Harriet Gowen

American Red Cross

Department of Defense Advisory: 11 August 1999

The remains of an American Army Air Forces officer and an American Red Cross employee have been identified and were interred in Arlington National Cemetery Friday, August 6, 1999.

They are identified as First Lieutenant Harold F. Wurtz Jr. of Dearborn, Michigan and Harriet E. Gowen of Stillwater, Minnesota.

On May 12, 1945, Wurtz and Gowen took off from an airstrip in Nadzab New Guinea aboard a two-seat P-47D Thunderbolt. The aircraft disappeared after take-off and aerial search missions on May 12th and 13th proved unsuccessful.

In 1996 a local resident of Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea found wreckage of a P-47 near his home. He enlisted the help of neighbors to recover the wreckage from the crash site. Amid the wreckage they found human remains and personal effects including a frame from a women’s pair of eyeglasses and an identification tag for “Wurtz, Harold F.” The tail number found on the wreckage matched that of Wurtz’s P-47. The remains and effects were turned over to the National Museum and Art Gallery in Papua New Guinea. The museum in turn released them to an U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory Hawaii representative in March of 1998. Two months later, a CILHI team excavated the crash site and recovered additional human remains.

In September of 1998 another CILHI recovery team received remains from the U.S. Embassy which had been gathered by local villagers prior to the May 1998 recovery.

Anthropological analysis of the remains and other evidence by CILHI confirmed the identification of Wurtz and Gowen.

More than 78,000 Americans remain unaccounted-for from World War II.

From contemporary press reports:

Harriet Gowen was a Red Cross worker who served during World War II as a recreation specialist at a military hospital in New Guinea. And Second Lieutenant Harold Wurtz was an Army Air Force pilot assigned to the Far East Air Force.

On May 12, 1945, a P-47 Thunderbolt piloted by Wurtz and carrying Gowen as a passenger took off from an airstrip in Nadzab, New Guinea, and disappeared.

Last Friday, more than 54 years after they went missing, the remains of Gowen and Wurtz were laid to rest in a single casket at Arlington National Cemetery.

A horse-drawn caisson drew the casket to the grave site, where Wurtz was given full military honors. Gowen’s niece, Ann Freeman, of Greensboro, N.C., was presented with a folded Red Cross flag.

“Even after 50 years, it was sad,” said Kelly Alexander, a spokeswoman for the American Red Cross.

Family members believe Gowen and Wurtz, who were both single, were friends who had gone for a joy ride, according to a recent story in the Greensboro News & Record.

The P-47 is a single-seat plane, but there is room for a passenger to fly piggyback if the back seat cushion that doubled as a parachute were removed. The plane may have run out of fuel, according to the story.

Wreckage of the P-47 was found by villagers in New Guinea three years ago and the remains eventually were recovered and identified as belonging to Gowen and Wurtz.

Red Cross officials believe Gowen is the first Red Cross worker to be buried at Arlington who did not have direct military connections, according to Alexander.

“We’re glad to have one of our own back,” said Alexander.

5 August 1999

A Greensboro, North Carolina, woman will put to rest a 54-year-old mystery as she goes to Arlington National Cemetery on Friday to bury the remains of her aunt, a former Red Cross worker, and the Army Air Corps pilot with whom she died in New Guinea in 1945.

“I think it’s that old cliche, that sense of closure,” says 61-year-old Ann Freeman, a Minnesota native who has lived in Greensboro for 22 years. “We wondered if they’d ever find her.”

Ever since she was 8 years old, Freeman has heard stories about how her mother’s sister, Harriet Gowen of Stillwater, Minnesota, went down in a plane in New Guinea, where she ran the officers’ club at a U.S. airstrip. The family didn’t know the circumstances of Gowen’s disappearance until three years ago, when a story involving ghost tales, ransom demands and wild pig hunting began to trickle out of the jungle.

According to old documents and new information, the story of Gowen’s disappearance began just after lunchtime on May 12, 1945, in Nadzab on the main island of New Guinea. The sky was blue, the Japanese had long been driven off the island, and the heart of the day was ahead. It must have seemed like the perfect time for the 28-year-old Gowen, an airplane enthusiast, to go up for a ride with her friend, 21-year-old Lt. Harold “Junior” Wurtz Jr. of Dearborn, Michigan.

Wurtz, who trained in Greensboro in 1943, and Gowen were seeing out the final months of World War II on the island.

Just before 2 p.m., Gowen borrowed a Jeep and picked up Wurtz, who was single, too, at the officers’ club. They rumbled to an airstrip and climbed into a dark green P-47 Thunderbolt fighter for a “local flight,” meaning they had no official mission. There was no other airfield nearby. Most likely, they planned to cruise over the surrounding jungle and mountains, see the blue Pacific and come back.

It didn’t work out.

By 4 p.m., they were reported missing. For three days, the Air Corps sent up several sorties to search for wreckage. A crew member for another plane had reported seeing a P-47 or something like it in a spin at 3,000 feet.

For three days, the Air Corps looked and found nothing.

Nobody found anything until three years ago, when three New Guinea natives left their village with spears and the village’s only rifle to hunt for wild pigs. When they reached an area they believed to be haunted, two hunters dropped out, fearing the story they’d heard over the years: When you get to the haunted place, the ground will shake and you will hear engine noises.

But one of the Christianized natives, Moses Paul, pressed on with the rifle and its single bullet. When he reached the forbidden territory, he said later, the ground shook and he heard engine noises. He was determined to see what was making the racket. He lay down by a tree and went to sleep. When he woke in daylight, he saw a huge hole in the ground and a piece of metal sticking out. He ran back to the village and got others to help him dig out the metal. They found more metal. And pieces of airplane. And human bones. And teeth. And the black oval frames of a woman’s glasses. And the dog tags of Lt. Harold Wurtz.

The site was five miles from the airstrip where Wurtz had taken off, in an area that was swamp in 1945.

A Lutheran church worker in a nearby town heard about the discovery. He faxed the news toanother church worker, who by coincidence, lived in Minnesota. The church worker contacted a radio newsman, who contacted Bryan Moon, a former Northwest Airlines executive who is interested in the recovery of World War II aircraft.

Moon searched declassified Air Force reports and found the missing craft report. With that, and Wurtz’s dog tags, he knew the natives must have found the crash site. He decided to go to New Guinea to find out what he could. But before he left, he received a message from the villagers. They wanted $15,000 for the remains.

“I sent back a fax saying, ‘That’s gross. Do you realize these people died fighting for your country?'” says Moon, 71, of Cannon Falls, Minn.

He went to New Guinea with his son, anyway.

“This was something we wanted to do,” Moon says. “There were two people who’d been missing for 52 years, and it seemed liked somebody ought to go and and bring them back.”

Moon and his son lived with the villagers for two weeks, gathering information on the crash site and remains, information they forwarded to the U.S. Army.

Along with the remains and personal effects, they saw pieces of the Thunderbolt’s fuselage and tail wings, four propellers, the main wheels and tail wheel assembly.

Moon offered the villagers $2,000 for their excavation work if they’d give him the human remains and personal effects. Thirteen of the 14 families agreed. The 14th family didn’t. Village custom called for unanimous decisions.

Moon warned that if they didn’t take the $2,000, the U.S. Army would come with local police and take the remains — with no compensation — after he left.

“That’s exactly what happened,” says Moon, adding that the 14th family is not popular in the village these days.

The Army identified the remains as those of Wurtz and Gowen.

Moon later talked to Wurtz’ squadron commander, who said he believed that Wurtz took up a plane that had just returned from a mission and had not been refueled. The plane, Moon believes, could have run out of fuel, a frequent cause of private plane crashes.

“People make the same mistakes in the military,” says Moon, an Englishman who served in the Royal Air Force just after World War II.

The no-fuel scenario would be consistent with the report of a plane in a spin at 3,000 feet, Moon says. The P-47 was a heavy plane with no gliding ability. The disintegration of wreckage at the crash site suggests that the plane was going very fast when it hit the ground.

Ann Freeman was hardly surprised at the news of her aunt’s fate. She says that her mother, now deceased, had little hope that Gowen could have survived an airline crash, but Freeman’s grandmother, also deceased, clung to the possibility.

“The word is that my grandmother never gave up hope.”

Freeman believes that Gowen, a petite, vivacious woman with reddish-brown hair, and Wurtz were just friends. She cites a Christmas card in which Gowen wrote of another officer.

The families of Gowen and Wurtz believe that the couple were flying “piggyback” when they crashed. The P-47 was a single-seat plane, but if the parachute that acted as a back seat cushion were removed, along with the parachute at the bottom of the seat, a passenger could sit behind the pilot.

Kenneth R. Wurtz of Long Beach, Calif., said that several days before his brother died he wrote in his pilot’s log that he carried another pilot that way on a training flight.

“They were on a joy ride, that’s what happened,” says Kenneth Wurtz, who describes his only sibling as “very shy and bashful” until he got into a cockpit. Once, when he was training in Mississippi, Harold Wurtz thrilled his little brother by squeezing a plane under a bridge that spanned a river.

Kenneth Wurtz was standing on the bridge, on his brother’s orders.

“He came up the river about 10 feet off the water.”

Though he was shy, his brother had no shortage of girlfriends, Kenneth Wurtz says. That was true while he was in Greensboro in 1943, training for high-altitude flights at the Army Air Corp’s Technical Command at the old Lindley Field, a site that’s now a part of the Piedmont Triad International Airport.

Harold Wurtz had a local girlfriend named Virginia. In the Philippines, he flew a plane named “Ginnie,” after her.

After he transferred to New Guinea, Wurtz had a picture of a woman — his brother assumes it’s Gowen — with “Our Red Cross Worker” written on it. In her personal effects, Gowen had a picture of Wurtz with “Hot Pilot” written over it.

On Friday, Kenneth Wurtz, Ann Freeman and other family members will watch as the remains of Lt. Harold Wurtz and some indistinguishable remains — his and hers — are lowered into the ground. Taps will play and rifles will fire, as the casket is buried with full military honors.

The following Friday, the remains positively identified as Harriet Gowen’s will be buried next to her mother in a small church cemetery in Minnesota.

Freeman, who moved to Greensboro with her husband, Charles, now a retired Burlington Industries employee, says she has no bitterness about how her aunt died, even if it was caused by pilot error. Gowen, who talked about learning to fly herself, came from a family of adventurous women.

Deciding to take an afternoon flight would be in keeping with her aunt’s fun-loving character.

“I’d do the same thing, absolutely, if I felt the guy was competent and the weather was fine,” Freeman says.

Greensboro woman has learned the story of how her aunt disappeared.

15 August 1999

A Greensboro woman will put to rest a 54-year-old mystery as she goes to Arlington National Cemetery on Friday to bury the remains of her aunt, a former Red Cross worker, and the Army Air Corps pilot with whom she died in New Guinea in 1945.

“I think it’s that old cliche, that sense of closure,” says 61-year-old Ann Freeman, a Minnesota native who has lived in Greensboro for 22 years. “We wondered if they’d ever find her.”

Ever since she was 8 years old, Freeman has heard stories about how her mother’s sister, Harriet Gowen of Stillwater, Minn., went down in a plane in New Guinea, where she ran the officers’ club at a U.S. airstrip. The family didn’t know the circumstances of Gowen’s disappearance until three years ago, when a story involving ghost tales, ransom demands and wild pig hunting began to trickle out of the jungle.

According to old documents and new information, the story of Gowen’s disappearance began just after lunchtime on May 12, 1945, in Nadzab on the main island of New Guinea. The sky was blue, the Japanese had long been driven off the island, and the heart of the day was ahead. It must have seemed like the perfect time for the 28-year-old Gowen, an airplane enthusiast, to go up for a ride with her friend, 21-year-old Lt. Harold “Junior” Wurtz Jr. of Dearborn, Mich.

Wurtz, who trained in Greensboro in 1943, and Gowen were seeing out the final months of World War II on the island.

Just before 2 p.m., Gowen borrowed a Jeep and picked up Wurtz, who was single, too, at the officer’s club. They rumbled to a dirt air strip and climbed into a dark green P-47 Thunderbolt fighter for a “local flight,” meaning they had no official mission. They was no other airfield nearby. Most likely, they planned to cruise over the surrounding jungle and mountains, see the blue Pacific and come back.

It didn’t work out.

By 4 p.m., they were reported missing. For three days, the Air Corps sent up several sorties to search for wreckage. A crew member for another plane had reported seeing a P-47 or something like it in a spin at 3,000 feet.

For three days, the Air Corps looked and found nothing.

Nobody found anything until three years ago, when three New Guinea natives left their village with spears and the village’s only rifle to hunt for wild pigs. When they reached an area they believed to be haunted, two hunters dropped out, fearing the story they’d heard over the years: When you get to the haunted place, the ground will shake and you will hear engine noises.

But one of the Christianized natives, Moses Paul, pressed on with the rifle and its single bullet. When he reached the forbidden territory, he said later, the ground shook and he heard engine noises. He was determined to see what was making the racket. He laid down by a tree and went to sleep. When he woke in daylight, he saw huge hole in the ground and a piece of metal sticking out. He ran back to the village and got others to help him dig out the metal. They found more metal. And pieces of airplane. And human bones. And teeth. And the black oval frames of a woman’s glasses. And the dog tags of Lt. Harold Wurtz.

The site was five miles from the airstrip where Wurtz had taken off, in an area that was swamp in 1945.

A Lutheran church worked in a nearby town heard about the discovery. He faxed the news toanother church worker, who by coincidence, lived in Minnesota. The church worker contacted a radio newsman, who contacted Bryan Moon, a former Northwest Airlines executive who is interested in the recovery of World War II aircraft.

Moon searched declassified Air Force reports and found the missing craft report. With that, and Wurtz’s dog tags, he knew the natives must have found the crash site. He decided to go to New Guinea to find out what he could. But before he left, he received a message from the villagers. They wanted $15,000 for the remains.

“I sent back a fax saying, ‘That’s gross. Do you realize these people died fighting for your country?'” says Moon, 71, of Cannon Falls, Minn.

He went to New Guinea with his son, anyway.

“This was something we wanted to do,” Moon says. “There were two people who’d been missing for 52 years, and it seemed liked somebody ought to go and and bring them back.”

Moon and his son lived with the villagers for two weeks, gathering information on the crash site and remains, information they forwarded to the U.S. Army.

Along with the remains and personal effects, they saw pieces of the Thunderbolt’s fuselage and tail wings, four propellers, the main wheels and tail wheel assembly.

Moon offered the villagers $2,000 for their excavation work if they’d give him the human remains and personal effects. Thirteen of the 14 families agreed. The 14th family didn’t. Village custom called for unanimous decisions.

Moon warned that if they didn’t take the $2,000, the U.S. Army would come with local police and take the remains — with no compensation — after he left.

“That’s exactly what happened,” says Moon, adding that the 14th family is not popular in the village these days.

The Army identified the remains as those of Wurtz and Gowen.

Moon later talked to Wurtz’ squadron commander, who said he believed that Wurtz took up a plane that had just returned from a mission and had not been refueled. The plane, Moon believes, could have run out of fuel, a frequent cause of private plane crashes.

“People make the same mistakes in the military,” says Moon, an Englishman who served in the Royal Air Force just after World War II.

The no-fuel scenario would be consistent with the report of a plane in a spin at 3,000 feet, Moon says. The P-47 was a heavy plane with no gliding ability. The disintegration of wreckage at crash site suggests that the plane was going very fast when it hit the ground.

Ann Freeman was hardly surprised at the news of her aunt’s fate. She says that her mother, now deceased, had little hope that Gowen could have survived an airline crash, but Freeman’s grandmother, also deceased, clung to the possibility.

“The word is that my grandmother never gave up hope.”

Freeman believes that Gowen, a petite, vivacious woman with reddish-brown hair, and Wurtz were just friends. She cites a Christmas card in which Gowen wrote of anotherofficer she had dated.

The families of Gowen and Wurtz believe that the couple were flying “piggyback” when they crashed. The P-47 was a single-seat plane, but if the parachute that acted as a back seat cushion were removed, along with the parachute at the bottom of the seat, a passenger could sit behind the pilot.

Kenneth R. Wurtz of Long Beach, Calif., said that several days before his brother died he wrote in his pilot’s log that he carried another pilot that way on a training flight.

“They were on a joy ride, that’s what happened,” says Kenneth Wurtz, who describes his only sibling as “very shy and bashful” until he got into a cockpit. Once, when he was training in Mississippi, Harold Wurtz thrilled his little brother by squeezing a plane under a bridge that spanned a river.

Kenneth Wurtz was standing on the bridge, on his brother’s orders.

“He came up the river about 10 feet off the water.”

Though he was shy, his brother had no shortage of girlfriends, Kenneth Wurtz says. That was true while he was in Greensboro in 1943, training for high-altitude flights at the Army Air Corp’s Technical Command at the old Lindley Field, a site that’s now a part of the Piedmont Triad International Airport.

Harold Wurtz had a local girlfriend named Virginia. In the Philippines, he flew a plane named “Ginnie,” after her.

After he transferred to New Guinea, Wurtz had a picture of a woman — his brother assumes it’s Gowen — with “Our Red Cross Worker” written on it. In her personal effects, Gowen had picture of Wurtz with “Hot Pilot” written over it.

On Friday, Kenneth Wurtz, Ann Freeman and other family members will watch as the remains of Lt. Harold Wurtz and some indistinguishable remains — his and hers — are lowered into the ground. Taps will play and rifles will fire, as the casket is buried with full military honors.

The following Friday, the remains positively identified as Harriet Gowen’s will be buried next to her mother in a small church cemetery in Minnesota.

Freeman, who moved to Greensboro with her husband, Charles, now a retired Burlington Industries employee, says she has no bitterness about how her aunt died, even if it was caused by pilot error. Gowen, who talked about learning to fly herself, came from a family of adventurous women.

Deciding to take an afternoon flight would be in keeping with her aunt’s fun-loving character.

“I do the same thing, absolutely, if I felt the guy was competent and the weather was fine,” Freeman says.

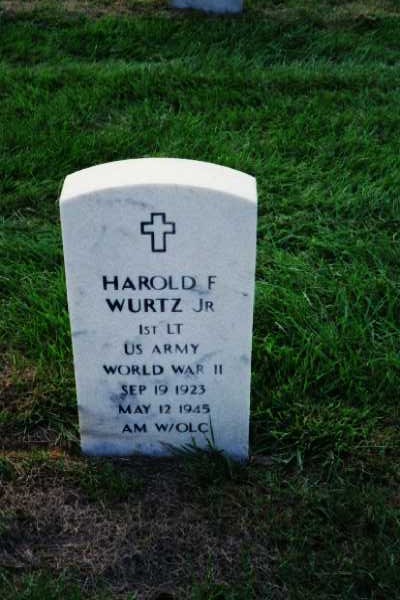

Wurtz, Harold F Jr

- Born September 19, 1923

- Died May 12, 1945

- United States Army, First Lieutenant

- Residence: Hermosa Beach, California

- Section 60, Grave 7827

- Buried August 6, 1999

Gowen, Harriet E

- Born May 11, 1917

- Died May 12, 1945

- Section 60, Grave 7828

- Buried August 6, 1999

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard