U.S. Department of Defense

Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs)

News Release

IMMEDIATE RELEASE No. 219-09

April 05, 2009

DoD Identifies Air Force Casualty

The Department of Defense announced today the death of an airman who was supporting Operation Enduring Freedom.

Technical Sergeant Phillip A Myers, 30, of Hopewell Virginia, died April 4, 2009, near Helmand province, Afghanistan of wounds suffered from an improvised explosive device. He was assigned to the 48th Civil Engineer Squadron, Royal Air Force Lakenheath, United Kingdom.

For further information related to this release, please contact the RAF Lakenheath UK Public Affairs office at 44-1638-52-2151.

5 April 2009:

Courtesy of CNN

DOVER AIR FORCE BASE, Delaware — His name was Phillip A. Myers. A Staff Sergeant in the U.S. Air Force, he was killed in a roadside bombing in Afghanistan on Saturday.

The body of Phillip Myers, 30, arrived at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware on Sunday.

The return of his body to the United States aboard a charter aircraft Sunday

marked a solemn moment that has been repeated more than 5,000 times at Dover Air

Force Base in Delaware since the start of the war in Afghanistan in late 2001.

Much of this night was like so many of the others: The well-practiced and crisp movement of the carry team silently transferring the body from the plane to the truck that would transport it to the base mortuary and the presence of Myers’ family, quietly watching every step and order, ensured dignity and respect for the fallen in an atmosphere that does not lend itself to peace and quiet.

This night, however, was not like the other nights. Watching all of this were about 40 journalists allowed to cover the return of Myers’ remains. It was the first time in almost 20 years the return of a fallen U.S. service member was able to be recorded by the media.

Myers’ widow was the first to be asked by the military, under a new policy by Defense Secretary Robert Gates, if she wished to have news media at Dover Air Force Base for her husband’s final return home. Her decision to do so was historical and allowed the public to see a side of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq the country has not yet seen.

The only noise on the flight line was the perpetual whine of the Atlas Air 747’s power generator. This was the plane that had brought Myers and another fallen soldier back to the United States. The media were not allowed to cover the other soldier’s transfer and were not given his name or the circumstances of his death, because the family had not granted permission.

On the flight line, journalists were asked not to speak, use camera flashes or make undue movement while watching the transfer.

With cameras rolling, an eight-member carry team wearing battle-dress uniforms and white gloves stood by the flag-draped transfer case carrying Myers, as the Chaplain, Major Klabens Noel, said a prayer.

The team slowly moved the transfer case from the aircraft onto the loader. With a jolt, the quiet of the night was shattered as a diesel engine was started to lower the loader toward the ground and then was shut off.

Bathed in light from the giant floodlights along the flight line, the team hoisted the transfer case and carried it to a waiting panel truck.

As the transfer case was secured, the carry team saluted, the doors of the truck were slowly closed and then driven under police escort to the base mortuary.

Seven family members watched the truck until it was out of sight, one man among them crying into a tissue.

Myers was from Hopewell, Virginia, and died Saturday of wounds suffered in a roadside bombing, the Air Force said.

He was assigned to the 48th Civil Engineer Squadron, with the Royal Air Force Lakenheath, UK, and in March 2008 received the Bronze Star for valor. He was 30 years old.

The ban on media coverage of returning war dead was implemented by President George Bush in 1991 and the policy has been the subject of much debate since. Some called it censorship; others said it allowed privacy and respect for the families during a very difficult time.

An exception on the ban by President Bill Clinton in 2000 allowed coverage of the return of sailors killed in the attack on the USS Cole.

Shortly after taking office, President Obama asked Gates to take a look at the policy. In February, Gates reversed it, but with conditions. Family members would be asked if they wanted news media to cover the transfer of their loved one’s body.

Service members’ support groups had mixed opinions on the change. Some welcomed the change to show the human cost of war, and others opposed it.

“We are committed to seeing that America’s fallen heroes are received back to their loved ones and their country with the honor, respect and recognition that they and their families have earned,” Gates said after his decision.

“The overriding principle is that decisions about media coverage should be made by those most affected: the families,” he said.

By Reed Williams

Courtesy of the Richmond Times-Dispatch

Published: April 7, 2009

The mother of an Air Force sergeant whose body was returned from war Sunday said she is glad news media coverage will allow Americans to see how respectfully the military honors its dead.

Staff Sergeant Phillip Myers of Hopewell died Saturday from an explosion near Helmand province in Afghanistan. With his family’s permission, the military allowed the media to cover the arrival at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware, the first public return since the Pentagon lifted its 18-year ban on coverage of returning war dead.

Myers’ mother, Treasa Hamilton of Polkton, North Carolina, said yesterday that such media coverage will allow Americans to visualize better what is happening overseas.

“They hear 30 people killed in Iraq — they’ve gotten used to it,” Hamilton said. “This brings it back to the forefront. They can actually see the soldiers coming home.”

Myers’ wife, Aimee Myers, permitted the coverage because her husband believed in his role overseas and would want the public to witness the dignity with which the war dead are returned home, Hamilton said. Aimee Myers was unavailable for comment.

“It was all very well done,” Hamilton said of Sunday evening’s ceremony in Dover. “It was very respectful.”

Myers, a 30-year-old father of two children, had been scheduled to leave Afghanistan in mid-May and would have been moved to Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, Hamilton said.

She said her son told her last week that he wanted to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery if he were killed, a request he had made previously. She said yesterday that Myers will be buried there but that a date had not been set.

Myers was assigned to the 48th Civil Engineer Squadron with the Royal Air Force in Lankenheath, England, a base that is used by the U.S. Air Force.

He was a member of an explosive ordnance disposal team, and part of his job was to disarm improvised explosive devices, his mother said. She said she didn’t know whether he had been trying to disarm the IED that killed him.

“It took a lot of courage and nerves of steel, because he was constantly handling explosives and on the lookout for explosives,” Hamilton said.

She said Myers had served in Iraq and Kuwait, as well as in Afghanistan, and that he had conducted bomb sweeps in Washington to protect then-President George W. Bush.

Myers attended Hopewell High School and joined the Air Force in 1999, Hamilton said. Relatives described him as a dedicated military man who believed he was protecting his friends, his family and his country.

He was especially protective of his children and would make sure his daughter, 5-year-old Dakotah, wouldn’t watch TV shows with bad language, family members said.

His 2-year-old son, Kaiden, likes to build things with Legos just as his father did when he was little, Hamilton said. Once, Kaiden built a pretend gun. “He said, ‘Now I have a gun like Daddy for the bad guys,'” Hamilton said.

A ceremony to honor Myers is planned for Thursday in England, Hamilton said. Hopewell Mayor Brenda S. Pelham said the city also would like to have a service for Myers if his family wishes it.

“My heart just hurts every time I see a young person” killed overseas, Pelham said.

Myers is survived by his wife and children, as well as his mother, father, brother and stepfather.

Media covers return of fallen airman

By Beth Miller

Courtesy of The (Wilmington, Delaware) News Journal via Gannett News Service

Tuesday April 7, 2009

DOVER, Delaware — The service of Air Force Staff Sergeant Phillip A. Myers, 30, of Hopewell, Virginia, was not finished when he died Saturday in Afghanistan of injuries suffered from an improvised explosive device.

Late Sunday night, the arrival of Myers’ body at Dover Air Force Base in a flag-draped transfer case became a powerful reminder to his nation and the world of the sacrifices made by members of the armed forces and the high cost of war.

His return also marked an early watershed in the administration of President Barack Obama, a nod in favor of transparency and away from secrecy favored by prior administrations.

Thousands of fallen troops have returned to the United States through the military’s primary mortuary at Dover Air Force Base. Their flights are met by an honor guard, by military officers, by a chaplain and other dignitaries. Their remains are afforded the highest respect and precision as they are processed for return to their final destination.

But until Sunday night, no news coverage of the returns had been permitted since 1991, when President George H.W. Bush and then-Defense Secretary Dick Cheney banned media coverage.

Privacy was cited as the primary reason.

That changed as Myers’ flag-draped transfer case was escorted by an eight-member carry team with crisp, solemn precision to a waiting van from the jet that had carried it from Ramstein, Germany. On Sunday, a few more than two dozen media members quietly snapped pictures, scribbled notes or trained video cameras at the procession shortly after the plane landed at 10:30 p.m.

The casket of an Army soldier was taken down first. That soldier’s family was not asked for permission for media viewing because of time constraints.

“My heart is broken for this family,” said Judy Campbell, chair of Gold Star Families of Delaware, which honors those who have lost a family member in military service. “Their life is changed forever. I hope that having this picture of their loved one returning, that in the years to come it will give them some peace … some comfort.”

For almost 20 years, that hadn’t been possible. Glimpses of the returns were made available only when the Pentagon released hundreds of its own photos after a 2005 Freedom of Information Act lawsuit filed by University of Delaware professor and former CNN correspondent Ralph Begleiter.

The media ban was lifted last month after Obama ordered a review of the policy. After the review, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates decided coverage would be permitted — but only with the family’s consent.

Obama opened the door to reconsidering the policy in his first prime-time news conference as president in early February. He said he had not decided on the policy and wouldn’t until “I have evaluated that review and understand all the implications involved.”

Vice President Joe Biden in 2004 had urged a change to the policy, when the then-senator told CNN: “This is the last long ride home. These young men and women are heroes. And the idea that they’re essentially snuck back into the country under the cover of night so no one can see that their casket has arrived, I just think is wrong.”

Almost all of the 4,266 casualties in Iraq and the 668 casualties in Afghanistan through the end of March have come through Dover’s mortuary, military officials said earlier this year.

Dover and Pentagon officials could not provide the total number of transfers that have come through Dover, but Air Force spokesman Vince King said in February that 3,867 had come through Dover between May 2004 and May 2008.

Families and military members have been divided on whether the policy should have been changed.

Some agreed with Biden that acknowledging and honoring the fallen troops is an important part of the nation’s ability to better understand the cost of war and the sacrifices made by service members and their families.

Others were concerned that such coverage would be used to advance a political anti-war agenda — as some did in the Vietnam War years — or turn a somber occasion into a “media circus.”

As the window was opened Sunday night to readmit the public to the returns, the procedures put in place by the military were tight and designed to allow the procession to be recorded without allowing media to interfere.

About 30 media members boarded a bus in the Blue Hen Corporate Center at 9 p.m. for transport to the nearby base, then briefed and taken to a restricted area from which they would observe and record.

Each representative signed a set of rules that included a prohibition on taking any images of family members who might be on hand.

No live filming was allowed, nor were “stand-ups,” in which a commentator speaks into a camera as the action unfolds in the backdrop.

The military rules advised media members that “there will be no unnecessary noise or movement during the transfer. Movement required to perform duties should be conducted in a slow and deliberate manner in an effort to not distract from the event.”

Major Paul Villagran assumed a new job as director of public affairs for the Air Force Mortuary Affairs Operations Center a week ago to prepare for the change in policy, which was to take effect Monday. By Sunday, more than 80 members of the media had registered to be notified of a permitted return.

Villagran said all was devised to protect the family’s privacy and preserve the honor and dignity of the return.

“There is no amount of effort we wouldn’t put forward to provide that care and support,” Villagran said Saturday.

Myers’ widow was the first to be asked about media coverage and granted permission. She was flown into Dover on Sunday night from the RAF base in Lakenheath, England, where Myers had been assigned to the 48th Civil Engineer Squadron.

Myers died Saturday near Helmand province. He was awarded the Bronze Star at a March 19, 2008, ceremony at Lakenheath. He also had won the Air Force-level 2008 Major General Eugene A. Lupia Awards military technician category for significant achievements.

Other family members drove to Dover on Sunday from Virginia. The military paid for all family travel expenses to Dover.

At precisely 11 p.m., a dark blue shuttle bus carrying family members arrived, and an eight-member carry team, all wearing white gloves, marched to the aircraft. They slowly mounted the long stairs to the cargo bay and walked to the spot where a K-loader was positioned with Myers’ transfer case.

The senior officer on the team, Major General Del Eulberg, the Air Force’s civil engineer, was joined by Colonel Dave Horton and Major Klavens Noel, a Chaplain, at the cargo bay door. The chaplain offered a brief prayer.

The team then raised the case and positioned it at the end of the K-loader, which descended slowly to the tarmac. The team then slowly bore the case to a white panel truck and loaded it inside.

The van then was driven off with an escort to the mortuary area. The ceremony was marked by silence, except for two orders from an officer.

Campbell, the chair of the Gold Star Families, said she believes that Sunday’s recognition of the significance of Myers’ sacrifice is important.

“I really do believe, when people know that other people care and remember, it does bring them some comfort,” she said. “Their loss will always be there, but it’s always comforting to know that others are not forgetting the sacrifice.”

Begleiter, who has said he launched his FOIA effort with the National Security Archive in 2004 to restore the return ceremonies at Dover to a rightful place of honor, had this to say Sunday: “This is an important victory for the American people to be able to honor their returning servicemen and women who have made the ultimate sacrifice.”

On March 19, 2008, Air Force Lieutenant General Robert D. Bishop Jr. presented Staff Sergeant Phillip Myers

with a Bronze Star. Myers, 30, of Hopewell, died Saturday in Afghanistan from wounds suffered from

an improvised explosive device. After receiving permission from family members, Air Force officials planned

to open Dover Air Force Base, Delaware for the media to observe the return of the body of Myers on Sunday night.

NOTE: Staff Sergeant Myer will be buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery at 3 P.M. 27 April 2009.

Members of an Air Force honor guard prepare for the funeral of Air Force Tech Sergeant

Phillip Andrews Myers, Monday, April 27, 2009, at Arlington National Cemetery

An unidentified Air Force Colonel, left, and a Air Force Staff Sergeant salute the flag-draped casket of Air Force

Tech Sergeant Phillip Andrews Myers, Monday, April 27, 2009, during a burial service at Arlington National Cemeter

An Air Force casket team carries the flag-draped casket of Air Force Technical Sergeant Phillip Andrews Myers

Monday, April 27, 2009, during a burial service at Arlington National Cemetery

Air Force Major General Del Eulberg, left, kneels as he presents a folded American flag to Kaiden Myers, the son

of Air Force Technical Sergeant Phillip Andrews Myers, Monday, April 27, 2009, during burial services at Arlington National Cemetery.

Watching from right is Aimee K. Myers, the widow of Technical Sergeant Myers and at left is their daughter Dakotah

Major General Del Eulberg presents the U.S. flag to Treasa Hamilton during the funeral for her son

Technical Sergeant Phillip A. Myers April 27 at Arlington National Cemetery

Eddie Myers places a folded flag in a shadow box following the funeral for his son,

Technical Sergeant Phillip A. Myers, April 27 at Arlington National Cemetery.

Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates walks through Arlington National Cemetery after paying his respects to the family

of Air Force Technical Sergeant Phillip Andrews Myers, Monday, April 27, 2009, during his burial at Arlington National Cemetery

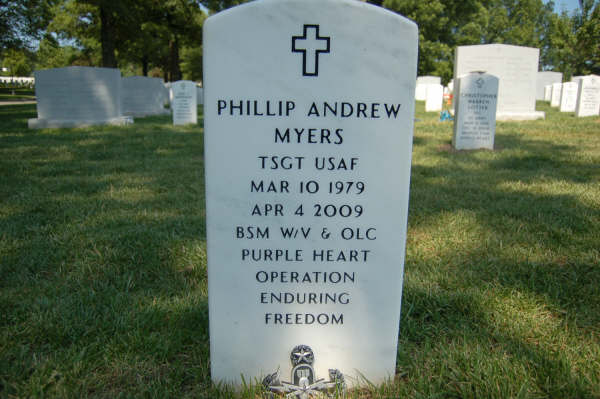

MYERS, PHILLIP ANDREW

- TSGT US AIR FORCE

- DATE OF BIRTH: 03/10/1979

- DATE OF DEATH: 04/04/2009

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 8873

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard