Delaware Valley Texas A&M Club Aggies:

I’ve saved this story for Muster week. Several weeks ago Bob Baggott ’69, editor of the Aggie Gram, was approached by one of his thousands of readers from around the world after reading an article that I had contributed to the Aggie Gram. It pertained to my old outfit, “A” Chemical Co. (This was really old army). The reader, Noel Garland, recognized it as the outfit that his high school buddy, Milton Roberts, had joined as a freshman. Noel had come down from Dallas to visit him in College Station where he met some of Milton’s classmates. Noel had aspired to attend A&M but various circumstances had prevented it. He never lost his love of A&M; however, and he was a long time subscriber to the Aggie Gram.

Bob Baggott referred him to me and he asked for any knowledge of his old buddy. I recounted that Milt (AKA “Snake” due to his long lanky stature) was a member of the Fish Drill team, a Distinguished Student, our company Guidon Bearer, a Ross Volunteer, our company exec officer, a Distinguished Military Student and an all round great guy with a big boyish grin and wonderful sense of humor. On graduation he had chosen to make his career in the regular army.

After that we lost touch. Between me and my classmates, we had very little information about him. We had heard that he became a helicopter pilot and had died during the Viet Nam era. No specifics.

Noel went to work contacting myriad sources to learn the rest of the story. After countless e-mails, phone calls, and personal visits, he was finally rewarded in locating and contacting the co-pilot of Milt’s helicopter, Bruce Valley. Bruce related that they were among an elite group of pilots, both rotary and fixed wing, who had amassed at least 2000 hours flight time, and they were attending an intensive program at the Naval Test Pilot School. During one of the test flights he and Milt had crashed into the Patuxent River in Maryland in freezing waters. Bruce somehow managed to survive, but Milt was killed in the crash. He confirmed what we had heard but could not confirm, that Major Milton R. Roberts was indeed buried in Arlington National Cemetery as he had attended his funeral.

As a final tribute, Noel arranged for a memorial to be posted on the ANC website. In addition to Milt’s accomplishments at A&M and in his military career, it includes a chilling first-hand, very detailed account of the final flight by his co-pilot. The memorial posting is a very moving tribute to a fellow Aggie, classmate and friend. During this Muster week I invite you to view it.

Two weeks ago, I traveled to Washington and met up with another of our classmates, Word Roberson. Together we located Milt’s grave and paid our respects. See photo below.

For all of Snake’s old buddies we greatly appreciate this bit of closure that was facilitated due to the networking provided by the Aggie Gram. Thanks to the diligent efforts of Noel Garland who must truly bleed maroon and to Bob Baggott for putting us in contact.

Milton R. Roberts was born in 1936 in Dallas, Texas, and was schooled there. He attended Texas A&M College from 1954 to 1958. A member of the Corp of Cadets there, graduating as a Civil Engineer, with memberships in the Fish Drill Team, and the honor unit, the Ross Volunteers. Also credited as a Distinguished Student, Distinguished Military Student, receiving a regular Army commission, and chose to go into Army Aviation. He served two tours in Vietnam in the Air Rescue operations, being injured severely, and returned to Brooke Army Medical Hospital in San Antonio until he was able to return to flying status.

Later information is that he had one son and one daughter, from Bruce Valleys recollection.

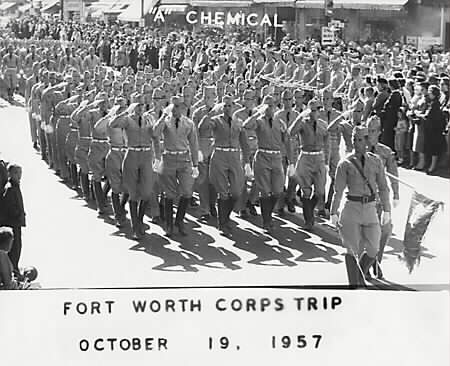

Milton is the cadet in the front rank, furthest on the left, saluting eyes front,

rather than the others who are facing the reviewing stand there in Austin

Photo Courtesy of Bob Coffey & Noel Garland

1967 Former Students Directory

Officer at Fort Benning, Georgia, married with one daughter. There is another address listed for McDonald, Ohio ,which I assume was maybe his wife’s residence while he was stationed in Georgia, but am not sure of that.

1970 Former Students Directory

Officer at Fort Rucker, Alabama, same biographical information, after that he is listed as deceased.

This from one of his A&M Corp classmates:

I saw Milton in San Antonio in 1966 or 1967. He was outpatient from Brooke General Hospital. He made no mention of burn injuries, but had a wrist in a cantilevered brace. He said he had caught a shell fragment through the forearm during a mortar attack that damaged a nerve. His fingers worked okay but when the brace came off his hand dropped at the wrist and he could not control that. He said that surgery to repair the nerve was scheduled and he hoped that success would let him go back on flight status. Obviously it worked.

I met his wife at the time but cannot remember her name or anything about children. I have no idea where is buried, and know nothing of widow/children.

I am a bit leery about talks of secret projects. Have heard too much of that from my time in the service. Most of that is bull as folks in such projects seldom talk about it. Milton did not mention such to me.

Do not know if he was ever at Edwards Air Force Base, but he was selected for Test Pilot School at PAX River Naval Air Station which is a really big deal. The selection rate for pilots from all services is minuscule. Test pilot school was a prerequisite for the astronaut program but all in the school were not intended to go into astronaut program; so I cannot say whether Milton was slated for astronaut program (suspect he might have been too tall).

A copy of the Popular Mechanics article, September, 1971, relates about his and others experiences and deaths in helicopters, titled, “Unsafe at Any Height.”

From: Bruce Valley

To: Noel Garland

Sent: Saturday, March 26, 2005

Subject: Re: Questions about the life of Milton Roberts

Good morning, Noel — Here are the answers to your questions as best my memory can retrace events of 35 years ago. I may have given too much information on some. But, obviously, you can use what you wish. For reasons I cannot explain, this recollection and report was also somehow good for me. Sincere regards, Bruce

Bruce:

Here is a list of quick questions that come to mind, I may have more, and some of these you may be able to combine in quicker, or fewer answers. I leave it up to you as to what you can or will answer, hopefully the answers wont be difficult to come by, or be too painful memories considering the friendship you had or feel about Milton. By the way, I have recently learned that his Corp nickname was Milton (Snake) Roberts, something his friends at A&M don’t remember or know how he came by that. I never heard him referred to by a nickname in high school, he was just always Milton. I know he and a good friend here were avid miniature golf players, and may have played golf also.

Regards, Noel

Questions:

When did you first meet Milton?

October 1970, as Class 58 convened at the US Naval Test Pilot School, Patuxent River, Maryland. Twenty-one (21) of the military’s hottest pilots, including five (5) helicopter pilots (Major Milton Roberts, USA (Leader), Captain Morrie Larson, USA, Captain Fred Gregory, USAF (later an astronaut and shuttle commander, now deputy director, NASA), myself, and a Marine Corps Captain who dropped out in the first week).

You mentioned some knowledge of Milton’s helicopter experiences that he had in Vietnam. I understand from his mother that he was burned severely on the arm coming out of the mess hall in the DaNang mess one morning due to a mortar or rocket attack. He then spent months at Brook Army Medical Hospital in San Antonio until he was able to regain his flying status and thus remain in the Army. What knowledge do you have of these periods in his life?

My recollection of Milt’s background (though aviators will talk ceaselessly about their airplanes, fast cars and girlfriends, most do not discuss themselves in detail!) is that he’d had two or three Vietnam tours. On the last his left wrist was terribly damaged, eliminating him from further flight status (that hand has to pull the collective up and down, controlling the rotor pitch and thus altitude, but also must twist that lever to control the engine rpm). Milt rehabilitated himself somehow and was able to return to flight status. He had over 3000 hours in the Huey (UH-1) helicopter and was a masterful pilot.

When did you both begin the Test Pilot School, and where was training performed?

See question one (1) above. The course was one year in length, with the rotary wing pilots required to complete both fixed and rotary wing courses (some 28-30 test flights each), while learning to fly some forty different airplanes or helicopter and attending school (master or Ph.D. level math and aero) one half day each weekday.

What was the course of instruction in both classroom and in flight training?

See above. The content of all courses was intended to prepare the (primarily Navy) pilots for duty in the test divisions of NATC (the Naval Air Test Center) at Patuxent River, where they would typically serve for three years following completion of test pilot school. These divisions, like the course content, were Flying Qualities & Performance (the two subjects upon which the school concentrated), Weapons Systems Test and Service Suitability.

You mentioned 30 flights in fixed wing aircraft, and 30 flights in rotary wing aircraft. Why was it necessary for experienced helicopter pilots to take 30 additional flights in helicopters when the fixed wing pilots did not have to accomplish that?

This is opinion : It would be preferred that all test pilots be trained as unrestricted (ie. certified to test anything, fixed or rotary wing). But the reality was that the test flying of a helicopter was much more dangerous than that of a fixed wing aircraft. Having fixed wing pilots become qualified as rotary wing test pilots would have greatly heightened the fatality rates (which was already 10-20% per class, I believe). Finally, while I believe based on thousands of hours of flying helicopters that they are just as safe as airplanes, their inherent instability makes them far harder to fly in test regimes beyond normal flight parameters. Thus survival doing such tests depends significantly upon experience, which the fixed wing pilots would not have had. All of Class 58’s helicopter students had at least 1000 hours of flying time in helicopters and had flown in combat.

What knowledge did you have of Milton’s family and life outside of the training?

Like my family, Milt’s home life was quiet and normal. That was a hard drinking, hard living time and neither Milt or I drank or partied. Milt had a lovely wife (Amanda) and two small children (4-8?), one boy and one girl. I know little else but my impression was that Amanda’s family lived around Washington, DC.

What common experiences did you and Milton have outside of the training and classroom experience if any?

Due to the 24 hour pressures of the school, there was precious little time to do anything else. Milt and I — and the other helo drivers — spent a lot of time together at the school or in one of our homes studying. The academics were incredibly rigorous and often required all-nighters to prepare for the next day. As I recall we did occasionally get together for a Friday or Saturday night bring-your-own dinner at someone’s home, where we would all sit around and complain how demanding the school was.

What are the details of the crash as you remember them?

The date was January 22, 1971. We took off early at 7 AM. The test was Climb To Service Ceiling, which required us to fly the UH-1B to fly to an altitude greater than 20,000 feet where the air is thin and controls are mushy. It is very dangerous flying and I believe another helicopter and crew were lost doing this test a few years earlier. We were supposed to take along two flight engineers as cabin observers — one Italian and one Japanese — but the maintenance crew had forgotten oxygen equipment for those two and Milt elected to leave them behind. The day was overcast and calm, so calm that it was difficult to see how high you were above water which reflected the clouds. Navy pilots live in this environment often flying from aircraft pilots but Army pilots do not. Though Milt was the A/C (aircraft commander), I discussed this with him because our test climb required that we fly very low to begin ascent and obtain our data. He acknowledged, and added that he wouldn’t want to crash at sea because he could not swim well. We began our test with me flying the aircraft and Milt managing the data panels and stop watch. I believe the first of several climbs was at 40 KT. At 1000 ft I heard Milt say “Damn”. He had hit the stop watch but failed to start it and we would have to repeat the climb test. He took over flying the aircraft, and asked me to reset all the switches in the dashboard to zero so the flight data recorder would be ready to restart. I was still doing this when we hit the water in a steep right turn flying at perhaps 100 kts. I remember an explosion (the engine), being struck by something and then my mouth filled with water. At impact, my first thought was we’d had a mid-air collision with another aircraft. The aircraft was under water immediately (or I may have been briefly unconscious). I started to extricate myself but was pinned in by the instrument panel and could not release the seatbelts (we were wearing parachutes and oxygen masks for this test, which complicated things considerably). By the time I finally got free the aircraft was sitting upside down on the bottom in about 70 feet of water. I reached over to the pilot’s seat, which was empty (I later was told that Milt had gotten free but had gone into the cabin where he was trapped, though they also said he would not likely have survived his head injuries had he escaped the helo) and swam free (the door was gone) into the blackness, eventually reaching the surface.

There was wreckage, an oil slick, two helmets but no Milt. I assessed my situation. The water temperature was 32 degrees (as the Survival Officer of a Navy Squadron that had flown missions above the Arctic Circle, I knew my time to live was approximately 10-12 minutes in those conditions). I was in the middle of the Patuxent River, with ice chunks all around, and the nearest land was roughly one-half mile way. I took a chunk of floating fuselage for support and began to swim to the western shore. Though typically it is best to stay near the wreckage offering more of a target to searchers, I knew I had very little time and could not expect rescue in the time I had to live. After one-half hour I had made it about half way to shore. At that time a police boat passed me perhaps 300 feet nearer the shore heading south. But I had no voice and only my shoulder and hip joints still moved, everything else now being frozen. The boat, whose radio transmissions I could clearly hear above the engine noise, did not see me and, for the first time, I felt my hopes flag. But I kept swimming, turning on my back to help keep my mouth out of the water, and abandoning the piece of wreckage.

Some time later I heard an outboard motor. Looking up I saw a small rowboat heading north then, seeing me, it came alongside. The man, L. Ray White, had heard my initial cries for help or perhaps the sound of the crash itself, and come to investigate. Somehow this 140 lb man got a wet and disabled 200 lb aviator into his boat. He took me to his home on Cuckhold Creek, sat me before his stove and called the ambulance, which rushed me to the Navy Hospital. My body temperature was 85 degrees, right at clinical death. After 2-3 hours sitting on a stool in a hot shower, I was able to lie down. By the end of the day, I was able to go home.

What caused the crash to occur?

Like almost all accidents, the cause must be speculative. I would guess that Milt was fooled by the images of clouds in the water and did not closely monitor his altitude. The flight conditions, his unfamiliarity with over-water flight, and the wearing of parachutes and oxygen masks may all have contributed to the accident. I have always blamed myself for not checking outside while re-setting dozens of switches but both of us were feeling pressure for the time we’d lost due to the stop watch not working, and I will have to live with the rest.

What was the day and the flight like prior to the crash?

See above.

Who recovered Milton’s body as well as the helicopter?

A barge and crane recovered the helicopter before dark on the day of the crash with Milt’s body inside. The helo was brought to the test pilot school hanger for the accident investigation.

Where is Milton buried? Some reports say that he is buried in the Arlington National Cemetery but that proof cannot be found on the Arlington National Cemetery websites that I’ve looked at.

I attended Milt’s funeral with Class 58 and the USNTPS staff at Arlington National Cemetery.

Was there an investigation into the crash?

Yes, as there is for all military aircraft accidents. Somewhere I may have a copy. No one was found to be at fault in the crash.

Where is Milton’s family now, do you continue to have contact with them?

I regret to say that I have no idea. I hope Amanda was able to remarry.

Bruce,

I have included the second message in this letter to keep everything together, as the others involved in this search for answers will receive this letter at the same time as Im replying to you.

Noel

Photo Courtesy of Bob Coffey & Noel Garland

Noel — Here’s the answers to your set of follow-up questions. Hope this may be of assistance. Best regards & a wonderful Easter Weekend, Bruce

On Friday, March 25, 2005, at 07:54 PM, Noel Garland wrote:

Bruce,

Now I thought that we need to finish up the story, your story to complete the report.

What were your injuries, and/or experience in the water? We have the name of the fisherman who rescued you. By the way do you have a copy of that issue of the school graduation notice?

No injuries to speak of — just cuts and scratches. To say I was lucky is perhaps an understatement. I did dream of the crash for many years, and would wake up with huge, uncontrollable shivering. And my lower back was apparently damaged, as the doctors recommended fusing several sections to reduce pain. I choose not to have the operation, accepted the pain and stiffness for about a decade, then found myself pain free thereafter.

What effect did it have on you immediately afterwards, and later during the remainder of the training?

Obviously, I felt a sense of guilt that a friend had died and, somehow, I had lived. My emotional visit with Milt’s family the day after the crash remains one of the most intense experiences of my life. Going to his funeral and burial were very difficult experiences for me. Captain Fred Gregory, USAF (later an astronaut, shuttle commander and now deputy director of NASA) came to my house the afternoon of the crash to tell me we had to go flying the next morning. I was dumbfounded! He said I was too good a pilot to quit but that, if I didn’t get back in the air right away, I might give up flying. So at 7 AM the next morning, we took off in an old Sikorsky UH-34 Seahorse helicopter. My recollection is that the act of lifting the collective and pulling the aircraft into the air was very difficult to do — for the first time, opposing forces existed in my brain newly aware of the risks in that action — but having done so, lifted into a hover, and translated to forward flight, it felt normal and thereafter I never let the crash bother me again, flying for some fifteen more years and perhaps 3000 plus more flight hours.

Did it have an effect on your future career in the Navy?

None. Although I chose to retire after twenty commissioned years (and four previous at the U.S. Naval Academy), I felt I had a wonderful career with many unique opportunities. The helicopter crash played no further role in my naval career, except that for many years flight surgeons would call or write me annually to ask questions. It seems that my 45-50 minutes surviving 32 degree water, then surviving severe hypothermia, was some kind of record. During my career, I was privileged to personally serve a NATO Commander in Chief, A Secretary of the Navy, A Secretary of Defense, the first Director of Strategic Defense (Star Wars program) and, on occasion, two US Presidents, Reagan and Bush, Sr. — and to graduate not only from the US Naval Test Pilot School but also the Naval Postgraduate School (M.S. Management) and the Naval War College — and to spend one year as a Federal Executive Fellow.

What effect did it have on the remaining members of the class as far as you know?

Milt Roberts, in addition to being the senior helicopter pilot and thus our class leader, was the kind of officer and man that was well respected and well liked by everyone. His loss, under the extreme pressure of the test pilot school and its schedule, was keenly felt by not only his fellow students but by the staff as well. Having said that the business of testing aircraft — and of training test pilots — has always been expensive in human life. These sacrifices hopefully enable the saving of many more lives out in the fleet because test pilots have found ways from their test results to make the aircraft more safe or reliable. Military professionals do not often show their feelings when their friends and squadron mates are loss. They cannot, because they have to go right back into the cockpit and the air themselves. But, inside, they feel these losses just like anyone else — though it does not show.

One other question about Milton’s wife, did she come from McDonald, Ohio, or elsewhere, if you have that information?

Regrettably, I have no information about Amanda or the children — and do not know what her hometown may have been.

ROBERTS, MILTON R

MAJ US ARMY

DATE OF BIRTH: 08/29/1936

DATE OF DEATH: 01/22/1971

BURIED AT: SECTION 10 SITE 11301

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard