United States Department of Defense

News Release

No. 531-04

IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 1, 2004

DoD Identifies Army Casualty

The Department of Defense announced today the death of one soldier supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom.

First Lieutenant Kenneth Michael Ballard, 26, of Mountain View, California, died May 30 in Najaf, Iraq, during a firefight with insurgents. Lieutenant Ballard was assigned to the Army’s 2nd Battalion, 37th Armored Regiment, 1st Armored Division, from Friedburg, Germany.

The incident is under investigation.

Tuesday, June 01, 2004

Mountain View soldier killed in Iraq, shortly after extended-stay order

By Nicole C. Wong

Courtesy of Mercury News

Ken Ballard, a 26-year-old tank platoon leader who spent a little more than a year in Iraq, was the kind of son “everyone should have,” his mother said. The two chatted – online or over the phone — almost every day.

“He was an only child. I was a single mom. He knew how important it was for me to hear from him,” said his mother, Karen Meredith of Mountain View.

In turn, she posted his photos from Iraq on her Web site, where the rest of the world could follow his travels and post their own messages to Ballard.

Although Ballard was in battle every day in May, Meredith said, in “one of the last e-mails he sent me, he said, `Don’t worry about us. We know what we’re doing.’ ”

On Monday morning, as the nation stepped back from its bustle to honor soldiers who died in battle, Meredith received more news about her son. He had been killed by small-arms fire in the An-Najaf area the night before. The Army had not released details about his death Monday night.

It wasn’t supposed to happen, she said between sobs, surrounded by her sister and friends in her son’s Mountain View home. There was a cease-fire. And he was scheduled to be back home by now. But an extended-stay order made him miss his May 22 welcome-home party.

Mother and son last talked Thursday — “a bonus day,” because Meredith received both a letter and a phone call from her son.

The latest update about Ballard lingered Monday evening, leaving a void in the lives of loved ones and on the Web site that Meredith created to document the daily activities of “Lt. Ken Ballard, my hero!”

It’s a personal project Meredith started last summer, when Ballard sent his first pictures home. She created the online chronicle to keep friends and family in the loop and show the world “there are real people over there.”

“It was important that people see his smiling face and for people to know what was going on in Iraq, that it wasn’t just a news story,” she said.

The photo gallery shows Ballard smiling while wearing a Santa hat. And — in his favorite picture — pointing to the fist-sized hole from the sixth rocket-propelled grenade that hit his tank.

And the comments came in, she said, from friends and neighbors, and a few complete strangers, from Antelope, California, and Cranston, Rhode Island.

A writer identified only as Uncle David wished Ballard “as happy a new year as you can have over there.” Aunt Cathy warned her nephew she was sending a batch of her rock-hard homemade cookies.

Paul Anderson, a veteran from Concord, wrote: “To be honest, it’s hard to be here riding the sofa when so many of my friends and former soldiers are serving. You are doing the right thing for the right reasons. I wish you a safe tour and a ticket home soon.”

“Some of the people who’ve posted comments on there, I don’t know, I’ve never met,” Meredith said. “He touched a lot of people’s lives.”

Ballard, born in Mountain View, joined the Army as soon as he graduated from Mountain View High in 1995. He served in Bosnia and Macedonia before taking a leave to attend Middle Tennessee State University, where he earned a degree in international relations in 2002.

“He wanted to do something to help the world,” Meredith said.

Ballard planned to serve two more years while stationed in Germany. Then, his mother said, he hoped to earn a master’s degree and work in Washington, D.C.

That was all supposed to start after his homecoming party, recently rescheduled to Labor Day weekend.

Now, Meredith said, “it’s going to be a different kind of welcome home.”

Thursday, June 10, 2004

When Army Lieuteant Ken Ballard and his tank crew rescued seven soldiers trapped in an ambush in an alley in Baghdad’s Sadr City, he had no idea one of them was his dad’s next-door neighbor in Hayward.

That neighbor, Private First Class Matt Medlock, was back in the Bay Area on Wednesday to honor his rescuer — as a pallbearer at Ballard’s funeral; the lieutenant was killed May 30, 2004, in Najaf, Iraq.

“It was the least I could do for him,” Medlock, 21, said after the funeral in Mountain View, where Ballard was raised by his mother. “After what he did for us then, I wish I could have been there for him.”

More than 300 people gathered to honor Ballard, 26, whose body was in a flag-draped coffin at the Mountain View Sports Pavilion.

On the October night when Ballard’s tank crew saved Medlock’s battered humvee convoy, the soldiers were not aware of their Bay Area connection.

The two young men bonded in combat on the other side of the world, not realizing that back on Hugh Way in Hayward, Medlock’s mother and Ballard’s father had developed a connection — sharing their fears as worried parents with sons in Iraq.

About a week after his rescue, Medlock told his mother about his close call in Sadr City. Lela Medlock, who was still upset, recounted the tale to her next-door neighbor Tom Ballard, who’s been divorced for many years from his son’s mother.

“Tom said that sounds a lot like a battle Ken just told me about,” said Lela Medlock, who raised her only child alone after his father died nine years ago. “We kind of put it together. Here I am in my front yard talking to the father of the man who saved my son’s life in Iraq.”

About a week later in Baghdad, the lieutenant walked up to the private and introduced himself as Tom Ballard’s son.

“It was a really strange scene,” said Matt Medlock. “It’s kind of unbelievable; the guy who saved our lives is my neighbor’s son.”

The two soldiers came together in a dusty alley in Sadr City about 10 p.m. on October 9, 2003. Medlock was driving the rear vehicle in a three-humvee, nine- soldier convoy patrolling the streets when his gunner spotted an Iraqi pointing an AK-47 machine gun at them.

“All of the sudden all hell broke loose with gunfire from rooftops and windows and people in the street,” Medlock recalled. “They hit us from all over with rocket launchers, grenades and gunfire.”

The attackers blocked off several streets, forcing the convoy to run a gantlet of enemy fire. As the battered convoy regrouped, Ballard appeared with two tanks. He provided security while the convoy’s soldiers tended to the wounded and tried to fix their humvees, Medlock said.

“I’m not sure we ever would have made it out of there if not for Lieutenant Ballard,” Medlock said. “Our gas tank was leaking. Our radiator was leaking. Our tires were all flat. Every type of fluid was leaking from the humvees. We were in bad shape.”

Two of the nine soldiers — Private First Class Sean Silva, 23, of Pinole and Sergeant Chris Swisher, 26, of Lincoln, Nebraska — were killed. They were in the lead vehicle and absorbed the brunt of the hostile fire.

“Lieutenant Ballard stayed there until we could get everyone out that night,” Medlock said. “From then he was attached to us and accompanied us out on patrol at night. He did a great job. I wouldn’t be alive if it wasn’t for him.”

Medlock left Iraq in April after serving a year there and is stationed at Fort Polk, Louisiana. But Ballard wasn’t so fortunate. Just before he was a scheduled to come home, his Iraq tour of duty was extended.

Ballard was killed 11 days ago in a confrontation similar to the one where he rescued Medlock. While on patrol in Najaf, a unit of tanks and humvees was ambushed. Ballard’s platoon moved straight at their attackers, allowing the other troops to safely retreat, Captain Nathaniel Durant said.

Ballard was hit by small-arms fire after rescuing everyone else.

“He took a lot of pride in keeping his men alive,” Tom Ballard said.

Ballard’s father was one of several speakers at Wednesday’s funeral who broke into tears and sobs while eulogizing him. Besides recounting his bravery, friends recounted his goofy jokes, gregarious personality, silly pranks and “mischievous Cheshire-cat grin.”

One buddy described how at Mountain View High School Ballard earned the nickname “meat” for eating a whole chicken at lunch. According to pals, he also released a baby fresh-water shark into the school’s swimming pool, doused classmates with water from an old fire extinguisher and drove the South Bay streets, leaning out a window and shouting “I’m a sexy burrito.”

There was “no secret icing on the cake, just a plain, honest man . . . who would get crazy every so often,” said Trevor Floth, a friend since childhood.

“He could listen to Metallica and Beethoven back to back and then expound at length on the merits of both,” said Lieutenant Patrick Taylor, a former college roommate. “He’s already made lots of friends in heaven.”

Ballard is the fourth generation of his family to serve in the U.S. military, said his father, who retired after 20 years in the Air Force.

Ballard enlisted after graduating from Mountain View High School in 1995 and served in Bosnia, Germany and Macedonia as a tank loader. He was offered a military scholarship to attend Middle Tennessee State University, where he received his degree in international relations.

He returned to the Army in 2002 as a tank lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion, 37th Armored Regiment of the 1st Armored Division.

In part because he started out an enlisted man, Ballard earned a reputation as a leader who always took care of his troops. That extended to other units, including Medlock’s unit, which were “adopted” by Ballard.

“I’m proud that my son saved Matt,” Tom Ballard said. “I watched both these men grow up. I’m as sad as a father can be. But I will be forever proud of my son.”

‘American Hero’ Laid to Rest

Army Soldier Who Loved His Job Is Saluted at Arlington

By Jerry Markon

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Saturday, October 23, 2004

Kenneth Michael Ballard loved being a soldier.

His father and grandfather had served in the military, and Ballard was born at an Air Force base in Upstate New York. He enlisted in the Army after high school, serving in Bosnia and Macedonia before going to Iraq.

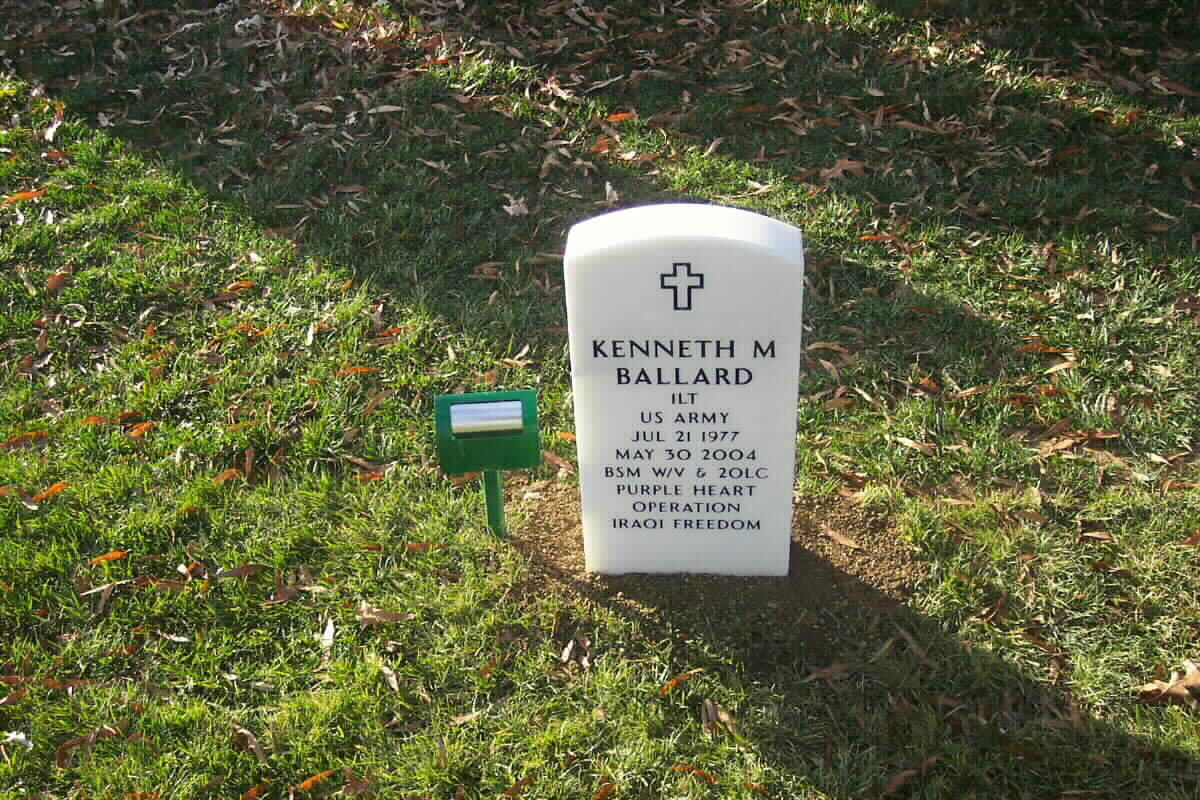

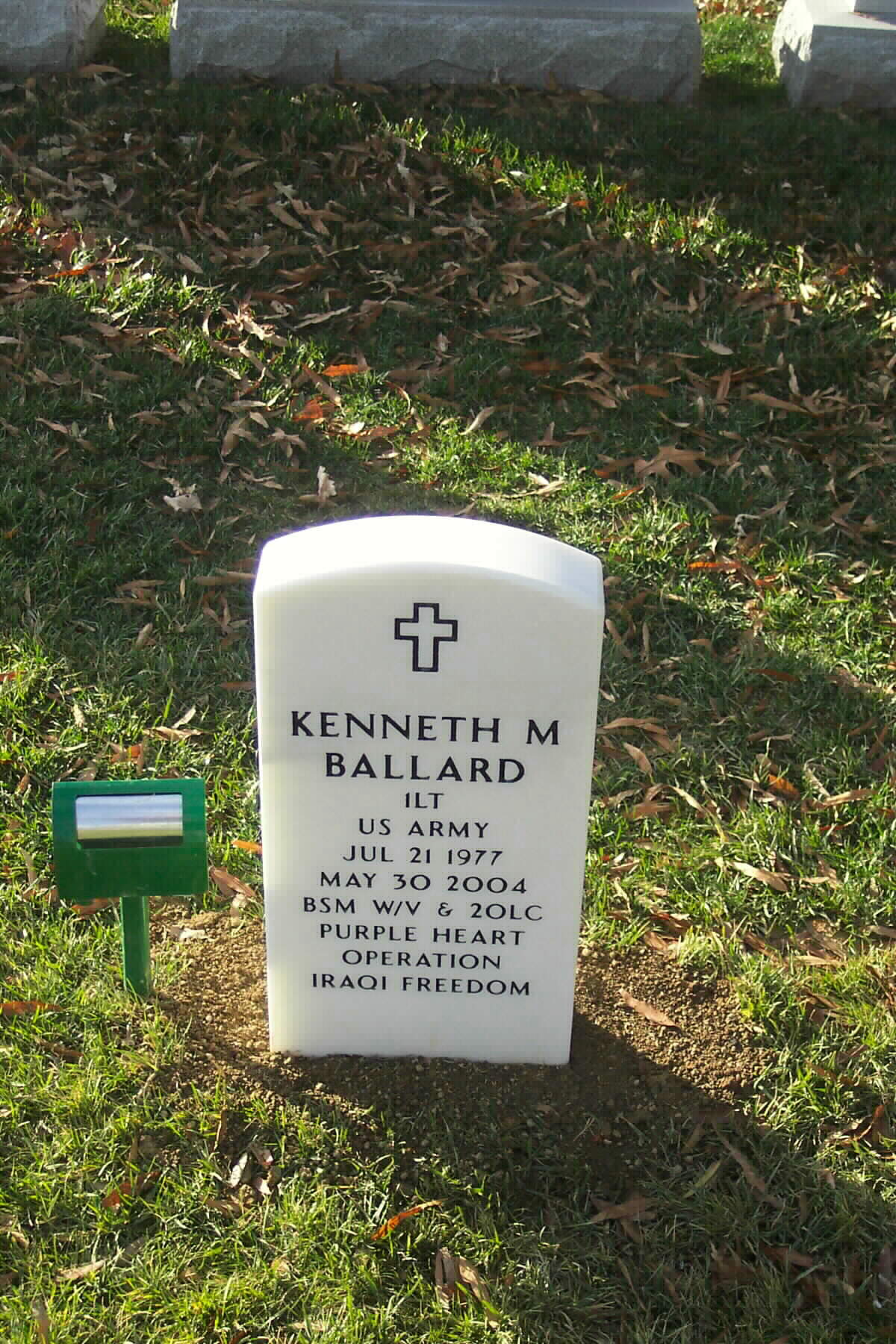

On May 30, 2004, Army First Lieutenant Ballard, 26, of Mountain View, California, died doing what he loved. He was killed in a firefight with insurgents in Najaf, Iraq. And yesterday, his remains were laid to rest in a somber ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery.

“What more can a mother ask for than for her child to be happy?” Ballard’s mother, Karen Meredith, said at a memorial service for her son in California in June. “I know you were happy being a soldier. To know that you were killed doing what you loved makes it all the more poignant. You were always my hero, and now you are an American hero.”

Meredith’s comments were posted on a Web site she maintained that featured photos from Ballard’s time in Iraq and comments from well-wishers. After he died, it became a memorial and was flooded with condolences.

Meredith did not respond to messages that Army public affairs officers said they left with her yesterday. But she was quoted by the Associated Press as saying in June that Ballard had initially been scheduled to return from Iraq eight days before he died but that his stay had been extended.

Meredith joined about 30 other family members and Army officials yesterday for a short graveside service.

After an Army firing squad saluted Ballard by firing 21 rounds and a bugler played taps, Acting Army Secretary Les Brownlee presented the soldier’s mother with the U.S. flag that accompanied his remains. He also gave her two Bronze Stars that Ballard was awarded for valor.

Ballard’s remains, which were in a brown urn, were to be buried in Section 60, next to the graves of other soldiers killed in recent action, including two whose tombstone said they had died when an aircraft was downed in Iraq in April.

Most soldiers killed in Iraq or Afghanistan and buried at Arlington have been laid to rest in the same section, said Sergeant First Class James Campbell, spokesman for the U.S. Army Military District of Washington. Ballard was the 89th soldier killed in Iraq to be buried at Arlington, Campbell said.

Ballard, whose family said he had served in Iraq for a little more than a year, had been assigned to the Germany-based 2nd Battalion, 37th Armored Regiment, 1st Armored Division. The Army had said in June that Ballard’s death was under investigation, but Army officials said yesterday they could not provide additional details.

Ballard’s death came on a day of smoldering violence in southern Iraq, during which U.S. soldiers clashed with Shiite gunmen in Najaf, shaking a tentative ceasefire with militiamen loyal to radical cleric Moqtada Sadr.

Comments posted on Ballard’s mother’s Web site by friends and family members described a fun-loving man who was very close with his family and loved serving in the military. In a speech at the memorial service in June, Ballard’s father, Thomas Ballard, praised his son’s service and sacrifice.

“After September 11, 2001, no one could have foreseen the profound effects it would have on the world, not to mention our lives today,” he said. “Ken, you will always be in our hearts and in our prayers. I love you, son, and I salute you.”

BALLARD, KENNETH M

- 1LT US ARMY

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 05/01/1999 – 05/20/2004

- DATE OF BIRTH: 07/21/1977

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/30/2004

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 10/22/2004

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 8006

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

A single red rose in hand, Karen Meredith leans over her son’s simple

white stone marker at Arlington National Cemetery.

Tears fall before words.

LINDA SPILLERS

Courtesy of Cox News Service

Karen Meredith of California stands at the gravesite of her son, 1st Lt. Kenneth Ballard, Tuesday at Arlington Natinal Cemetery.

It’s her first visit since she buried First Lieutenant Kenneth Michael Ballard, a fourth generation soldier, last fall.

Still fresh, like the soil churned behind her son’s grave for another row of dead, is her anger. Anger at the way the Pentagon refused her sole wish when her son was killed by a sniper last May to photograph his casket returning from Iraq.

Meredith wanted to capture the way fellow soldiers respectfully draped the American flag across the casket, tucking the sides just so, and the way an honor guard watched over him as he was unloaded from a cargo plane.

But the Pentagon firmly said “no.” It was against regulations and would violate the privacy of family members of other slain soldiers.

“It’s dishonorable and disrespectful to the families,” said Meredith. “They say it’s for privacy, but it’s really because they don’t want the country to see how many people are coming back in caskets.”

The Pentagon’s reasons for denying the media access to the caskets returning to Dover Air Force Base are widely reported and legally contested. What isn’t so well known is that the Pentagon refuses to allow the families of dead soldiers access to the caskets returning to Dover and other military bases.

“It’s bad enough that they won’t let the country see the pictures of the caskets, but a grieving mother?” asked Meredith. “It’s unforgiveable after what I lost.”

The Department of Defense defends its policy, which was created in 1991 by then-secretary of Defense Dick Cheney. The policy protects the privacy of families who have lost loved ones in the war and who may not want their son or daughter’s casket inadvertently photographed, said Lieutenant Colonel Barry Venable, a Defense Department spokesperson.

What families of dead soldiers really want is “the expeditious return of their remains,” not photographs at Dover, Venable said.

The department strongly discourages family members from coming to Dover to watch the caskets of the dead unload. “It’s a tarmac, not a parade ground,” Venable said. The caskets arriving at Dover are similar to the “hearse pulling up to the back of a funeral home,” he said.

Meredith says she was prepared to lose her son in battle. What she wasn’t prepared for was the way the military treated her when he died from a sniper’s bullet in the head. She doesn’t understand how a single photograph of his casket for her own personal album would violate her own privacy.

“It is ironic that this policy denies us the very freedoms of the press and speech my son — and so many like him — gave their lives to protect,” Meredith says.

Some families think the caskets should be photographed. Some families say they shouldn’t. There is no consensus on this point, said Joyce Raezer, director of government relations for the National Military Family Association, a Virginia-based nonprofit organization with 30,000 members.

The organization does not have an official opinion about requests like Meredith’s, but Raezer believes from her conversations with families who have lost a loved one that most would support allowing the family of a dead soldier to have a photograph. She suggests that the military take the photo when the casket arrives and include it in the materials they routinely give to families when there is a loss.

“There is a difference between taking photos and showing it to the world every time a plane comes to Dover and taking a photo for a personal memento for the family,” Raezer said.

Open government advocates are rallying behind Meredith and other family members who want to see photos of their loved ones at Dover. They view this as another attempt by the Bush administration to keep the actions of the government secret. They suspect that the ban is to prevent the public from getting too upset about the war in Iraq.

“I think it’s a atrocious that they won’t allow photos,” said Rick Blum, executive director of Openthegovernment.org, an umbrella organization of conservative and liberal organizations concerned about excessive secrecy in government. “The pictures show the true cost of war and the honor and the respect that the military gives to their sacrifice.”

Other open government advocates suspect that there may be political reasons for denying the public access to photograph the caskets.

“The policy keeps these remarkable images off the front pages and off television as if out of sight could mean out of mind,” said Tom Blanton, executive director of the National Security Archive, a nonpartisan research institute based in Washington. “The policy disguises this steady, mounting toll.”

The Pentagon’s policy of banning photos at Dover is being challenged in federal court by Ralph Begleiter, a journalism professor from the University of Delaware.

Begleiter has requested all still and moving images of fallen soldiers returning in caskets dating back to October 2001 when the war in Afghanistan started. He filed his request under the Freedom of Information Act, a federal law that requires agencies to make records and materials available to the public, with the support of the National Security Archive.

“This is not a partisan political issue,” said Begleiter in a release about his lawsuit posted on the Internet. “It’s all about allowing the American people to accurately and completely assess the price of war.” The case is still pending.

Venable, the Pentagon spokesperson, said there have only been two instances where the department has permitted photographs of caskets since the policy was put in place in 1991.

In 1996, Clinton personally oversaw the return of 33 caskets containing the remains from Commerce Secretary Ronald H. Brown’s plane crash in Croatia. In 2000, the Pentagon allowed photos of caskets from the al-Qaida attack on the USS Cole in 2000.

The National Security Archive keeps its own tally of examples where the images of caskets were released to the public.

The organization cites eight other examples where photos of caskets arriving at military bases were allowed, including the return of Americans killed in the 1998 al-Qaida terrorist bombing in East Africa; the caskets of six dead soldiers who died in a training accident in Kuwait in March 2001 were photographed at Ramstein Air Base; and in September 2001, the the Air Force published a photograph of the casket carrying the remains of a victim of the al-Qaida attacks on the Pentagon.

Exceptions to the rule stopped when the war in Iraq began.

10 September 2005:

The Army said Saturday it knew for more than a year after First Lieutenant Kenneth Ballard’s death in Iraq in May 2004 that he was not killed in action, as it initially reported. The family was not told the truth until Friday.

Ballard’s mother, Karen Meredith, of Mountain View, California, said in a telephone interview that she is angry and will press for a full explanation. She is a public critic of the war and has attended anti-war protests in Crawford, Texas, outside President Bush’s ranch, with grieving mother and peace activist Cindy Sheehan.

Meredith said she blames the Army’s error on official incompetence, not an intent to cover up the truth.

“This news is stunning to me,” she said. “People in the Army knew this news for 15 months, and why they couldn’t be bothered to tell me the truth when this first happened and to have me go through this pain 15 months later is unconscionable on the part of the Army. It’s a betrayal to my son’s service,” she said.

A letter from Army Secretary Francis Harvey was hand-delivered to her Friday in Mountain View. She said Harvey wrote, “I sincerely apologize to you for the unfortunate series of events that resulted in your not being informed.”

Army officials said the failure to notify the family of the true cause of Ballard’s death was an oversight. The military sometimes incorrectly categorizes the cause of war deaths. What is so unusual about the Ballard case is that the error was recognized early but not reported to the family for more than a year.

On Memorial Day in 2004, the day after Kenneth Ballard died, the Army informed his family that he had been killed by enemy fire while on a combat mission in the south-central Iraqi city of Najaf. In a casualty announcement from June 1, the Pentagon said Ballard died “during a firefight with insurgents.”

The Army disclosed on Saturday that Ballard, 26, actually died of wounds from the accidental discharge of a M240 machine gun on his tank after his platoon had returned from battling insurgents in Najaf.

He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery last October 22.

An Army spokesman, Colonel Joseph Curtin, said in an interview that separate investigations by the local commander and by the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division concluded days after Ballard’s death that it was an accident.

The tank accidentally backed into a tree and a branch hit the mounted, unmanned machine gun, causing it to fire, Curtin said. Ballard was struck at close range and died of his wounds, he added.

For reasons that are not clear, the Army did not correct the public record and inform the family until Friday.

Last spring, it was disclosed that the Army had delayed in telling the family of ex-pro football player Pat Tillman that his death in Afghanistan in April 2004 was caused by gunfire from his fellow Rangers and not enemy forces, as the Army initially reported. The Tillman case is being reviewed by the Pentagon inspector general’s office.

Curtin said the Ballard matter was a regrettable mistake and that Harvey, the Army secretary, has ordered a review of procedures in reporting accidental deaths.

“Furthermore, the Army regrets that the initial casualty report from the field was in error as well as the time that it has taken to correct the report and to inform his family,” Curtin said in a statement issued Friday night.

Ballard was a platoon leader in 2nd Battalion, 37th Armor Regiment, 1st Armored Division. During the Najaf fighting he was attached to a unit of the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment.

On May 22, approaching the one-year anniversary of her son’s death, Meredith wrote in a Web posting, “One year ago you were killed by a snipers bullet. They said you were killed instantly. There is not a minute that goes by that I do not remember answering the phone and hearing I regret to inform you.”

The 1st Armored Division, which also investigated the death, said in a written statement from its post in Wiesbaden, Germany, on Friday night that investigations had “revealed additional information of the cause” of Ballard’s death. It did not mention that the investigations were conducted more than a year ago.

21 September 2005:

A soldier’s last words: ‘Get us home’

Mother learns truth from Army about son’s death in Iraq — 15 months later

Fifteen months after her only son was killed in Iraq, Karen Meredith learned his last words, as told by his fellow soldiers.

“Hard left, hit it straight, and get us home,” Army Lieutenant Kenneth Ballard told the tank unit he was commanding in Najaf.

Then the tank driver heard a burst of machine-gun fire. Someone screamed Ballard’s name.

“I did as his last order said and got him home,” said the driver’s sworn statement, taken a day after Ballard’s death May 30, 2004.

All this time, Meredith thought her son was killed by insurgents. His unit was under attack at the time of his death.

But the report showed that although they were in combat, Ballard actually was killed in a freak accident. As the tank was moving, branches from a tree whipped a machine-gun turret toward Ballard and hit the trigger.

Because of a mixup, the report didn’t reach the proper authorities until recently.

On Friday the Army notified Meredith and her former husband, Tom Ballard of Hayward, about what really happened.

The Army met separately with both parents for several more hours Tuesday to apologize, go over even more details and answer any lingering questions.

While the revelation has shocked and upset her, Meredith said she’s now satisfied with the Army’s response.

“I am pleased to say that I feel that I have the ear of the Army as well as their heart,” she told reporters who gathered to hear her story at Cuesta Park in Mountain View. “I hope they’ll use it as a case study to help other families. The Army needs to be honest with the families.”

She wonders how many other families with questions also have been kept in the dark.

Meredith might never have learned what happened if she hadn’t been dogged in her pursuit of the truth.

Although she never suspected a coverup or foul play, she requested information in December. U.S. Rep. Anna Eshoo, D-Palo Alto, became involved and raised the request to the level of a congressional inquiry, which brought the report to light. Although the experience has painful, Meredith has no regrets.

“It doesn’t lesson his heroic service to his country,” said Meredith, wearing a button carrying her son’s picture and his dog tags around her neck.

She described her meeting Tuesday with some of the Army’s top brass as professional and sympathetic.

They told her that Ballard, 26, was posthumously awarded the Combat Action Badge.

Ballard joined the Army after graduating from Mountain View High School in 1995. He went to college on an Army scholarship and was sent to Iraq a year before his death.

Meredith said her son wouldn’t be surprised that she has become an avid anti-war activist, joining Vacaville mother Cindy Sheehan last month during her vigil outside President Bush’s ranch in Crawford, Texas.

The two of them never discussed the war much — not because it was awkward, but because she knew that he was powerless to change the situation, she said.

She said she tries to ride a delicate balance between supporting the troops while criticizing the war.

Her parents support the war, as does her ex-husband, a retired Air Force officer.

Monday morning, Meredith is flying East to join Sheehan’s “Bring Them Home Now” tour, which will march Sept. 24 on Washington.

She plans to visit Ballard’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery.

BALLARD, KENNETH M

- 1LT US ARMY

- DATE OF BIRTH: 07/21/1977

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/30/2004

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 8006

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard