Shuttle Columbia Memorial Dedicated: 3 February 2004

LAUREL BLAIR SALTON CLARK, M.D. (CAPTAIN, USN)

NASA ASTRONAUT

PERSONAL DATA: Born in Iowa, but considers Racine, Wisconsin, to be her hometown. Died on February 1, 2003 over the southern United States when Space Shuttle Columbia and her crew perished during entry, 16 minutes prior to scheduled landing. She is survived by her husband and their child. Laurel enjoyed scuba diving, hiking, camping, biking, parachuting, flying, traveling. Her parents reside in New Mexico.

EDUCATION: Graduated from William Horlick High School, Racine Wisconsin in 1979; received bachelor of science degree in zoology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1983 and doctorate in medicine from the same school in 1987.

ORGANIZATIONS: Aerospace Medical Association, Society of U.S. Naval Flight Surgeons.

AWARDS: Navy Commendation Medals (3); National Defense Medal, and Overseas Service Ribbon.

EXPERIENCE: During medical school she did active duty training with the Diving Medicine Department at the Naval Experimental Diving Unit in March 1987. After completing medical school, Dr. Clark underwent postgraduate Medical education in Pediatrics from 1987-1988 at Naval Hospital Bethesda, Maryland.

The following year she completed Navy undersea medical officer training at the Naval Undersea Medical Institute in Groton Connecticut and diving medical officer training at the Naval Diving and Salvage Training Center in Panama City, Florida, and was designated a Radiation Health Officer and Undersea Medical Officer. She was then assigned as the Submarine Squadron Fourteen Medical Department Head in Holy Loch Scotland. During that assignment she dove with US Navy divers and Naval Special Warfare Unit Two Seals and performed numerous medical evacuations from US submarines.

After two years of operational experience she was designated as a Naval Submarine Medical Officer and Diving Medical Officer. She underwent 6 months of aeromedical training at the Naval Aerospace Medical Institute in Pensacola, Florida and was designated as a Naval Flight Surgeon.

She was stationed at MCAS Yuma, Arizona and assigned as Flight Surgeon for a Marine Corps AV-8B Night Attack Harrier Squadron (VMA 211). She made numerous deployments, including one overseas to the Western Pacific, practiced medicine in austere environments, and flew on multiple aircraft. Her squadron won the Marine Attack Squadron of the year for its successful deployment.

She was then assigned as the Group Flight Surgeon for the Marine Aircraft Group (MAG 13). Prior to her selection as an astronaut candidate she served as a Flight Surgeon for the Naval Flight Officer advanced training squadron (VT-86) in Pensacola, Florida.

Captain Clark is Board Certified by the National Board of Medical Examiners and holds a Wisconsin Medical License.

Her military qualifications include Radiation Health Officer, Undersea Medical Officer, Diving Medical Officer, Submarine Medical Officer, and Naval Flight Surgeon. She is a Basic Life Support Instructor, Advanced Cardiac Life Support Provider, Advanced Trauma Life Support Provider, and Hyperbaric Chamber Advisor.

NASA EXPERIENCE: Selected by NASA in April 1996, Dr. Clark reported to the Johnson Space Center in August 1996. After completing two years of training and evaluation, she was qualified for flight assignment as a mission specialist. From July 1997 to August 2000 Dr. Clark worked in the Astronaut Office Payloads/Habitability Branch. Dr. Clark flew aboard STS-107 and logged 15 days, 22 hours, and 20 minutes in space.

SPACE FLIGHT EXPERIENCE: STS-107 Columbia (January 16 to February 1, 2003). The 16-day flight was a dedicated science and research mission. Working 24 hours a day, in two alternating shifts, the crew successfully conducted approximately 80 experiments. The STS-107 mission ended abruptly on February 1, 2003 when Space Shuttle Columbia and her crew perished during entry, 16 minutes before scheduled landing.

Captain Clark will be laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery (Section 46, Grave 1180-2) on 10 March 2003. She will be buried next to fellow Astronaut Michael P. Anderson.

Laurel Clark, 41, a commander (captain-select) in the U.S. Navy and a naval flight surgeon, was Mission Specialist 4 on STS-107.

Clark received a bachelor of science in zoology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1983 and a doctorate in medicine from the same school in 1987.

Clark, as a member of the Red Team, worked with the following experiments: European Space Agency (ESA) Advanced Respiratory Monitoring System (ARMS); Astroculture (AST-1 and 2); Biotechnology Demonstration System (BDS); ESA Biopack (eight experiments); Application of Physical & Biological Techniques to Study the Gravisensing and Response System of Plants: Magnetic Field Apparatus (Biotube-MFA); Closed Equilibrated Biological Aquatic System (CEBAS); Commercial ITA Biological Experiments (CIBX); the Microbial Physiology Flight Experiments Team (MPFE) experiments, which included the Effects of Microgravity on Microbial Physiology and Spaceflight Effects on Fungal Growth, Metabolism and Sensitivity to Antifungal Drugs; Osteoporosis Experiment in Orbit (OSTEO); the Physiology and Biochemistry Team (PhAB4) suite of experiments, which included Calcium Kinetics, Latent Virus Shedding, Protein Turnover and Renal Stone Risk; Sleep-Wake Actigraphy and Light Exposure During Spaceflight (SLEEP); and the Vapor Compression Distillation Flight Experiment (VCD FE).

Selected by NASA in April 1996, Clark was making her first spaceflight.

Click Here For The Shuttle Columbia Memorial

Dr. Jonathan Clark’s Special Message to Scholastic News Teachers

Astronaut Laurel Clark’s husband Jonathan writes to Scholastic News teachers.

Dear Teachers,

From the Editor in Chief

Dear Teachers,

Our March issue of Scholastic News featured an article entitled “My Mom Is an Astronaut,” about Columbia Mission specialist Dr. Laurel Clark and her son, Iain. After the space shuttle disaster on February 1, we sent you a letter recommending that you not use the issue in your classrooms. Since then, we have been in touch with Dr. Jonathan Clark, Laurel’s husband and Iain’s father. After reading the article, Dr. Clark was so moved by the issue that featured his wife and son, he was inspired to write this letter to you.

We’re honored to be able to share Dr. Jonathan Clark’s heartfelt letter with our Scholastic News teachers. You may want to share his thoughts and insights with your students, if you think the article is appropriate for your classroom.

Sincerely,

Rebecca Bondor

Editor in Chief

Scholastic Classroom Magazines

My wife, Laurel Clark, and our son, Iain, wrote the article called “My Mom Is an Astronaut” in the March 2003 Scholastic News. As many of you may know, the space shuttle Columbia (STS 107 mission) broke apart in the upper region of the Earth’s atmosphere on the morning of February 1, 2003. The crew and their space shuttle were all lost in an instant. Fortunately, they did not suffer, and in their last moments they were probably all thinking of the wonders of space after a very successful 16-day mission, and looking forward to seeing all their friends and family back on Earth.

My family hopes that you will consider using this Scholastic News issue in your classroom, even though this may remind everyone of this great loss. Laurel loved children and education was her passion. She would have wanted children to see this article as well.

The many teachers in our family showed me the precious cards from their students. We were all overcome with how much expression and creativity was generated by young minds in the face of the tragedy. Although we were all deeply saddened that Laurel and her crew were lost, it was a special joy to know that their legacy was not lost. In the hour after the shuttle was lost, astronaut and teacher Barbara Morgan comforted me with the words “our children will get us through this.” Although at the time I doubted it, I have to say she was right. My son, Iain, and the other Columbia kids gave us strength beyond our imagination.

Life is fragile and so precious, and sometimes a loss like this allows us to look at it differently. As far as risk and danger are concerned, life has many ups and downs. We could never have discovered new places and things without some risk. We can do what we can to reduce risk, like wearing a seatbelt in a car, or wearing a helmet while riding a bike, but we will still do those things. What makes us alive often involves some risk. One of Laurel’s favorite quotes was: “A ship in harbor is safe—but that is not what ships are for.”

Although this was a terrible loss for my son and me, as well as the rest of the Columbia families, and the nation and the world, we felt extremely proud that Laurel was an astronaut whose mission was to help make new discoveries to help humankind. So many emotions and issues are tied with this article now: sadness and hope, exploration and discovery, challenge and risk, to name a few. It is now up to the educators and parents to pass this spirit on to our legacy and future, our children.

Jonathan B. Clark M.D.

The Love of Their Lives

31 January 2004

Courtsy of the Los Angeles Times

“We were buddies and everything,” he said. “But I was on the sidelines. He just worshipped his mom.”

Then, just like that, she was gone.

Laurel Clark, a Navy Captain and Astronaut, was killed one year ago Sunday when the space shuttle Columbia ripped apart over Texas. Today, Jon, 50, and his only son, 9-year-old Iain, are partners. Death has brought them closer.

“We both lost the love of our lives,” Jon said Thursday at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. “That is our bond. And it is very special.”

It has been a year of heartbreak and regret, of endless funerals and memorials and visits to the psychologists.

Jon has met with survivors of the astronauts killed aboard the space shuttle Challenger, which exploded in 1986. Their message, he says, was clear: Don’t expect the pain to end.

Iain still feels, in a sense, betrayed, bewildered as to why his mother didn’t take his advice and just stay on Earth.

“Some days he doesn’t say much, doesn’t let a lot out,” Jon said. “There are days when I’m barely holding up myself.”

In the end, though, they have found a glimmer of optimism. As Jon has struggled with the practical realities of being a newly single parent — Where was it that Iain had gotten his haircut all these years? — he and his son have become, in some ways, equals.

Jon has become a reluctant crusader at NASA, where he is involved with the shuttle program, calling for reform of an inflexible culture that he believes contributed to the accident. He uses his campaign to teach Iain lessons about foresight, about mistakes and consequences.

The boy, in turn, has taught Jon a thing or two about looking beyond the stats. What the surgeon might have seen as youthful delusion — Iain’s efforts to “fix” his mother’s death — the father now sees as a ray of hope. Iain has suggested, among other things, building a time machine so he can warn his mother not to board the shuttle. He has attempted to create magic potions that might bring her back. He also thinks it might be a good idea to try to clone her.

“He has a tenderness and a perception that adults are not even close to understanding,” Jon said. “He is openly trying to get his arms around this, and it’s very heartening to me. What a marvelous little brain.”

When it was pointed out that Iain’s ideas are fanciful, that some things just hurt and can’t be changed, Jon offered a tired smile, as if recognizing, and now dismissing, such grown-up cynicism.

“You never know,” he said with a shrug. “I wouldn’t put it past him to build a time machine one day. Maybe he really will bring her back.”

It was a cool game, one you can only play when you’re 8 and your mom is a real-life astronaut.

“Earth to mom!” Iain would yell, galloping through the tidy brick house at the end of a cul-de-sac, the one with twin magnolias out front and a ceramic rabbit in the garden. “Space to Iain!” Laurel would reply. Iain would laugh, and mimic the static of a radio transmission, then break into a wide smile that could have been lifted right from his mother’s face.

Deep down, though, as the Columbia mission approached, it became clear that Iain did not want her on that spaceship, not now, not ever. He was sure that if she flew into space, she would not make it home.

Laurel, who was accepted into the astronauts’ corps in 1996, somehow managed to do it all, juggling her duties as a mother with those of an astronaut. It was she who planted flowers in the yard, who helped Iain with his artwork. Jon frequently worked long days. It was expected at NASA, but today he realizes that it added up to a subtle distance between him and Iain, and that it may have contributed to Iain apprehension about Laurel’s mission.

Launch day came January 16, 2003.

“If you’ve ever seen a launch, it’s really remarkable,” Jon said. “Sound travels slower than light. So you see it first, just rising straight up. And then you feel it, feel the energy, in your chest.”

The crowd cheered as Columbia soared toward space. Iain wept.

“He was crying and crying,” Jon said. “He was so sad, you’d have thought he had smashed his toe. He had some sort of premonition. I really believe that. He felt like she was leaving him. Not leaving him like she was going to come back soon. Leaving him. Forever.”

It was Laurel’s first time in space. Once in orbit, she wrote to her family and friends that she was becoming personal friends with Orion, the hunter whose constellation — particularly the three stars that form his belt — is among the most recognizable in the night sky. She talked with Jon and Iain regularly through private videoconferences, describing her involvement in several experiments, such as a test of antibiotics in low gravity. Jon took short videos of Iain and e-mailed them to her.

“She was exuberant,” Jon said.

Iain just wanted her home.

“I want to snuggle with you in my fort,” he wrote to her in an e-mail a few days before the shuttle was scheduled to land in Florida. Jon watched him type the message slowly, searching for each letter with his index finger. “Come home soon or sooner if possible,” Iain wrote. “I miss you millions more than all the stars in the universes. I love you so much I cried last night.”

The morning the shuttle was expected to return, Laurel played a CD of an ancient bagpipe song to wake up the crew. The song ends: “Love sets the heart a-dreaming / Longing and dreaming for the homeland again.” The crew put away the trash — an important step when one is preparing to descend back into gravity — and strapped in.

Jon and Iain walked outside the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to wait with the other families for the shuttle to land. The adults were buzzing with anticipation. The seven astronauts had 12 children among them, and many of the kids were there, playing under the bleachers. The static of radio transmission echoed across the tarmac, projected by two speakers.

“Columbia. Houston.” It was NASA’s mission control, trying to talk to the crew. “We see your tire pressure messages.”

Something was wrong. Sensors aboard the shuttle indicated that its tires were failing.

Jon was not an astronaut but he was intimately familiar with how the shuttle worked, and he knew that instant that the shuttle — which could not land safely without wheels — was in trouble.

It was Jon who had been the voice of caution back in 1994, when Laurel applied for the astronauts’ corps. She was eight months pregnant with Iain at the time. Being an astronaut is risky business, he told his wife. People have died, he told her mother. Stop being ghoulish, he was told.

As the radio transmissions continued, the rest of the crowd continued to celebrate. Within minutes, NASA reported that it had lost contact with the crew. Television reports began streaming in to the space center, showing pieces of the craft streaming across the sky.

NASA cut the transmission. At 41 years old, Laurel was dead.

“I didn’t want her to go,” Iain told his father not long after the accident. “She went anyway. And now I don’t have a mom.”

Flipping channels one recent day, Iain came across a program about the accident. It focused on a NASA safety engineer who had warned during the mission that a piece of foam insulation that fell from an external fuel tank might have harmed the shuttle. The engineer sent an e-mail to his colleagues saying that NASA was treating tough questions about safety like “the plague.”

Investigators later determined that the insulation, initially discarded as a potential problem, ripped the wing and allowed superheated gas to penetrate and destroy the craft.

“Why didn’t they listen?” Iain asked his father.

“I told him that it’s like when your teacher tells you not to do something, and then something bad happens because you didn’t listen,” Jon said. “NASA was like a child that didn’t listen. It was a very poignant reminder for him. It’s important to listen. You don’t have to make the mistake to see the consequences. You can think about things that might happen instead.”

This weekend will bring another round of memorials and ceremonies. The astronauts are expected to be honored during Sunday’s Super Bowl in Houston. On Monday, a memorial to the crew will be dedicated at Arlington National Cemetery — where Laurel is buried — next to a similar Challenger memorial.

Jon is planning to head to the dense, shady woods of East Texas.

It was there that some of Laurel’s belongings fell from the sky — a piece of a James Taylor CD, a soot-covered medallion from the University of Wisconsin, where she received her medical degree. He still hasn’t decided whether to take Iain along. Best, perhaps, to leave him with relatives, to leave him unaware of the significance of anniversaries for now.

“It’s a tough time,” he said. “I just don’t know. Maybe next year.”

January 30, 2004

Astronaut’s husband wishes whole family had died in pre-Columbia

Courtesy of the Associated Press

CAPE CANAVERAL, Florida (AP) — Even in his not-so-dark moments, Jon Clark wishes they had all died in that plane crash in West Texas. Then they’d all be together now — he, his wife Laurel and their son, Iain. And the six other Columbia astronauts would still be alive.

“I’ve lamented about that, wishing that we had all just died because then it would have changed the course of history. They wouldn’t have launched,” Clark said in a telephone interview from Houston on a dreary January day that marked the anniversary of the space shuttle’s doomed liftoff.

Laurel Clark — his wife, best friend, NASA colleague and the mother of 9-year-old Iain — was aboard Columbia when it fell from the Texas sky in pieces last February 1.

Just six weeks earlier, in December, all three Clarks had plummeted from the sky over the same state in their single-engine Beech Bonanza. They were flying from their home in Houston to Albuquerque, New Mexico, to spend Christmas with Laurel’s family.

The plane hit strong turbulence over West Texas and, for the first time ever, Laurel got air sick. Jon Clark was trying to land when the plane got caught in a downdraft. In a flash, the stall warning went off and the craft was sucked down, careered off the runway and smashed into an embankment.

The plane was damaged beyond repair. But the Clarks walked away.

Three weeks later, Iain was afraid to get on a turboprop to fly to Cape Canaveral for his mother’s launch. The propellers frightened him.

The plane crash also may have exacerbated his dismay about his mother’s first shuttle flight. Iain cried at the launch and badgered her for leaving every time they talked during the private family radio hookups during the mission, his father recalls.

Clark wonders whether his son had a premonition.

He says his wife traveled often and had even been sent to Russia, so it wasn’t just the separation between mother and son that bothered the child. “There was something different about this. It is spooky,” he says.

In the long days and weeks and months since that gut-wrenching February morning, Clark has agonized over the crew’s final seconds a thousand times, trying to figure out what his wife and the other astronauts may have been doing and how long they may have lived.

He wants NASA to talk openly about all the circumstances surrounding their deaths, in order to learn and benefit future space crews. The cabin remnants, stored at Kennedy Space Center along with the rest of the wreckage, have been off-limits to all but a handful of cleared personnel. Details are sparse.

“You’ve got to be out in the open about it,” says Clark, a NASA flight surgeon and neurologist. “You’ve got to say, ‘How did this thing come apart? How did the crew die?'”

He’s also insistent — even obsessed — that the space agency’s lingering safety culture woes be addressed.

Accident investigators came down hard on a NASA bureaucracy that ignored the chronic problem of breaking fuel-tank foam insulation and then allowed engineers’ worries to be buried while Columbia was aloft.

Clark nags NASA’s boss, Sean O’Keefe, every chance he gets.

“He’s very deferential,” Clark says. “I also realize that actions speak louder than words and I don’t want to hear about it. I want to see it.”

The 50-year-old Clark remains at NASA only because he feels he can better initiate change from within. Of all the Columbia astronauts’ immediate family members, he is the only one who works for the space agency and often speaks on behalf of the others at public events.

His psychiatry training comes in handy dealing with his son, but it’s not enough.

“I am not a child grief person,” he says. “That’s why instead of soccer games, we go to the psychologists in the afternoons.

“He’s gone through that denial-bargaining phase where he’s trying to invent a time machine to go back and warn her, or clone her.”

Laurel Clark’s death at age 41 has brought father and son closer together and provided some precious intimate moments. “But then we also have to contend with no mom, no wife, nobody to goof off and have fun with, camping or hiking or all of the things that we loved to do together,” he says quietly.

Every so often, Iain asks his father, “Why didn’t they listen to that engineer?”

He’s talking about the engineer at Johnson Space Center in Houston who feared Columbia might be gravely wounded but did not express anything to the right people at the top and who kept silent at the mission management meeting where the topic was put to rest.

The question breaks the father’s heart.

“Well, you know, honey,” he gently tells Iain, “it’s like at school when you don’t listen to the teacher and she really knows that this is the thing you need to do to not get hurt, but you don’t listen. That’s kind of like what NASA is doing. They’re the child that doesn’t listen to somebody who might know better.”

On the Net:

Arlington National Cemetery

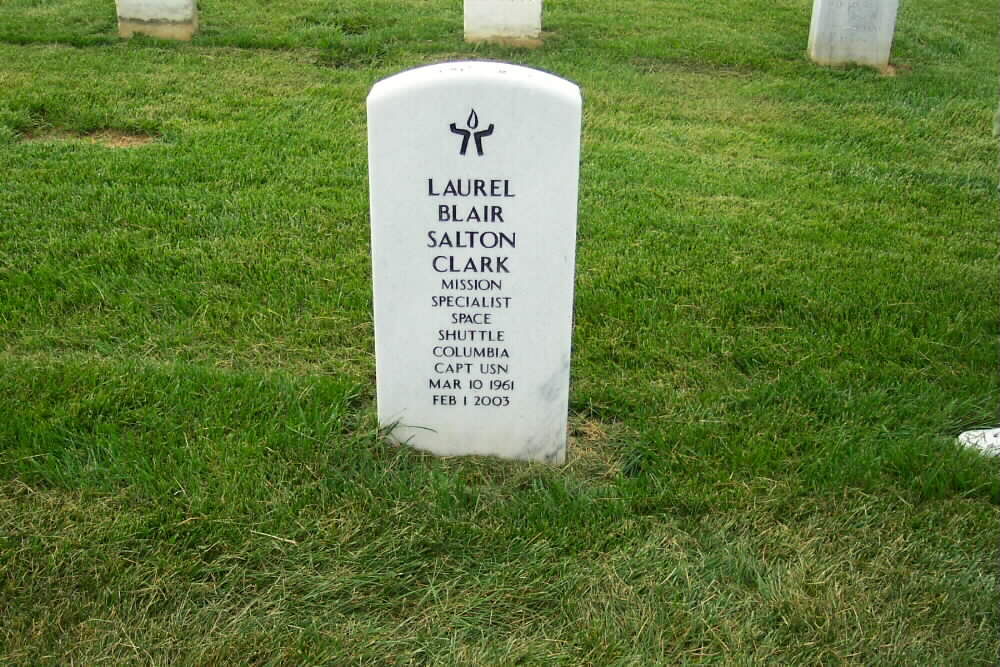

CLARK, LAUREL BLAIR SALTON

CAPT US NAVY

- DATE OF BIRTH: 03/10/1961

- DATE OF DEATH: 02/01/2003

- BURIED AT: SECTION 46 SITE 1180-2

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Her husband and their 8-year-old son would sprint past her in a race to the mountaintop,

and Laurel Blair Clark would amble behind, absorbing each smell and sight nature could

offer in the hikes she loved to take.

“She knew the journey was more important than the destination,” Jon Clark recalled at her funeral Monday.

Laurel Clark’s final journey ended February 1, 2003, aboard the Columbia space shuttle, but not before she flashed a wide grin for the shuttle camera to show the world “she was loving life,” her husband said.

On what would have been her 42nd birthday, Clark was laid to rest with military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. She will be buried beside two other Columbia crew mates and just a few feet from where the unidentified remains of Challenger astronauts are interred beneath a granite memorial.

Blustery winds ruffled the American flag draped atop Clark’s coffin as it was taken by caisson to the cemetery. The graveside service began with a “missing man” formation flyover, in which one of four jets that roared above the crowd peeled away, soaring high out of sight into the nearly cloudless sky.

As the U.S. Navy (news – web sites) Band played “America the Beautiful” and the honor guard folded the flag, Clark’s husband leaned over to their son, Iain, and helped place the boy’s right hand over his heart.

When an admiral leaned in toward him to offer his condolences, the boy reached up and fingered the shiny medallions dangling from the officer’s uniform.

Iain rose quietly with his father, and each placed a single pink rose on top of Clark’s silver casket. He squeezed his dad’s hand when emotions threatened to brim into tears.

Clark worked as a submarine doctor for the Navy before she joined NASA in 1996. She was born in Iowa but grew up in Racine, Wisconsin, which she considered her hometown. She lived in the Houston area with her family before the fatal space mission. The Columbia flight was her first assignment in space.

Top military officials, along with NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe, posthumously awarded Clark three medals for her distinguished service to her country, including her research into links between prostate cancer and bone cells.

A bagpiper played a Scottish melody and a cold wind swept flowers from the grave site during a memorial service yesterday at Arlington National Cemetery for astronaut Dr. Laurel Blair Salton Clark who died during the explosion of Space Shuttle Columbia.

NASA officials said the song — “Scotland the Brave” — was the one Captain Clark played to awaken her seven crew mates February 1, 2003, when the shuttle disintegrated over Texas, just 16 minutes from a safe landing in Florida.

The graveside service began yesterday with four Marine F-18 jets swooping over the cemetery’s Memorial Amphitheater. One flew at an angle to show the message: “Fly-By, Missing Man Formation.” Three U.S. flags and three medals honoring Captain Clark were presented to her family while more than 70 sailors stood at attention and about 200 family members and friends watched in their winter coats. One of the flags had flown at half-staff over Johnson Space Center in Houston since the Columbia disintegrated. Presenters said Captain Clark “far exceeded expectations” and that accomplishments “contributed significantly” to advancements in spaceflight.

Nearest to Captain Clark’s flag-draped casket were husband Dr. Jonathon Clark, also in the space program, and 8-year-old son Iain. Captain Clark was five months pregnant with Iain when the National Aeronautics and Space Administration selected her to train for a mission in space.

The service included six of Captain Clark’s 1996 NASA classmates as honorary pallbearers: Joan Higginbotham, Sandra Magnus, Lisa Novak, Julie Payette, Heidemarie Stefanyshyn-Piper and Stephenie Wilson. The service also included the Navy Band playing taps and “America the Beautiful.” Seven sailors fired a 21-gun salute.

NASA and military technicians are still searching in New Mexico, Texas and the Gulf of Mexico for more clues to learn how the shuttle fell apart upon returning to Earth after 16 days in flight.

Captain Clark’s father, Robert Salton, 69, a farmer and carpenter living near Albuquerque, New Mexico, had gone outside the Saturday morning of the crash after hearing news that the Columbia would be passing overhead.

Newscasts minutes later informed him about the disaster.

Waiting in Florida for Captain Clark were her sister, Lynne Salton, of Kansas City, Missouri, and Captain Clark’s son and husband who had been living in Houston during her training.

Captain Clark was born in Iowa, spent childhood years in New Mexico, then moved to Racine, Wisconsin, with her mother, Margory Brown, after her parents divorced.

Her father has said Captain Clark received straight A’s at William Horlick High School before earning a scholarship that enabled her to earn a bachelor of science degree in zoology from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1983 and a doctorate in medicine in 1987 from the University of Wisconsin.

She continued her training during the 1980s, including assignments as an undersea medical officer trainee. She got a taste of Scottish music when she was assigned to Submarine Squadron 14 in Holy Loch, Scotland.

Captain Clark enjoyed scuba diving, hiking, camping, biking, parachuting, flying and traveling. Her training and duties also took her to Arizona, Connecticut, Florida and the western Pacific.

Captain Clark had three Navy Commendation Medals, a National Defense Medal and Overseas Ribbon before additional awards were given yesterday to her family.

Assistant Navy Secretary Dionel Aviles presented the family with the Defense Distinguished Service Medal. NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe presented the agency’s Distinguished Service Medal and retired Marine Col. Robert D. Cabana, also director of flight crew operations, presented the NASA Spaceflight Medal.

Captain Clark was also posthumously promoted from the rank of Commander.

After burial services, Dr. Clark, Iain, other family members and friends walked up to the casket and placed roses on it. One woman kissed the palm of her hand and held it on the casket for several seconds.

Seventeen other astronauts, dating back to 1964, are buried in Arlington.

The unidentified, commingled remains of seven astronauts who died on Space Shuttle Challenger on Jan. 28, 1986, are also interred in Arlington.

Celebrating an Explorer’s Life

Astronaut’s Passion Recalled at Funeral

By Timothy Dwyer

Washington Post Staff Writer

Tuesday, March 11, 2003

They walked hand in hand, father and son, at a steady pace under a cloudless blue sky. While a stiff breeze snapped flags to attention, Jon Clark took his 8-year-old boy, Iain, for one last walk with his mother.

Ahead of them was a horse-drawn caisson carrying her flag-draped coffin, and behind them was a contrail of family, friends and mourners who had come to say goodbye to Laurel Blair Salton Clark, one of the seven astronauts who died February 1, 2003, aboard the space shuttle Columbia.

They buried her at Arlington National Cemetery yesterday on what would have been her 42nd birthday — next to one of her crew mates, Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Michael P. Anderson. A third Columbia crew member, Navy Captain David M. Brown, will be laid to rest tomorrow at the same site.

Before yesterday’s solemn procession along the narrow cemetery lanes, Jon Clark delivered his wife’s eulogy at a service held in the Memorial Chapel at Fort Myer. His remarks mirrored her life — filled with passion, promise, love and humor.

She was an explorer of the first order; a submarine officer, a diver, a helicopter pilot, a medical doctor and, her last job, a mission specialist performing scientific experiments on her first shuttle flight.

Jon Clark said that explorer mentality was present even during simple family hikes: While he and Iain would race to the top of the trail, Laurel would invariably stop along the way, more interested in the journey than its end.

From her family, he said, she learned compassion and acquired her thirst for knowledge and realization of the importance of family and friends. What she learned from him, he said, laughing, was tolerance.

“I used to say that I was like the sand in an oyster,” he said, as those filling the chapel laughed gently, “and she would make a pearl out of me.”

Laurel Salton was born in Iowa but called Racine, Wisconsin, home. She was the oldest of four, two girls and two boys. Her parents, Margory and Robert Salton, were divorced when she was a teenager. Her mother later married Richard Brown, who had five children of his own, and the family moved to Racine in 1975.

Jon Clark is also a Navy Commander and NASA flight surgeon. The couple met at dive school, and he asked her to marry him while they were stationed in Scotland. They were wed in 1993 and, when their son was born, they named him Iain in honor of her Scottish roots.

She joined the Navy after college because she wanted to go to medical school and, with three siblings and five step-siblings, there wasn’t much money.

The Navy got much more than a doctor in the deal. Clark became an undersea medical officer, dove with the elite Navy SEALs, became a flight surgeon and, later, an astronaut.

“When she applied to become an astronaut,” her husband recalled, “I asked her what she would do if she didn’t get in. And she said she would be a stay-at-home mom. They were both great jobs!”

Six women from her 1996 astronaut class served as honorary pallbearers yesterday.

“Columbia was a proud spacecraft,” Jon Clark said. “She came to know and love her fellow crew mates . . . as if they were brothers and sisters.”

Among the messages his wife sent home from space, he said, was this one: “Hello from above our magnificent Earth. Let me beam good, positive energy to all who I love.”

He recalled how he chose her “wake-up” music for the Columbia voyage; on the final morning of her life, she awakened to the stirring strains of “Scotland the Brave.” Yesterday, as the mourners placed farewell roses on her coffin, a bagpiper played.

Laurel Clark loved the outdoors, her husband recalled, which made the family’s final walk yesterday all the more poignant. They arrived at the grave site about noon. There was a flyover of F-18s from U.S. Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 321. The Navy Band played “America the Beautiful.”

The father sat next to the son, the coffin in front of them. They were presented with three medals honoring Laurel Clark’s service to her country.

Jon Clark said his wife would have wanted U.S. space exploration to continue, despite the Columbia tragedy. The loss of its crew, he said, should serve as an inspiration for exploration.

Clark said his wife recognized the inherent danger. “She used to say, ‘A ship in the harbor is safe, but that is not what ships are for,’ ” he said, referring to her favorite quote.

The funeral procession for Navy doctor and Astronaut Captain Laurel Blair

Salton Clark arrives at Section 46, where she and two other crewmembers of the

Columbia space shuttle are to rest beside each other. Trailing the caisson are the Navy

funeral detail, honorary pallbearers and Clark’s husband, Dr. John Clark, and son Iain, 8.

(Photo Courtesy of the Military District of Washington)

An Army Caisson And A Navy Honor Guard Escort Captain Clark’s

Casket To It’s Burial Spot In Arlington National Cemetery.

A Navy Honor Guard Team Carries The Casket of Captain Clark

Past The Shuttle Challenger Monument To It’s Gravesite At

Arlington National Cemetery

Captain Clark’s Husband, Jonathan Clark, and her son, Iain, 8, stand while

the flag from her casket is folded.

Jonathan Clark and his son, Iain, receive folded flags from

Captain Clark’s casket.

Jonathan and Iain Clark receiving the flags which covered Captain

Clark’s casket.

Jon Clark, husband of Space Shuttle Columbia astronaut Laurel Clark, and son Iain, 8, hold hands and cling to a folded flag during her funeral at Arlington National Cemetery March 10, 2003

Jonathan Clark, widower of space shuttle Columbia astronaut Laurel Clark, is consoled as he sits

beside his wife’s casket during a graveside service with full military honors at Arlington National

Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia., Monday, March 10, 2003.

Iain Clark bids a final good-bye to his Mother.

Flowers are placed on the casket of NASA Astronaut and Navy Captain Laurel Blair Salton

Clark, a member of the space shuttle Columbia crew, at Arlington National Cemetery in

Arlington Virginia, Monday, March 10, 2003. Clark was laid to rest near the memorial,

at right, which honors the astronauts from the space shuttle Challenger.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard