13 June 2006

THREE RIVERS, Texas – A soldier whose burial some 60 years ago became a symbol of Mexican-American civil rights will be remembered with a historical roadside marker.

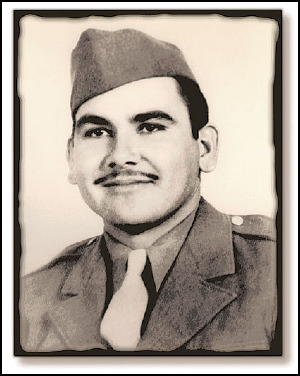

The Texas Historical Commission unanimously approved the marker on June 9, 2006, for Private Felix Z. Longoria. The Three Rivers soldier was killed in action in the Philippines in 1945.

According to his family, a funeral home in the South Texas town refused to hold his funeral services because he was Hispanic. Many in town dispute this, saying a wake was refused because of a disagreement in the Longoria family.

Dr. Hector P. Garcia, who founded the American G.I. Forum, and then-U.S. Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas intervened, and Longoria was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Santiago Hernandez, of a local G.I. Forum, led the effort to get the marker, saying the incident became a catalyst for other civil rights issues. Hernandez is working to get the Three Rivers post office renamed in Longoria’s honor, but the issue has stalled in Congress.

Texas town remains divided over WWII-era racial dispute

Controversy is re-ignited by move to rename post office for Latino soldier

By Lianne Hart

Courtesy of the Los Angeles Times

Originally published June 27, 2004

THREE RIVERS, Texas – Four years after he died in combat during World War II, Private Felix Longoria’s body was taken from a temporary grave in the Philippines and shipped home to South Texas.

His widow, Beatrice, went to the town’s only funeral home and asked the owner, Tom Kennedy, to open the chapel for the wake. What happened next is so disputed that a recent move to honor the soldier’s memory has renewed a 55-year-old quarrel and set the town on edge.

“You cannot imagine the stir this has caused,” said Patty Reagan, a resident and Kennedy family friend. “All the old wounds have been reopened.”

At the center of the dispute was the Rice Funeral Home. Its chapel was open to whites, but its availability to the town’s Latinos – such as the Longorias – was unclear.

According to Beatrice Longoria, Kennedy denied chapel services for her husband because “the whites won’t like it.” Kennedy contended that he merely asked Longoria to hold the wake in her home to avoid a public scene with what he described as her estranged in-laws.

What followed were six weeks of turmoil, the intervention of then-Senator Lyndon B. Johnson and a hard-to-shake reputation for racism in the town.

Historians say the incident helped unify Latinos and bring national attention to the Mexican-American civil rights movement. But many residents believe political opportunists twisted the words of a good man to advance a cause.

This town of 1,805 at the juncture of three rivers between Corpus Christi and San Antonio bills itself as a fishing and hunting spot. Early in the 1900s, it had a glass factory and a natural gas refinery. Like many towns, it had separate cemeteries for whites and Latinos.

The power of the funeral controversy surfaced at a recent City Council meeting – a tense, standing-room-only affair addressing a proposal to rename the post office after Longoria.

Carolina Quintanilla, Longoria’s sister, and Susan Zamzow, Kennedy’s daughter, were there as it became clear that more than the name of a post office was at stake and the emotions had cooled very little.

Felix Longoria was a truck driver, married and the father of a young daughter when his draft papers arrived in 1944. Seven months later, at age 25, he was killed by enemy fire on the island of Luzon.

His wife, Beatrice, was young, shy and unlikely to seek the spotlight, her relatives say. But when the funeral home refused chapel services, she let her sister call Hector Garcia, a surgeon from Corpus Christi who had founded the American GI Forum, a civil rights organization.

Documents archived at Texas A&M University detail how events unfolded, starting with a call from Garcia to Kennedy about the wake. Garcia’s secretary, Gladys Bucher, listened in and took notes.

Kennedy, who was white, said that “it doesn’t make any difference” that Longoria was a veteran, according to Bucher’s notes. “You know how the Latin people get drunk and lay around all the time. The last time we let them use the chapel, they got all drunk and we just can’t control them – so the white people object to it, and we just can’t let them use it.”

Garcia then contacted a local reporter, George Groh, who also called Kennedy. “We never made a practice of letting Mexicans use the chapel,” Kennedy was said to have told Groh, “and we don’t want to start now.”

Garcia organized a protest – more than 1,000 people attended – and the national media descended. Faced with a public relations mess, city leaders said “outsiders” such as Garcia had distorted the truth. The Chamber of Commerce adopted a resolution deploring “misconstrued” facts that “grossly misrepresented” the town.

Kennedy told his version of the story in the Three Rivers newspaper. He had heard of a conflict between Beatrice Longoria and her in-laws, he said, and worried “there may be some trouble at the funeral service.” That’s why he asked Longoria to hold the wake at her house, he said: “I did not at any time refuse to bury him or allow the use of the chapel because he was Latin American.”

As the claims and counterclaims flew, Lyndon Johnson sent a telegram to Garcia, offering to arrange a burial for Longoria at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. The next day, Kennedy sent a letter to Beatrice Longoria offering use of his chapel. “We are only too glad to be of service,” it read.

Longoria was buried at Arlington as his family, Johnson and Lady Bird Johnson stood under a gray February sky.

Longoria’s story faded elsewhere, but in Texas the memories remained. Two years ago, Santiago Hernandez, a federal prison guard from Corpus Christi, began a campaign to rename the Three Rivers post office.

In February, Democratic Rep. Lloyd Doggett of Texas said he would put the proposal before Congress if residents supported it. Which is why City Hall was packed last month as the City Council considered the idea.

After listening to residents and deliberating, the council announced it would not oppose renaming the post office to honor Longoria’s service.

Longoria’s sister stepped outside the building and wept. “I’m hoping and praying that it will all end now. I believe this is it,” she said.

Zamzow also wiped tears from her eyes, but had no comment. Reagan has begun a letter-writing campaign to let Doggett know that “local people don’t want this,” she said. “We like the name the way it is.”

Stuck in the past

Town forced to revisit purported racist history

By Brad Olson Caller-Times

April 12, 2004THREE RIVERS, TEXAS – The questions, they say, always come from outsiders. “Is this the place where they don’t bury Mexicans?” the outsiders ask. Or, “Do you know what happened to Felix Longoria?”

If it were up to people in Three Rivers, “this whole thing,” as it is often referred to, would go away. Three Rivers is a nice town, they say, a color-blind town. Prominent Anglos and Hispanics here believe the incident is just an open wound that needs to be closed.

But every now and then, someone comes in – maybe a student, maybe a tourist, maybe a reporter – and brings it up again.

This time, the “outsider” is a correctional officer who works at the federal prison just outside the city. Mostly, when people come to ask questions, they get their answers and leave. But Corpus Christi resident Santiago Hernandez is not going away. He’s trying to convince people in the city to rename the local post office after Private Felix Z. Longoria, in recognition of the event that became what many say was the Rosa Parks moment of the Mexican-American civil rights movement.

The subject of renaming the post office has caused numerous city officials a great deal of uneasiness, including the town’s newly elected and first Hispanic mayor, whose feelings about the controversy are riddled with ambivalence.

It’s been 55 years since Longoria’s wife, Beatrice, was refused a wake service for her husband because the local funeral home director believed “the whites would not like it.”

Longoria was killed by a Japanese sniper in World War II in the Philippines and his remains were finally brought home in 1949.

The controversy that followed polarized the town, and Three Rivers has been a byword for discrimination and intolerance in some quarters ever since.

Almost in a reactive way, people in Three Rivers – whether Anglo or Hispanic – still appear agitated with the impact of one event on the town’s historical legacy, and largely uncomfortable with the city’s racist past. Some deny it even has one. And as for the Longoria incident, many seem to recall a different set of events.

A pivotal moment, invisible

The story is a simple one. A young, Hispanic widow asked to have a service for her husband in the funeral home chapel run by Tom Kennedy, and she was refused because of her race. Such things were common then. Those were the times. Worse cases of racism occurred every day. This time, though, would be different.

Dr. Hector P. Garcia, who led a newly formed Mexican-American veterans advocacy group called the G.I. Forum, joined the fight and recruited Lyndon B. Johnson, a newly elected U.S. senator from Texas. Johnson offered to bury Longoria at Arlington National Cemetery, home to the military’s heroes and luminaries, where he eventually was laid to rest February 16, 1949.

Because of the event, the G.I. Forum, with Garcia as its leader, became a leading Mexican-American civil rights organization. Patrick Carroll, a Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi history professor who wrote a book on the subject, said the Longoria affair was a pivotal moment in Mexican-American history. Once people knew Longoria’s story, they began to distinguish between Mexican-Americans and Mexican nationals as well as regard Mexican-Americans as patriots, since Longoria had died fighting in World War II.

With the story’s telling and re-telling, as well as Hernandez’s prodding, the subject has begun to roil through Three Rivers again. But roving through the town – population 1,878 – one never would know this happened here. Felix Longoria isn’t mentioned anywhere. His story is not mentioned in any of the schools. A Three Rivers High School history teacher who asked not to be identified and who grew up in Three Rivers, said she had never heard of the affair. The high school doesn’t teach about it – it follows state curriculum.

Making history

Since the post office is a federal building, renaming it would require a bill to pass through Congress, something Hernandez said he has discussed with U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett, D-Austin. Because of congressional redistricting, Doggett currently is running in District 25, which includes Three Rivers. Hernandez said Doggett promised to introduce a bill to rename the post office if there was local support for the measure. Doggett’s chief of staff did not return phone calls.

Once he secured the promise from Doggett, Hernandez began to collect letters of support from family members, lawmakers and political organizations to bolster the cause. He also wrote a resolution he plans to bring before the Three Rivers City Council today.

Much like Lyndon Johnson has been accused of political opportunism for his moves to secure civil rights for minorities, townspeople have accused Hernandez of ulterior motives – such as his candidacy for the Corpus Christi Independent School District Board of Trustees – something he adamantly denies.

Facing opposition

Although a petition circulating throughout the community has received numerous signatures, Hernandez faces significant opposition to the resolution, most particularly from Three Rivers Mayor Felipe Martinez.

“My feeling when he approached me with this was ‘Do we need to do this right now, now that I became mayor?’ ” Martinez said. “Why didn’t they do it before? It happened in 1949.”

Martinez and his wife, Lupe, believe he is being exploited.

Hernandez denies his timing has anything to do with Martinez’s ethnicity, and says he is motivated only by his convictions about education and history.

“People say ‘You can make history,’ ” Martinez said. “I don’t care about making history. I’m not there for a popularity contest or anything else. I’m here to help the people. I’m not talking about just Hispanics, I’m talking about all races.”

Martinez said he is worried the post office proposal will divide the city, since about half the population is Anglo and half is Hispanic. Sammy Garcia, a Three Rivers city councilman, expressed similar concerns.

“We’re just trying to understand this and hope the good Lord should give us an answer as to how to handle this,” Martinez said.

Perceptions of the conflict in Three Rivers are divided along racial lines. Many Anglos in the city hold to Tom Kennedy’s side of the story, or at least those who have heard it.

“History is full of holes, and there are large holes here in this story,” said Tom House, Tom Kennedy’s grandson.

Jane Kennedy, Tom Kennedy’s wife, would not be interviewed for this story. But when interviewed by Carroll for his book, “Felix Longoria’s Wake,” she presented the same version of the event her husband told until he died: his refusal was based on a desire to avoid a family scuffle that had unfolded between Beatrice Longoria and her husband’s parents. It had nothing to do with race.

Carroll said Tom Kennedy’s version of the story was contradicted by evidence from various sources.

“The evidence overwhelmingly suggests, from independent sources, that the primary motive behind denying use of the funeral chapel was racist or ethnocentric in nature,” Carroll said. “Tom Kennedy had said as much in four different conversations with four different people.”

Testified to racism

Five witnesses either testified under oath or made notarized statements affirming Kennedy’s motive was racially based, according to Carroll’s book and supporting documentation.

As the controversy heated up, Anglos in Three Rivers began to organize a campaign to counteract the efforts by Garcia and Johnson. On one occasion, the mayor, head of the chamber of commerce and the Three Rivers bank president, along with Kennedy, all tried to pressure Longoria’s father to sign a statement upholding Kennedy’s story.

But Guadalupe Longoria Sr. refused to sign it and eventually ripped up the document. The statement was released to the media anyway. In a politically charged Texas legislative hearing, lawmakers eventually cleared Kennedy of any wrongdoing. But the hearing’s findings largely ignored available evidence, according to Carroll’s book.

“Putting it in context, that became the explanation that the Anglo population seized upon in justifying Tom Kennedy’s actions,” Carroll said.

Regardless of whether the event actually occurred, this long has been a terrible ordeal for the Kennedy family, one they regard with caution and fear. Susan Zamzow, Kennedy’s daughter, and House were reluctant to be interviewed for the story for fear of retribution.

Zamzow still recalls reading the letters strangers sent her family after the incident.

“After all this started, they (the letter writers) threatened to kill the whole family and they threatened to kidnap me,” she said. “Another letter said they’d kill me.”

When Three Rivers was overrun by a devastating flood in 1967, all the letters were destroyed. Her mother had kept them all, along with newspaper clippings from papers all over the country, Zamzow said.

Carroll said in his book the Kennedys also were victims in this story, and that Tom Kennedy never recovered from the event.

“No one suffered from the incident more than he did,” Carroll writes. “Outsiders attacked him and his family mercilessly . . . The abuse far exceeded any crime he might have committed.”

Not everyone is opposed to renaming the post office, despite their resentment of the event’s effect on Three Rivers and their own lives.

Zamzow and House have said they would support the measure, so long as it was not relative to the burial controversy, but a celebration of Longoria’s heroism in the war. In a sign of a probable compromise that will emerge tonight, City Councilman Sammy Garcia agreed.

“As far as naming the post office after him for what he did in the war, that’s wonderful,” Garcia said.

Zamzow said: “There’s no problem with that. My father, he understood about it. Especially somebody being in the war, he would want to give another soldier a proper burial.”

House and Sammy Garcia said the incident has hurt many people in town, but they knew the success and rise to prominence of the G.I. Forum has been at least one positive result.

Felix Longoria’s sister, Carolina G. Quintanilla, who served four terms on the Three Rivers City Council, said she was fairly certain the measure would pass.

“Oh, yes, it’s going to go through,” she said. “And they’re going to raise hell when it does.”

Quintanilla said one resident warned her the measure could ruin the town.

“I said, ‘What’s so good about the town?’ ” Quintanilla said. “Nothing’s going to change around here. You’re just a Mexican and you are what you are.”

Since the incident, people have called her family from cities all over the East Coast and asked permission to name streets after her brother. No one from Three Rivers has made such a request.

Another option

Quintanilla admitted relations in the town between Hispanics and Anglos had improved over the years. One reason she saw was job availability at the refinery, but another, more significant sign for her is mixed marriage. Martinez agreed, citing the marriages of his two sons.

Other signs confirm that things have improved.

Another of Longoria’s sisters now harmoniously lives three houses away from Jane Kennedy. House is close friends with Sammy Garcia, who is also related to the Longorias.

Mayor Martinez said he would like to recognize Longoria because of the legacy this event carries with Hispanics but would do what was best for Three Rivers. He doesn’t know what people in the community will say, but he plans to allow Hernandez to speak at the meeting tonight.

Patty Reagan, who owns a shop next door to the old funeral home chapel, said she was unsure about naming the post office after Longoria.

“I just don’t know that we’d want to memorialize a situation that’s unclear,” she said. “I might rename it Ms. Thelma Bomer because she was just this real sweet woman everybody loved here in town. If I were going to rename it, I would name it after her instead of something controversial.”

How a dead hero changed our lives

April 27, 2003

Courtsy of the Corpus Christi Caller TimesIt may be difficult now to grasp how the Felix Longoria episode, which took place in 1949, came to have such an impact.

The refusal by a Three Rivers funeral home to handle the burial of a Mexican-American soldier killed in battle became a turning point in the history of South Texas. It made Dr. Hector P. Garcia a national civil rights leader, boosted the political career of Lyndon B. Johnson, and gave Longoria a place in history that he would likely have never achieved in life.

Instead of being forgotten in a small-town cemetery, Longoria was buried in the resting place of American heroes – Arlington National Cemetery.

Understanding South Texas in those post-war years, the place that Mexican-Americans and Anglos had in it, and how Garcia began to transform how others saw that relationship, is the gist of a new book, “Felix Longoria’s Wake,” by Patrick J. Carroll, who teaches history at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi.

Years ago, as a graduate student, I sat in Pat Carroll’s class and heard him expound on the need to explore an issue in the context of SPEED, an acronym; that is, issues should be examined in their social, political, economic, ecological and demographic aspects. He has followed his own advice magnificently.

At the moment, on Jan. 7, 1949, when Beatrice Longoria met with the operators of the Manor Rice Funeral Home in Three Rivers to arrange for the burial of her dead soldier husband, an entire history of a region and a people was changing. The old paternalistic relationship between ranch barons and vaqueros was fading into the mist. A vast migration from Mexico in the early third of the century had redefined the place of what had been a much smaller Tejano population, that is a native Hispanic population, both in its own eyes and those of the economically dominant Anglo population. And the Anglo population itself was changing; the onset of irrigation farming had lured more Midwesterners to the region.

What had been a ranching culture where Spanish was spoken as often, or more, than English, and an apparent, if not real, egalitarianism of the saddle was changing to an impersonal, harsher relationship of Anglo employer and Mexican employee. And the word was Mexican, for as Carroll argues, the distinction between native-born and immigrant was lost.

The particular geographical focus of this change was what Carroll calls the “Nueces strip,” the area stretching from the Rio Grande Valley to just north of Three Rivers. As Carroll argues, the way the Longoria incident occurred and its ramifications could have only happened at that time and that place.

Carroll gives new meaning to the role played by Beatrice Longoria, who had the courage to refuse to submit to this insult, breaking out of a cultural mold. Her husband had died wearing the uniform of the United States and yet he was still seen in an inferior light in his hometown.

The irony is that Tom Kennedy, the funeral home owner, had himself been a soldier, had fought in Europe and had been wounded. Longoria had been killed by a sniper in the Philippines. But though they were linked by a common experience, Longoria and Kennedy were divided by the bright line of discrimination that ran through every South Texas town. When he turned Longoria down because “the whites wouldn’t like it,” he was simply reflecting a shared attitude.

Some might ask, why resurrect memories that can only nurse resentment? I think it’s important because we are still accommodating ourselves to the transfer of political power to Hispanics, still struggling to raise educational levels for all children, and still haunted by the ghosts of our past. Just like the Anglos who couldn’t understand all the fuss, and the Mexican-Americans who saw every mean slight and racial slur in Longoria’s shunned corpse, our understanding of ourselves is as much emotion as it is reason. The role of history is to tell us who we are and how we came to be. “Felix Longoria’s Wake” is an important part of that story.

Sarah Moreno Posas,

Sister-In-Law of Felix Longoria

Copyright 2002 South Texas Public Broadcasting System, INC.Q: What were some of the obvious signs of discrimination you and your sister noticed growing up in Three Rivers?

A: What was obvious about, discrimination in Three Rivers was, we were not allowed to go to the first floor in the movies. We had to go upstairs. There were restaurants that did not allow Hispanics. And, my older sisters worked, cleaning houses for the Anglo people and, I remember one instance where one of the ladies that my sister worked for cleaning the house one day saw me and she said, “Oh, here. Take this to Beatrice.” And it was 15 cents, 15 cents for cleaning her house the whole day. And, things like that that to me sounded so unjust. As young as I was, I knew it wasn’t right.

Q: What did your father do for a living?

A: My father worked for the railroad and he was a foreman. They did repairs of the railroad tracks, and one-day his engine where he transported his workers to the sites was caught by a train and damaged, demolished. And so he was dismissed and so there was nothing else to do in Three Rivers so he decided to buy a truck and, uh, go to different places to work. And so he took some people, migrants, and just kind of followed the crops.

And I remember one time that we went somewhere in West Texas, it being so cold… at the time and I remember sleeping in-in barns. They had no housing for the workers. So we slept wherever we could find a place. And, after a few months, after them finishing the work around there, we started back home and it was also very, very cold. I remember we were all riding in the back of the truck. And it was late at night and we were quite a distance from getting home, so my mother insisted that we stop and rent a place to sleep and rest and get out of the cold. Well, my dad stopped at the first town that we came to, and he approached a little motel and asked if they had a place for us and he said, they told him that they didn’t allow Mexicans. And so he came and got on the truck and just continued on, and drove on until we got home in the early hours of the morning, and in the freezing rain and cold and that… really hurt. (Begins to cry) Oh, that… that’s painful, even after so many years… when I remember those times it hurts.

Q: I’d like you to discuss the incident dealing with your brother-in-law and your sister. Maybe you can just kind of paint a little biographical picture of Felix Longoria,, his family and what he was doing before he was drafted.

A: Well, Felix Longoria was a young husband and father, a very wonderful son-in-law to my parents. When he was around our home he helped my parents fix anything that needed fixing and he was a very caring and loving young man. I loved him dearly and– so they moved to Corpus Christi from Three Rivers because, as I say, there was nothing that he could make a living to support his wife and child. So he moved to the big city and he got a job as a truck driver. And it was a short while later that he was called to, serve his country. And, so he very willing left, went to basic training for about six months and, I think, he came to visit one time. And, then he left, to California and from there he was shipped to the Pacific, to the Philippine Islands. And that was the last time that we, saw him, because the next thing that happened was, we– my sister was notified that he died in action just a month after he had, left the United States.

Q: Would you tell us the story of the actual incident regarding Dr. Garcia and his participation in this incident which begins when you overhear the conversation between your sister and your parents?.

A: Right after the end of the World War, my sister was notified that he had died in action, and to wait for further instructions whenever his body would be returned for burial. So it wasn’t until 1948, the bodies of the soldiers were being returned to the United States for burial to their families. So my sister received notice that, she needed to make arrangements at a funeral home, local funeral home, to receive the body when it arrived. And so she, took a trip by bus to Three Rivers, which is just about an hour and half from Corpus Christi, and she went and approached the funeral home, and have his body returned there for a wake and for service. Well, to her dismay the owner said, “I’m sorry, but the whites would object… because Mexicans are not served here.” And, so my sister came home and when she was sharing that with my parents, she was very frustrated because she didn’t know what to do next. She was kind of confused. And, I overheard her telling my parents that.

Q: Was she willing to accept this?

A: Well, she really was confused as to what to do next. And when I overheard her sharing that, and about not knowing what to do next, I immediately walked up and I said, “Well, would you like to, call someone that can probably do something about it?” And so she said, “Yes.” Because the first thought that came to me was calling Dr. Hector Garcia. So she said, “Yeah, uh, would you– can you call?” And so I got on the phone immediately and that’s all it took, a call to Dr. Hector Garcia.

He called the right people and, so, consequently the whole world– in a weeks time, my sister was receiving, correspondence from all over the United States and even outside the United States, condemning, the situation. And offers of places where he could be given a decent burial. And one of those offers was from the then Senator Lyndon Johnson who offered to have him buried anywhere that the widow wished, including the Arlington National Cemetery.

Q: Now, your family didn’t have the resources, financially, to be able to go to Washington, D.C.. Can you tell me about the effort and what took place in order to ensure that the family members could go?

A: Yes, that’s another thing, that Dr. Garcia saw to it that the family would be able to attend the funeral. And so, they passed the hat around at that meeting and then they opened it to, anyone that wished to send donations for the, family members to attend the funeral in Washington. And so, it was overwhelming, everybody, all the family– His family was able to attend the funeral, his mother and sister and brothers. And, Senator Lyndon Johnson and Lady Bird were there at the funeral along with a representative that, President Truman – General Vaughan was his name. He came to represent the President. I remember there was a military band playing and I remember very well one of the numbers that was played was “Onward Christian Soldiers”, which reminds me of that funeral all the time that I hear it.

Q: How did things change for you after this incident?

A: I got involved– right after the funeral, I got more involved in the, Ladies Auxiliary of the G. I. Forum because I realized that so much work needed to be done. And, I joined along with other members, in going all over Texas to organize new chapters of the G. I. Forum. And, I also participated in going and urging people to buy their voters registration because they had to buy it.

Q: You did tell us about visiting Dr. Garcia in the hospital in his last days. And I know that’s tough to talk about, but I wondered if you could just share with us a little bit about getting to see him again in those final days.

A: Yes, I visited Dr. Garcia when he was in his last days on this earth. He suffered with cancer, and I had the opportunity to visit him just a couple of days before he died. And I went in and hugged him and I told him how much I loved him, and how much my family was grateful to him for all that he had done for us and how much I respected him. And that was good feeling and I felt sad that a legend that was about to leave us on this earth. But, I know that he heard me. He was a man that made a difference to so many people.

And even today, I feel challenged every time I turn around, when I hear racist remarks and, people being indifferent, intolerant towards other people of different colors. And I have learned to speak out in a loving way, and let people know that that is not right. So, I remember Dr. Garcia, every time that a situation comes up and I speak up. I can feel his presence. I feel that he’s my angel.

From a contrmporary press report:Hector Garcia, 82, a Texas physician who led the fight for equal treatment of Hispanics and who founded the American GI Forum in 1948, died of pneumonia July 26, 1996 at a hospital here. He had cancer and congestive heart failure. Dr. Garcia, who was known as “Dr.Hector,” practiced medicine in Corpus Christi for 50 years before closing his office in March.

In 1948, he founded the American GI Forum to fight for Hispanic veterans’ rights. In 1949, the forum gained nationwide recognition when it took up the plight of Felix Longoria, a soldier whose remains were returned from Luzon, in the Philippines, for burial four years after World War II ended. His hometown funeral home in Three Rivers, Tex., refused to let the family use its chapel because he was Mexican American, saying that “the Anglo people would not stand for it.”

Longoria’s story ran on the Associated Press wire, and within days, the case drew ire nationwide. Then-Senator Lyndon B.Johnson (D-Texas)intervened, and Longoria was buried in Arlington National Cemetery Section 34). Under Dr. Garcia’s leadership, the GI Forum expanded its focus to fight discrimination in other areas, including courts and schools.

From a press report: December 1997:

When Felix Longoria was growing up in Three Rivers, Texas, a barbed wire fence divided the town cemetery into two parts — one for Whites and one for those called ‘Mexicans’ despite their U.S. citizenship. In small towns all along the border, signs in shop windows declared ‘No Mexicans.’ Mexican-American tax dollars supported ‘White Only’ swimming pools. For many young men like Felix Longoria, job discrimination closed the door on a brighter future. It wasn’t until he joined the Army in 1945 that Felix experienced the full equality of his citizenship. Unlike their African-American counterparts, Mexican-American servicemen were not segregated from the majority.

“On June 15, 1945, while scouting for enemy positions in a jungle of the Philippines, Felix was struck by a Japanese sniper’s bullet and killed instantly. Back in Three Rivers, his widow Beatrice and their little girl waited three years for word that his remains were being transported home for a proper burial. She arranged to have his wake held at the local mortuary rather than in her own living room, as was the Mexican custom.

“Just before the train arrived, the owner of Rice Funeral Home told Beatrice that she would have to change her plans. The establishment couldn’t provide its chapel service for the Longorias after all, he said, ‘because the Whites would not like it.’

“The broken promise doubled Beatrice’s grief. She could scarcely believe that fellow Americans, whom Felix had died to protect, still viewed him as a second-class citizen. Quickly, her pain gave rise to anger, and then to action. Beatrice and her family resolved that the world outside Three Rivers should hear their story.

“Through a veterans’ organization in Corpus Christi, the news reached Washington. During a protest meeting at Three Rivers, a courier delivered a message from U.S. Sen. Lyndon Johnson of Texas: ‘I have today made arrangements to have Felix Longoria reburied with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery … where the honored dead of our nation’s wars rest.’

“The funeral took place on Feb. 16, 1949, as a gray drizzle shrouded the gentle slopes of Arlington. Felix’s whole family was there. Sen. Johnson and his wife came to pay their respects. Mexican diplomats brought flowers in tribute from their country.

“A state legislative investigation initially concluded that no racial discrimination had occurred against Beatrice Longoria, but members later called the report into question and it was withdrawn. Felix’s burial at Arlington reversed one glaring injustice, but, even for his family, it didn’t provide all the answers. Years later, his sister-in-law still asked herself, ‘Why should I have to come so many miles away to this cemetery? How many Felix Longoria cases must have gone unheard of?”‘

I don’t know how many cases like this went unheard. If there was even one more, and I’m sure there was, it was one too many. The living heroes of this story must include Beatrice Longoria and then-Sen. Lyndon Johnson. She had the courage to challenge bigotry and he had the compassion and strength to right a wrong.

December 12, 1997

Where I Stand–Mike O’Callaghan:

Gelix Longoria’s burial in Arlington National Cemetery

MIKE O’CALLAGHAN is executive editor of the Las Vegas SUN.

SEVERAL RECENT HAPPENINGS have made me think about some past experiences. The gathering of Hispanics at UNLV reminded me of my pal and squad leader Johnny Estrada, who was killed by fragments from the mortar shell which scored a direct hit on me. Johnny had been wounded earlier in the day and, after getting sewed up at an aid station, he returned to help us hold our position. That’s the kind of man he was at the age of 18.

Later, I returned to California to visit his family of Mexican-American field workers. Almost five months after he was killed, they had yet to receive his six-months gratuity pay from the Army and the Veterans Administration hadn’t made arrangements for their insurance payments. Things didn’t get any better until I went with them to the VA office in Tulare. About the only thing that went right for the Estrada family was Johnny’s burial.

This is more than can be said for Felix Longoria a few years earlier. Today, we argue about who can or can’t be buried in Arlington National Cemetery, where Felix is now buried. The inappropriate burial of a former U.S. ambassador at Arlington has resulted in his body being removed from that hallowed ground.

Teaching Tolerance is a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, which concentrates on teaching Americans to appreciate each other no matter what our individual differences. One story told by that project reminds me of the good and bad and past and present history of a country made great by men like Johnny Estrada and Felix Longoria.

“When Felix Longoria was growing up in Three Rivers, Texas, a barbed wire fence divided the town cemetery into two parts — one for Whites and one for those called ‘Mexicans’ despite their U.S. citizenship. In small towns all along the border, signs in shop windows declared ‘No Mexicans.’ Mexican-American tax dollars supported ‘White Only’ swimming pools. For many young men like Felix Longoria, job discrimination closed the door on a brighter future. It wasn’t until he joined the Army in 1945 that Felix experienced the full equality of his citizenship. Unlike their African-American counterparts, Mexican-American servicemen were not segregated from the majority.

“On June 15, 1945, while scouting for enemy positions in a jungle of the Philippines, Felix was struck by a Japanese sniper’s bullet and killed instantly. Back in Three Rivers, his widow Beatrice and their little girl waited three years for word that his remains were being transported home for a proper burial. She arranged to have his wake held at the local mortuary rather than in her own living room, as was the Mexican custom.

“Just before the train arrived, the owner of Rice Funeral Home told Beatrice that she would have to change her plans. The establishment couldn’t provide its chapel service for the Longorias after all, he said, ‘because the Whites would not like it.’

“The broken promise doubled Beatrice’s grief. She could scarcely believe that fellow Americans, whom Felix had died to protect, still viewed him as a second-class citizen. Quickly, her pain gave rise to anger, and then to action. Beatrice and her family resolved that the world outside Three Rivers should hear their story.

“Through a veterans’ organization in Corpus Christi, the news reached Washington. During a protest meeting at Three Rivers, a courier delivered a message from U.S. Senator Lyndon Johnson of Texas: ‘I have today made arrangements to have Felix Longoria reburied with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery … where the honored dead of our nation’s wars rest.’

“The funeral took place on February 16, 1949, as a gray drizzle shrouded the gentle slopes of Arlington. Felix’s whole family was there. Senator Johnson and his wife came to pay their respects. Mexican diplomats brought flowers in tribute from their country.

“A state legislative investigation initially concluded that no racial discrimination had occurred against Beatrice Longoria, but members later called the report into question and it was withdrawn. Felix’s burial at Arlington reversed one glaring injustice, but, even for his family, it didn’t provide all the answers. Years later, his sister-in-law still asked herself, ‘Why should I have to come so many miles away to this cemetery? How many Felix Longoria cases must have gone unheard of?”‘

I don’t know how many cases like this went unheard. If there was even one more, and I’m sure there was, it was one too many. The living heroes of this story must include Beatrice Longoria and then-Senator Lyndon Johnson. She had the courage to challenge bigotry and he had the compassion and strength to right a wrong.

Widow of Pvt. Felix Z. Longoria dies

Burial dispute drew attention to GI Forum

By Israel Saenz (Contact)

28 March 2008

Beatrice Longoria wanted her husband buried with family.

Beatrice Longoria was a shy woman who didn’t look for a fight, but in 1949 the fight found her and her family, and in the process catapulted the Mexican-American civil rights movement to national prominence.

Her death early Thursday at age 88 fell during a week celebrating that movement.

A Three Rivers funeral home in 1949 had refused to host services for her husband, Private Felix Z. Longoria, after his death in the Battle of Luzon during World War II. She and her family’s next steps drew national attention to South Texas and a new area veteran advocacy group called the American GI Forum.

Beatrice Longoria’s death comes only a day after organization members celebrated its 60th anniversary and while members convened in Corpus Christi for the group’s mid-year conference. Members were shocked Thursday as news of her death spread.

“We are saddened by the loss,” said Antonio Morales, American GI Forum national commander. “Felix Longoria served his country twice — once as a soldier defending the principles our country was founded on and in giving life to the Hispanic community.

“We join the family in their prayers.”

Beatrice Longoria lived in Westminster, Colo., for the past seven years, her granddaughter Veronica Sizemore said.

In 1949, after the funeral home refused to host Felix Longoria’s services, Longoria went to her family members. Her sister Sara Posas, who lives in Portland, said Thursday that Longoria wanted her husband to be buried with his family members in Three Rivers.

“She was confused about defending her rights,” Posas said. “I asked her, ‘Would you like for me to call someone who can help you?’ Of course, she said yes.”

Posas said by the next day, local physician Hector P. Garcia, who only the previous year had helped found the forum, had drawn the national spotlight to the incident.

“We were even getting calls from overseas,” Posas said.

Senator Lyndon B. Johnson worked to secure burial for Longoria at Arlington National Cemetery — creating a lifelong bond and political partnership between Johnson and Garcia, as well as drawing attention to the American GI Forum.

“It propelled us into a national organization, where individuals wanted to know more about starting chapters in their states,” Morales said, adding the organization has plans to mark the 60th anniversary of Longoria’s burial next year.

Services for Beatrice Longoria will be held in Colorado, but Posas said family members likely will hold area services as well.

Survivors also include three children, Adela Longoria Cerra, Jose Garcia and Christine Estorga; three sisters, Luisa Martinez, Jerry Davila and Marge Harris; a brother, Juventino Moreno; 10 grandchildren; and 15 great-grandchildren.

After Felix Longoria’s burial, the forum and Garcia took off into civil rights history and a slew of social battles. Longoria went quietly back into private life a single mother, without the controversy or fights. Relatives say, however, that she was well-aware of what the incident accomplished.

“She was a very strong woman, even after the prejudice that was shown to her,” Sizemore said. “She was very proud of that legacy.”

LONGORIA, FELIX Z

- PVT USAGF- 27TH INF

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 02/16/1949

- BURIED AT: SECTION 34

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard