Name: Heinz Ahlmeyer, Jr.

Rank/Branch: O1/USMC

Unit: H & S Co., 3rd Recon BN, 3rd Marine Division, Khe Sanh, South Vietnam

Date of Birth: 06 February 1944

Home City of Record: Pearl River NY

Date of Loss: 10 May 1967

Country of Loss: South Vietnam

Loss Coordinates: 163706N 1064404E (XD845485)

Status (in 1973): Killed in Action, Body Not Recovered

Category: 2

Acft/Vehicle/Ground: Ground

Refno: 0678

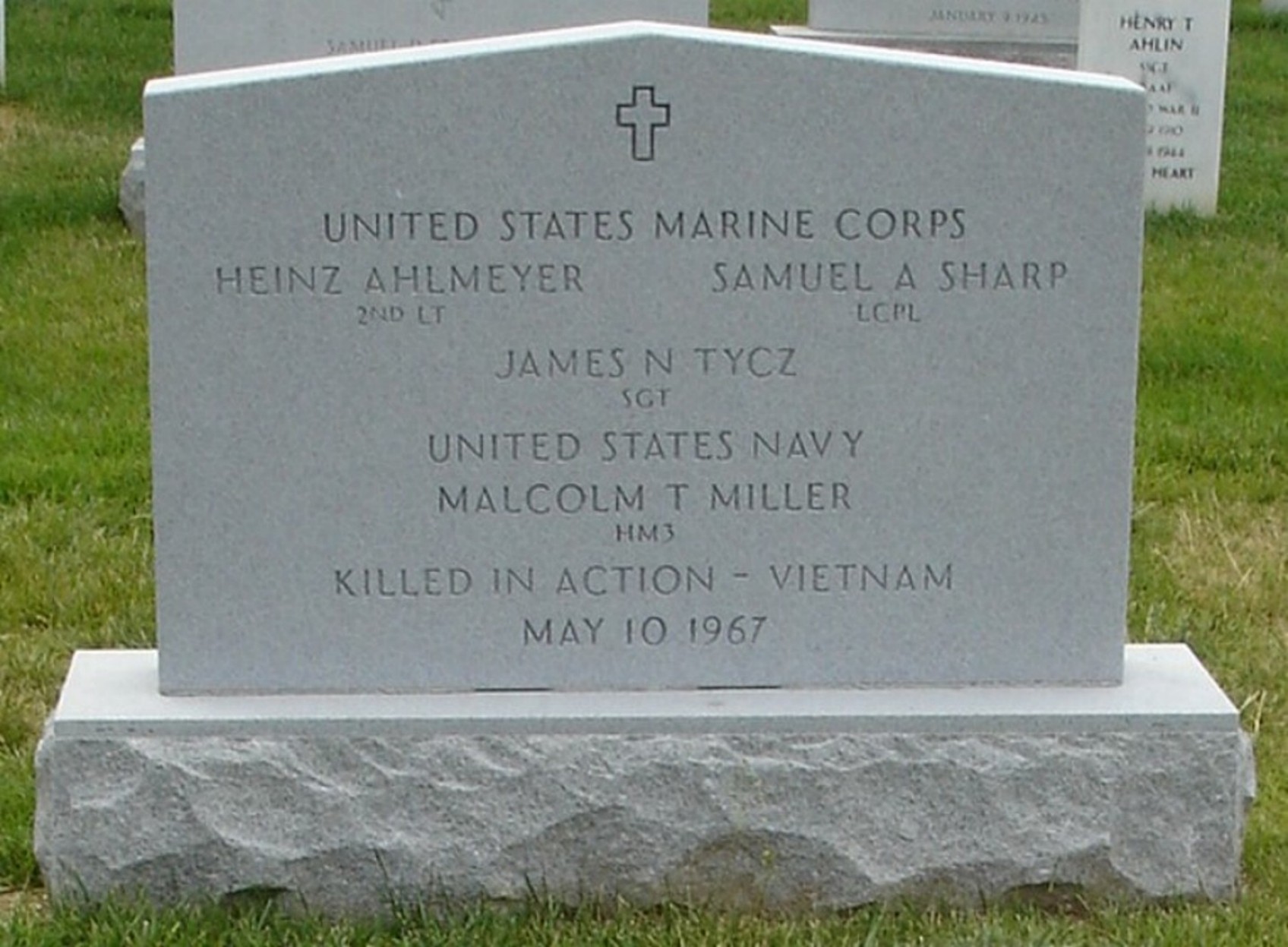

Other Personnel in Incident: Malcolm T. Miller; James N. Tycz; Samuel A. Sharp

(all missing)

Source: Compiled by Homecoming II Project 01 April 1990 from one or more of

the following: raw data from U.S. Government agency sources, correspondence

with POW/MIA families, published sources, interviews. Updated by the P.O.W.

NETWORK.

SYNOPSIS:

Third Class Petty Officer Malcolm T. Miller was a Hospital Corpsman assigned to H & S Company at Khe Sanh, South Vietnam. He was working with A Company, 3rd Marine Reconnaissance Battalion, 3rd Marine Division at Khe Sanh on May 9, 1967.

On that day, Miller joined a reconnaissance patrol from A Company that had the mission of gathering intelligence information on suspected enemy infiltration routes near their base. The patrol was helicopter lifted into an area just south of the DMZ, where they found signs of recent enemy activity, and moved to high ground to establish a night defensive position.

Shortly after 12 p.m. the patrol came under heavy small arms fire, and several of the team were wounded. Twelve hours later, after numerous unsuccessful attempts, a helicopter was finally able to land and retrieve the wounded. It was not possible to retrieve the bodies of those who had died, including Miller, LCpl. Samuel A. Sharp, Jr., Sgt. James N. Tycz, and 2Lt. Heinz Ahlmeyer, Jr. All were said to have died during the action from wounds received from enemy small arms fire and and grenades.

The four men left behind near the DMZ were never found. The government of Vietnam has been consistently uncooperative in releasing remains they hold or in allowing access to known loss sites.

Even more tragically, evidence mounts that many Americans are still alive in Southeast Asia, still prisoners from a war many have long forgotten. It is a matter of pride in the armed forces, and especially in the Marines Corps, that one’s comrades are never left behind. Many men have been killed trying to bring in a wounded or killed buddy. One can imagine the men missing from A Company, as well as Malcolm Miller, had they survived, being willing to go on one more patrol for those heroes we left behind.

Marine who died a hero heads home

After 38 years, remains of sergeant killed in Vietnam positively ID’d

Thursday, February 24, 2005

By PAUL MEYER

Courtesy of The Dallas Morning News

PLANO, Texas – James Neil Tycz died a hero May 10, 1967, when a hand grenade exploded near his face in Khe Sanh, Vietnam.

Of his seven-member reconnaissance patrol team, only three Marines survived the early-morning firefight with the North Vietnamese army, according to military records. The others were buried under elephant grass on Hill 665, unrecovered but not forgotten.

On Wednesday, over a kitchen table in Plano, Sergeant Tycz’s family heard the news they’ve waited 38 years for: The sergeant’s remains – three teeth – had been located in Vietnam and positively identified. He was coming home.

“It was a mixed blessing for me,” said Phillip Dale Tycz, Sergeant Tycz’s brother who lives in Plano with his wife, Ruth.

“I was happy they could find the remains so he could finally be repatriated. But I also knew some of my family would have a very mixed reaction. They put it behind them and didn’t want to know anything else.”

Mr. Tycz, heading family efforts to keep abreast of the search for their relative in recent years, was first notified of the discovery January 10 by telephone. Hattie Johnson, head of the U.S. Marine Corps’ POW/MIA Affairs office, flew in from Quantico, Va., to brief the family on details of the discovery.

The search

The search for the four Marines buried on Hill 665 is a story of science, detective work and perseverance that began in 1991, when two Vietnamese entered a U.S. POW/MIA office in Hanoi saying they had access to the remains of 10 U.S. servicemen, including Sergeant Tycz, according to military records.

The two men never substantiated their claims, but a month later another Vietnamese made a similar assertion in Hanoi. He produced three teeth, one bone fragment and identification for Sergeant Tycz but left after being told of military policy not to pay for remains.

From 1993 to 1998, teams worked in Vietnam on six occasions in search of the men.

They found circumstantial evidence, evidence of a firefight, but no burial.

A break came in 2003 when a team returned to the hill and recovered several fragments of teeth and bone. Last year, an excavation of the site near the border of Vietnam and Laos was completed.

In all, 31 teeth and tooth fragments were found and used in a Hawaii laboratory to identify the four Marines.

Military officials met recently in Tennessee, Georgia and Washington state with the families of the three other Marines.

“So many people don’t realize what the government does for these men and women,” Mr. Tycz said Wednesday.

“They don’t give up on them.”

More than 1,800 Americans from the Vietnam era are still unaccounted for in Southeast Asia, according to the most recent statistics. Of those, about 970 are still being actively pursued.

Navy Cross

Sergeant Tycz was 22 when he died. He was awarded the Navy Cross, the Navy’s second-highest medal, for his actions on Hill 665.

A live grenade had landed near a wounded Marine. The sergeant moved toward it, picked it up and attempted to throw it back at the enemy.

The grenade exploded after a short distance and Sergeant Tycz fell, critically wounded.

In the coming weeks, his three teeth will be flown in from Hawaii and placed in a container inside a flag-draped silver metal casket. A full uniform will rest alongside it.

Sergeant Tycz’s remains will be buried in Arlington National Cemetery, per his family’s wishes.

“He will be under full military escort, just like it happened yesterday,” said Timothy Nicholson, assistant program director for Navy Mortuary Affairs.

In addition to his brother in Plano, Sergeant Tycz is survived by another brother, Peter Carey Tycz of Milwaukee; and two sisters, Rita Blount of Escondido, California, and Patricia Kriesher of Downey, California.

Just a day after he died, Sergeant Tycz’s mother received a letter from him. In it, he wrote:

“I had an interruption just now. Our lieutenant passed me the word that we go in at 7:30 a.m. tomorrow. None of us want to go, but that’s our job and I pray I will never fail to do it. …”

Posted on Mon, Mar. 21, 2005

Burial scheduled at Arlington for soldier killed in Vietnam

MILWAUKEE – The four siblings of a Milwaukee Marine killed in Vietnam 38 years ago when he picked up an enemy grenade to save the lives of his men will gather May 10 at Arlington National Cemetery for a burial with military honors on the anniversary of his death.

James Neil Tycz’s remains had been left at the scene near Khe Sanh when the survivors were evacuated on a helicopter, and he was listed as “Killed in Action-Body Not Recovered” until American military casualty teams returned to the spot decades later.

“I’m glad it’s over,” said Peter Carey Tycz of Franklin, who was four years younger than his brother and joined the Marines because of him.

James Neil Tycz, who served in Company A in the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion of the 3rd Marine Division, was awarded the Navy Cross for the incident. The award is one notch below the Medal of Honor.

He was leading a patrol in enemy-controlled mountainous territory, when he and his men were detected by a North Vietnamese Army unit of as many as 50 men, according to the Navy Cross citation.

When a grenade landed near a wounded Marine, Tycz ran toward it, picked it up and threw it. But the grenade traveled only a short distance before exploding, killing Tycz.

His siblings were notified last month that three teeth that were later recovered from the site were from their brother.

Monday, March 28, 2005

Marine killed in 1967 finally coming home

BY MEG JONES

Courtesy of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Sigmund and Agnes Tycz never had a chance to bury their son – their 22-year-old Marine named James Neil Tycz.

He died on the hilltop overrun with elephant grass on a hot and humid day in 1967. When the three survivors of a seven-man Marine reconnaissance team were finally airlifted to safety off Hill 665 near Khe Sanh, they looked down from the helicopter to see the bodies of Sergeant Tycz and his three fallen comrades.

Listed as “Killed in Action-Body Not Recovered,” Tycz remained on Hill 665 until American military casualty teams returned to the spot decades later.

His brother, Phillip Dale Tycz, 61, gave the military a sample of his DNA in the hopes one day his brother’s remains would be identified. It wasn’t needed. All that was found of Tycz were three teeth, which were identified through dental records.

Now Tycz’s remains will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery. His four remaining siblings – his parents died within two months of each other in 1988 – will gather at the cemetery on May 10, the anniversary of his death, to finally lay their brother to rest.

“I’m glad it’s over,” said Peter Carey Tycz, who was four years younger than his brother and joined the Marines because of him.

Phillip Dale Tycz was working at Mobil Oil in Milwaukee the day his family found out his brother had died in Vietnam. One of his sisters called to tell him the horrible news.

“It was heartbreaking. It still hurts when I think about it now,” Phillip Dale Tycz said recently from his home in Plano, Texas. “I felt sorry for Mom and Dad. Dad really took it a lot worse than I expected.”

A TRANSFER AND A PROMOTION

Sigmund and Agnes Tycz received a letter from their son on May 9, 1967. In the letter, Tycz told “Mom and Pop” that he had been transferred to a new platoon and promoted to Platoon Sergeant.

“The change is a little strange, of course, but I know once my men and myself get used to each other, everything will be just great. They’re a platoon of good Marines and I plan on keeping them that way, with my newly acquired `Sarge’s growwwl!’ (Would you believe_my squeak??!)”

He mentions the fighting around Khe Sanh, sand-bagging his living quarters because of nightly mortar attacks and the sad task of being a stretcher bearer for wounded and dead soldiers and Marines.

“None of us here like this war, especially after seeing a friend or a fellow Marine wounded or worse, but the majority (I hope for the sake of democracy) believe in fighting off Communist aggression in a weakened country … Our lieutenant passed me the word that we go in at 7:30 a.m. tomorrow. None of us want to go, but that’s our job and I pray I will never fail to do it.”

The letter was signed “Your Marine Son, Neil” and below his signature was a sketch of an American flag and the note: “The U.S. is `in.’ It is free!”

HONORED FOR BRAVERY

He was killed one day after his folks received the letter. Tycz, who served in Company A in the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion of the 3rd Marine Division, was awarded the Navy Cross for his extraordinary bravery. The award is one notch below the Medal of Honor.

Leading a seven-man recon team on a patrol in enemy-controlled mountainous territory, Tycz and his men were detected by a North Vietnamese Army unit of as many as 50 men, according to the Navy Cross citation.

Tycz’s team was attacked by small arms fire and mortars, and within minutes, one Marine was killed and three seriously wounded – but not before they killed several enemy soldiers.

Tycz deployed the rest of his men, moved among them to direct their fire and shouted encouragement. When the radio operator was hit, Tycz used the radio to call in artillery fire on enemy positions, and when a grenade landed near one of the wounded Marines, Tycz ran toward it, picked it up and threw it. But the grenade traveled only a short distance before exploding, killing Tycz.

Since the area where Tycz and the three other Marines died was in enemy territory, the military had to leave their bodies behind. From 1993 to 2004, U.S. Marine Casualty Department members visited the isolated site of the firefight eight times, a place that local tribesmen stayed away from because they considered the hilltop haunted.

The first evidence was discovered in 1998 — remnants of American uniforms, 31 teeth, nine of which were identifiable, and bone fragments that couldn’t be identified. Last month, Tycz’s siblings were notified that three of the teeth were from their brother.

Now as they prepare to travel to Washington, D.C., for his burial, his family remembers the brother who earned a letter on the high school tennis team, who totaled his older brother’s 1958 Pontiac Bonneville on the day he got his driver’s license, who joined the Marines because he wanted to do something with his life, who gave up a cushy assignment as a general’s aide to go to battle, who wanted to serve his country.

Marine Sergeant James Neil Tycz and three other U.S. servicemen were killed on Hill 665 near Khe Sanh, Vietnam on May 9, 1967, close to the Laos border, in a battle with North Vietnamese troops. It was too dangerous to recover their bodies, so for decades, they were listed as “killed in action-body not recovered.”

But this year, the military informed the families that it had finally identified the remains. On Tuesday, the 38th anniversary of their deaths, three of the men will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery. A fourth man was buried last month, but will be honored at the ceremony.

Tycz, who died at 22, was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for extraordinary heroism, led a seven-man reconnaissance team into enemy territory, where members came under fire from a North Vietnamese Army unit of between 30 men and 50 men.

Tycz was just 5 feet 9 inches tall and 125 pounds when he joined the military, recalled his older brother, Phillip Dale Tycz.

“He had a high voice,” said Tycz, who now lives in Plano, Texas. “It was hard for us at home to picture him as a sergeant. In movies, these are big guys. He wasn’t a take-charge-type kid. He was very humble.”

The Navy Cross citation says that when a hand grenade landed near one of the seriously wounded Marines, Tycz “courageously and with complete disregard for his own personal safety moved forward, picked up the grenade and attempted to throw it back at the enemy.” But the grenade exploded after going just a short distance, critically wounding Tycz.

For several years after his family got word of his death, relatives held out hope he might still be alive because no body had been recovered.

“When the troops were coming back, and it was on TV all the time, there was a lump in your heart that maybe you’d see him,” Tycz’s brother said.

The family of another serviceman from that group, 20-year-old Navy corpsman Malcolm Miller of Tampa, Fla., went through a similar emotional journey.

“We held out hope for a long time,” said Miller’s older sister, Sandy Keheley of Madison, Ga. “My father kept writing letters trying to get confirmation. In the ’80s, we finally decided it had really happened. We had to accept it.”

In Miller’s last letter to the family, he complained, “Don’t y’all love me anymore? I haven’t received any mail from any of you.” The family had been writing, Keheley said, but Miller was in the backcountry, where mail had not gotten through.

The sister of another missing serviceman, Marine Second Lieutenant Heinz Ahlmeyer Jr., was stunned when the military informed her that it had identified his remains.

“I did not expect them ever at this point to find it,” said Irene Healea, who lives in Watertown, Tenn. “If he had been killed, and the body hadn’t been recovered, we’re looking at a place where there are scavenger animals. Would you really expect them to find what was left?”

Ahlmeyer, who was 23 when he died, grew up in Pearl River, New York, about 30 miles north of New York City, and played soccer at the State University at New Paltz. An award in his name is given annually at the school.

The fourth serviceman, Marine Lance Corporal Samuel Sharp Jr., of San Jose, California, was buried in his hometown last month.

“It’s been hard, like there’s still something missing,” said a sister, Janet Caldera, of Spokane, Wash. “Until you have him come back, you still wonder if he was really killed. You have that question in the back of your head. We never thought we’d have the remains come back. It’s kind of a miracle to us.”

Caldera recalls getting a note during English class in 1967 telling her to report to the principal’s office, and then being sent home. As she turned the corner, she saw a Marine vehicle in front of the house.

“My dad collapsed when he heard the remains weren’t coming home,” Caldera said. “I think that was the hardest part, that he wouldn’t be coming home.”

10 May 2005:Four decades to the day after Malcolm Thomas Miller, a redheaded Navy petty officer from Tampa, perished on a blood- stained hill in a hellish corner of Vietnam, a military honor guard on Monday welcomed Miller and two comrades to hallowed earth at Arlington National Cemetery.

Their homecoming with full military honors ended a long forensic mystery and brought closure to three families and several veterans who last saw Miller firing his weapon and being hit by a grenade.

Some 300 people attended the ceremony, including grown relatives who had never seen the three men who died before they were born. Legendary General P.X. Kelley, onetime commandant of the Marine Corps, gave family members folded flags that had accompanied the remains from Vietnam via Hawaii.

Parts of the men were buried in four bright silver caskets, which glinted in the sun as ceremonial shots were fired and a bugler played taps. In each casket were teeth positively identified as belonging to each man. In the fourth were other teeth and bones probably belonging to the men but not conclusively identified.

“Although it has been nearly 40 years, the value of their sacrifice has not been diminished,” said Miller’s military clergyman, Navy Lieutenant Commander Robert Rearick.

Tom Sherlock, the cemetery’s historian, said the “repatriation” ceremony eclipsed all but perhaps a few. “This is the biggest group I’ve ever seen,” remarked Larry Greer, spokesman for the Defense Department’s Prisoner of War and Missing Personnel Office.

They included dozens of Vietnam veterans, members of Rolling Thunder, who zoomed in on glistening black motorcycles to present plaques marking the recovery of the bodies to the families. One by one, they also stepped up to each coffin, laid beads across the top as a tribute, and saluted.

Then a Native American member of the group sprinkled dust from a leather pouch and spread incense. In the crowd, grown men who remembered the battle brushed back tears and members of Rolling Thunder comforted the families with handshakes and hugs.

Wednesday, May 11, 2005

Families receive closure at burial services

As a U.S. Marine Corps band played taps and a hawk circled overhead, Phillip Dale Tycz said he felt his brother had finally come home.

“This is where I thought he belonged — not Vietnam ,” Tycz said.

For nearly four decades, the remains of Tycz’s younger brother, Marine Sgt. James Neil Tycz, 22, of Milwaukee , had been missing on a hill in Vietnam , along with those of three other servicemen killed in a firefight May 10, 1967.

On Tuesday, there were burial services for three of the men at Arlington National Cemetery ; the fourth had his service in his hometown of San Jose last month. A painstaking recovery effort by the military led to the identification of the remains earlier this year, using dental records.

“What came home physically was one tooth,” said Irene Healea, whose younger brother, Marine Second Lieutenant Heinz Ahlmeyer Jr., 23, of Pearl River , New York, was killed in the fight on Hill 665, near the Laotian border. “But what really came home was his embodiment and his spirit.”

More than 100 family members and friends came to pay their respects Tuesday, the 38th anniversary of the four young men’s deaths. Just before the service began, a Pentagon helicopter buzzed nearby, its whir-whir-whir a reminder of the fateful day in which a chopper retrieved the three survivors of the seven-man reconnaissance team, leaving the four dead behind. It was too dangerous to go back for them.

The silver-colored coffins reflected the sunlight of a perfect spring day, as a Marine marching band led a procession on the way to the grave site. Members of the POW-MIA group Rolling Thunder placed beads on the coffins. Each family was presented with a folded U.S. flag.

“The flag-folding was like watching a ballet,” said Sandy Keheley, the older sister of 20-year-old U.S. Navy corpsman Malcolm Miller, of Tampa, Florida “Seeing my brother as a hero today and not a statistic meant a lot to me. I feel his spirit is here. He’s on American soil.”

Marine Lance Corporal Samuel Sharp Jr., 20, of San Jose , California, was buried last month alongside his family members, but he was honored along with the other three at Arlington National Cemetery.

Sharp’s mother, Irene Sharp, said Tuesday was not a sad day.

“It’s been a relief to me,” she said. “No tears shed. Finally, he’s home.”

Sharp decided to sign up for the Marines after his best friend, Ed Charette, did. On Tuesday, Charette recalled telling his buddy: “What if you get killed, Sam? I’ll feel really bad.”

“I wish Sam and I had been here together to watch somebody else’s funeral,” Charette said. “I loved that guy.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard