NEWS RELEASE from the United States Department of Defense

No. 468-04

IMMEDIATE RELEASE

The Department of Defense announced today the death of a soldier who was supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Second Lieutenant Leonard M. Cowherd, 22, of Culpeper, Virginia, died May 16, 2004, in Karbala, Iraq, when he received sniper and rocket propelled grenade fire while securing a building near the Mukhayam Mosque. Cowherd was assigned to Company C, 1st Battalion, 37th Armor Regiment, 1st Armored Division, Friedberg, Germany.

The incident is under investigation.

“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers. For he today who sheds his blood with me shall be my brother. Be he ne’er so vile, this day shall gentle his condition, and gentlemen in England now abed shall think themselves acursed they were not here, and hold their manhoods cheap whilst any speaks, that fought with us upon St. Crispin’s day!”

– Henry V

Photos Courtesy of the United States Military Academy

Culpeper service is set for soldier killed in Iraq

Saturday service planned for Culpeper Lieutenant killed in Iraq

21 May 2004

A memorial service for an Army officer killed in Iraq will be held Saturday at 2 p.m. at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Culpeper.

Second Lieutenant Leonard Cowherd III., 22, was killed by a sniper Sunday while on a mission near Karbala.

“We’re not sure whether it will be a memorial service or a funeral,” a spokesperson for St. Stephen’s said yesterday. “The body is still en route.”

Cowherd, Culpeper’s first war casualty since Vietnam, was a member of St. Stephen’s Episcopal. He attended Wakefield Country Day School in Rappahannock County and was a 2003 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy.

He was a platoon commander in the tank corps and had been in Iraq since January. He reportedly was scheduled to leave in April, but his tour of duty was extended when the fighting escalated.

His parents, Leonard and Mary Ann Cowherd, live near Mountain Run Lake in Culpeper County. His twin brother, Charles, is a 2003 Virginia Military Institute graduate now attending graduate school in Boston.

The St. Stephen’s spokesperson said the family has requested that only one member of the news media be allowed at the service. Burial will be in Arlington National Cemetery at an as-yet undetermined date, the spokesperson said.

Town streets lined with flags in honor of fallen soldier

C. Clark Ballew

Courtesy of the Culpeper Star Exponent

Thursday, May 20, 2004

Flags honoring Second Lieutenant Leonard Cowherd line Main Street Wednesday. When the sun peeked out from behind the clouds covering Culpeper Wednesday, streaky reflections of red, white and blue tinted the storefront windows lining Leonard Cowherd’s hometown.

Main and Davis streets were decorated overnight with 50 American flags, each a symbolic reminder of the 22-year-old Army Second Lieutenant killed Sunday in Iraq.

Culpeper Town Council members unanimously voted to erect the flags in Cowherd’s honor during their committee meeting Tuesday.

“I think it’s rather obvious that it was a great idea,” said Mayor Pranas Rimeikis, who sent the Cowherd family a condolence letter Wednesday.

“I’ve known Lenny since he was a teenager,” the mayor said. “We’re all pretty shook up by it. It really puts a face on this war for all of us.”

Cowherd, a platoon commander in Iraq since January, was the county’s first wartime casualty since Vietnam.

A spokeswoman for the United States Military Academy said Cowherd was the eleventh graduate killed in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Cowherd graduated from West Point in 2003.

Since his death, Culpeper has been awash in glowing sentiment for its latest fallen son.

“He represented the best that Culpeper had to offer,” said John Coates, chairman of the Culpeper County Board of Supervisors, “a person very dedicated to his principals and what he believed in.”

Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld, the scheduled commencement speaker at the May 29 U.S. Military Academy graduation, is believed to have plans of working Cowherd into his speech, a family friend said Wednesday.

Cowherd was a 2003 graduate of West Point.

Also, a representative with the CBS news magazine program “60 Minutes” contacted the Star-Exponent Wednesday with intentions of using Cowherd’s story.

Though the exact format is still undetermined, the program is planning a tribute to fallen soldiers on its May 30 broadcast at 7 p.m.

Culpeper Officer Killed in Iraq

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Tuesday, May 18, 2004

Army Second Lieutenant Leonard M. Cowherd, 22, of Culpeper, Virginia, heir to a amily tradition of patriotism that went back to the American Revolution and Valley Forge, graduated from West Point and was sent to Iraq.

In an e-mail sent in March to the editor of his hometown newspaper, he said he looked forward “to coming home to Culpeper soon.” But, people who knew him said, his stay in Iraq was extended.

Two days ago in Karbala, Cowherd was killed when he was hit by sniper and rocket-propelled grenade fire while securing a building near the Mukhayam Mosque. The Pentagon made the announcement yesterday.

“He was a fine young man,” Henry Pusey of Winchester, who knows the Cowherd family, said last night. Said Scott Cooper, who had taught Cowherd at Wakefield Country Day School in Flint Hill, Virginia: “He was a young man committed to his patriotic duty.”

Cooper, a retired Coast Guard Captain who taught computer applications to Cowherd, called him “a top-notch student, a superior student,” whose intelligence extended beyond the classroom.

He was “very much aware of things going on, very much engaged in things going on around him, very quick to perceive issues,” Cooper said. “A very bright young man.”

In the Army, Cowherd was assigned to Company C, 1st Battalion, of the 37th Armor Regiment of the 1st Armored Division, based in Germany.

On three successive weeks in March, Cowherd published guest columns in the Culpeper Star-Exponent newspaper, depicting “a soldier’s firsthand experiences in Iraq,” said managing editor Rob Humphreys.

In a telephone interview last night, Humphreys described the columns as “very good stuff.” Cowherd, who Humphreys said was a student of history, “wrote about his experiences with the Iraqi people, Iraqi children . . . basically with military life over there.”

In the columns, Cowherd told how he felt about those whom he was leading, Humphreys said.

“I’m extremely proud of the soldiers in my platoon,” Cowherd wrote. “They have endured countless hardships here in Iraq as well as the overall hardship of being away from one’s home and family.”

Humphreys said that Cowherd’s death marked Culpeper’s first war fatality since Vietnam. Cowherd was the 12th West Point graduate killed in Iraq.

He was the son of Leonard and Mary Ann Cowherd, Humphreys said. A Virginia resident who was a member of the Sons of the American Revolution with Cowherd’s father recalled how the elder Cowherd told a meeting of the group about his son’s graduation from West Point.

“He was kind of proud,” said Richard Schnorf of Delaplane. “As you can imagine.”

Leonard Cowherd writes home

A collection of columns from fallen soldier Leonard Cowherd

Sourtesy of the Culpeper Star Exponent

Friday, May 21, 2004

March 13

A Culpeper soldier on military life in Baghdad

Hello, Culpeper! This is Leonard Cowherd reporting from Northern Baghdad. I arrived here in late January and took over my first platoon a little over a month ago. Most of the members of my platoon have been here since late April or early May of last year.

They have endured an incredible amount of hardships, in terms of living conditions, weather and difficult missions. I feel privileged and honored to be the platoon leader of these fine men. We are all patiently awaiting our return to our home station in Germany, which should be in the next couple of months.

My unit is currently living in what used to be a small amusement park known as Baghdad Island. Saddam Hussein diverted the Tigris River to create this small resort for him and his elite group of followers. We have taken it over as our FOB, or Forward Operating Base. Most just call it “the Island.” Some soldiers live in what used to be a bowling alley, others within site of a rickety roller coaster and ferris wheel.

The guard towers on the west side afford a magnificent view of the Tigris River and Northern Baghdad. Since I’ve been here, the temperature has ranged between the low 50s to the high 80s, although I am told that within a few days, the weather can jump to highs of above 100.

The conditions over here in terms of amenities are remarkable, nothing like the hardships that veterans of previous wars had to endure. When the unit first arrived here, there was pretty much nothing, but now sometimes you forget that you are in a combat zone.

Private contractors control most of the Island’s support services. We have a dining facility complete with salad bar, desert bar, short-order and homestyle food that serves four meals a day (the fourth meal is from 2330-0100 – great before or after a night mission).

The laundry service is free and reliable and can turn a bag full of filthy clothes back around to you in about 48 hours. I’m currently working at one of the three (yes, three) Internet Cafes on the Island. This one is free, but for about $2 an hour you can get a connection with a faster speed than the other two. There is an international phone center that is a little pricy at 40 cents a minute, but better than nothing. For other items, local Iraqis have been brought on post and have set up shops, selling us a wide variety of stuff – from hygiene products to DVD player sand DVDs.

Any time you go off the island, the danger is real, although not always apparent. For the most part, the Iraqi citizens accept our presence. The children especially chase down our vehicles, cheer loudly and give a “thumbs up” whenever we drive by. Vendors of bananas, cigarretes and soda line the streets, highways, even major bridges, and attempt to see us their waves.

Most Iraqis appear to live either in poverty or … how can I say it … even worse poverty. This is a situation that we are trying to help. The roles that the American soldier must play are numerous: diplomat, traffic cop, judge, humanitarian assistant, and warfighter. The soldiers over here have done an incredible jog juggling those different roles. Yet there is still much to be done.

March 20

Most Iraqis want to be friends with U.S. troops

It is amazing how much Baghdad can change in just a few miles. One minute you are driving along a major highway, with hundrdes of cars, street lights, massive overpasses, entrance ramps and exit ramps. You turn down a side street and then onto a dirt road, and a farmer passes in front of your convoy, trailed by a herd of sheep, oblivious to the presence of the three armored humvees in his midst.

Despite their poverty, however, generosity and hospitality are strong characteristics of the Iraqi people. During a recent mission, a farmer brought out a pot of tea for myself and the soldiers in my vehicle, complete with saucers, tea cups, teaspoons and sugar.

I’ll never forget my first patrol. Riding as the guest of a fellow platoon leader, my eyes were wide open as we exited the gate to the island. I wanted to take in as much informtion as possible before I took over my platoon.

On that first patrol, we traveled to a village on the bank of the Tigris River that has even narrower streets than is normal for Baghdad. As we bumped our way down the road, children began crowding around our vehicles, giving us the thumbs up sign and asking for “shakolata.”

We exited our humvees to talk to the local village leader about ongoing security, electrical and sanitation issues. “Hello, mister,” an Iraqi greets me, and children began to point and tug at items on my uniform. A soldier breaks out a digital camera, and kids push and prod to get in his picture.

Not used to this consternation, I make my way through the crowd toward the village leader with my hand resting on my holstered pistol. Another man comes right to me, puts his hand gently on my arm and says, “There is no need for that. We are all friends here.”

At the same village a few weeks later, a young Iraqi approaches one of of my soldiers and asks angrily when the Americans are going to leave Iraq. With utmost professionalism, the soldier responds that we don’t want to stay in Iraq any longer than we have to, and that we are trying our best to help the Iraqi people, despite the everyday dangers that we face.

For the most part, the first instance is a more accurate description of the relationship beteen Iraqis and Americans. They are glad to be out from under the yoke of an oppressive tyrant, but are still lacking basic services that people in the States take for granted.

My main goal here is to do as much as we can to help, but at the same time ensuring that everyone gets home safely.

March 27

Typical day is different each day of the week

It would be difficult to describe the “typical” day here, as they are almost all different. Looking over an old “to-do list” in my notebook from a few weeks ago, I marveled at all the different sorts of things that are going on at the same time here.

The page read: “1. Pick up laundry, 2. Link up with dog handlers before tonight’s mission, 3. Clean pistol, 4. Talk to platoon sergeant about condition of schools in sector, 5. Help soldier with resume, 6. Check serial numbers on radios.”

And the next day the list was completely different. In general, support for Coalition forces is building, and resistance elements are becoming more difficult to find. Unfortunately, part of our job involves inconveniencing the majority (through vehicle and personal searches) in order to find the small minority. I think most Iraqis understand the necessity of our presence, but look forward to the day when they themselves are responsible for their security.

I wish that I had taken Arabic in college. I have learned how to say the basics: “Hello,” “Goodbye,” “thank you,” “Peace Be With You,” “Stop,” “Go,” as well as things like “Open all the doors, the hood, the trunk, the glove box, turn off the engine, and stand over here, please.”

The art of conversation, however, is far beyond my ability. We rely on a group of interpreters – Iraqis who live nearby – to converse with people on a daily basis. One of my biggest jobs is to communicate with other people, and without an interpreter, that would be nearly impossible. Talking with interpreters is one of the best ways to learn about the culture of Iraq. Each has a unique story to tell about his life – and in each of those stories is the story of a country plagued by war and despotism for over 30 years.

I am extremely proud of the soldiers in my platoon. They have endured countless hardships here in Iraq, as well as the overall hardship of being away from one’s home and family. It has been a year since they left Germany. I think of all the things that I have done in the past year since they got here – all the things that they did not have an opportunity to do. They have essentially put their lives on hold while they have been over here.

When I first arrived, I really did not know what was going on. Everything was new, the people, the terrain, my job. On my first mission, one of my soldiers said, “Sir, we’ll take care of all the details, just jump on the humvee before we leave and you’ll be OK.”

I only wish that my actual job was that easy, but the overall intent behind his statement was that they would do everything they could to make my job easier. I am proud of the job that they have done, and proud to be over here with them.

This will unfortunately be my final submission. As our stay here comes to a close, it is becoming increasingly difficult to gain access to the Internet and find the time to write. I look forward to coming home to Culpeper soon.

Thank you all for your support

23 May 2004:

A soldier killed in Iraq was remembered Saturday as a positive thinker whose outlook would have been helped those he left behind cope with his loss.

An estimated 400 people packed St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church here to remember Second Lieutenant Leonard M. Cowherd III, a 22-year-old West Point graduate and newlywed who was cut down by a sniper as he stood outside his tank a week earlier in Karbala, Iraq.

“He was my everything, and he was ever since the day I met him,” Cowherd’s widow Sarah said, sobbing. “My heart, my soul, my friend and my husband.”

The couple married June 28, 2008, shortly after his graduation from the U.S. Military Academy. In January, he shipped out to command four tanks and 16 men in Iraq.

“He could make any negative situation into a positive situation, and I really wish he was here to help us through that right now,” Sarah Cowherd said.

Speakers also included Cowherd’s twin, Charles, who joked about how much the brothers hated twin jokes, and retired General Barry McCaffrey, who taught Cowherd at West Point and read from a letter he wrote to Cowherd’s parents in December 2002.

“His dedication and professionalism impresses me tremendously,” McCaffrey wrote to Mary Ann and Leonard Cowherd II. “He is an outstanding young soldier.”

“His life, in my judgment, was a tremendous, shining example,” McCaffrey said.

With a crowd at well over the church’s capacity of 220, the remainder of the mourners watched on closed-circuit TV in the fellowship hall and under outdoor tents.

Cowherd became Culpeper County’s first war-time fatality since the Vietnam War.

He will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery on Wednesday.

Iraq’s shadow extends to West Point

Michael Winerip, New York Times

February 13, 2005

WEST POINT, N.Y. — For most Americans, Iraq is very far away. But for the cadets at the U.S. Military Academy, particularly the seniors who will soon be officers over there, the war intrudes daily.

West Point has added classes on how to avoid ambushes, proper convoying techniques, the correct procedure for emptying a room when fighting door to door. “I’m 22 years old,” said Cadet Ramon Ramos, “and sometimes I’ll think, ‘Wait a minute, did I really just have a class on how not to get blown up by an insurgent?’ “

E-mail brings the war to the dorms. The night before the battle for Fallujah began, senior Mark Erwin got a message from his brother, Lt. Mike Erwin, West Point ’02: “Markie — I will be carrying your cadet picture in my right breast pocket with my prayer to St. Michael, dog tags and St. Michael’s medal,” the big brother wrote. “If by some chance something happens to me, you’re the voice to the family.”

Cadet Erwin never deletes an e-mail message from his brother. “You worry there might not be another,” he said.

Lunch can be the worst.

“If they say the words, ‘Please give your attention to the first captain,’ you know it’s coming,” said Cadet Michael Linnington.

Another senior, Cadet Megan Williams, said: “Everyone shuts up. You’re so afraid of it.”

Linnington explained: “There was one the other day. The first captain gives a 30-second spiel — what year they graduated, how they died, if they were married.”

The death of Todd Bryant (’02) in Fallujah touched many seniors. When Ramos was an 18-year-old plebe, Todd Bryant was his intramural football coach. “I sat at his table,” Ramos said. “Some upper class give plebes a hard time. Not Todd. He was just a nice guy.” Company D named a meeting room for Todd Bryant last month. “His family and wife came from California,” Linnington said. “They had a slide show about his cadet life, and you watch it — it’s your life. What we’re doing now, it’s what he did. It puts it into reality.”

Barely aware

The cadets feel strange being so preoccupied, when their friends outside the military seem barely aware. Williams has a younger sister going to college at home in Texas. “You try not to judge,” Williams said, “but they’re very oblivious.”

Cadets go to more funerals than most 20-year-olds. Williams attended a service for David Bernstein (’01), killed in an ambush in Taza. “I didn’t know him,” she said. “But I’m Jewish, and he was, and that touched me.”

When Cadet Brandon Bodor was in Washington for the inauguration, he stopped at Arlington National Cemetery, at the grave of Leonard Cowherd (’03), who was killed in Karbala. “Lenny was a good guy,” Bodor said.

Cadets don’t have to study the opinion polls to know they’re heading off to an unpopular war. Applications to the military academies are down substantially. At West Point, applications hit a post-9/11 high of 12,383 for the school year that began 2003. The 10,412 applications for the coming school year represent a 16 percent drop in two years.

The Naval Academy is down 2,852 applicants, a 20 percent drop in just a year, and the Air Force Academy is down 3,054 applicants from 2004, a 24 percent drop.

After two years at West Point, a cadet is given a last chance to leave without having to serve in the military. Last summer, 52 members of the sophomore class of 963 left, compared with 32 the year before and 18 the year before that. West Point officials were relieved it wasn’t more. “We were hearing rumors of mass resignations,” said the admissions director, Col. Mike Jones. “But it was just rumors. Our numbers are down, but still very strong,” he said, citing 10 applicants for every slot.

Bodor said it’s no mystery why the numbers are down. “Iraq,” he said. “Same as Vietnam. When you’re in an unpopular war, people question, ‘Is this what I want to be doing?’ “

These cadets, who get a free education in return for five years of military service, are likely to face two Iraq tours if current projections hold. Their own feelings about the war seem surprisingly mixed. While Erwin and Williams expressed confidence in the effort to establish a democratic society in Iraq, Linnington, Ramos and Jarick Evans sounded less hopeful.

“There are cadets who might not want to go, they might not believe we should be over there the same way the American public feels,” Linnington said. “But as military people we have a duty.”

Ramos sees the division of opinion in classroom discussions. “At this point, to me, it’s too late to debate,” he said. “We may not like it, but we have to make the best of it. We’re there.”

He is grateful, he said, “that the American public knows it’s not the soldiers’ fault if they disagree with the war.”

Remembering a life cut short by a bullet

Rob Humphreys

Culpeper Star Exponent

Sunday, May 15, 2005

A year ago tomorrow, all hell broke loose. First in Iraq. Then in Culpeper.

Leonard M. Cowherd, a 22-year-old second lieutenant fresh out of West Point, had just emerged from his tank when a sniper’s bullet and rocket-propelled grenade tore into his body at a mosque in Karbala.

Cowherd, who led a platoon of four tanks and 16 men, became the first – and hopefully last – soldier from Culpeper to die in Iraq.

When word reached the Star-Exponent the following morning, we dropped everything to focus on our departed friend and editorial correspondent.

As luck would have it, only former reporter C. Clark Ballew and myself were in the newsroom that day, but we managed to overcome the frenzied task of tracking down a story that nobody in his right mind wants to report.

Writing about Cowherd’s death posed the most somber assignment in my 12 years of journalism.

Listening to his Army friends and new bride eulogize his memory during a packed memorial at St. Stephens Episcopal brought tears to my eyes.

Watching his parents try to stay strong during an interview with HBO months later – well, I just lost it. So did everyone else.

In the year since Cowherd’s death, Culpeper has come full circle with the war in Iraq. We have seen first hand the carnage of battle, we have grieved and we have healed.

And now, as we send a fresh batch of soldiers into the chaos that is the Middle East, we can only pray that the men and women in the Army’s 3rd Battalion of the 317th Regiment do not meet the same fate.

A solemn tribute

On April 23, the day that Culpeper held a send-off rally for its troops, my father and I visited Arlington National Cemetery, site of Cowherd’s grave.

Walking from the Confederate section of the cemetery high atop the bluffs that overlook the Potomac, we descended the steep roads that snake through our nation’s most hallowed ground, quietly reflecting on the sacrifice of generations past.

World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam – the brave men who dutifully spilled their blood on foreign soil to spread democracy, liberate entire populations and uphold God-given truths.

Second Lieuteant Leonard Cowherd died for the same ideals in our nation’s war on terror. So did the hundreds of soldiers whose freshly marked graves in Section 60 bear the heartache of those who are left to weep – heart-wrenching pictures of family, letters from young children and small rocks atop the neatly arranged, government-issued, white slab headstones.

I never had the opportunity to meet Leonard – we only corresponded through e-mail – but as a fellow Civil War buff, I was looking forward to his return. “Drop by when you get back to Culpeper,” was my last e-mail to him. “I’d be honored to meet you – and talk Civil War.”

Obviously, that chance never came. But on a cold, windy day in late April, I took solace in paying tribute to a courageous man who selflessly gave his life to serve our country.

Thank you, Leonard.

You made Culpeper proud.

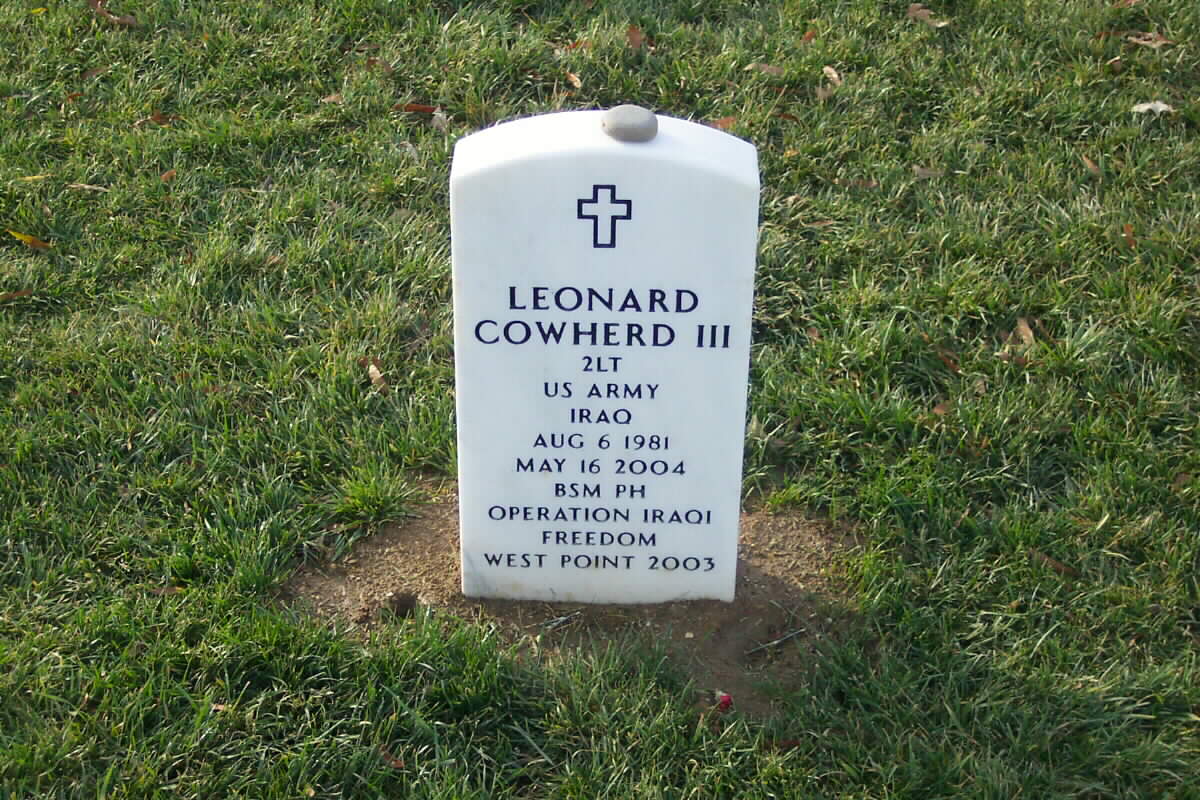

COWHERD, LEONARD III

2LT US ARMY

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 05/31/2003 – 05/15/2004

- DATE OF BIRTH: 08/06/1981

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/16/2004

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 05/26/2004

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 7983

Arlington National Cemetery

COWHERD, LEONARD III

2LT US ARMY

IRAQ

- DATE OF BIRTH: 08/06/1981

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/16/2004

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 7983

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard