4 October 2006:

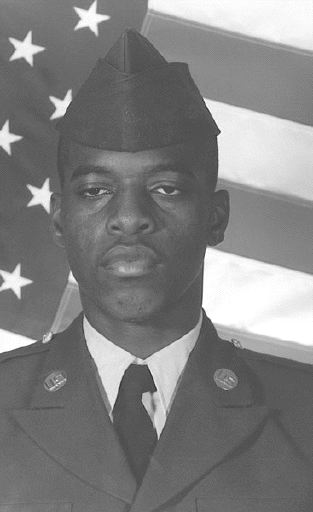

Sergeant Michael A. McQueen II, a U.S. Army Ranger, passed away Tuesday, September 26, 2006, in Gaithersburg, Maryland. Sergeant McQueen is a descendant of the Eubanks family of Lincolnville and Collier Heights in St. Augustine, Florida.

Sergeant McQueen had just returned from his third tour of duty in Afghanistan, where he had worked as a military intelligence analyst with the 75th Ranger Regiment. While in the States, Sergeant McQueen had been based at Fort Benning, Georgia.

This was Sergeant McQueen’s last tour of duty overseas and he was in Maryland preparing to enroll in January in the University of the District of Columbia, where he intended to study for a bachelorms degree. He is a 2002 graduate of North Miami Beach High School.

He enlisted in the Army soon after completing his studies at North Miami. After basic training at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri, McQueen received airborne training. He soon completed the requirements to become a U.S. Army Ranger and was deployed to Afghanistan three separate times in support of the Joint Special Operations task force. While there, his high-security clearance allowed him to work with a variety of U.S. intelligence agencies and his work took him to several Middle Eastern countries in support of Operation Enduring Freedom.

He was promoted from private to specialist in between stints in Afghanistan and was promoted posthumously to Sergeant.

McQueen was born in Tallahassee, Florida, and moved to Miami when he was 5. He attended Coral Way Elementary, Ponce de Leon Middle School, Archbishop Curley High and then North Miami Beach. While at Ponce, he was on the golf and tennis teams. At Curley, he was a defensive back on the football team, and a sprinter for the track team.

Survivors include parents, Michael and Glenda McQueen of New Orleans; brother, Otto McQueen of New Orleans; aunt, Nichole Brewton and her daughter, Brandi, both of Pembroke Pines; great-aunt, Joyce Holmes of Fort Lauderdale; uncle, Christopher McQueen of Macon, Georgia. He was preceded in death by his grandparents, Otto and Carolyn McQueen of Miami.

Services will be at 1 p.m., Saturday, October 7, at St. Cyprianms Episcopal Church, 37 Lovett St., St. Augustine, Florida. St. Cyprian was the family church for Sergeant McQueen’s great-grandparents, Frank and Myrtle Eubanks, and their children: Joyce, Carolyn, Edwin, Cynthia and Rodney.

A viewing is scheduled for 5 to 9 p.m., Friday, Oct. 6 at Leo C. Chase & Son Funeral Home, 262 W. King Street in St. Augustine. A full military honors burial to be held later at Arlington National Cemetery. Condolences and other correspondence can be directed to Michael and Glenda McQueen, 416 Vallette St., New Orleans, Louianana 70114

With Murder Trial, Family Seeks Truth in Son’s Death

‘Here’s a young man, a member of the U.S. Army Special Forces — a ranger. He’s not just some statistic.’

By Ernesto Londoño

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Thursday, November 15, 2007

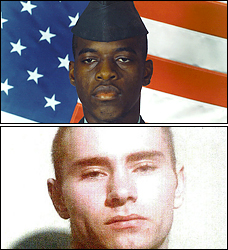

U.S. Army Ranger Michael McQueen had served three tours with special forces in Afghanistan, only to die in the living room of his Gaithersburg apartment after watching football, a .38-caliber bullet piercing his right temple.

Outside the apartment building, police later found his roommate, former Sergeant Gary Smith, crying inconsolably, smeared with McQueen’s blood and with gunpowder residue on his hands. Smith told police that before calling 911, he drove to nearby Lake Needwood, gun in hand, and dumped it in the water.

A Montgomery County jury is expected to decide in February whether Smith, 25, killed McQueen, 22, on the night of August 25, 2006, or simply tried to cover up a suicide. Smith is charged with first-degree murder.

The two conflicting theories point to largely unseen fronts in ongoing wars, battles that are often fought after veterans return home. Burdened by memories of war, some veterans commit crimes of violence, even killing, that they might not have otherwise, while others direct the violence inward, according to studies. The most desperate take their own lives.

An estimated 5,000 veterans of all wars commit suicide each year, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs, a trend that has led to congressional hearings and calls for an overhaul in post-combat screening. About one in five Iraq veterans suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, as does Smith.

The mystery surrounding McQueen’s death deepened recently when a blood-spatter expert hired by the prosecution concluded that the fatal gunshot wound appears to have been self-inflicted, a finding at odds with the conclusion of the state’s initial expert.

“Everyone has different opinions,” said Warrant Officer William Burkett, who supervised Smith and McQueen. “Some people don’t know what to think. Some people think he’s innocent. Some people think he’s guilty. Others, like me, think it’s not so black and white. Maybe he did it. Maybe he didn’t do it. Maybe he didn’t mean to do it.”

McQueen’s parents say they’re convinced that their son was killed, and worry that the charges could be dropped before they find out what happened that night. “I need the truth,” Michael McQueen said of his son’s death. “I can’t deal with a version of the truth.”

McQueen, 51, was at the Associated Press bureau he runs in New Orleans when he received a call about 18 hours after his son’s death.

“Your son is dead,” a detective told him.

“How did that happen?” the stunned father asked.

“Undetermined,” McQueen recalled her responding. Someone shot him or he shot himself.

McQueen had a barrage of questions: Had the shot been fired at close range? Was there gunpowder residue on his son’s hands? On the roommate’s? Would police treat the case lightly because his son was black?

As he drove home to break the news to his wife, Glenda, 51, and their younger son, Otto, 20, the conversation reeled in his mind.

“Here’s a young man, a member of the U.S. Army Special Forces — a Ranger,” he said. “He’s not just some statistic, just some black guy with a gunshot wound to the head.”

Prosecutors have disclosed no motive, and both sides point to evidence that supports their case: Gunpowder residue is present on both men’s hands.

Smith’s attorney, Andrew Jezic, has said his client is innocent. Smith, who grew up in Montgomery County, told a defense psychiatrist he was loyal to Michael McQueen, to a fault. Smith said he discarded the gun in the lake and later lied to detectives because he didn’t want his Army buddy to be remembered as a drunken, despondent veteran, according to a report in the court file. The cover-up, Smith said, was a misguided attempt to salvage what remained of McQueen: his legacy.

Growing up in South Florida, McQueen never took himself too seriously, his parents said, making just enough effort in school to stay afloat. His jovial, disarming personality made him enormously popular: At times his group of friends seemed more like an “entourage,” his mother said jokingly.

After graduating from North Miami Beach High School in 2002, he joined the Army. He didn’t want to go to college right away, his parents said, and the September 11, 2001, attacks ignited a sense of duty. The McQueens weren’t crazy about the idea, but his father said, “We trusted his judgment.”

Military life changed McQueen. After basic training, he joined the elite 75th Ranger Regiment and, as an intelligence officer, traveled extensively through the Middle East and Europe with CIA and military intelligence personnel, his parents said.

If he saw combat or was haunted by any aspect of his service, he never mentioned it, they said. He spoke about his work proudly but provided few details.

“He went into the military as this very playful boy,” Glenda McQueen said. “When he came back, he was a man. He was still himself. But he was a man.”

Smith, on the other hand, came home deeply scarred, said psychiatrist Thomas A. Grieger, evaluating him for the defense. In the 2003 Iraq invasion, he “saw extensive death and killing,” Grieger wrote, and “personally witnessed the death of a close friend and several soldiers.”

Smith and Michael McQueen served two tours together in Afghanistan, in 2004 and 2005. After returning home in 2005, Smith struggled with nightmares about Iraq and tried to suppress memories of combat, Grieger wrote. “Smith felt unsafe and for many months slept with a pistol under his bed,” he wrote.

Smith began drinking heavily and smoking marijuana to blur the memories of war and ease his angst, Grieger wrote. After the shooting, the VA diagnosed Smith with post-traumatic stress disorder, he wrote.

About one in five veterans returns from Iraq with the disorder, and about 12 percent report abusing alcohol, according to Army research released this week. One percent to 2 percent expressed thoughts of suicide or aggressive behavior. A survey of newspaper accounts found that almost 20 veterans have been charged with murder in the past few years in the United States.

Burkett, the former supervisor, doubted that Smith saw the carnage in Iraq he described. “I would have been one of the first to hear about it,” he said in a phone interview from a foreign posting.

Jezic, Smith’s attorney, said Burkett was not present at the time.

After thinking about McQueen’s death for more than a year, Burkett, who is likely to testify for the prosecution, said he has reached this conclusion: The two soldiers were drunk, and perhaps stoned, that night. Smith, who loves weapons, was fooling around with a gun. He pulled the trigger, killing McQueen, then panicked and made up a story.

Burkett and McQueen’s parents say Smith has been untruthful in describing McQueen as one of his two best friends.

“They interacted with each other because they worked together,” Burkett said. “I don’t think it was a very close relationship.”

McQueen returned home from his third and last tour in Afghanistan in July 2006 and was awaiting his discharge when he moved in with Smith after another roommate arrangement fell through, McQueen’s father said.

Smith told Grieger that McQueen drank heavily and smoked marijuana in the weeks before he died. He said McQueen was distraught over a recent breakup with his high school sweetheart, lukewarm about college and worried about his work prospects.

The McQueens say that receipts from their son’s credit cards show he purchased a lot of alcohol during those days and that he might well have smoked marijuana. He received two driving under the influence citations, which his father said were dismissed. His parent strongly reject the notion that McQueen was despondent.

A few days before his death, McQueen made copies of his résumé for a job fair the next week, his parents said. That weekend, he went to the cleaners to pick up his new $500 blue pinstripe suit. He had enlisted in the Army Reserve and was expecting a $10,000 sign-on check. He told his parents he wanted to study international law.

The day before he died, McQueen called his mother: He was going to entertain people at home and wanted her shepherd’s pie recipe. It was an unremarkable conversation. He seemed fine, she said.

The night he died, McQueen and Smith went to the Veterans of Foreign Wars post in Gaithersburg and later to a pool hall. Then Smith drove McQueen home.

The first officers who arrived at the apartment found Smith outside, crying on his hands and knees. He had blood on his hand, neck, shoe and pants. Officers found McQueen on a chair inside and blood on the carpet, but no gun.

Smith initially told detectives he left the apartment after dropping McQueen off and returned to find him dead, with no gun in sight. Then he told detectives he found McQueen slumped on a chair with a gun in his hand. Lastly, he said he was in the apartment when McQueen shot himself.

The McQueens have limited the number of photos and mementos of their late son on the walls of their home. But reminders are everywhere: Glenda McQueen drives his Chevrolet Tahoe, with its 24-inch rims and a powerful sound system. Her husband wears his dog tags.

They wonder, anxiously, whether a jury might be influenced by their son’s race. Michael McQueen checks on the case on the state’s judiciary Web site at least twice a day.

Since his son died, he gave up a wine blog and instead writes about the status of the case in straightforward dispatches posted on a Gaithersburg blog. He prays the case will go to trial.

“I’m a father,” he said. “You have to protect your children, whether they’re alive or dead. It’s my job.”

MCQUEEN, MICHAEL ANTHONY II

SGT US ARMY

- DATE OF BIRTH: 07/24/1984

- DATE OF DEATH: 09/26/2006

- BURIED AT: SECTION 54 SITE 516

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard