NEWS RELEASES from the United States Department of Defense

No. 030-06 IMMEDIATE RELEASE

January 11, 2006

DoD Identifies Marine Casualties

The Department of Defense announced today the death of five Marines who were supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom:

- Lance Corporal Kyle W. Brown, 22, of Newport News, Virginia

- Lance Corporal Jeriad P. Jacobs, 19, of Clayton, North Carolina

- Lance Corporal Jason T. Little, 20, of Climax, Michigan

- Corporal Brett L. Lundstrom, 22, of Stafford, Virginia

- Lance Cpl. Raul Mercado, 21, of Monrovia, California

All five Marines died on January 7, 2006.

Mercado was killed when his vehicle was attacked with an improvised explosive device while conducting combat operations near Al Karmah, Iraq. He was assigned to 2nd Maintenance Battalion, 2nd Marine Logistics Group, II Marine Expeditionary Force, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Little was killed when his tank was attacked with an improvised explosive device while conducting combat operations near Ferris, Iraq. He was assigned to 2nd Tank Battalion, 2nd Marine Division, II Marine Expeditionary Force, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Brown, Jacobs and Lundstrom were killed by enemy small arms fire in separate attacks while conducting combat operations near Fallujah, Iraq. They were assigned to 2nd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division, II Marine Expeditionary Force, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Family takes comfort in slain Marine’s love for service

By KATE WILTROUT, T

Courtesy of The Virginian-Pilot

January 10, 2006

Rodney Bridges was asleep Saturday afternoon when four uniformed Marines came calling at his Poquoson home. His 12-year-old son, Daine, let them in, excited they might be friends of his beloved older brother.

Instead, the men delivered the news every military family dreads: Bridges’ eldest son and Daine’s brother, Private First Class Kyle W. Brown , had been killed Saturday in Iraq.

“He was 100 percent Marine. That’s what he always wanted to do, and that’s what he did,” Bridges said Monday.

The 22-year-old , a 2002 graduate of Newport News’ Heritage High School , was no stranger to combat. It was his second tour in Iraq. He served with Echo Company, 2nd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment from Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Bridges, who did a hitch in the Army, said his son grew up dreaming of military service and was especially impressed with an uncle who had served multiple tours in Vietnam as a Marine. At Heritage, Brown enrolled in the junior reserve officer training corps, or JROTC. He headed to Parris Island , South Carolina, weeks after receiving his diploma.

“When he went to boot camp, with his size, a lot of people didn’t think that he could make it,” his father said. “But in hand-to-hand combat, his instructor told us, he cleaned house.”

Quiet, with a wiry body that was two inches shy of 6 feet, Brown’s physique didn’t scream “Marines,” said retired Navy Cmdr. Tom Smith , a JROTC instructor at Heritage.

Still, Smith remembered him as a model cadet who returned to the school after making it through basic training to talk to the other students. He visited Smith again after his first tour in Iraq in 2003.

“He’d seen a lot of action, been in a lot of tough fighting,” Smith said. “He was still the same quiet guy. He was more serious.”

Bridges, 43 , takes some comfort from knowing that Brown died doing what he loved. During his 3½ years in the military, Brown was deployed more than he was home. He participated in the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and did a tour in Afghanistan. He trained in Japan and Korea, served for a few months in Africa, and helped the Philippines’ military fight al-Qai da forces in that island nation, Bridges said.

Brown trained as an assaultman, his father said, specializing in anti-tank and anti-personnel missions that can require close combat. He also carried the squad automatic weapon.

Since Brown was killed, Bridges has heard repeatedly about what a good Marine his son was. A friend of Brown’s in Iraq – a guy who co-signed the loan for Brown’s new Yamaha motorcycle – wrote to say that Brown had made life more enjoyable and that he always tried to do the right thing, even when that was impossible.

The details of Brown’s death in Fallujah are still murky. The Marines told Bridges that his son was felled by light arms, probably a pistol or a rifle, and they suspect a sniper may have targeted him.

The family is waiting for Brown’s body to arrive in the United States . They recounted the last time they were together before Brown’s unit deployed in September.

Hotels outside Camp Lejeune were booked solid; the family shared a room that had only one bed. Brown slept on the window seat. “It’s better than a sand trap underneath a tank,” Bridges remembered his son saying .

The next day, older and younger brother enjoyed some last-minute horseplay. Father and son traded “I love yous” through an open car window.

Brown shielded his father from a nagging feeling about the upcoming deployment. Bridges said that only lately did he learn that Brown told his father’s fiancee, Carolyn Byrd , he didn’t have a good feeling about his second tour in Iraq.

The news has been especially difficult on Bridges’ mother, Bridges said; Brown lived with his paternal grandmother in downtown Newport News during high school.

Bridges’ sister brought their mother – a cancer survivor who had surgery last week – to Bridges’ house in Poquoson to break the news.

She pounded Bridges on the chest, insisting it couldn’t be true. Later, she fainted and fell, ripping open her incisions and requiring an ambulance ride to the hospital, Bridges said.

Bridges said his son will be interred with military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. Services are pending. Those wanting to remember Brown are asked to make a contribution in his name to the American Cancer Society.

“You don’t ever plan on burying your children,” Bridges said. “Kyle died, and he died in one of the better ways – in the service of his country, so we can enjoy the liberties we have.”

Lanky Teen Driven to Become a Marine

Iraq Casualty Known As Patriotic, Serious About the Corps

By Nikita Stewart

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Thursday, January 12, 2006

As a teenager, Kyle W. Brown was always long and lanky — a little too slight to be a Marine, despite a high school career in the Navy Junior ROTC, said his grandmother, Katheryn Brown.

“They said, ‘You’re too skinny to be a Marine,’ ” recalled Brown, 68. “He worked out hard for a year and a half and beefed up.”

In July 2002, the Newport News, Virginia, teenager realized his ambition.

Last Saturday, Lance Corporal Kyle W. Brown, 22, was fatally shot in the head by a sniper in Anbar province near Fallujah, according to the account his grandmother said Marine Corps officials gave the family. It was his second tour of duty in Iraq.

An official news release from the Department of Defense said Brown was killed “by enemy small arms fire” near Fallujah. Lance Corporal Brett L. Lundstrom of Stafford was killed in a separate attack in the same area that day, according to the release. A spokesman for the 2nd Marine Division, First Lieutenant Barry Edwards, said that was all the information he had.

Brown and Lundstrom were assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division, 2nd Marine Expeditionary Force, based at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Brown was raised in Newport News and lived with his grandmother. He went to Heritage High School. He had a crooked smile and was so mild-mannered that his grandmother called him “Casper.”

“You know, like the friendly ghost,” she said during a phone interview.

Growing up, he loved ramen noodles, which he called “Roman noodles,” and WarHeads sour candy. “They would light your head up. He used to like to slip me one and look at my face,” Brown said.

“He was also silly. You know how teenagers can be silly,” she said. “He’d come down and sit at the breakfast table in his underwear with those chicken legs. I’d say, ‘Hey, put some pants on.’ ”

But Kyle Brown was serious about the Marines. “He kept his hair cut short,” his grandmother said.

When he finally bulked up enough to make the cut and enlist, he said, “How do you like me now? I’m a Marine,” Brown recalled.

She said her grandson was unusually patriotic, although he was hesitant about returning to Iraq after he left in September, she said. “First of all, we are Americans. Freedom is not free,” she said.

The family hopes to have visitation this weekend in Poquoson, Virginia, and will have a funeral at 1 p.m. Tuesday at Arlington National Cemetery, Brown said.

Kyle Brown earned several commendations and medals, including the Iraqi Campaign, Global War on Terrorism Service and National Defense Service medals, Edwards said. Brown had been with the 2nd Battalion since February 2003, he said.

Lundstrom, 22, received medals for the Iraqi Campaign, Afghanistan Campaign, Global War on Terrorism Service and National Defense Service. He joined the Marines in January 2003, Edwards said.

His family could not be located for comment.

A family mourns a fallen Marine

Kyle Brown’s father has slept little since his son was killed in Iraq. Now, support is pouring in.

BY JIM HODGES

Courtesy of the Daily Express

January 14, 2006

The hardest part was a week ago, when four Marines stood in front of the fireplace in Rodney Bridges’ living room and told him the news.

Or maybe it was Friday night, when his son came home in a flag-draped casket.

Or maybe it’s yet to come, on Monday when “Amazing Grace” is played at his funeral in Poquoson.

Or Tuesday, when seven rifles fire three shots each to punctuate the service in Arlington National Cemetery.

It’s been hard every day at 4 a.m. for Rodney Bridges since he learned that son Kyle Brown, 22, had been killed by a sniper while on patrol at Fallujah, Iraq, on January 7, 2006.

“I get up early,” Bridges says. “I don’t sleep much, and then I take a shower.

“That’s when I bawl.”

And then he adjourns to a bedroom and turns on the computer to see what e-mails have been posted on the Marine family Web site during the night. Into Friday, there had been 75, most from other parents offering sympathy. Many elicit more tears.

“He’s at that thing all day and all night,” says Carolyn Byrd, Bridges’ fiancee. “When he’s not out, he’s at the computer.”

The day and often the night are broken by telephone calls from around the country, even from around the world.

One was from the mother of Joe Kowalichick, a Marine who was with Brown in Iraq.

“She said that he was having problems, that he couldn’t sleep, thinking about it,” Bridges says. “She said he couldn’t do anything. That he couldn’t concentrate.”

Then Kowalichick himself called, one of three Marines who have contacted Bridges from Iraq.

“I told him, ‘Joe, you’ve got to talk to somebody, a Chaplain, your First Sergeant, somebody,’ ” Bridges says. “You’ve got to be able to concentrate. We don’t want any more body bags back here.”

Other calls come from Marines who are dealing with details: the casualty officer about the logistics of getting Brown back from Iraq; choosing the casket; paperwork concerning money and medals; the budget for the funeral; reading a medical report of the incident.

Or from other people wanting decisions: When is the funeral? Where? How do we get to Arlington?

Bridges has learned that support is everywhere.

“I was at the store, buying a suit, and the man selling it there was from Israel,” Bridges says. “He said he knew about first-borns, how important they were. And then he prayed with me.”

A telephone call Friday helped.

Rich Schumann lost his Marine son near Fallujah almost one year ago. He and his wife, Mary, have been learning to cope ever since.

“That first contact, those words, you don’t ever forget them, ever,” Schumann says of the visit from the Marines to tell him that Darrell was dead.

Two fathers who have never met but who know each other’s pain.

Flowers and plants are delivered. Pictures are being assembled for a collage.

Another Bridges son, Daine, tells them of questions he gets in sixth grade. He can’t answer many of them.

“He’s in denial,” Bridges says.

They all cope with stories, some of them bringing gales of laughter, such as the one about the aerosol cans that exploded when they were accidentally thrown into a trash fire.

“You heard a BOOM,” Bridges says, laughing.

“And then you saw him run,” adds Katheryn Brown, a cancer patient who learned of her grandson’s death only a day after undergoing surgery. She’s laughing, too.

“I told him, ‘There, you can see what can make a Marine run.’ ”

Then the tears return.

The weekend ahead is daunting.

“The finality of it all,” Bridges says, then stops, overcome.

That finality, that’s the hardest part of all.

Soldier, Marine From Va. Get Final Salute at Home

Captain and Corporal Killed in Iraq Are Buried at Arlington

By Lila de Tantillo

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Wednesday, January 18, 2006A dreary gray sky set the scene as two Virginians who were killed in Iraq were laid to rest yesterday at Arlington National Cemetery.

Army Captain Christopher P. Petty, 33, of Vienna and Marine Lance Corporal Kyle W. Brown, 22, of Newport News were the 214th and 215th people killed in Operation Iraqi Freedom to be buried at Arlington.

- A caisson bears the body of Army Capt. Christopher P. Petty, 33, of Vienna at Arlington Cemetery

The morning drizzle let up just as the horse-drawn caisson bearing Petty’s coffin approached the grave site. About 100 mourners followed the full-honors procession, which included a band and an escort that accompanied the coffin on foot from the Old Post Chapel at Fort Myer.

Petty was among five soldiers killed January 5, 2006, in Najaf when an improvised explosive device detonated near their Humvee.

The band played “America the Beautiful” as the honor guard carefully folded the American flag draping the silver coffin. Brig. Gen. David Anthony Morris presented the flag to Petty’s widow, Deborah. The soldier also leaves behind sons Oliver, 3, and Owen, 3 months.

Petty, who was born in Berlin and grew up overseas, graduated from Fairfax County’s James Madison High School in 1991 and attended Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia. High school classmate Adam Cox, 32, said his friend was always quick with a warm greeting and a grin.

“There wasn’t anyone he didn’t get along with,” Cox said. “Every time I saw him in class or walking the hallways, he was always smiling.”

Cox kept in touch with Petty during the challenging years after graduation as their close group of friends juggled work, school and adulthood. Cox recalled the buddies unwinding with cards and listening to music at parties Petty would host at his home at least once a week.

“Chris’s door was always open for me whenever I’d be there,” said Cox, who lives in Denver.

Mike Schulz, 24, of Twin Falls, Idaho, served with Petty for three months in Iraq during summer 2003. Schulz, who had just lost a child, said Petty not only comforted him, but was instrumental in helping him come home to his wife then.

Schulz said Petty was generous with the delicious treats his family often sent him. Each time a package of goodies arrived, “he made sure his troops got some of it before he did,” Schulz said. “He was always the last person to dig in.”

Also killed in the blast with Petty were Major William F. Hecker III, 37, of St. Louis; Sergeaqnt First Class Stephen J. White, 39, of Talladega, Alabama; Sergeant Johnny J. Peralez Jr., 25, of Kingsville, Texas; and Private Robbie M. Mariano, 21, of Stockton, California. They were assigned to the 3rd Battalion, 16th Field Artillery, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division based at Fort Hood, Texas.

Later yesterday, the rain held off as dozens of mourners gathered under cloudy skies for Brown’s funeral.

Brown, who was shot by a sniper in combat January 7, 2006, near Fallujah, was assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division, II Marine Expeditionary Force based at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Gaggles of geese glided above the bare trees as an honor guard from the Marine barracks at Eighth and I streets SE in the District carried Brown’s flag-draped wooden coffin forward. Gunnery Sergeant Barry L. Baker knelt before Brown’s father, Rodney Bridges, and presented the flag to him. As the ceremony concluded, a bagpiper played “Amazing Grace.”

“He loved being a Marine more than anything,” said aunt Robin Summers, 42. Despite his slender build, he had set his sights on joining the elite branch of the armed forces, she said. Ignoring naysayers, he bulked up and stayed active playing basketball and fishing — though Brown often joked that he fed more fish than he managed to catch.

As a teenager, Brown, who was known for an endearing goofiness, was determined to overcome his adolescent awkwardness. To that end, he consulted his cousin Tyler Richardson, 19, for advice on dressing to impress women. He attended his first high school dance in a tuxedo — complete with tails, a top hat and a cane. For another, he wore a gold suit.

“He was proud he had a date for each occasion,” Summers said.

During his years at Heritage High School in Newport News, Brown took his participation in the Naval Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps especially seriously, said cousin Tammy Richardson, 21, who graduated with him in 2002. “He made sure his uniform was ironed and straight,” she said. “And he made sure he graduated with good enough grades so that he could go into the military.”

Brown headed to boot camp straight out of high school and was proud to make the cut. He did two tours in Iraq and stints in Afghanistan, Japan and Korea. His aunt said one of his most rewarding experiences was returning to Heritage High in his dress blues to talk to ROTC students about the military.

He planned to go into law enforcement, she said.

Because of his service in Iraq, he was “a changed man,” Summers said. “You could look at him and tell the war had affected him tremendously.”

8 February 2006:

Kyle Brown was a skinny, gangly kid who struggled to join the U.S. Marine Corps. He died just after his 22nd birthday — a hero in Iraq.

He volunteered to return for a second tour of duty, said his mother, Theresa St. Pierre of Oak Harbor.

“He was a dedicated Marine and I am a proud Marine mother,” she said.

Kyle volunteered to return to Iraq because he thought he should be with his unit, St. Pierre said.

He was on patrol with his unit near the troubled city of Fallujah early on January 7, 2006, when they were attacked.

“Kyle took a fatal shot from a sniper’s gun. It hit him in the face and he died nine minutes later,” his mother was told by the Marine Corps.

The news was devastating to his mother and his step-father Richard St. Pierre. Although Kyle had lived mostly with his father since he was 14, family bonds remained strong.

Memories flooded back of a son who decided early on a military career. His patriotism was stirred by a great-grandfather — a World War II veteran.

But it wasn’t easy for Kyle to meet the Marines’ requirements.

As a toddler he’d suffered hearing loss due to ear infections. As a result, his speech and reading were delayed. But he was determined to graduate from high school with a full diploma. One teacher guided all his extra homework hours.

Another teacher encouraged body-building to meet the Marines’ weight requirements.

“He just didn’t scream Marines,” his mother recalled of her son’s slim physique. “He was an exceptional kid, kind and loving and it was rare for him to say a harsh word about anyone,” she said.

When Kyle was 12, he spent one summer in Europe with his maternal grandmother Anita Sherrill. Often called “Doc” because she holds two doctoral degrees, she has taught the past 10 years in Oak Harbor schools.

But in 1995, Sherrill was directing education programs for the Department of Defense in Europe.Sherill took Kyle and another grandson Jason to Disneyland Paris and then to Germany. They climbed Zitzwitz, the highest mountain peak in Germany. He was inspired. Kyle said later. “If I can climb the Zitzwitz, I can be a Marine.”

“I had a wonderful time with him,” Sherrill said.

He also meet some DARE officers from the Los Angeles Police Force who were visiting the European schools. This encounter may have led him to plan to go into law enforcement at the end of his military career.

But this was not to be.

He died along with two other Marines that tragic morning in Iraq. He was buried January 16, 2006, in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

“He died fighting for our way of life… freedom of religion… women’s rights. He saw mistreatment of women in Iraq and Afghanistan while he was there,” she said.

Kyle entered the Marines within weeks of high school graduation, completing boot camp October 2003. He trained in Korea and Japan. His first duty tour was the 2003 invasion of Iraq. He also served in Afghanistan, Africa and the Philippines.

Kyle’s mother was presented with the U.S. flag flown home with him from Iraq. She placed flowers and mementos on top of his coffin before it was lowered into the grave.

“I watched him born and I watched him laid to eternal rest,” she said.

She is compiling a book about Kyle’s life and requests anyone who knew him contact her with their remembrances. Her e-mail is [email protected].

A mememorial service is set for 2:15 p.m. on Sunday, February 12, 2006, at the Elks Lodge, 155 N.E. Ernst in Oak Harbor.

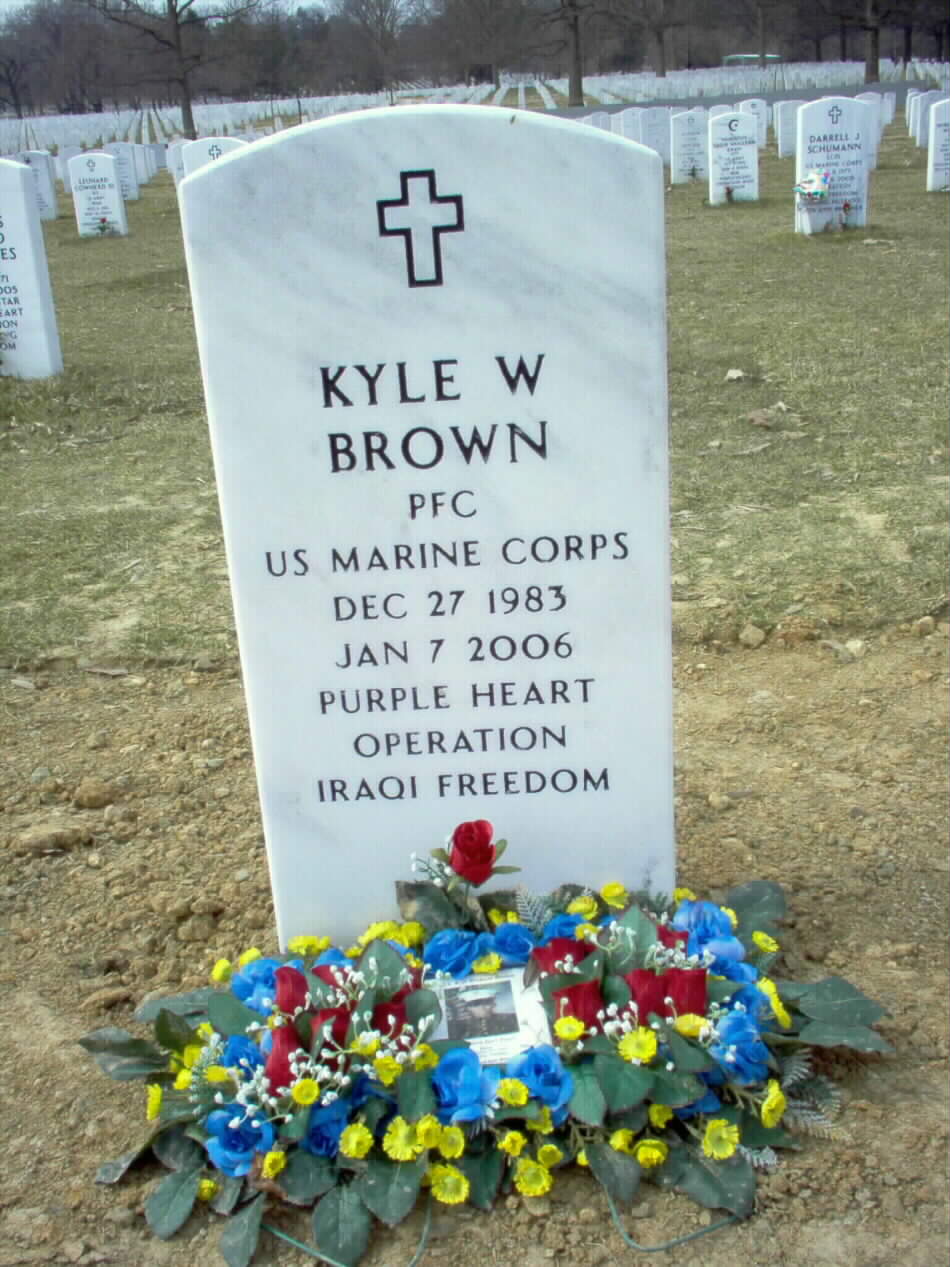

BROWN, KYLE W.

- PFC US MARINE CORPS

- DATE OF BIRTH: 12/27/1983

- DATE OF DEATH: 01/07/2006

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 8308

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard