Secretary of the Navy-Designate John T. McNaughton,

Sarah McNaughton, and Theodore McNaughton

Special Military Funeral

19-25 July 1967

Near noon on 19 July 1967, a Piedmont Airlines Boeing 727 and a private plane that was off its course collided and exploded over the Blue Ridge foothills in western North Carolina near Hendersonville, not far from the city of Asheville where the Piedmont plane had taken off only minutes before. All persons aboard both planes were killed. Among the passengers on the airliner were Secretary of the Navy-designate John T. McNaughton, his wife, Sarah, and the younger of his two sons, Theodore.

Mr. McNaughton was to have taken office as Secretary of the Navy on 1 August. At the time of his death he was Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, a post he had held since 1964. As Department of Defense officials considered formal funeral honors for Mr. McNaughton, a question arose as to his exact official status at the time of his death. As Assistant Secretary of Defense, he was entitled, under existing policies, to an Armed Forces Full Honor Funeral. As Secretary of the Navy, he was entitled to the more elaborate ceremonies of a Special Military Funeral. The decision, based on the fact that the Senate had confirmed his appointment as Secretary of the Navy, was that Mr. McNaughton was entitled to the greater honor of a Special Military Funeral.

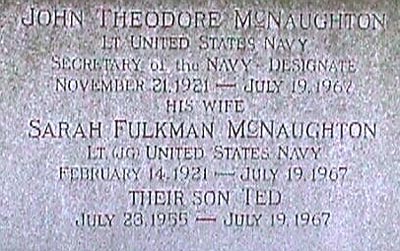

Secretary and Mrs. McNaughton were survived by their eighteen-year-old son, Alexander, their parents, and the Secretary’s two brothers and his sister. In consultations between Department of Defense officials and the next of kin, it was tentatively decided that a funeral service for Secretary McNaughton, his wife, and his son would be held in Pekin, Illinois, where the Secretary’s parents resided, and that burial would take place in Arlington National Cemetery. Mr. McNaughton was eligible for burial in a national cemetery by virtue of World War II service as a commissioned officer in the Navy. Mrs. McNaughton also had served during World War II as an ensign in the WAVES. The final decision, however, was that a funeral service for the three members of the McNaughton family would be held in Washington, D.C., at the Washington National Cathedral on 25 July, with burial in Arlington Cemetery.

The commandant of the Naval District Washington, Rear Admiral Elliott Loughlin, would automatically have become responsible for completing funeral arrangements, in accordance with the current policy that the responsibility fell to the service with which the deceased had been associated. But at the specific request of the Naval District, the Commanding General, Military District of Washington, Major General Curtis J. Herrick, accepted the responsibility for arranging and co-ordinating the ceremonies.

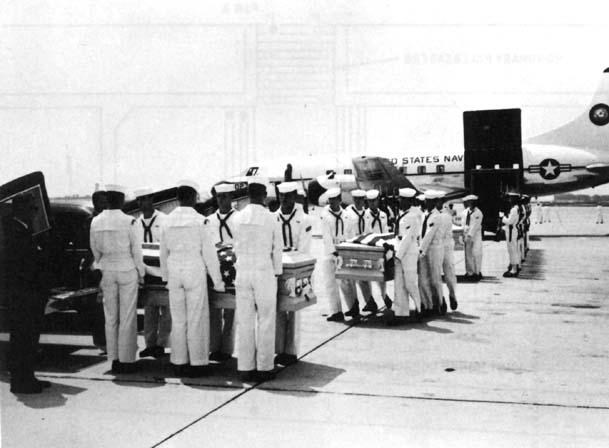

According to the plan, a Navy transport plane was to bring the bodies of Secretary and Mrs. McNaughton and their son from North Carolina to Andrews Air Force Base on 24 July. From there, the bodies were to be taken to Gawler’s funeral establishment in Washington, D.C. A joint service arrival ceremony, based on the current prescriptions for a Special Military Funeral published in 1965, was to be conducted at the airfield. But since the arrival and transfer of the bodies to the funeral home were considered primarily administrative moves, some of the usual procedures of an arrival ceremony, including the presence of a band, special honor guard, and honorary pallbearers, were to be eliminated.

The site control officer at the field was to be from the 3d Infantry. One officer and thirty-eight enlisted men of the Navy were to form a security cordon surrounding the ceremonial area, and the Navy was also to furnish three body bearer teams of six men each (plus two supernumeraries) and the petty officer in charge. A joint honor cordon, which would line the route from the parked aircraft to the three hearses from Gawler’s, was to be commanded by a Navy officer and to include eight men each from the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard. An Army color bearer and a guard each from the Marine Corps and the Air Force would make up the national color detail; the personal flag bearer would be a Navy man.

The plane bearing the bodies of Secretary McNaughton and his wife and son landed at Andrews field a few minutes after 1400 on 24 July. When the lift truck was brought up to lower the caskets from the plane, it was discovered that the platform would hold only two of the three caskets. The body bearer teams were consequently under considerable strain, being obliged to hold the first two caskets while the third was removed from the plane separately. The caskets were then carried in procession through the joint honor cordon to the hearses and taken to Gawler’s funeral establishment, where they remained until the funeral service at the Washington National Cathedral on 25 July.

The service was held at 1300. During the morning of 25 July, troops that were to support or participate in the ceremony reported to the site control officer, who was from the 3d Infantry, at the cathedral. After briefing and rehearsal, all troops were in position by 1230. A security cordon of one officer, one noncommissioned officer, and thirty-five enlisted men from the 3d Infantry took post around the north transept entrance of the cathedral to keep the ceremonial area clear. A parking and traffic control detail of five officers, eleven noncommissioned officers, and thirty-three enlisted men, also from the 3d Infantry, was on station, with a member of the cathedral police and two members of the Metropolitan Police assisting. A smaller detail of one officer, one noncommissioned officer, and five enlisted men from the 3d Infantry was on hand to control the movement of members of the press. One of the earliest to arrive at the cathedral was a detail of six men furnished by the Navy to handle all floral pieces.

An Army officer was in charge of a joint service detail of seventy-five officers and men (one officer, two noncommissioned officers, and twelve men from each service), who were to escort those attending the cathedral service to their seats. Escort officers also were present to assist and guide the honorary pallbearers during the ceremonies.

Persons invited to attend the service began to take their places in the cathedral about half an hour before the scheduled time. Members of the McNaughton family arrived at 1250, the honorary pallbearers, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey and his party, and President Lyndon B. Johnson and his party in the next ten minutes. The arrival of the family and dignitaries, all at the north transept entrance and all at approximately the same time, caused some confusion, but with the help of the site control officer, who performed as an usher himself, all were seated without undue delay.

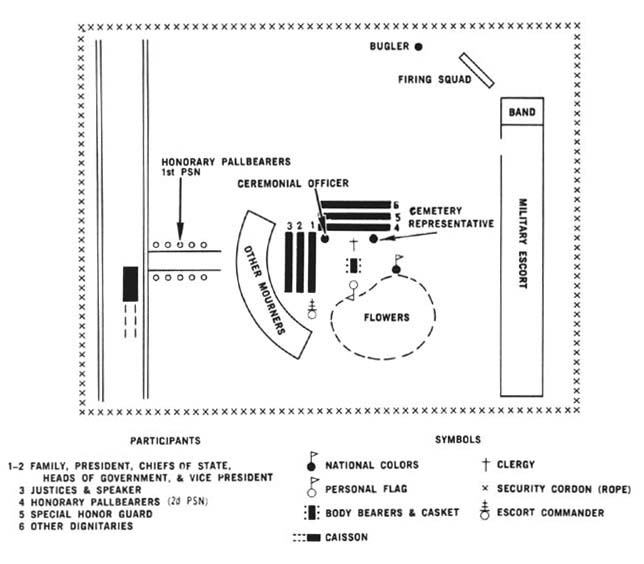

The arrival ceremony was based on procedures in the 1965 policy book, although no escort commander participated. (Diagram 103) The honorary pallbearers, among whom was Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, formed a cordon on the steps of the north transept entrance to the cathedral. A joint honor cordon of troops lined the remaining steps to the street. At the foot of the steps stood the clergy, national color detail, and personal flag bearer, and across the street, opposite the cathedral entrance, the U.S. Marine Band was in formation. Nearby were three joint service body bearer teams.

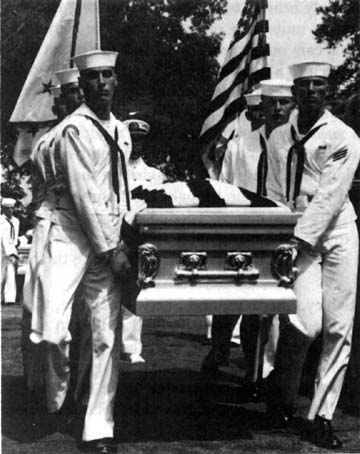

Ten minutes before the scheduled beginning of the service, hearses bearing the bodies of the three members of the McNaughton family, accompanied only by a police escort, arrived at the cathedral and halted in column along the side of the driveway leading to the north transept entrance. At the scheduled hour, they were driven to the north transept entrance and parked abreast. The US Marine Band sounded ruffles and flourishes, and as it began to play a hymn the three body bearer teams removed the three caskets from the hearses simultaneously. They were then borne in procession through the honor cordon into the cathedral, the national color detail leading, the clergy, the caskets of Secretary McNaughton, Mrs. McNaughton, and Theodore McNaughton and the personal flag bearer following. Inside the cathedral entrance the caskets, those of the Secretary and Mrs. McNaughton draped with flags, that of their son undraped, were placed on movable biers and taken forward for the service.

Mr. Adam Yarmolinsky, who had been a deputy to Mr. McNaughton during his tenure as Assistant Secretary of Defense, opened the funeral service by delivering a eulogy. Religious services were then conducted by Canon William G. Work man of the Washington National Cathedral, Dr. Joseph A. Mason of the Grace Methodist Church (the McNaughton family church) in Pekin, Illinois, and the Right Reverend Paul Moore, Jr., suffragan bishop of Washington. Two hymns were sung during the service, one of them the Navy hymn, “Eternal Father, Strong to Save.” These were led by the US Navy Band Sea Chanters. The service ended about 1345. The caskets were then taken from the cathedral in procession, and the motor cortege, without military escort, departed for Arlington National Cemetery. The departure ceremony followed established procedure, but without the participation of an escort commander or special honor guard.

According to plan, the cortege was to proceed to Memorial Gate of the cemetery. There, before a military escort drawn up on the green, the casket of Secretary McNaughton was to be transferred from the hearse to a caisson. After the transfer ceremony, the military escort was to lead the cortege into the cemetery to the gravesite in Section 5, northeast of the Custis-Lee Mansion.

In preparation for the casket transfer at the cemetery gate, all troops who were to participate in or support the ceremony were in position by 1330. The military escort included a Navy officer as commander, with a joint service staff of four, and five companies of troops, one each from the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air,Force, and Coast Guard. Each escort company had a commander, two other officers, and sixty-three enlisted men. The escort also included the US Navy Band. The entire formation was on line on the lawn at the gate, facing Memorial Drive over which the cortege would approach.

In front of and facing the escort, the caisson and caisson detail from the 3d Infantry were in the center of Memorial Drive. To the left front of the caisson a handler stood with a caparisoned horse that was to march in the cortege through the cemetery to the gravesite. To the right of the caisson stood a joint national color detail and a Navy enlisted man with the personal flag of Secretary McNaughton. Along the edge of Memorial Drive to the rear of the color bearers waited three body bearer teams, all from the Navy.

On the lawn across the street from the body bearer teams, an area cordoned by four enlisted men from the 3d Infantry had been reserved for members of the press. Other supporting troops included a 3d Infantry parking detail of one officer and four noncommissioned officers. These men were to guide the vehicles of the cortege to their positions for the casket transfer ceremony. Finally, one noncommissioned officer and twenty men from the 3d Infantry were posted as a security cordon to keep the ceremonial area clear.

Near 1430, as the cortege approached Memorial Gate, the cars were halted in a double column a short distance below the ceremonial area. Those carrying the clergy and honorary pallbearers were then signaled forward and were brought to a stop just after they turned north off Memorial Drive onto Schley Drive. The clergy and honorary pallbearers then dismounted and were guided to their positions for the transfer ceremony.

The three hearses and the cars carrying the family were next signaled forward. The hearse bearing the casket of Secretary McNaughton was halted to the right and even with the caisson; the other two hearses drew up abreast immediately behind the caisson. Immediately behind them the cars of the family were arranged in a single column. The family remained in the cars while the casket transfer ceremony took place.

After the hearses and family vehicles had been brought forward, the three body bearer teams took position. One team moved to the rear of the hearse bearing the casket of Secretary McNaughton. Those assigned to carry the other two caskets took a position flanking the hearse, three men on either side. The US Navy Band sounded ruffles and flourishes and the escort troop units presented arms. The band then played a hymn.

While the hymn was played, the body bearers transferred, Secretary McNaughton’s casket from the hearse to the caisson. After the hearse was driven away from the ceremonial area, the body bearers took positions flanking the caisson, three men on each side. The escort units then ordered arms, the clergy and honorary pallbearers returned to their cars on Schley Drive, and the escort commander and his staff moved off the green to a position on Schley Drive to lead the procession into the cemetery. Mr. John C. Metzler, cemetery superintendent, meanwhile had arrived to guide the procession to the gravesite.

Since the gravesite in Section 5 was very near the grave of President John F. Kennedy, troops from the 3d Infantry formed a cordon between the two sites to separate persons attending the McNaughton rites from those visiting the Kennedy grave. Additional troops from the 3d Infantry, who brought the number assigned to security duty to one officer and fifty-four men, cordoned a larger perimeter around the McNaughton gravesite to keep the ceremonial area clear. The 3d Infantry also supplied one officer and nineteen men to control traffic along the route of the procession to the gravesite.

As the procession marched via Schley, Sherman, and Sheridan Drives, the 3d Infantry battery, from its distant position in the cemetery, fired a 17-gun salute, spacing the rounds so that the last was fired close to the time that the procession reached the gravesite. (Diagram 108) When they were near the gravesite, the Navy Band and one platoon of each of the escort companies broke off from the formation and moved to their assigned positions at the graveside. The remainder of the escort units, not scheduled to participate in the graveside ceremony, continued to march, moving out of the ceremonial area to dismissal points.

When the cortege reached the gravesite, the caisson and two hearses were halted near a cocomat runner leading to the graves. The national color team moved to a position between the caisson and the gravesite and the honorary pallbearers, after they had left their cars, were escorted forward to form a cordon along the cocomat runner. The remainder of the funeral party assembled behind the caisson and the two hearses.

At signals from the cemetery superintendent and the site control officer, the escort units at the grave presented arms and the Navy Band sounded ruffles and flourishes. The band then began a hymn and the body bearers removed the caskets from the caisson and the hearses. The three caskets were taken in procession through the cordon of honorary pallbearers to the graves. As the procession passed, the honorary pallbearers fell in behind and were guided to their graveside position by the site control officer. The cemetery superintendent and his assistants then led the next of kin and other members of the funeral party to their positions.

At the conclusion of the graveside service, the battery delivered a second 17gun salute, firing the rounds at five-second intervals. After the last round was fired the benediction was pronounced. A firing squad then delivered three volleys and a Navy bugler sounded taps, thus concluding the final rites for John T. McNaughton, who would have been the fifty-ninth Secretary of the Navy, and for his wife and son.

The death of a family

By William Toel

Courtesy of the Pekin (Illinois) Times

15 February 2005

John T. McNaughton was a reason to be proud of Pekin — a product of our school system, graduating from high school in 1938.

In 1960 and 1961, President John F. Kennedy set out to bring the best and the brightest of America’s young talent into government service.

His words, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” in his January 1961 inauguration speech resonated across the country. Government service became the “in” thing.

President Kennedy personally recruited the Pekinite John McNaughton, then a full professor of law at Harvard.

For six years, he rose rapidly. At only 45 years of age, he had been confirmed by the Senate to begin as the Secretary of the Navy and Marines as of August 1, 1967.

His boss, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, had let it be known privately that, as his closest advisor, McNaughton could well be his choice to replace him as the next Secretary of Defense.

John was killed on July 19, 1967, in a freak plane accident. Perishing with him was his wife, Sally, and their 11-year-old son, Ted.

John and Sally had gone to Asheville, North Carolina (population 67,000) to pick up Ted after summer camp in neighboring Hendersonville (population 7,000). They were going home to celebrate his 12th birthday that coming Sunday. Their other son, 18-year-old Alex, was arriving in Europe for a post high-school trip.

Two minutes and 37 seconds after a routine take off, in a gentle climbing left turn, a small red plane came “out of nowhere” to hit the Boeing 727 in which the McNaughtons were flying. The impact was on the left lower fuselage of the 727, just behind the cockpit, and the wing of the Cessna 310 sliced upward to exit above the food galley on the right side.

The momentum of the 727 took it on a bit further; it then flopped over and fell from the sky.

Bodies fell out “like confetti,” one witness said, scattered over a mile of ground. One went through the roof of a house and landed in the living room, a child landed next to a man pumping gas, and a stewardess fell on the median strip of a busy four-lane highway. Some of the bodies landed in the summer camp area from which John and Sally had just picked up Ted.

The picture of the McNaughtons, taken an hour or so before boarding, is here to see. At noon, 12:01:08 to be exact, they were gone … along with 81 others; 81 important stories.

There were no survivors.

No one will ever know how such a freak accident could have happened. The combination of actions that day, described as a tragic comedy of errors, caused the two planes to collide at a spot where neither was supposed to be.

In the small plane was a pilot who was a pro; a perfectionist with more than 10,000 hours in the air; a World War II vet who “taught our boys how to fly.” Yet that day, he was strangely a bit off course.

An air traffic controller, in a rare slip up, failed to make it clear which of four charts to use to approach the airport, thus directing the Cessna over a ground marker that didn’t exist on the map.

A veteran airline captain and crew, proudly flying their company’s very first jet, reveal a bit of impatience in their cockpit chatter. They are 20 minutes behind schedule. They decide to leave the takeoff path just a bit earlier than directed, to make a left turn to get their plane heading toward their next destination.

The employees of the Asheville tower and hundreds of others, including workers at a G.E. plant on lunch break on a pretty 74-degree day, watched the 727 climb that day. A big jet was still unusual for a small airport.

Then at 6,132 feet they watched it die.

The National Guard, the FBI, the FAA, the NTSB, and an endless stream of lawyers and investigators combed through the evidence. After 37 years we’ll never know the how. All had to be just a bit out of kilter, a bit too weird, to get this to happen in a fatal way.

One thing we do know, without a doubt: John had been changing minds at the White House and all over Washington, D.C. Like his hero, Adlai Stevenson, he was a man of genuine compassion: Peace and the dignity of human beings was very near his heart.

Sally was a lovely person who loved to laugh, a classy wife and mother; Ted, an ultra-bright boy full of joy, who never got to his party … or to live a full life.

The McNaughtons were a class act. A Pekin family from 1925 to 1981: They were people a lot of Pekinites went to school with, rubbed elbows with. Here in Pekin they had their guts ripped out on that July day.

John’s father, known as F.F. or “Mac,” owned our newspaper in Pekin. After John’s death, F.F. was never the same again.

The voice of our town was reflected in his down-to-earth columns. (The ghost of the Ku Klux Klan — very alive before — was mostly exorcised from Pekin with his simple and fearless words.) That voice lost its zest.

A nation suffered, too. Without John’s support, counsel and friendship, Secretary of Defense McNamara was moved aside.

The Vietnam War John had helped restrain now escalated rapidly. After John died another 40,000 American boys were killed, 120,000 chopped up and maimed, and about 1 million came back damaged emotionally and mentally.

In the vacuum John left behind, one of his employees copied pages John had held tightly under his wing.

The employee handed the papers over to the New York Times, and brought down a president and his government in a mess called Watergate.

President Johnson, Vice-President Humphrey, Senate leader Dirksen (another pure Pekin product) and everyone who was anyone, came to the National Cathedral and Arlington National Cemetery.

In nearly 100 black limousines and staff cars, they came to lay these three Americans to rest; both Sally and John with full military honors. The riderless black horse with boots backward, the muffled drums, the horse-drawn caisson with flag-draped coffins and hundreds of service people in crisp uniforms: All that the nation experienced with John Kennedy’s funeral less than four years before was replicated for another American patriot on July 26, 1967.

These McNaughtons rest in peace only a few feet from the Kennedys. The story of John has a good ending, though.

John’s dad opened a letter from him about an hour before the crash. The letter ended, “All’s well, John.”

We don’t need Christmastime movies to remind us that our lives inadvertently touch, and make richer, many others.

In World War II, when the ship’s captain and most of the crew of an important munitions vessel abandoned ship after an attack, a young U.S. Navy lieutenant, John McNaughton, brought it to port safely. He was decorated for bravery.

Sally also volunteered and served as a WAVE lieutenant in World War II. When people in Pekin had need, quietly John was generous.

While in Washington D.C., John worked tirelessly and traveled the world working on peace, disarmament, and innovative ways to solve problems.

In thousands of little ways, with people in Pekin, and around the world, “All’s well” is the good word because John lived.

The McNaughtons aren’t here anymore.

F.F. sold the paper and died in Arizona in 1981. The family scattered mostly toward the coasts. But this bright tough Scottish stock left its mark on Pekin.

A generally good-looking people, they had money, but like John’s buddies here in Pekin said, “You’d never know it.”

These were Pekin kind of people, drawn to this place, our work ethic, our mentality.

In Pekin, you get respect by working hard and speaking straight. F. F. was often at the paper by 5 a.m., then went home to have breakfast before a full day of work.

John worked hard, too. That’s how you get to DePauw University, Harvard Law School and Oxford University. That’s how you get recognized as a Rhodes Scholar — and that is what President John F. Kennedy saw.

Young McNaughton was bright, but there are lots of bright people in the world. This young man had the best of Pekin written all over him. He knew how to work and was a straight shooter.

He spoke the truth, even when it put him on the opposite side of much of the military brass and the majority of his own government.

In the long run John was right on. John and Sally, Ted and Alex, and the whole clan added a solid layer to our overall collective personality. They did — and they do — make us proud to be from Pekin.

Footnote

John shared with the rest of us in Pekin a lifetime disdain for the trappings of formality and the kind of people who thought they were above others. He laughed often and could make others laugh.

John was not ashamed of his small town Midwestern roots: He spoke of it with pride. He could — and did — switch into his Pekin accent to poke a bit of fun at those who got a little full of themselves. (In Pekin we think everyone else has an accent: They get a kick out of ours).

Epilogue

In the desire to “do something” for John T. McNaughton, we rushed through a bridge in his name. By Sept. 8 — barely six weeks after his funeral — $2,050,000 was appropriated for the feasibility study, acquisition of land and right of way, core drillings, and immediate construction of this monument.

Gov. Otto Kerner, with near unanimous support, made things happen. The old Pekin Bridge, of great character, was torn down and the McNaughton Bridge of today appeared.

Sadly — with the best intentions — we built a monument as cold, characterless and purely traffic-efficient as John was warm and full of life, with a great human heart of compassion.

As a kid, John walked across the old Pekin Bridge, intimate with the sights, sounds and smells of the river flowing right below his feet. (Pekin has always been a river town … not a farm town.)

From his “monument” you’d never know there was a river below.

So that we remember correctly, we publish here, exactly as it appeared on July 20, 1967, John’s mother’s (Ceil) and father’s column, written only hours after he, Sally and Ted died. Let this great and gutsy piece of writing better reflect John’s memory.

William Toel, Pekin Illinois

From a contemporary news report:

“Hendersonville, North Carolina, July 19, 1967: Eighty-two persons, including Secretary-Designate of the Navy John T. McNaughton, were killed today when a jetliner collided with a smaller plane and spiraled to earth.

The jetliner was Piedmont Airlines flight 22, a Boeing 727, bound from Atlanta to Washington, D.C. with 74 passengers and a crew of 6. Three other persons died aboard the smaller craft, a twin-engine Cessna owned by Lanseair, Inc., a Springfield, Missouri, company dealing with aviation insurance.

Accompanying the newly appointed Navy Secretary on the flight were his wife, Sally, and their son,Theodore, 11. They were returning from a trip to Weaversville, North Carolina, where the boy had attended summer camp.

The collission occured at 12:01 PM, 2 minutes after the Piedmont flight departed from Asheville-Hendersonville Airport. It has one more scheduled stop, at Roanoke, before continuing on to Washington.

Piedmont first announced that the jet carried 73 passengers, but tonight a recheck of the boarding lists indicated a total of 74. The Associated Press reported that the private plane was off course. Harold Roberts, chief of the FAA tower at Asheville Airport, said the Cessena “was about 12 miles south of where it should have been.” An eyewitness said that the small plane ripped into the climbing jet’s fuselage back of the left wing. “The jet started to nose downward and I could see bodies falling out of the fuselage like confetti,” he said.

McNaughton was born on November 21, 1921 and had served as a Lieutenant in the Navy during World War II.

He, his wife and his son are buried in the same site in Section 5 of Arlington National Cemetery.

Sarah Elizabeth Fulkman McNaughton

Theodore McNaughton

MCNAUGHTON JOHN THEODORE

- LT U.S.N.R.

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF BIRTH: 11/21/1921

- DATE OF DEATH: 07/19/1967

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 07/25/1967

- BURIED AT: SECTION 5 SITE 7004-B

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

MCNAUGHTON, THEODORE MINOR SON OF JOHN THEODORE

- DATE OF DEATH: 07/19/1967

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 07/25/1967

- BURIED AT: SECTION 5 SITE 7004-B

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard