![]()

Closure for the family and relatives of retired Master Sergeant Max Beilke, nited States Army, came on December 11, 2001: he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors, three months to the day following his death.

Beilke, deputy chief of the Retirement Services Division, of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, was meeting with Lieuenant General Timothy Maude and retired Lieutenant Colonel Gary Smith at the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, when a hijacked jet piloted by terrorists hit the outer ring of the building. The three men and 71 other personnel were killed.

Lori Wells, of Brookings, joined high-ranking Army officials who took part in services to honor Beilke, her uncle. First came the funeral services in the military chapel at Fort Myer, Virginia, attended by General Eric K. Shinseki, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, and Major General Kathryn G. Frost, the Army’s Adjutant General. And following the burial ceremony at Arlington, which included a bugler playing Taps and a 21-gun salute by a firing squad, Frost presented an American flag to Beilke’s widow, Lisa Beilke.

Wells praised the American Red Cross, who paid for her and other relatives and family members from around the country and abroad to travel to the Washington, D.C., area to attend the services for her uncle.

Wells said she was the only relative from South Dakota to attend the funeral and burial services. Others who the Red Cross got to the services were Wells’ mother and Beilke’s sister, Lucille Johnson, two of Wells’ aunts, and three cousins, all of whom live in Minnesota, and an aunt and uncle of Wells, who live in Oregon.

“The Red Cross was great,” Wells said. “It made it easy for us to go. They just took care of everything. They took care of our hotels. They gave us money for food. They took care of the plane.”

In addition to being impressed with the Red Cross helping out the family and relatives, Wells was impressed with the military funeral for her uncle and how the Army looked after his widow.

“The Army has done so much to support my aunt,” she said. “It’s something I’ll never forget.”

Wells found out about her uncle’s fate from her mother, Lucille Johnson.

“I called my mom that day (September 11) and asked her if she had heard from him. His office was in Virginia, but he spent a lot of time in the Pentagon,” Wells said. “She said she had called Lisa, Max’s wife. Lisa said Max usually called her every morning, just to check on her. And she hadn’t heard from him. Even that night, they hadn’t heard from him. And then (Lisa) kind of knew.

“A general came and visited her and said they just couldn’t find him.”

But she said Lisa Beilke wanted to wait a while before holding funeral services. Wells added that DNA testing of some parts of the human remains found in the damaged section of the Pentagon were identified as belonging to her uncle.

And, Wells said, “It was such an intense fire. His death was probably instantaneous. They said he never knew what hit him, which helps.”

Wells said she had not seen Beilke in about seven or eight years. But she knew about his interesting Army career, which made Beilke a legend of sorts in the Army and among his family and relatives.

The 69-year-old Beilke, a native of Pipestone, Minnesota, who was drafted during the Korean War, stayed in the Army until his retirement in 1974, which was followed by a second career as a civil servant. During his 22 years on active duty, he served in Korea, Germany, and Vietnam. It was his tour in Vietnam during 1972 and 1973 that brought him a unique place in the history of our long struggle there.

Max Beilke was the last official American combat soldier to leave Vietnam. And he did so with his family watching on television.

A report following his death quoted his sister, Lucille Johnson, as saying, “We could see him leaving (Vietnam) on television. We all just beamed, because we knew he’d soon be home safely.”

Grim and hushed, the last U.S. troops filed onto a C-130 at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut Airport.

It was March 29, 1973. Under the terms of the negotiated peace agreement with North Vietnam, all U.S. combat troops were leaving Vietnam, though small numbers of support troops would remain.

Colonel Bui Tin, head of the North Vietnamese observer team, attempted to shake hands with the departing soldiers. Most ignored his outstretched hand, and one American spat out an obscenity.

Army Master Sergeant Max Beilke was the last in line.

As Beilke stepped up on the ramp to the plane and news crews recorded the moment, Tin held out a rattan mat adorned with a painting of a pagoda and offered it to the American.

“I hope you return as a tourist. You are certainly welcome,” Tin told Beilke, the Vietnamese officer recalled in a recent interview.

Beilke looked at Tin, accepted the present with a quiet word of thanks and climbed into the aircraft, Tin said.

Beilke, a Minnesota farm boy who was drafted in 1952 and sent to fight in the Korean War, retired from the Army in 1974. He eventually settled in Laurel with his wife, Lisa, and went to work for the Army as a civilian.

His colleagues knew him as a font of knowledge about veterans’ issues, but few knew about his moment of fame. “Oh yeah, just one of those things,” Beilke said when his colleague Martha Carden asked him about it.

Tin, reached by telephone in Paris, where he is now a leading critic of the Hanoi government, expressed sorrow at Beilke’s death. “I am very, very sad,” Tin said.

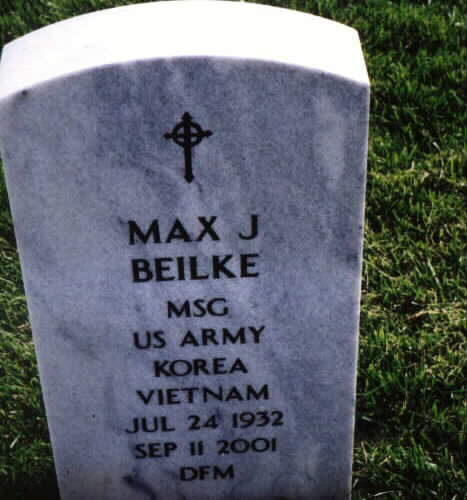

BEILKE, MAX J

MSG US ARMY

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 11/01/1954 – 11/01/1974

- DATE OF BIRTH: 07/24/1932

- DATE OF DEATH: 09/11/2001

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 12/11/2001

BURIED AT: SECTION 64 SITE 4639

Last Soldier to Leave Vietnam Is Feared Dead

Victims: Retired Army man Max Beilke, who survived two wars, was enjoying a

second career at the Pentagon assisting veterans.He was last in the line moving up the ramp into a waiting C-130 at Tan Son Nhut air base–a tall, husky man with an open Midwestern face who was about to step into history. It was March 29, 1973, in Saigon. And Master Sergeant Max Beilke was officially designated as the last American combat soldier to leave Vietnam.

He had survived two wars, Korea and Vietnam. Now he was going home to his

family in Minnesota.

Twenty-eight years later, Beilke–at 69 long since retired from the Army but pursuing a second career helping veterans–was suddenly plunged into his third conflict: the war of terror. Defense Department officials have added his name to the list of those believed killed when a hijacked airliner hit the Pentagon on Tuesday.

“How do you explain a brother to somebody?” his sister Lucille Johnson of Evansville, Minnesota, wondered aloud Saturday. “He was very tall, not heavy but

good-sized, a good German boy. Very dedicated to his work.

“He was a very soft person, a very low-key person. He really enjoyed working with the retirees, making sure they got what they had coming and needed.

“We’ll all be there when it’s time,” Johnson said, speaking for the four of Beilke’s five surviving sisters. “We just hope they find his remains and put closure to this. That’s what we’re looking for now.”

Active in His Neighborhood

His neighbors in suburban Laurel, Maryland, remember Beilke as a quiet, friendly

man who never talked about his military experience. The kind of man who loved his flower beds and flourishing crepe myrtles, who audited the books of the homeowners association for free, saving his working-class neighbors $1,000 or so a year. The kind who kept doing so even after the association turned down his request to put a flagpole by the driveway.

The houses on Falling Waters Court are just 12 years old, and neighbor Lee Minton recalled that Beilke wasn’t happy about the “stick” trees. They were not big enough for squirrels, and he liked squirrels. So he put out nuts and food on his deck and the squirrels came running.

In fact, they would swarm out from the park behind Minton’s house, cross the street and scamper up Beilke’s driveway to get their meals. The squirrels would make a “daily passage,” Minton said, laughing.

It was Minton’s wife, Nancy, who figured out something was wrong when she saw a car belonging to one of the Beilkes’ daughters parked outside the house Wednesday. “She usually comes at the holidays. And then I saw some people in military uniform and I really got scared,” Nancy Minton said Saturday, blinking back tears.

She called Beilke’s wife, Lisa, and learned that he was one of those missing at the Pentagon–and feared dead.

Lisa Beilke “was extremely upset and extremely hopeful,” Nancy Minton said. “She said to me: ‘Max has a lot more living to do. We’ve got a lot more work in the yard to do, and a lot more traveling.’ ”

Nancy Minton prepared a note and put a copy in every mailbox on Falling Waters Court: “Dear Neighbors, I want to share some sad news with our community. Max Beilke, who works at the Pentagon, is listed as missing. Please keep Lisa, Joseph and the Beilke family in your thoughts and prayers.”

Beilke grew up in Alexandria, Minnesota, amid the corn and soybean farms west of

Minneapolis. His father drove a truck and worked for Land O’Lakes, the butter and cream company. The family lived on several acres outside of town–“a hobby farm,” they called it, not a big working farm like the ones that grew hundreds of acres of grain, fed beef cattle or produced milk.

He finished high school in 1950. He liked sports, but mostly “he liked being home on the farm with mom and dad,” his sister said.

In 1952, Beilke was drafted and later shipped out to Korea. He served his hitch and returned to civilian life. But something was missing. In 1956, he reenlisted, this time prepared to stay.

Beilke was approaching his 40th birthday and already a Master Sergeant with nearly 20 years’ service when he got to Vietnam in July, 1972. By then, the war was a savagely divisive conflict for Americans, and President Richard M. Nixon was edging out.

For eight months, Beilke served as operations sergeant at Saigon’s Camp Alpha, which processed all Army troops going in and out of the country. When the Paris peace accords were signed in 1973, the stage was set for his historic moment.

Among other things, the accords provided that all U.S. POWs would be released in Hanoi and all American troops would leave Vietnam by March 29, 1973–all but the Marine guards and military attaches at the U.S. Embassy, who were not counted as U.S. combat forces.

When the deadline arrived, Beilke said later: “I can remember a Colonel coming through the door and saying, ‘Beilke, they’re off the ground. They’re in the air at Hanoi. Let’s go home.’ That’s when we stamped the last orders and closed her up.”

Last Soldier Up the Ramp

The fall of Saigon to the North Vietnamese, and the desperate evacuation of the U.S Embassy, did not occur until April 29, 1975. But the official completion of the American troop withdrawal in 1973 was a major event. Beilke’s family back home watched it on television.

For many who boarded the last plane, it was a bitter experience. As agreed to in Paris, observers from the North Vietnamese army looked on, sometimes smiling and trying to shake hands with American officers. The gestures were largely ignored, or rebuffed with curses.

When Beilke started up the ramp, a North Vietnamese colonel stepped forward and presented him with a gift–a straw place mat decorated with the picture of a pagoda. Beilke, according to accounts at the time, looked down at the Colonel, accepted the gift and went on up the ramp.

“March 29 always sticks with me,” Beilke told an interviewer years later. “There are certain things–like your wedding anniversary, the day you came into the Army, the first time I left the country and shipped out for Korea in ’53–you remember those dates.”

His sister Lucille noted that it was after he came home from Vietnam that Beilke developed a passion for fishing. “It was the peacefulness of it,” she said.

With 21 years’ service completed, Beilke retired from the Army on November 1, 1974.

Once more, he worked at various jobs before finding a niche lobbying for active and retired military personnel.

In 1984, he returned to the Army as a civilian employee, focusing on the problems of Vietnam War veterans.

“I’ve always felt that we brought these young men out of Vietnam and discharged them from the Army and they lost their support group,” he said later. “When they went out into civilian life, and in some places a very hostile civilian life, it was tough for them to cope.”

“That’s what Max was there for. He traveled all across the country,” urging veterans to get help, his sister said.

There were unopened bags of mulch stacked at the top of Max Beilke’s driveway Saturday, but nobody was doing any yardwork.

“He was a very good neighbor and a very decent man,” Nancy Minton said. “I wish it all will have a happy ending, but I don’t think so.”

NOTE: Sergeant Beilke was laid to rest in Section 64 of Arlington National Cemetery, in the shadows of the Pentagon.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard