One of my personal HEROES

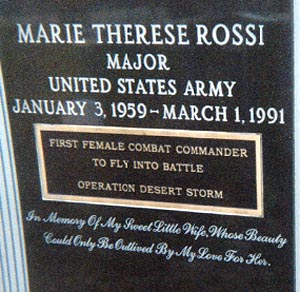

Major Rossi was one of the first US woman soldiers to participte in an air asault into enemy territory, she was killed when the Chinook helicopter that she was piloting crashed on March 1, 1991.

A native of Oradell, New Jersey, she served as a pilot with the 101st Airborne Division and led a squadron of Chinook helicopters 50 miles inside Iraq during operation Desert Storm on February 24, 1991, ferrying fuel and ammunition during the very first hours of the ground assault.

At the time of her death she was married to Chief Warrant Officer John Anderson Cayton, who was also serving as a pilot in the Gulf. Marie was interviewed by CNN just days before her death and said, “Sometimes you have to disassociate how I feel Personally about the prospect of going into war and, you know, possibly see the death that’s going to be there. But personally, as an aviator and a soldier, thi

s is the moment that everybody trains for – that I’ve trained for – so I feel ready to meet the challenge. I don’t necessarily personally like it; if I had the opportunity and they called a ceasefire tomorrow that would be great.”

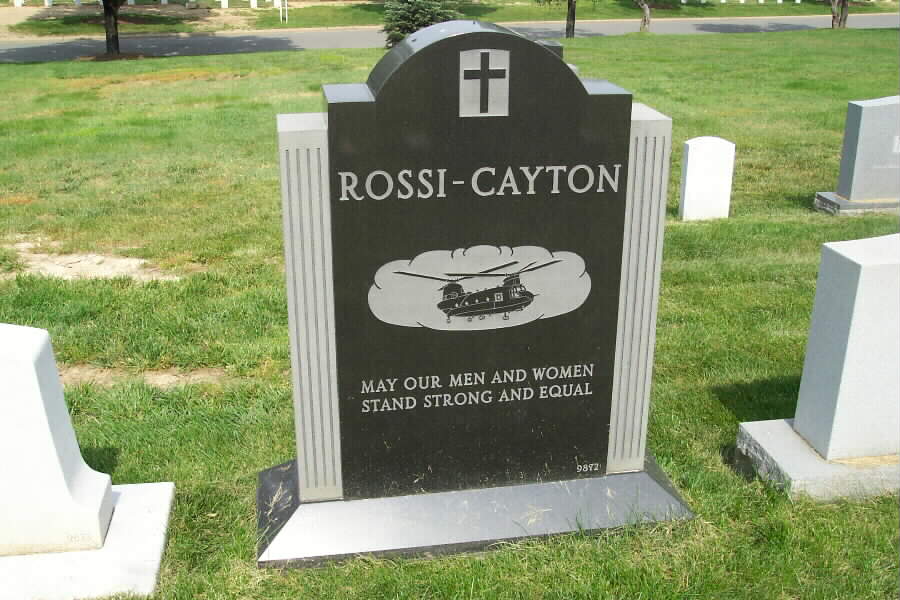

She was buried in Section 8 of Arlington National Cemetery on March 11, 1991. Truly this young woman was an American Hero!

April 21, 1991 – Hers: Requiem for a Soldier

The American flag was draped over the gunmetal-gray coffin at a funeral home in Oradell, N.J. On a table to the left of the coffin was an 8-by-10 photo of a smiling, somewhat shy-looking woman wearing a soft pastel suit and pearls. On the right was quite another photograph, of a leaner-faced woman with a cocky grin, hands on the hips of her desert camouflage uniform, an Army helicopter of the Second Battalion, 159th Aviation immediately behind her.

I drove three hours to Maj. Marie T. Rossi’s wake and returned the next day for her funeral. I’d never met the chopper pilot whose helicopter had hit a microwave tower near a Saudi pipeline, the commanding officer of Company B who’d clung to civilized living in the desert by laying a “parquet” floor of half-filled sandbags in her tent, the woman who, after Sunday services, invited the chaplain back to share the Earl Grey tea her mother had sent her.

I was planning to interview Major Rossi when she returned to the States, to try to understand why she and so many other bright and thoughtful women were choosing careers in the military. Like many other civilians, I had been stunned to learn the numbers of women serving in the armed forces. If there hadn’t been a war, I never would have known. Because there’d been a war, I’d now never know Major Rossi.

Watching the war on television, I’d vacillated between feelings of awe and uneasiness at women in their modern military roles. It was jolting to see young women loading missiles on planes and aching to fly fighter jets in combat. On the other hand, I admired these military women for driving six-wheel trucks and shinnying in and out of jet engine pods. A final barrier seemed to be breaking down between the sexes. But at what cost? Looking at the military funeral detachment as it wheeled Major Rossi’s coffin into St. Joseph’s Church, I tried to summon up pride for a fallen soldier, but instead felt sadness for a fallen sister.

As Major Rossi’s friends and relatives spoke, I recalled an August evening soon after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait when my daughters were home on vacation and several of their male friends dropped by. The young men, juniors and seniors in college, were pale and strained, talking anxiously about the possibility of a military draft. My daughters, 19 and 21 years old, were chattering on about their hopes for interesting jobs after graduation. It hadn’t seemed fair. Here were my girls — healthy, strong graduates of Outward Bound, their faces still flushed from a pre-dinner run — talking freely about the future. And here were the boys whose futures suddenly seemed threatened.

I didn’t know what to think. I still don’t. As a feminist and my own sort of patriot, I feel that women and men should share equally in the burdens and the opportunities of citizenship. But the new military seems to have stretched equality to the breaking point. The surreal live television hookup between a family in the States and a mother in the desert reminding them where the Christmas ornaments were stored smacked of values gone entirely awry. Yet this woman, like the 29,000 others in the gulf, had voluntarily signed on to serve. What siren song had the military sung to them?

To ground myself in this growing phenomenon, I’d taken my younger daughter to a recruiting station in Riverhead, L.I. Each branch of the military had an office — the Army, the Navy, the Air Force, the Marines. The recruiters were very persuasive. “When you graduate, do you think any employer is going to be banging on your door in this economy?” the Marine recruiter asked her. “Think about it. You’re out of college. Your Mom breaks your plate. Your Dad turns your bedroom into a den. You’re on your own. Now what do you do?” He gave me a decal: “My daughter is a United States Marine.”

The Air Force recruiter was easier to resist. “Have you ever had problems with the law?” he grilled my daughter. “Have you ever been arrested, ever gotten a traffic ticket? Have you ever sold, bought, trafficked, brought drugs into the country, used drugs?” Instead of a decal, he gave us a copy of “High Flight,” the romantic World War II poem President Reagan had used to eulogize the crew of the Challenger. “Oh, I have slipped the surly bonds of earth and danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings” it begins. The Air Force recruiter did not mention the fact that the poem’s author, John Gillespie Magee Jr., had died in the war at the age of 19.

There is no talk of death in recruiting offices, no talk of danger or war or separation from families. The operative words are “opportunity,” “education,” “technical skills” and “training.” The Marine recruiter added another military carrot by pulling out a sheet of paper with newspaper want ads Scotch-taped to it. “Every job opening requires skills. But how do you get them? We give them to you.” My daughter’s face began to flush. “If we don’t get out of here in 30 seconds, I’m going to sign up,” she muttered.

Those in the military know about death, of course. They get on-the-job training. Major Rossi’s husband, Chief Warrant Officer John Anderson Cayton, told the mourners at her funeral that he had prayed hard for his wife’s safety while he was serving in Kuwait. His were not the prayers that come on Hallmark cards. “I prayed that guidance be given to her so that she could command the company, so she could lead her troops in battle,” said the tall young man in the same dress blue Army uniform he’d worn to their wedding just nine months before. “And I prayed to the Lord to take care of my sweet little wife.”

Habits fade away slowly, just like old soldiers. When I called Arlington National Cemetery to confirm the time of Major Rossi’s burial, I was told “he” was down for 3 P.M. on March 11.

“She,” I corrected the scheduler gently.

“His family and friends will gather at the new administration building,” the scheduler continued.

“Her family and friends,” I said more firmly. “Major Rossi is a woman.”

“Be here at least 15 minutes early,” she said. “We have a lot of burials on Monday.”

Hundreds of military women turned out at Arlington, wearing stripes and ribbons and badges indecipherable to most civilians. I caught a ride with three members of the Women Auxiliary Service Pilots, the Wasps, who flew during World War II. One was wearing her husband’s shirt under her old uniform. The shirts sold at the PX with narrow enough shoulders, she explained, don’t fit over the bust.

No one knows how many women are buried in their own military right under the 220,000 pristine headstones at Arlington. The cemetery’s records do not differentiate between genders or among races and religions.

“If the women were married, you could walk around and count the headstones that say ‘Her husband,’ rather than ‘His wife,’ ” suggested an Arlington historian. “I’ve seen a few and always noticed them.” Arlington is going to run out of room by the year 2035; a columbarium will provide 100,000 niches for the ashes of 21st century soldiers. How many of them will be women?

The military pageant of death, no doubt, will remain the same. Six black horses pulled the caisson carrying Major Rossi’s coffin. Seven riflemen fired the 21-gun salute, the band softly played “America the Beautiful” and a solitary bugler under the trees blew taps. Major Rossi’s husband threw the first spadeful of dirt on his wife’s coffin, her brother, the second. It was a scene we’re going to have get used to in this new military of ours, as we bury our sisters, our mothers, our wives, our daughters.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard