stephanie. But he knew another Boston guy he thought she might like.

She was then Stephanie Ross, 27, one of two children of a Pittsburgh business executive. She had met Morrissey at Alexandria’s Foxchase apartment complex, where they both lived. Stephanie had arrived in town a few years before with her college cat, Bandit. She had moved in with some sorority sisters for a while, then gotten a place in Jack’s building.

She used to hear Jack talk about the Penalty Box, where he would go and watch hockey and have beer and pizza. It sounded terrific. It was run by Bryan Watson, an old NHL hockey player with a beat-up nose and a heart of gold.

The walls were filled with framed pictures and signed jerseys of hockey stars. Above the bar, a pair of hockey sticks once used by Wayne Gretzky hung like crossed sabers. You got pizza — the spinach was unbelievable — on the first floor. The bar was upstairs. It was a hell of a lot of fun, Morrissey said: “You gotta go sometime.”

So, on a Friday night in September 1997, Stephanie took a corner stool next to Morrissey’s at the bar. Jack had arranged for his Boston buddy to show up. But someone else did, too.

He strolled in with some other folks fresh from a party, spotted Morrissey and walked over. He had auburn hair, hazel eyes, a baseball cap and an air about him.

His name was Pat Dunn. He was 35. He and Jack were pals. “Two Irish guys” who loved to gab, Morrissey said later. One from Boston, the other from north Jersey. Jack was a cop. Pat’s father was a cop. Jack’s father and brother were Navy men. So was Pat.

Pat was, in fact, an officer; a Naval Academy man, Class of ’85. He wore a beautiful sapphire academy ring, and he was on his way up. He had just come off an overseas tour and was stationed at the Pentagon, which was all right. But what Pat Dunn lovedmore than anything in the world was being at sea. Nothing on land beat it. Nothing.

None of this was known to Stephanie Ross that night in the crowded Penalty Box. Surrounded by sports memorabilia and blaring TVs, she studied this friend of Jack’s in the baseball cap who talked and talked and talked. “He was only there about 10 minutes,” she recalled, “but he talked the entire time.”

Morrissey cunningly excused himself to go to the restroom. Pat went on. Jokes, tales, blather. He was confident and comfortable. Stephanie listened. Then he had to run. He was going to a football game the next day. He wrote his home number on the back of his business card. “Call me sometime and we’ll go to a Navy game,” he told her.

“Okay,” she said. “Cool.”

The next day, Stephanie called Morrissey to thank him. Last night had been fun, she said. His Boston friend was okay. But, uh, what could Jack tell her about this guy Pat? The Navy guy.

Stephanie knew almost nothing about the Navy. Pat’s card had the abbreviation “Lcdr” before his name. What did that mean? Someone at work later clued her in that that was his rank, lieutenant commander. She took some ribbing and realized she had some homework to do.

She let a few days go by. Then she e-mailed Pat and invited him to a block party at the apartment complex the next weekend. “I don’t know if you remember me,” she wrote. “I’m Jack’s friend. I met you at the bar on Friday. I really enjoyed the conversation that we had.”

Pat accepted, showed up, and they had a great time. They got together again, and again. Within weeks, she was certain: Sooner or later, somehow or other, Pat would be her husband. He was funny and wry and could make you feel like you were the only person on Earth. And in his Navy uniform, he looked like the grandest man in the world.

Stephanie telephoned her mother: “Mom,” she said. “This is it. This is the right person.”

Building a Future

There was one problem. Pat wanted no part of marriage. No, ma’am. Not Pat Dunn. Ships and the sea were his loves, the sirens that beckoned him. There would be no fair maiden’s hand for him. He was betrothed to the Navy. Or so he thought.

As time passed, Pat and Stephanie grew closer. They were together almost constantly. Glittering Navy gatherings. Friday nights at the Penalty Box, later renamed Bugsy’s.

They’d eat pizza, drink some beers, yak. It was a great time in their lives. Pat still grumbled that he would never get married. But Jack Morrissey told him he was nuts: Stephanie was a jewel, and Pat knew it. Cripes, this could be Pat’s last chance, Jack toldhim: Don’t blow it.

A year passed. Pat continued at his Pentagon job, Stephanie at Marymount University, where she worked in the admissions office. Then one day after they had had lunch at a diner near the Pentagon and she was driving him back to work, he blurted: “I got orders for Italy.”

She almost crashed the car. “What?” she said. They pulled into a Pentagon parking lot. Pat said he’d actually gotten the orders some time earlier. “I haven’t known how to tell you,” he said.

“Well, we need to make some decisions, I guess,” she said. Pat said he didn’t have to leave for several more months.

“I will follow you around this world,” she said. But not without a commitment. “I love you and I think the world of you. I don’t want to lose you. But if this isn’t right for you, tell me now. Don’t keep me hanging on.”

Pat looked rueful. “Now I’ve upset you,” he said.

But he kept her hanging on.

By the summer of 1999, Pat was about to leave for training before his deployment. Stephanie had waited enough. On June 16, she called him at work: “If you want me to go with you, we need to figure this out,” she said. Okay, he said. Call the jeweler. Make an appointment. “We’ll go there and find something for you.”

The next day, they went to a jeweler and picked out a ring. He would give it to her formally later. They decided to do it over dinner at the Old Ebbitt Grill in downtown Washington, a few blocks from the White House.

They took the Metro from his apartment. They were quiet and nervous as they took their seats in the restaurant. “Do you want your present before dinner or after dinner?” he asked her. “That’s up to you,” she said.

He reached into his pocket and took out the ring. Then he leaned across the table and whispered in her ear: Would she marry him? “Yes,” she replied, then joked, “Why didn’t you get on one knee?”

A wave of relief swept over them. They dined, talked. She showed the ring to the bartender. They called their parents from outside the restaurant. They decided to go to Bugsy’s. There, Watson, the ex-hockey player who owned the bar, said to Pat: “Finally. I thought you’d never ask her.”

Waiting and Worrying

They set the date for Oct. 23. Pat deployed to Europe early, but he came back two weeks before the wedding. They were married at a Navy chapel on Nebraska Avenue in Northwest Washington. Five days later, he went back to Europe. A week and a half after that, she joined him.

They wound up in an Italian port on the Gulf of Gaeta, where the USS LaSalle, a command ship on which Pat was the executive officer, was based.

He called that their honeymoon. She pointed out that it would have been if he had been around. He was very busy.

“He worked from 4 o’clock in the morning to 7 or 8 at night,” she said. “He was exhausted the entire time he was over there. But in order to be successful, that’s what he needed to do. And I knew that. Before we were married, he asked me if I was willing to accept that. I said yes.”

“Did I understand what it would be like as a naval officer’s wife?” she said. “Did I understand that there would be deployments? Did I understand that there would be responsibilities?”

She understood.

Thus did they spend 14 months in Italy, both in service to the Navy. Much later, after Pat was gone, Stephanie would recall how she could tell when the LaSalle was headed out to sea: From their apartment, she could hear three blasts of the ship’s hornas it left the berth, and one more as it headed into the gulf.

At the sounds, Stephanie would hurry to the roof of their apartment building with a big blue and gold Naval Academy flag. And as the vessel passed, she would grip the flag by its staff and wave farewell. Then, like thousands of sailors’ wives before her, shewould wait.

As she passed the time with her cat, which had traveled overseas with them, she had a tendency to fret. She had heard a story once about an officer whose legs had been severed when one of his ship’s mooring lines had snapped.

Pat supervised mooring. What if that ever happened to him? “Of all the things that he did, I was always worried about those stupid lines,” she said. He would laugh: “You worry too much. Nothing’s going to happen.”

Family Ties

They came back from Italy in December 2000. Pat had a big new job at the Pentagon, on the concepts and strategy branch of the chief of naval operations’ staff.

They moved into a rented town house in Springfield, and Stephanie got a job in the marketing department of Greenspring Village, a nearby retirement community.

They started to discuss children. Pat wanted six. They settled on three. Life quieted down. They took a real vacation at a rural cottage her parents owned in Ohio. Pat loved it. After the frenetic months abroad, they had time to get reacquainted.

They went to Bugsy’s, where the same folks still showed up on Friday nights.

Seven months later, on July 4, she firmly believes, she became pregnant. She had had some surgery earlier and wondered whether she would be able to conceive.

That she did so quickly was a mysterious blessing, she now believes: “by the grace of God.” She bought a home pregnancy test. When she told Pat about the baby, he laughed: “Now you’re going to be up all night.”

They took another vacation to the cottage in August. Her whole family was around. It was the start of a great tradition. “Now that we were stateside, we were going to get my family together every August,” she said. “This was the first annual Ross get-together.”

It was the last time her family would see Pat alive.

On September 11, Pat rose for work as usual, kissed Stephanie goodbye, and for the first time kissed her stomach, too. After she got to work, he called and told her about the attacks on the World Trade Center. Then the Pentagon was hit.

“No!” she screamed when she heard about it.

She said she sensed instantly that he was dead. “It was like almost part of me left,” she would say later. “It’s like my body knew, and I don’t know how to describe it. But part of me left with him. I knew right away — my life had just changed.”

Mourning and Preparing

The following days and weeks were a numbing blur. Her parents, Jim and Martha Ross, rushed to Virginia from their home in North Carolina. Pat’s body was recovered and his academy ring returned to Stephanie.

He was laid to rest in Arlington National on September 27, within sight of the charred hole in the Pentagon.

Stephanie had okay days and dreadful days; her “miss Patrick days,” she called them.

Exactly a month after the attack, she attended the memorial service for the Pentagon victims, presided over by President Bush, at the Pentagon.

That night, Bugsy’s owner, Bryan Watson, hosted a celebration of Pat’s life at the bar. They had a bagpiper outside, pictures of Pat and Stephanie on the walls upstairs, and plenty of spinach pizza.

Then came the holidays, a time she dreaded. Thanksgiving arrived. The Saturday after, her mother came to her room in the morning and told her that her father had collapsed in the kitchen. He couldn’t move and appeared to have had a stroke. The paramedics were on the way.

When they arrived, Stephanie was a wreck. Her mother told the paramedics: Her husband was killed in the Pentagon, and she’s pregnant with her first child. One medic sat her down on her living room stairs: “You’ve got to be strong,” he said.

“I’m tired of being strong,” she cried.

After Christmas, she went back to work. All the while, her baby, due Good Friday, made its presence increasingly apparent. In January, she learned she was having a girl. She decided to name the baby after the town where she and her husband met, a town he loved. She’d be Allie, for short. Her middle name would be for her father.

Stephanie thought about many things. Would the baby be hurt by her emotional trauma? She sensed not. “I’m going to be okay,” she told her mother one day in the kitchen. “This baby’s going to be okay.”

How would the child cope with the murderous world into which she would be born?

“I think Allie’s going to make the best of whatever she’s given,” she said. “I can’t control what happens in the world. The world’s never going to be perfect. It’s up to me and the people that surround Allie to teach her that the world’s going to be okay.”

And what would she tell her daughter about her father?

“I’ll tell her that he was serving his country, and that unfortunately there are bitter people in this world that are very angry towards Americans and they happened to take a plane and fly it into Daddy’s building,” she said. “I’ll tell her whatever she wantsto know. If I don’t have the answers, I’ll get the answers.”

But she’d have to do it all by herself.

“That’s what I’m scared about,” she said. “That’s what makes me the saddest.”

Having a Baby

Friday morning, Stephanie’s Navy doctor, Kim Wever, telephoned: “How’d you like to have a baby today?” Stephanie’s blood pressure was rising, Wever said, and lab test results suggested that the best thing was to induce labor right away.

Stephanie packed her things and drove her parents — her father now recovered — in her big sport-utility vehicle with Pat’s old Naval Academy license plates, “DUNN85,” to the hospital. She donned a blue smock and crawled into a bed under a green blanket, and while a monitor broadcast the swooshing gallop of the baby’s heartbeat, the doctor chemically triggered labor.

“I feel great,” Stephanie said shortly after noon. “I’m ready to do this.”

The hours slipped by. The afternoon faded. Stephanie’s brother, Scott, arrived from Pittsburgh. Darkness fell on a beautiful late-winter evening.

It was Friday night.

The kind of night they might have been at Bugsy’s.

Military’s aid and comfort ease 9/11 survivors’ burden

Tue Aug 20, 8:17 AM ET

USA TODAY

In the months just before her daughter Alexandria was born, Stephanie Dunn stopped coming to Arlington National Cemetery. She didn’t want people to see a pregnant woman kiss a headstone.

But now she comes often to section 64, a quiet corner overlooking the side of the Pentagon where American Airlines Flight 77 crashed. On a recent hot day, she propped Allie, now 5 months old, on the parched grass atop Navy Commander Patrick Dunn’s grave. The infant’s tiny hand grabbed the smooth marble stone.

”That’s Daddy,” cooed her mother. She kissed her husband’s headstone and strapped her daughter into the stroller Pat picked out a week before he died. It’s blue and gold, the Naval Academy colors.

Walking amid dozens of markers reading ”Sept. 11, 2001,” Dunn is among friends. ”He came to our engagement party,” she says of one. ”We were at his house for dinner,” she says, pointing to another.

Almost half of the 125 people who died inside the Pentagon, and three Navy veterans among the 59 killed aboard the hijacked jet, lie here. They remain in death, as in life, part of the military family. So are those they left behind. Nearly a year after the terrorist attacks, the military’s fiercely held tradition of taking care of its own has proved a powerful salve for the wounds of Sept. 11.

Many of the families of those killed at the World Trade Center in New York and on United Airlines Flight 93 near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, were pretty much on their own. But Pentagon families were embraced by a longstanding support system. It meant free burial plots, counseling, help in applying for benefits, running errands and more.

”The military community is much better prepared to deal with the kind of losses experienced on 9/11,” says Peter Feaver, a Duke University political scientist who studies civilian-military relations. ”It would be a mistake to think that the losses do not hurt as much, but we would expect a military community to recover more quickly than a civilian community.”

That expectation, oddly, has fed resentment among some Pentagon families. Many say the news media spotlight has focused too narrowly on New York. None here dispute the differences. A staggering 2,823 died in New York, 184 here. The World Trade Center was destroyed. The Pentagon is nearly whole again; workers started moving back into the rebuilt section last week.

As the nation prepares to mark the anniversary of the attacks, much of the attention will again be on the yawning chasm in New York. And some at the Pentagon can’t help thinking America has relegated their loss to a sideshow, perhaps because they are seen as a more ”legitimate target” than the twin towers. Never mind that more civilians, 70, died in the Pentagon than uniformed military, 55.

There’s an unspoken perception among civilians that ”the military expect to die,” says Teri Maude, whose husband, Army Lieutenant General Timothy Maude, 53, was the highest-ranking officer killed at the Pentagon. ”But that’s not true.”

Especially not for people sitting at a desk in the fortresslike Pentagon.

‘Just like in the movies’

Commander Marty Martin appeared at Stephanie Dunn’s Springfield, Virginia, townhouse at 3 a.m. Sept. 12. ”There was a knock on the door, just like in the movies,” she recalls. Accompanied by a chaplain and another officer, Martin introduced himself as her casualty assistance officer and told her what she already knew: Pat, 39, was among the Pentagon missing.

In the weeks that followed, Martin was with Dunn up to 12 hours a day. When Pat’s remains were identified, Martin broke the news. He claimed Pat’s mangled uniform when Dunn couldn’t bear to see it. He planned and, as commander of the Navy’s ceremonial guard, conducted Pat’s funeral in view of the charred Pentagon. He explained benefits and filled out forms. When Allie was born, when Dunn’s father had a stroke, when she needed groceries, Martin was there.

”My husband knew the Navy would take care of me. ‘Once a shipmate, always a shipmate,’ ” says Dunn, 32, one of eight Pentagon widows who had babies after Sept. 11. ”It makes me feel bad that (civilians) don’t have the resources I have.”

Including financial resources. Like all September 11 survivors, Pentagon families are eligible for the federal victims compensation fund, Social Security, Red Cross donations and money from other charities. Survivors of servicemembers killed on active duty are also entitled to at least $250,000 in life insurance, 55% of a spouse’s pension until the survivor remarries, a $6,000 death payment for immediate expenses, burial costs, health care coverage and other benefits.

For Martin, 41, it is a ”lifelong assignment” to ”take care of the family that’s left behind.” And it’s one that has evolved from duty to friendship. He invited Dunn to his wedding last week. She invited him to Allie’s baptism on Pat’s old ship, the carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt, in December.

Kevin Shaeffer, 30, sat next to Pat Dunn in the Navy Command Center. Shaeffer was the only one of 30 people in that office to survive. He also says ”my Navy family” was ”absolutely vital.” Officials gave his wife, Blanca, a Navy lieutenant like him, months of paid leave to be at his side at Washington Hospital Center’s burn unit. A Navy official was always in the waiting room ”as a shoulder to cry on,” he says.

The young officer’s injuries were among the worst of the 140 people wounded in the attack. He suffered severe burns on 42% of his body, lost most of the skin on his arms, hands and back, and inhaled jet fuel that damaged his lungs. His heart stopped twice

In what he calls one of many miracles — the first was his survival and escape — Shaeffer turned a corner the next day and began a slow recovery. He spent three months in the hospital and endured 17 surgeries, the last in June.

Shaeffer will wear gray pressure gloves and shirts to reduce scarring until January. His right arm is numbed by nerve damage. He is in constant pain and has trouble breathing at night. Yet he’s over the worst physical hurdles. He knows because his nightmares started last month. ”I’m onto the next thing that needs healing,” says Shaeffer, who is mulling his next career, possibly in public service. ”I expect it to get harder before it gets easier.”

Paul Gonzales’ nightmares started immediately after Sept. 11. They’ve subsided, but the guilt about surviving has not. The Defense Intelligence Agency lost seven people that day. Three worked for Gonzales, the civilian deputy comptroller.

”It doesn’t make sense — two young mothers and a man a year from retiring. That’s what keeps you up at night,” says Gonzales, 47, a retired Navy Commander who was hospitalized with lung damage. That he received his agency’s highest award for leading five people to safety doesn’t ease the pain.

But he and his co-workers are finding ways to cope. Every desk in the agency’s offices is now equipped with a flashlight and emergency smoke hood. Also on hand: fire axes, smoke blankets and fire extinguishers.

Not every Pentagon office has such safety gear; that’s up to each supervisor. But the Army’s Operation Solace, a stress management program set up for Pentagon employees within days of the attack, is available to all.

Using ”therapy by walking around,” nearly 100 counselors have gone door to door, desk to desk, to talk to every employee, military and civilian. Many reported sleep and eating problems and sensitivity to loud noises.

The program offers individual counseling, support groups and other mental health services. In a culture that teaches its own to ”soldier on” in adversity and traditionally rejected therapy as a sign of weakness, many have accepted.

Among them was Tony Rose, a gruff Army sergeant major with 31 years of soldiering. Rose has been in therapy since October. He went back into the burning building five times to rescue survivors — heroism that earned him the Soldier’s Medal for bravery. He still has nightmares about the body parts he later helped recover.

”It’s part of our life pattern to respond to emergencies,” says Rose, 48. ”It’s our military training that you just do what you have to do.”

Despite such lingering difficulties, Army Lt. Col. Charles Milliken, Operation Solace’s director, says the military community has proved resilient. ”We’ve seen remarkably little major psychiatric illness” compared with workers in klahoma City after the 1995 bombing that killed 168 people — fewer than died at the Pentagon.

War provided ‘reason’

The war on terrorism helped, providing a mission and a distraction. ”There was a reason beyond themselves that made it important to come to work,” Milliken says.

Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld set the tone the evening of Sept. 11. Standing at a podium in the still-burning building, Rumsfeld declared: ”The Pentagon’s functioning. It will be in business tomorrow.” And it was. Nearly half of the Pentagon’s 23,000 workers showed up for work Sept. 12.

But as troops headed for Afghanistan ( news – web sites) in late September, there was a gnawing feeling among those who survived the war’s opening that their suffering was being overlooked. It wasn’t overt or intended, but people took note of the slights:

* The daughter of a Navy captain who was killed wrote to The Washington Post that the National Memorial Day Concert at the Capitol focused on the twin towers and paid ”token” attention to the attack across the Potomac River.

* Meg Falk, who coordinates support for Pentagon survivors, was dismayed by commemorative books that had ”hundreds of pages with pictures of New York and just one or two of the Pentagon.”

* America: A Tribute to Heroes, the star-studded telethon that aired Sept. 21, had one celebrity, Julia Roberts, talking about the Pentagon attack. ”That doesn’t go unnoticed by any of the survivors,” Shaeffer says. ”It’s important that no one forget what happened at the Pentagon. To my wife and me, our tragedy is equal to the tragedy in New York.”

Other Pentagon families were happy to remain in the shadows. ”The focus on the World Trade Center has given them a chance to recover at their own pace and not under the spotlight,” says Maj. Todd Leavitt, an Army psychiatrist. Some bonded with their New York and Pennsylvania counterparts. In June, Dunn went to the Bronx Botanical Gardens to meet 100 other women who had given birth to fatherless babies. ”We all became one family that day,” she says. ”It’s not ‘My story’s better than yours.’ It was ‘How are you doing?’

And there was support. The drab Pentagon hallways soon sprouted hundreds of colorful posters drawn by schoolchildren from across the nation. Families were inundated with letters and e-mails. Though unconscious at the time, Gonzales says he still appreciates that first lady Laura Bush visited his bedside at Walter Reed Army Medical Center on September 12.

But Maude says others felt ”great frustration” at the constant media focus on New York. ”There was nothing about the heroes at the Pentagon,” she says. ”It was like, ‘Don’t they know something happened in D.C. as well?’

Feaver says news coverage may have differed because ”the military do promise to put their lives on the line to defend the country in a way that Wall Street brokers and cafeteria workers do not. That changes the nature of the trauma and shock which their deaths inflict” on the public.

But not on their families. ”I still ask how am I going to do this on my own,” says Dunn, looking at Allie amid a dozen red, white and blue baby quilts sent by strangers. ”It doesn’t matter how many caves we blow up, it’s never going to bring my husband back.”

Stephanie Ross Dunn: Widow of Pentagon victim

Wednesday, September 11, 2002

Alexandria Patricia Dunn was born March 15, 2002. She was named for the Washington suburb in which her parents met and for the father who died when a hijacked airplane slammed into his office at the Pentagon on September 11, 2001.

The baby’s arrival allowed Stephanie Ross Dunn, who lost her husband, Navy Cmdr. Patrick Dunn, to do something she hadn’t been able to manage since December: Visit his grave in Arlington National Cemetery, on a spot overlooking the place where he died.

“I had a hard time being pregnant and visiting a gravesite of my husband,” Dunn said. “I didn’t want people to see a pregnant woman there. I didn’t want people to feel sorry for me. I still don’t want people to feel sorry for me.”

Now, she says, “Allie” feels at home next to the small, white stone in the national cemetery.

“It’s always important for me to let her touch the headstone. Now she tries to eat it. She tries to put it in her mouth,” Dunn said. “She does her cooing and talking to him. It’s really kind of neat.”

Dunn, 32, raised in Upper St. Clair and Mt. Lebanon, has settled into single motherhood by living on a combination of her husband’s pension, Social Security, and Red Cross stipends that are now three months overdue. She put aside some insurance money in hopes of someday buying a house for herself and Allie.

The telephone at her suburban Washington, D.C., home answers as “the Dunn family” and she plans to return to work at some point. In the months preceding Allie’s birth, Stephanie had left her job at a retirement community.

Stephanie is not the only Pentagon widow who has given birth since Sept. 11. She became close to another of these women, who had a son two months after Allie.

“They’re going to get married,” she laughed. “We’ve saved ourselves the trouble of having them date.”

The sense of humor took a while to return.

In the weeks after 9/11, Dunn was almost paralyzed by the publicity and her grief. She remembers standing in the frozen foods aisle of a grocery store, weeping quietly at the sight of the single-serving dinners she was now buying.

“Now it’s part of life. Now it’s become normal for me to be shopping for one. Plus formula, of course,” she said.

She has done the usual round of interviews. The Washington Post covered Allie’s birth on its front page. She will do a few television shows, including a live broadcast from the Pentagon on the anniversary, but plans to draw back from public life after the anniversary.

“I want Allie to grow up as Allie, and not the Pentagon Girl,” she said.

Dunn has watched the progress of the American military and the Bush administration. She thinks both are doing superbly.

“In my heart I know the armed forces are going to take care of us and there’s nothing I can do by worrying about it. I think the president’s doing the best he can and doing a great job,” she said. “I don’t think it’s equivalent to a huge war like World War II or anything like that, but we all know in our minds that it’s going to be taken care of.

“The world’s going to be a better place. But I don’t know when that’s going to be.”

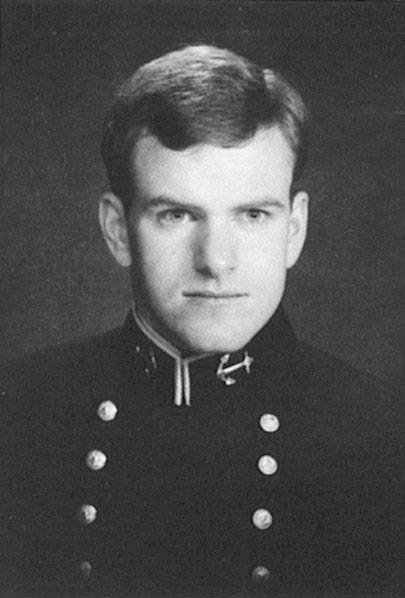

Patrick Dunn as Midshipman United States Naval Academy

NOTE: Commander Dunn was laid to rest in Section 64 of Arlington National Cemetery, in the shadows of the Pentagon.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard