Sergeant Wanted to Be With His Troops

Soldier Lost in Iraq Is Praised for Dedication to the Army, Young Platoon

In recent years, Sergeant First Class John W. Marshall, 50, talked about retiring from the Army. Each year, he would bring the papers to his wife, Denise, and ask her opinion. And each year, she would tell him the decision had to be his own.

“About the time I’d say it’s up to you, he’d be back with the . . . papers” for his retirement, Denise recalled this week.

Her husband, she said, was a soldier’s soldier who loved virtually everything about the Army.

It was cool and cloudy yesterday as John Marshall was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery. He was struck and killed by a rocket propelled grenade April 8, 2003, as he helped the 3rd Infantry Division secure a key highway intersection in Baghdad. The career Army man was the oldest member of the U.S. military to die during the war in Iraq.

For his actions in Iraq, Marshall was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart, both of which were given to his wife at yesterday’s ceremony.

Relatives said Marshall, who joined the Army shortly after high school, especially loved the consistency and discipline of military life. In the 1980s, he was forced to take a leave of more than four years while he battled Hodgkin’s lymphoma. But after beating the cancer, he rejoined the institution he loved.

“He conquered it — he went into full remission,” his wife said in an interview. “And then he went right back in.”

He spent time in Germany and Korea and served in a support unit during the Persian Gulf War in 1991, but this was his first combat, said his brother James Marshall. He told family members he could not let the young soldiers in his platoon go to war without him.

“I think he felt really committed to seeing that these young men would perform under the stress of war,” James Marshall said. “It meant giving his own life to see that they could be protected and our freedoms could be protected.”

Both of his parents were veterans, his father, Joseph, serving as an Army quartermaster during World War II. His mother, Odessa, was a medical technician with the Women’s Army Corps during the same war, one of few African American women to serve in the military at that time. She wore her Army uniform at Arlington yesterday, as Gen. Larry R. Ellis presented her with a folded American flag.

“He was an old soldier, and he was due to go home after this,” Joseph Marshall said in an interview before yesterday’s service. Major Douglas Fenton, a military chaplain who spoke at the ceremony, stressed the sacrifice of the longtime soldier.

“What a profound thing to die to protect your friends and your nation and to die to protect your neighbors,” he told the mourners.

Marshall grew up in Los Angeles but lived recently with his family in Hinesville, Georgia. He was memorialized there earlier this week; a California ceremony is planned for this weekend and will be attended by Representative Maxine Waters (D-California) and Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-California).

Although family — including Marshall’s six children, four stepchildren and eight siblings — live far away, Denise Marshall said, Marshall’s children chose an Arlington burial for their father.

“The kids were told how their dad died, and they voted,” she said. “Their dad was a hero.”

15 May 2003:

Sergeant First Class John Marshall has been buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

The 50-year-old is said to be the oldest American who died in the Iraq war. He was killed last month when he was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade during an enemy ambush in Baghdad.

Marshall’s wife accepted a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart today on her husband’s behalf.

Marshall grew up in Los Angeles and enlisted in the Army when he was 18. He was most recently based at Fort Stewart in Georgia.

Memorial services for Marshall were held last month in Baghdad and at Fort Stewart.

The Department of Defense also announced today that Sergeant First Class John W. Marshall, 50, of Los Angeles, was killed in action on April 8, 2003, in Iraq. Marshall was struck by an enemy rocket propelled grenade during an enemy ambush in Baghdad. Marshall was assigned to 3rd Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division, Ft. Stewart, Georgia.

Sergeant Marshall, the oldest casualty of Operation Iraqi Freedom, will be laid to rest with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery on 15 May 2003.

In his last dispatch before the war, 50-year-old John W. Marshall referred to himself as an old soldier with a clear purpose and little luxury to debate the reason for his mission.

“It’s really not an issue with me. I am not a politician or a policy maker, just an old soldier,” he wrote home in an e-mail. “Any doubts on my part could get someone killed.”

Marshall, based at Fort Stewart, was killed April 8, 2003, by an Iraqi rocket-propelled grenade. He is the oldest U.S. military casualty of the conflict in Iraq.

Marshall grew up in Los Angeles, enlisted when he was 18, and served stints in Korea and Germany. He and his wife, Denise, had six children, ages 9 to 17.

His mother, Odessa Mitchell, saw him in October before he headed to Kuwait, and never feared he wouldn’t come home.

“That was something my son wanted to do. He loved the Army,” she said.

The Silence Speaks Volumes at Roll Call for U.S. Infantry Unit

Courtesy of the Los Angeles Times

27 April 2003

BAGHDAD — They called the roll for the 2nd Brigade on Saturday morning.

Command Sgt. Maj. Otis Smith cried out, “Sergeant First Class Marshall,” but no answer came.

“Sergeant First Class John Marshall.”

No answer came.

“Sergeant First Class John W. Marshall.”

No answer came.

And on it went at Saddam Hussein’s parade ground. The names of seven more soldiers were called. No one answered.

That is the way the 2nd Brigade Combat Team of the U.S. Army’s 3rd Infantry Division remembered its eight men who died on the long march from Kuwait to the parade ground. Their names were spoken. Prayers were said. The brigade’s officers and men bowed their heads, and some of them wept.

The brigade chaplain, Father Patrick Ratigan, repeated the eight names and mentioned a detail from the sum of each man’s life. And after each name he repeated a single word: “sacrifice.”

The helmets of the dead men were perched on the stocks of their M-16s, their ranks still pinned to the tan cloth covers, their names still etched in ink or sewn into the thin Kevlar bands. Their boots stood in a neat row.

Everyone remarked how ironic it was, to have these men memorialized on the very ground where Hussein once reviewed his troops and, notoriously, fired a shotgun with one hand while wearing a black homburg. The parade ground was one of the first sites seized by the 2nd Brigade when it ripped through central Baghdad on the foggy morning of April 7.

Marshall, who grew up in Los Angeles, never made it to Baghdad. He was firing a Mark 19 automatic grenade launcher on an armored personnel vehicle south of the city that day when a rocket-propelled grenade, or RPG, blew his body out of the vehicle. His comrades found him several days later, buried by the enemy in a shallow grave. He died at what the military calls “Objective Curly.”

Afterward, Marshall’s commander spoke to his widow, who found comfort in the fact that her husband had died protecting fellow soldiers, said his friend, Major Denton Knapp. Marshall was a scout protecting an important ammunition and fuel resupply convoy that fought its way up Highway 8. He was 50.

The arrival of the convoy at the parade ground the evening of April 7 allowed the brigade to hold its positions overnight. Essentially, it sealed the defeat of the Republican Guard and thus the Hussein regime.

After Marshall’s name was called, the roll call proceeded: “Staff Sergeant Robert A. Stever.”

No reply came.

Stever also died on Highway 8, minutes after Marshall fell, and not far away. An RPG exploded on top of him and blew him back into his Humvee. He was 36.

Stever was not supposed to be in combat. He was a mechanic sent to repair damaged combat vehicles. But he had fired a full can of .50-caliber ammunition, reloading while speeding up the highway, before he was hit.

“Those two guys saved the convoy from being overrun by continuing to fire and exposing themselves to danger,” said their company commander, Captain Anthony Butler.

Chaplain Stephen Hommel said he was present when Marshall and Stever were hit. “They died instantly,” he said during his invocation. “It’s not a bad way to go.”

The sergeant major called out: “Corporal Henry L. Brown.”

No reply.

Brown was 22. He taught Sunday school back home in Natchez, Mississippi. He died of severe burns after a missile tore into the brigade command post south of Baghdad on April 7, just five hours after the armored convoy had pulled out for the capital. He was the brigade commander’s driver, and he died next to his Humvee.

The sergeant major called out: “Specialist George A. Mitchell.”

No reply.

Mitchell was the driver for the brigade’s operations officer. He died instantly from the blast of the missile’s 2,000-pound warhead, which hit a few yards away and spit out an enormous fireball that engulfed much of the command post compound. Seventeen soldiers were wounded.

Two reporters who were having coffee with Mitchell and phoning in their stories also died. Their names — Julio Anguita Parrado, from Spain; and Christian Liebig, a German — were read out Saturday, along with that of NBC correspondent David Bloom, who died while accompanying the unit.

The sergeant major called out: “Private Anthony S. Miller.”

Miller was a mechanic. He was standing near a group of signal company trucks when the missile struck. He died instantly. He was 19. He had joined the Army to support his mother.

The sergeant major called out: “Captain Edward Korn.”

Korn was a “friendly fire” casualty. He walked away from his vehicle during a mission southeast of Baghdad on April 3 and passed between two Iraqi tanks that had been abandoned. Fellow soldiers several hundred yards away spotted movement and mistook Korn for an Iraqi soldier.

An automatic-rifle round fired by an American enlisted man struck Korn in the torso. A 25-millimeter cannon round from a Bradley fighting vehicle, fired by an officer, ripped through him. Minutes later, an enlisted man rushed up to inform the convoy commander: “Korn is in the woods, sir.”

The sergeant major called out: “Staff Sergeant Stevon A. Booker.”

Booker was a tank commander on a “gun run” through southwest Baghdad on April 5, when a convoy of 29 tanks and 14 Bradleys stunned the Republican Guard by penetrating the city for the first time. He was struck in the head by an RPG while firing and talking on the radio, members of his unit said.

The gun run killed at least a thousand Iraqi troops, commanders said. It sent hundreds more fleeing from their positions, paving the way for the conquest of the capital beginning two days later.

The sergeant major called out: “Specialist Brandon Tobler.”

Soldiers at the memorial could not recall the date that Tobler died, but it was soon after the invasion of Iraq began March 20, in a vehicle accident somewhere in south-central Iraq. The chaplain praised Tobler as “a reservist who put his life on hold to come here and serve his country.”

The brigade commander, Colonel David Perkins, spoke of the role the eight men had played in routing Hussein’s army.

“There are actually things worth fighting and dying for,” the colonel said. “Freedom is one of them.”

The colonel sat down. A sergeant rose to read Psalm 23, and then a specialist read from the Scriptures.

Specialist Kea Brown sang “Amazing Grace,” her pure voice soaring over Hussein’s reviewing stand and above the two pairs of enormous twin sabers bookending the parade field.

Seven riflemen from Task Force 1-64, Booker’s unit, fired three volleys into the soggy morning air. A lone bugler played taps low and sweet, a tiny figure dwarfed by the tanks and the brigade’s bright flapping colors. Everyone saluted, staring straight ahead at the row of empty helmets and rifles and boots.

The sergeant major stood at attention. Roll call was over.

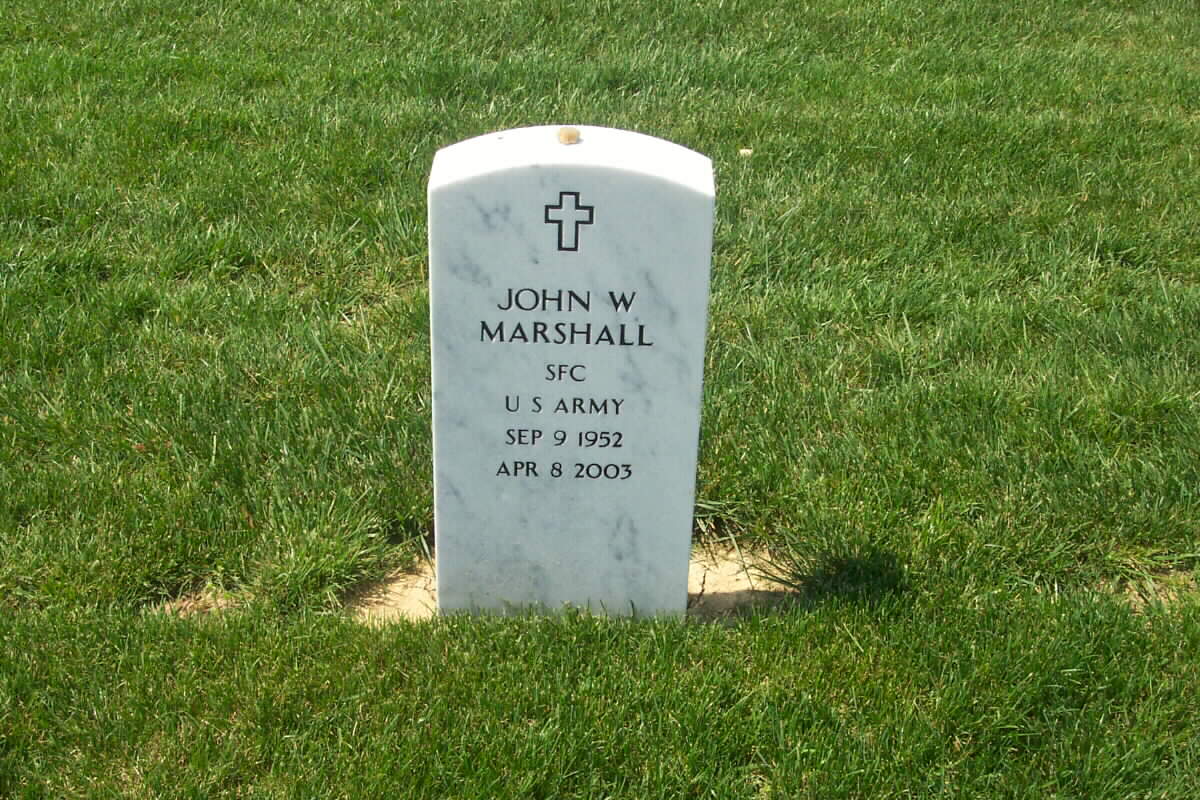

MARSHALL, JOHN W

- SFC US ARMY

- IRAQ

- DATE OF BIRTH: 09/09/1952

- DATE OF DEATH: 04/08/2003

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 7879

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard