Two TV shows to look at downed pilot

February 20, 2004

Cooper High School graduate Nathan White was killed almost a year ago in Iraq at age 30, but his story lives on in two upcoming television programs.

One will be in Japanese and shown only in Japan. The other will be on CBS Sunday night.

White’s Navy F/A-18C Hornet was shot down April 2 by a Patriot missile during a sortie over Iraq. CBS’ 60 Minutes is airing a segment on friendly fire incidents involving the Patriot missile.

White’s father, Dennis White of Abilene, flew to New York last fall to be interviewed for the program. It is scheduled to air at 6 p.m. Sunday on KTAB-TV (Channel 32, Cox cable Channel 10).

The Japanese program will be more personal. The moment two Japanese television reporters met White aboard the USS Kitty Hawk, they were intrigued.

Not only could the young man from Abilene speak and read Japanese with ease, he also was different from other Navy pilots on board.

“Not a ‘Top Gun’ type,” said Takemori Kataoka, referring to the cocky pilot that Tom Cruise played in the “Top Gun” movie.

“He was so modest and gentle,” Hisashi Tsuya said.

The two journalists, along with two others from the Japan Broadcasting Corp. are in Abilene interviewing White’s family and friends.

The Japanese show is scheduled to air in mid-March to coincide with the one-year anniversary of the beginning of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Kataoka and Tsuya were embedded journalists on the USS Kitty Hawk.

Before coming to Abilene, the film crew was at Arlington National Cemetery, where White is buried; in Provo, Utah, for a memorial service; and in Orlando, Florida, where White’s wife and three children live.

White took two years from his college days at Brigham Young University in Provo to go on a Mormon mission trip to Japan.

While there, he became fluent in Japanese, and fell in love with the culture and a young woman named Akiko, whom he later married.

The two Japanese reporters met White in the ship’s dining hall and quickly struck up a conversation.

“He was the best friend of us on the ship,” Tsuya said.

In October, Tsuya e-mailed Dennis White expressing an interest in coming to Abilene to do a story on his son. In his message, Tsuya referred to White as “the honorable naval pilot, my friend, Nathan.”

Dennis White was so flattered, he quickly offered to assist any way he could.

“I know how we feel about Nathan,” he said. “It’s nice that other people do, too.”

Tsuya said he and Kataoka had been meeting White almost daily in the ship’s dining hall when that suddenly ended.

“We had never seen him again and were really worried about him,” Tsuya said.

The two men were stunned when they learned their friend had been accidentally shot down by a Patriot missile. The memory of Nathan White wouldn’t go away, and the journalists decided they must do a television piece on him.

For the White family, the ongoing coverage of their son’s death is proving to be therapeutic rather than painful.

“This has allowed me to redirect my emotions so I can do something positive,” Dennis White said.

White said he was especially pleased to see a lesson he taught his son as a youngster was apparent to people who barely knew him.

“If you’re good, people will see that,” White had told his son. “And the lesson took.”

7 May 2003:

U.S. Probes Downing of Friendly Jets

WASHINGTON – Pentagon investigators suspect U.S. Patriot anti-missile batteries may have shot down two coalition jets over Iraq because the systems mistook the planes for Iraqi missiles.

Investigations of the incidents — responsible for three of the war’s five airplane shootdown fatalities — are focusing on a system touted by the Army as a reliable missile-killer but one which has been repeatedly plagued by problems hitting its targets.

The father of Navy Lieutenant Nathan White, killed by Patriots on April 2, 2003, said he hopes the probe will lead to improvements that reduce the chance American anti-missile systems will down friendly planes.

“You go through the normal anger, but I also know it’s a war situation,” said Dennis White, a former Air Force pilot who flew C-130 cargo planes during the Vietnam War. “There’ll be some changes, I know, but you’d think you wouldn’t have to put in stuff to protect your own people.”

The U.S. military is investigating three Patriot incidents: the White case; the downing of a British Tornado jet on March 22 that killed both airmen aboard; and two days after the Tornado shootdown, when a U.S. F-16 pilot fired a missile at a Patriot battery, believing the radar had targeted his plane. The pilot’s missile damaged the Patriot radar battery; no one was injured.

Critics have questioned why Patriot programming and firing rules weren’t changed after the British jet was downed.

“I can see pilot error being the cause of one incident, but three pilots can’t all be making the same mistake,” said Victoria Samson, a missile expert at the Center for Defense Information, an independent Washington think tank. Possible pilot errors include straying from designated safe air corridors or failing to turn off electronic equipment that sets off the Patriots.

Pentagon officials say their probes have not determined whether all three incidents were caused by the same problem or whether mistaken identity was to blame. But top officials at U.S. Central Command strongly suspect misidentification.

Jets flying in certain ways can appear to Patriot radar systems as incoming missiles, according to officials from Central Command and the Army, which operates the Patriots. A spokesman for Raytheon Co., which makes Patriot radars and older versions of the missiles, declined comment.

Patriot systems can be set to automatically fire at incoming missiles. When the missiles are set to “semiautomatic” or manual, Patriot operators have just a few seconds to decide whether to fire.

Coalition aircraft have Identify Friend or Foe, or IFF, systems that broadcast an identifying signal. Patriot systems are designed to seek and recognize those signals and not fire on friendly aircraft. But the Patriot system is not designed to look for an IFF signal from a target it identified as a missile, because missiles don’t have IFF transponders.

Shortly before his last mission, White sent an e-mail to his family about the air war over Iraq. He described how pilots must “navigate through a maze of airborne highways that try to deconflict aircraft and of course steer you away from the Army’s Patriot batteries.”

“Obviously it was a concern, or he wouldn’t have mentioned it,” Dennis White said.

Investigators also are looking at possible IFF system problems, at either the aircraft or Patriots end. Other causes could include errors by the pilots, the Patriot crews or both.

Central Command officials say Patriots downed at least 10 of the 17 missiles fired at Kuwait.

The United States fired 22 Patriots during the war, White House budget chief Mitchell Daniels told National Public Radio. That means 15 percent to 20 percent of the Patriots fired shot down the two coalition planes — of a total four shot down during the war — depending on whether one or two of the missiles hit the British jet.

During the 1991 Gulf war the military and Raytheon also claimed high success — up to 80 percent — with earlier versions of the Patriot. Congress’ General Accounting Office (news – web sites) later found Patriots intercepted no more than four of 47 Iraqi Scud missiles, a 9 percent success rate. The Pentagon has spent more than $3 billion improving the Patriots since then.

On April 2 returning to the USS Kitty Hawk after a bombing run over northern Iraq, White flew his F/A-18C Hornet over Karbala, where Army units were fighting their way toward Baghdad. The Patriots that downed White were defending the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division around that Euphrates River city 50 miles south of the Iraqi capital.

Navy officials told his father that White radioed he saw the two missiles launch — a pair of white flashes in his night-vision equipment. White tried to evade them, but in less than 10 seconds they had destroyed his plane, his father said in a telephone interview from his home in Abilene, Texas.

A 30-year-old father of three, White was buried April 24 at Arlington National Cemetery.

“I don’t know much about the Patriot system works, but there had to be an obvious failure,” Dennis White said. “It took the life of someone very dear to us.”

25 April 2003:

Navy Lieutenant Nathan White joined the honored dead lined up in disciplined rows on a northern Virginia hillside Thursday morning, greeted by a cloudless sky and given a farewell by a heartbroken father who remembered gathering him up as a baby 30 years ago and presenting him with his name.

White, a husband and father of three, died April 2, 2003, when the Navy F/A-18C Hornet fighter jet he was piloting was felled from the sky by a Patriot missile in what was determined to be a friendly fire accident. The Abilene, Texas, native was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, the 13th veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom to earn the distinction.

It was a quiet ceremony, with Chaplain Robert Beltran delivering a prayer whose words were all but lost in the brisk breeze. The flag-covered casket was borne more than a mile to the gravesite on a caisson pulled by six horses. A military band with honor guard led the procession while dozens of mourners, including family members, friends and military personnel, brought up the rear.

Four F-18s participated in a flyover – one of them veering off. A seven-member firing party shot off three rounds each in unison, and taps was played. Vice Adm. Gerald Hoewing gave U.S. flags to White’s widow, Akiko, and his father, Dennis, among others.

Dennis White recalled the first time he held his son, the second of eight children, remembering it as a “sacred and special” moment. Many tears had been shed over his son’s death, he said, but the family remained grateful for the good times.

In an interview earlier in the week, White remembered his son as a good but mischievous boy, very intelligent, who once got his hands on the answer sheet to a test being given at school. He taped it, to the benefit of the entire class, to the front of the teacher’s desk, out of the instructor’s line of sight.

“Everyone got a pretty good grade on that one,” he said.

The elder White was an Air Force pilot who flew C-130s during the Vietnam era, and one time his son stood in a spot for hours waiting for the father to fly overhead. Occasionally he brought his son with him on postwar air excursions. Still, he was surprised when the young man decided to skip law school in favor of pilot school.

“He called me and said, ‘You won’t believe what I just did. I joined the Navy. They’re going to accept me into the pilot program,'” White said. “I never had an inkling. I was surprised how well he took to the regimentation.”

In a final e-mail home, White told his family that his job could sometimes be overwhelming and that it “really gets exciting” at night when you “throw in some thunderstorms.”

“When it gets really hard, it’s like they always say: You fall back on your training,” he said. “Redundancy in training prepares you for those nights where your legs are shaking and you know that if you don’t relax and get your refueling probe into the refueling basket, you are going to flame out and lose the jet.

“Life is no different,” he wrote. “Success in any endeavor is brought about by personal preparation and training for those inevitable obstacles of life. Your Sunday school and seminary teachers, scout leaders and priesthood leaders, and yes even your parents, have valuable lessons of life to impart that are all aimed at preparing you for the tough decisions each of you face.”

Wife Akiko White and daughter Courtney stand with other family and friends during the funeral of Navy pilot Lieutenant Nathan White, 30, of Abiline,

Texas, at Arlington National Cemetery April 24, 2003. At far left is White’s brother, Sergeant Josh White (R), who holds Nathan’s sleeping son

Zachary. Nathan White was shot down by a patriot missile in a ‘friendly fire’ incident on April 2, 2003 during operations in Iraq

Akiki Ohata White, wife of Navy pilot Lt. Nathan White, and daughter,

Courtney, place their hands over their hearts during a graveside internment

ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery Thursday, April 24, 2003.

Navy pilot Lieutenant Nathan White of Mesa is laid to rest in at Arlington National Cemetery yesterday. His father, Dennis

Manning White (standing at center), gave the eulogy during the graveside ceremony. Nathan White, whose unit was

based in Japan, was killed by friendly fire April 2, 2003, when his F/A-18C Hornet was shot down by a U.S. Patriot missile over

Iraq. In addition to his father, Nathan White is also by survived his wife, Akiki Ohata White, and their daughter, Courtney.

Wife Akiko White holds the folded flag as daughter Courtney wipes tears during the funeral of Navy pilot Lieutenant

Nathan White, 30, of Texas, at Arlington National Cemetery, April 24, 2003. In addition, his wife and

daughter, White leaves behind son Austin (seated) and Zachary (sleeping), being held by White’s brother, Sergeant Josh White (R).

Wife Akiko White and daughter Courtney touch the folded U.S. flag given to them during the funeral of Navy pilot

Lieutenant Nathan White, 30, of Texas, at Arlington National Cemetery, April 24, 2003. In addition to his wife and

daughter, White leaves behind son Austin (seated) and Zachry (sleeping), who is being held by White’s brother, Sergeant Josh White.

Wife Akiko White holds the folded flag given to her, as daughter

Courtney wipes tears during the funeral of Navy pilot Lieutenant Nathan

White, 30, of Texas, at Arlington National Cemetery, April 24, 2003.

23 April 2003:

Lieutenant Nathan White, a 1991 Cooper High School graduate and Navy fighter pilot who was killed in Iraq, will be buried Thursday with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

The service, which is open to family and friends, will begin at 10 a.m. A memorial service will be held at 4 p.m. Sunday at the Cooper auditorium. The public is invited.

Previous memorial services were held aboard the USS Kitty Hawk and at the Naval Air Facility in Atsugi, Japan. White, 30, was stationed in Japan and flew his F/A-18C Hornet from the deck of the Kitty Hawk, stationed in the Persian Gulf during Operation Iraqi Freedom.

His plane was shot down April 2 by a Patriot missile. A family friend, Dave Liggett, established a Web site in honor of White, www.ltnathanwhitechildrensfund.org.

The site features tributes to White, news articles, memorial services, and information on donating to a fund established for White’s wife and three young children who live in Japan. Accounts have been opened at several banks, with complete information listed on the Web site.

Gordon Warren

2438 Industrial Blvd.

Abilene, TX 79605

PHOENIX, ARIZONA – A Navy pilot killed when his fighter jet was apparently shot down by friendly fire over Iraq was a dreamer who constantly sought out challenges, his sister said Tuesday.

Lieutenant Nathan D. White, 30, was killed April 2, 2003, when his F/A-18C Hornet was apparently shot down by a U.S. Patriot missile. The military said the incident remains under investigation.

“He just had the nicest personality. There wasn’t anyone who knew him that didn’t like him. He could tell great stories. He was just captivating,” said Ana Mitchell, White’s oldest sister.

White was the second oldest of eight children who grew up in Abilene, Texas. He spent two years serving as a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Japan.

He graduated from Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, and moved to Mesa, Arizona, to take a management job with a Dillard’s department store. After a year in Mesa, White applied to law school and the Naval aviation program, deciding eventually to enter the Navy.

“Nathan was a dreamer. The sky was really the limit for the possibilities he had,” Mitchell said from her Provo home. “It sounded exciting. It sounded challenging, intense.”

White, the son of an Air Force pilot who fought in Vietnam, was married and had three children. He was serving a three-year stint in Japan and was deployed to the Middle East with Carrier Air Wing Five aboard the USS Kitty Hawk.

Because White’s father and stepfather both served in the military during the Vietnam War, Mitchell said the family understands that friendly fire deaths sometimes occur during wartime.

“Mistakes happen that are tragic mistakes,” she said. “We feel terrible, but you can’t have hatred or malice toward the person that was just doing the best they could.”

Still, Mitchell said it’s frustrating knowing that her brother’s fighter jet was likely shot down by coalition forces.

“It didn’t have to happen. We’re trying to accept that and work through that. It’s frustrating that now he’s gone. Our own people killed him,” she said.

White is survived by his wife, Akiko, and children, Courtney, Austin and Zachary, who live in Japan.

Mitchell said White will likely be buried in Arlington National Cemetery but no date had been set by Tuesday. Other memorial services were planned in Japan and in Abilene, Texas, where his parents live.

14 April 2003:

Nathan White had faith — faith in his religion and faith in the military.

In an e-mail White sent to his family while fighting in Iraq, the Navy aviator said he trusted the officers conducting the war and hoped the effort would be worthy.

“Regardless of the destination, I feel I am trained and prepared for any mission or contingency,” White wrote. “I have to have faith that those at the helm have fully weighed the consequences and have determined that the resulting good will far outweigh the bad.”

White, the pilot of a F-A-18C Hornet, was killed April 2, 2003. The Navy believes his plane was brought down by a Patriot missile. The incident remains under investigation, the Navy said.

In a statement released by the Navy, his family said they are proud of him and that he died doing what he loved.

“Aviation was his passion,” the statement read. “He was a man who lived his dream. He died defending this country.”

He grew up in Abilene, Texas, and graduated from Cooper High School in 1991. After high school, White attended Brigham Young University. He spent two years serving as a missionary in Japan.

White was assigned to the Strike Fighter Squadron 195, based in Atsugi, Japan, and had been deployed with Carrier Air Wing 5 aboard the USS Kitty Hawk.

White’s survivors include his wife, Akiko, and his three children, Courtney, Austin and Zachary, who are all in Japan.

April 14, 2003:

AS SAYLIYA CAMP, Qatar – The U.S. military confirmed on Monday that a “friendly” Patriot missile probably shot down an F/A-18C Hornet fighter that came down over Iraq on April 2, 2003, killing the pilot.

Central Command in Qatar named the Navy pilot as Lieutenant Nathan D. White, 30, from Mesa, Arizona. He was based on the aircraft carrier Kitty Hawk.

The U.S. military had previously said it was looking into whether his aircraft may have been hit by a U.S. Patriot missile.

“Indications are that a Patriot missile shot down the F18,” a spokesman at Central Command said on Monday.

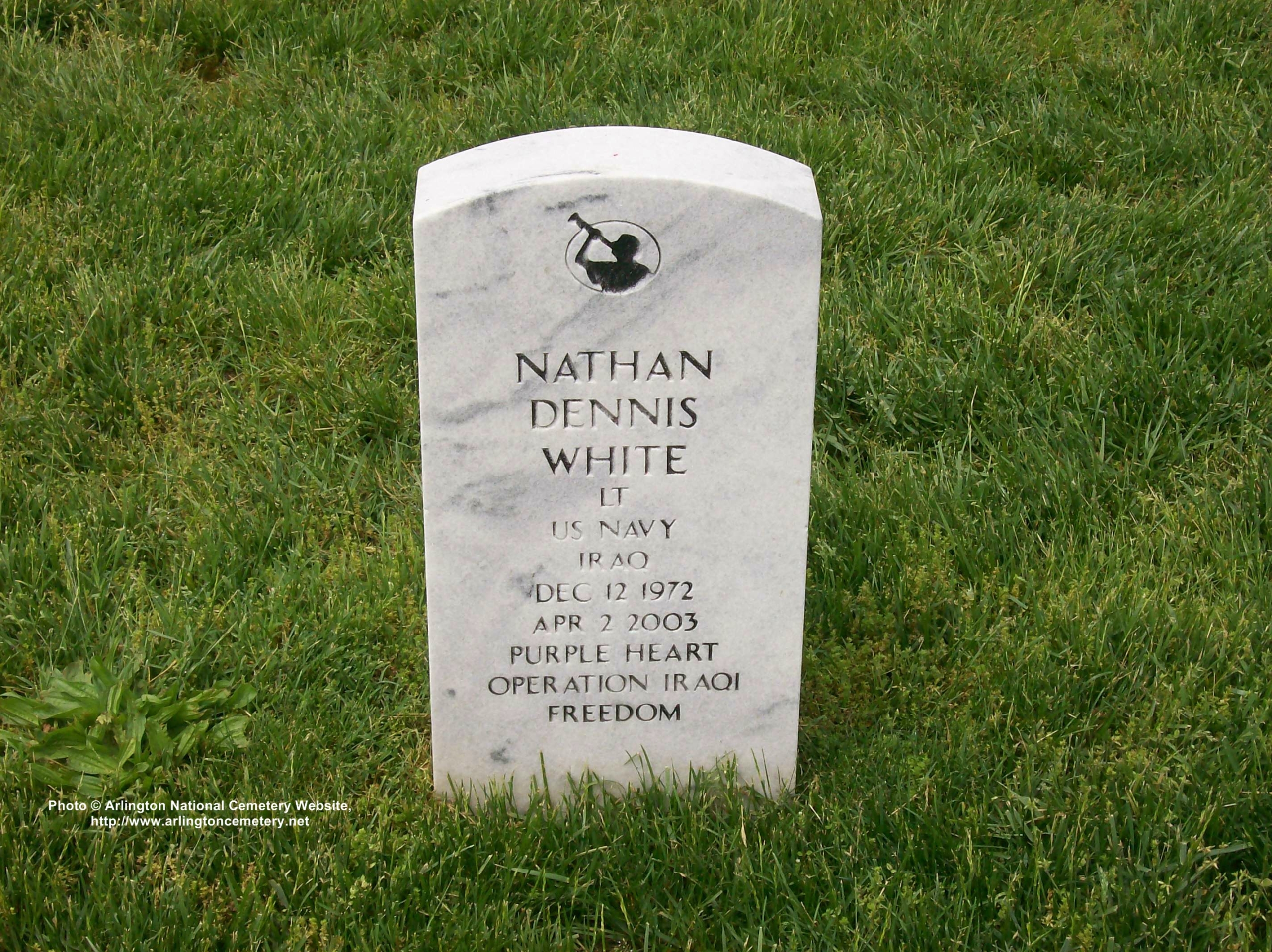

WHITE, NATHAN DENNIS

- LT US NAVY

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 09/05/2001 – 04/02/2003

- DATE OF BIRTH: 12/12/1972

- DATE OF DEATH: 04/02/2003

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 04/24/2003

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 7873

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard