Lloyd L. “Scooter” Burke, 74, a retired Army Colonel who was awarded the Medal of Honor for bravery in the Korean War and later retired as a congressional liaison, died of a heart attack June 1,1999 at his home in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Colonel Burke, who served in three wars over 35 years, lived in the Washington area off and on from 1963 to 1988, when he moved from Burke, Virginia, to Alabama.

He won the Medal of Honor for an assault on three North Korean bunkers near the Imjin River in October 1951. Then a First Lieutenant, he led his 35-man company under intense fire, killing more than 100 North Koreans himself and suffering wounds in return, according to the Medal of Honor citation.

Colonel Burke then made lone charges on two of the bunkers and killed the crews, the citation said. He threw grenades at the third bunker and then tossed back Several of the grenades that were hurled at him. His men then overran the position but were pinned down by fire. Colonel Burke set up a gun, wiped out 75 North Koreans and destroyed two mortar emplacements. He led his men forward and killed 25 of the retreating soldiers. None of his men were killed.

Colonel Burke’s wartime exploits were featured in an episode of the A&E television series “Heroes” a decade ago.

His other military decorations included the Distinguished Service Medal, Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, four Army Commendation Medals, the Joint Service Commendation Medal, five Purple Hearts and three Bronze Stars.

Colonel Burke was born in Tichnor, Arkansas. He was a graduate of Henderson State University. He served in Italy during World War II and in Vietnam as an infantry battalion commander during the Vietnam War. He was severely wounded during that war.

Colonel Burke also served in Germany and retired in 1978 as Chief Army liaison to the House of Representatives.

After he retired, he was lobbyist for the American Trial Lawyers Association and Sperry Rand Corp.

Later he worked to establish the Korean War Veterans Memorial and participated in the dedication on the Mall.

He was national president of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, a director of Messiah United Methodist Church in Springfield and a member of the Retired Officers Association, First Division Association, Democratic Club, Army Navy Club and Army Navy Country Club.

His marriage to Virginia Fletcher Burke ended in divorce. His second wife, Maxine Hardin Burke, died in the early 1990s.

Survivors include three children from his first marriage, John Gary Burke, Leslie Ann Burke and Lloyd Douglas Burke, all of Springfield; three sisters; and five grandchildren.

BURKE, LLOY.D L., COL, USA (Ret.) ”Scooter”

On June 1, 1999, in Hot Springs, Arkansas, beloved father of Gary Burke, Leslie Ann Burke and Lloyd D. Burke, all of Springfield, Virginia; brother of Donna and Howard Eddins and Dorothy Burke, all of Hot Springs, Arkansas, and Betty and Lloyd Lorince of Stuttgart, Arkansas, and the late Claude D. Burke. He was preceded in death by his second wife, Maxine Hardin Burke. Also survived by five grandchildren, numerous nieces and nephews and the mother of his children, Virginia Fletcher Burke of Springfield, Virginia. Funeral will be held at Fort Myer Chapel at 11 a.m., Friday, June 11, 1999, followed by interment in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions may be made to The Arkansas Medal of Honor Memorial, PO Box 784, North Little Rock, Arkansas 72115. For further information, call Nick Bacon at 501-370-3820.

By John Lang / Scripps Howard News Service, July 1999

When this old warrior went down at last, heroes mourned.

It was a lovely day in June when they put the box of ashes that was Lloyd Burke into the sunlit grave below the hill crowned by the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery.

One by one each laid a white rose alongside the little box, six aging men, five with blue ribbons around their necks, one with a blue rosette in his lapel — the decorations of the bravest of the brave, Congressional Medals of Honor.

Burke was one of them, a legend even to them, and yet strangely, to the people of the land he served, he was nobody.

Who, this day, outside of his family and this band of brothers, knew the name, Lloyd Burke? What he did was never on television, not much in newspapers after passing mentions. Television couldn’t have been there. If it had, it couldn’t have shown the things he did.

Burke caught hand grenades in midair and threw them back. It’s in the citations. He killed people. He was just about the best at that, when he had to be. In one day in the Korean War, he, single-handedly to save his men, slew a hundred foe. He was as honored for this and for other actions as were Alvin York in World War I and Audie Murphy in World War II. He was that rarest of soldiers, rising from private to sergeant in WW II, a lieutenant in Korea, a colonel in Vietnam, earning the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, the Distinguished Service Medal, the Silver Star, the Bronze Star with two clusters, five Purple Hearts, four Army Commendations, the Korean Medal of Honor, the Vietnam Cross.

A three-war hero. A nobody.

How many, after all, were aware? The irony of Burke’s burial in times like these was palpable. The day they put his remains in the hallowed ground, America appeared to be finishing a war, a war with this casualty count: enemies 5,000, our boys 0. There was not a man on our side such as Burke in Kosovo. It was not his kind of war.

America didn’t want the risks it takes to make a hero f his sort. The polls showed that. The people wanted a war without losses. The president, Congress and the Pentagon made it plain the original element of warfare — the foot soldier — was a weapon of last resort.

“No more Vietnams” is the watchword of today’s leaders. This could mean, if they can avoid the messy conflicts, no more legends like the man who came out of Tichnor, Arkansas, population then 75, nicknamed “Scooter,” and slogged his way up the ranks to head of congressional liaison for the Army on the merit of uncommon character.

There were men with empty sleeves at Burke’s funeral, men who limped. There were old men with old wounds who eased into the pews of Old Chapel at Fort Myers on the edge of Arlington. They wore little bars in their civilian suit lapels, denoting this and that award for valor. Some wiped at wet eyes as some of his family sobbed.

All chuckled, once, when his daughter Leslie, who gave his eulogy in a breaking voice, told how he was a wonderful father — not only to her but to every child he came across — always organizing games for neighborhood children and always making up the rules as he went along so he could be the quarterback no matter which side had the ball, and she ended up confessing, “He never wore a seat belt.”

A company of the tall soldiers of the Old Guard led the procession to the grave, behind a horse-drawn caisson and a riderless horse with boots reversed in the stirrups, symbol of the fallen hero. There were active-duty officers of high rank, for if generals wanted no more wars of the kind Burke fought, they surely wanted how he fought remembered.

The passage in the funeral program taken from Burke’s Medal of Honor citation read like an account of deeds of battle of yore — anachronistic now.

It was October 28, 1951, Chong-dong, Korea, and Burke’s platoon, under attack, outnumbered, exhausted, was out of fight. Except Burke:

“Dashing to an exposed vantage point he threw several grenades at the bunkers, then, returning for an M1 rifle, he made a lone assault, wiping out the position and killing the crew. Closing on the center bunker he lobbed grenades through the opening and, with his pistol, killed three of its occupants attempting to surround him. Ordering his men forward he charged the third emplacement, catching several grenades in midair and hurling them back at the enemy.

“… Securing a light machine gun and three boxes of ammunition, 1st Lt. Burke dashed through the impact area to an open knoll, set up his gun and poured a crippling fire into the ranks of the enemy, killing approximately 75. Although wounded, he ordered more ammunition, reloading and destroying two mortar emplacements and a machine gun position with his accurate fire. Cradling the weapons in his arms, he then led his men forward, killing some 25 more of the retreating enemy and securing the objective.”

One there to bury Burke, another with a Medal of Honor, another retired Colonel, was a Marine, Barney Barnum, who wanted it understood that he and Burke had not, actually, won their medals.

“Recipient,” he said, “not winner. You go out to win ball games. You don’t go out to win awards. That’s a big distinction. People who got awards for actions they did, they did not do it for the national command authority, for apple pie and the flag. You did it because you didn’t want to let down the guy on the right and the guy on the left. To protect a buddy, you did things.”

The last time Barnum saw Burke alive was just weeks before, at the dedication of the Medal of Honor Memorial in Indianapolis on Memorial Day. There were 97 recipients of the nation’s highest award at the ceremony. Barnum was with them there for the same reasons he and some of his peers were back together so soon again paying respects to Burke, dead now at 74.

“I think our presence is to say, Hey, you are enjoying the future because of the past.”

So there he was, among the graying mourners, when another with two stars on each shoulder walked up to a man wearing the blue rosette, saluted him first, as even the highest officers do for such a one, smiled wistfully, and said, “Scooter Burke, a great American.”

But who, beyond the heroes, knew?

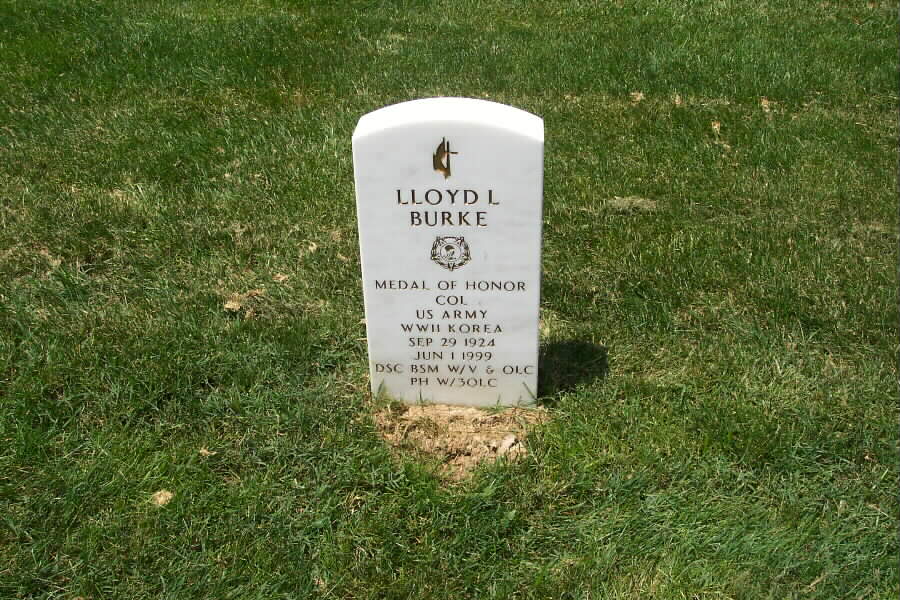

Burke, Lloyd L.

Born. 20 September 1924, died 1 June 1999.

US Army, Colonel

Res: Springfield, Virginia,

Section 7A, Grave 155, buried 11 June 1999

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard