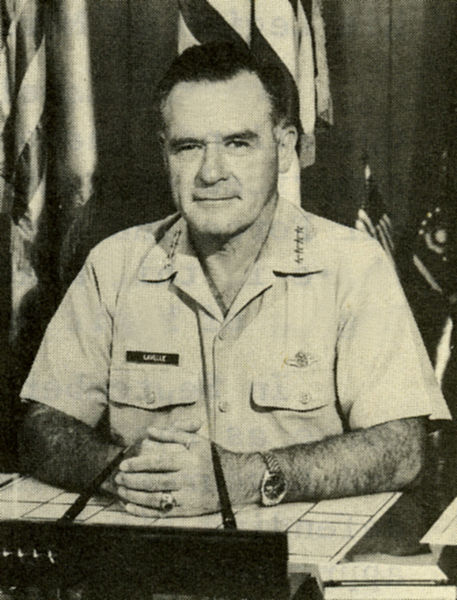

During the summer of 1972, official Washington was dragging Air Force General John D. Lavelle’s name and reputation through the mud. Multiple investigations by the Pentagon and Congress concluded that the four-star commander had ordered unauthorized bombing missions in North Vietnam and then tried to cover them up. He was demoted to major general and forced to retire, in disgrace.

On Wednesday, after an exhaustive reexamination of Lavelle’s actions, President Obama asked the Senate to restore his honor and his missing stars. The decision officially sets the record straight about who really lied during the controversial chapter in the Vietnam War, who told the truth and who was left holding the bag.

Historical records unearthed by two biographers who came across the material by happenstance show that Lavelle was indeed acting on orders to conduct the bombing missions and that the orders came from the commander in chief himself: President Richard M. Nixon.

Not only did Nixon give the secret orders, but transcripts of his recorded Oval Office conversations show that he stood by, albeit uncomfortably, as Lavelle suffered a scapegoat’s fate.

“I just don’t want him to be made a goat, goddamnit,” Nixon told his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, on June 14, 1972, a few days after it was disclosed that Lavelle had been demoted for the allegedly unauthorized attacks. “You, you destroy a man’s career. . . . Can we do anything now to stop this damn thing?”

On June 26, Nixon’s conscience intervened in another conversation with Kissinger. “Frankly, Henry, I don’t feel right about our pushing him into this thing and then, and then giving him a bad rap,” the president said. “I don’t want to hurt an innocent man.”

But Nixon was unwilling to stand up publicly for the general. With many lawmakers and voters already uneasy about the war, he wasn’t about to admit that he had secretly given permission to escalate bombing in North Vietnam. At a June 29 news conference, he was asked about Lavelle’s case and the airstrikes.

“It wasn’t authorized,” Nixon told the reporters. “It was proper for him to be relieved and retired.”

In testimony and in interviews before his death in 1979, Lavelle took responsibility for the military consequences of the bombings, which he said were justified to protect U.S. air patrols and surveillance missions over North Vietnam. But he insisted that he never exceeded his authority. He said he was following rules of engagement communicated to him by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington as well as by Defense Secretary Melvin R. Laird and General Creighton Abrams. (There is no evidence that Lavelle ever knew that the directive originated with Nixon.)

“It is not pleasant to contemplate ending a long and distinguished military career with a catastrophic blemish on my record,” Lavelle told Congress, “a blemish for conscientiously doing the job I was expected to do.”

Removal of that blemish began in 2007, when Aloysius Casey, a retired Air Force general, and his son, Patrick Casey, wrote an article in Air Force Magazine about the case. While researching a biography about another Air Force commander, the Caseys came across audio recordings of Nixon’s conversations as well as declassified message traffic from the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The material, they concluded, showed that Lavelle had “unequivocal authorization” from Nixon and senior military officials to conduct the North Vietnam airstrikes in late 1971 and early 1972.

The findings were presented to Lavelle’s widow, Mary Jo, now 91 and a resident of Marshall, Virginia, as well as the couple’s seven children. The family retained Patrick Casey, a Pennsylvania lawyer, to help them ask the Air Force to reopen the case and restore Lavelle to the rank of full general.

The Lavelles applied to the Air Force Board for the Correction of Military Records, which endorsed the general’s exoneration last year. That decision was separately upheld by Air Force Secretary Michael B. Donley and Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates. On Wednesday, Obama gave his support as well. The case will now go to the Senate for final approval.

“Jack was a good man, a good husband, a good father, and a good officer,” Mary Jo Lavelle said in a statement Wednesday. “I wish he was alive to hear this news.”

Air Force officials said the Lavelle family does not stand to benefit financially from his posthumous promotion. Although he was demoted, military personnel rules in effect at the time enabled Lavelle to retire with a full pension, said Beth Gosselin, an Air Force spokeswoman.

Senator James Webb (D-Virginia), a Vietnam combat veteran who had urged the Air Force to hear Lavelle’s petition, said the case is an example of the frustrations encountered by military commanders during Vietnam who thought they were given conflicting directions from lawmakers and civilian officials.

“We’ve still got a lot of unwinding to do from the debates at the end of the Vietnam War,” Webb said. “But this restores his honor.”

RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS

AIR FORCE BOARD FOR CORRECTION OF MILITARY RECORDS

IN THE MATTER OF:

JOHN D. LAVELLE

(DECEASED)

DOCKET NUMBER: BC-2008-03624

INDEX CODE: 100.00

COUNSEL: PATRICK A. CASEY

HEARING DESIRED: YES

APPLICANT REQUESTS THAT:

Her late husband’s records be corrected to reflect the Secretaries of the Air Force and Department of Defense (DoD)

recommended to the President of the United States that he be posthumously nominated to the grade of general (0-10).

APPLICANT CONTENDS THAT:

The decision to not advance her late husband to the grade of general on the retired list for ordering North Vietnam bombing

missions contrary to the Rules of Engagement (ROE) was based on woefully incomplete evidence, as a result of the DoD withholding evidence from the Senate during an election year for political reasons. Recently obtained evidence, i . e. , white House tapes, con£ irms he was a ‘scapegoat,” and in fact had acted within the authority expressly granted to him by the President and communicated to him through classified communications between the Chief of Pacific Command, the Secretary of Defense, and others.After reviewing the white House tapes, the former Secretary of Defense (SecDef) during the period in question stated in an A i r Force Magazine article that, “General Wheeler (JCS until 1970) , Admiral Moorer (JCS after 1970), and General Abrams (Commander Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV)) all agreed with the liberal interpretation of my order on “protective reactions.”

The new orders permitted hitting anti-aircraft installations and other dangerous targets if spotted on their missions, whether

they were activated or not.” The Former General Counsel to the United States Senate Armed Services Committee, Mr. Woolsey, reviewed pertinent portions of the new evidence and indicated that, “Had I understood this in 1972 I would have recommended to the Committee that [applicant] should have been advanced on the retired list to his full grade. I feel confident that such a recommendation would have been approved by the Committee.”

A former Congressional member of the House Armed Services Committee reviewed the new evidence and indicated, ‘If I had the

White House tapes at the time I would have been even angrier at President Nixon and Secretary Kissinger for turning [applicant]

loose and then hanging him out to dry by denying they had done SO.”

Applicant’s complete submission, with attachments, is at Exhibit A.

STATEMENT OF FACTS:

The member was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Army Air Corps on 21 June 1940. He was integrated into the Air Force

upon its creation in 1947 and was progressively promoted to the permanent grade of major general on 10 February 1966 and to the temporary grade of lieutenant general on 29 May 1968.

Under the 1968 Rules of Engagement (ROE) , planes could not open fire or drop their bombs unless they were: 1) fired upon by anti-aircraft emplacements, 2) engaged by MiG fighters in the air, or 3) threatened by surface-to-air (SAM) missiles. Pilots could readily tell when they were in danger from SAMs because an indicator on their control panel would automatically light-up when a SAM’S tracking radar locked onto their planes. Any of these three conditions entitled pilots to take “protective reactions” and to use their ordnance against the enemy. For years Hanoi had utilized a nationwide Ground Controlled Intercept (GCI) system, which when working properly could detect most U.S. planes long before crossing the De-Militarized Zone (DMZ) . However, in mid-December 1971, Hanoi began “netting” the radar into the lock-on radar capability of each local SAM site; thereby, alerting the SAM crews when a U.S. plane was coming within range. As a result, the general system guided missiles could destroy U.S. aircraft without the SAM sites using their own radar, which provided no warning to U.S. aircrews.

On 1 August 1971, the member was appointed to the grade of (temporary) general and was assigned as the Commander, Seventh

Air Force, and Deputy Commander for Air Operations, MACV, at Tan Son Nhut Airfield, Republic of Vietnam.

Based on allegations that he had conducted unauthorized raids against North Vietnam between November 1971 and March 1972, in violation of the 1968 Rules of Engagement (ROE), and’ had authorized the falsification of reports, the Air Force Chief of

Staff (CSAF), General Ryan, summoned him to the Pentagon to discuss the irregularities. He reported to the CSAF that

Seventh Air Force had conducted a relatively small number of strikes under “protective reaction,” and that aircrews were

advised to report the activation of hostile enemy radar as an enemy reaction.

The CSAF offered him the option of reassignment at his permanent grade (lieutenant general), or retirement. On 31 March 1972, the member applied for retirement. A Medical Evaluation Board (MEB) convened on 5 April 1972 based

on multiple complaints, to include early warning signs of coronary artery disease and progressively more severe limitation

due to pain and stiffness in the lower back and right hip. The MEB recommended the member be referred to a Physical Evaluation

Board (PEB) based on the following diagnoses; moderate coronary artery disease associated with probable angina pectoris,

degenerative disc disease of two levels of lumbar spine, chronic recurrent degenerative osteoarthritis with pain and limitation

of motion, chronic progressive painful limitation of motion in right hip, mild aortic stenosis, sub-acute medial epicondylitis

of left elbow, moderate pulmonary obstructive defect, severe high frequency hearing loss, cervical degenerative disc disease,

multiple tendinitis of both shoulders and right elbow, decreased visions, and mild degenerative osteoarthritis of right knee,

both feet, both shoulders and elbows. On 6 April 1972, a PEB recommended that he be permanently retired by reason of physical disability, with a 70 percent compensable rating, based on the diagnoses of arteriosclerotic heart disease, degenerative disc disease, neuritis, degenerative arthritis of the right hip, and chronic bronchitis. The member concurred with the recommended findings of the PEB. On 6 April 1972, the Air Force Personnel Board concurred with the findings and recommendations. On that same date, the Secretary of the Air Force Personnel Council announced the decision of the Secretary of the Air Force to approve the recommendation of the PRC and to retire him under the provisions f 10 USC 1201, effective 7 April 1972. On 15 May 1972, the Air Force publicly announced the member was retired for personal and health reasons, and that he had been relieved of command because of irregularities in the conduct of his command responsibilities.

On 12 June 1972, the Armed Services Investigating Subcommittee for the Committee on Armed Services House of Representatives, held a hearing to investigate the specific “irregularities. ” The CSAF and the member were the only witnesses. The

subcommittee noted the DoD did not comply with their request for a copy of the summary of the pertinent ROE.

Although nominated for retirement in the grade of lieutenant general (0-9), in a vote of 14 to 2, the Senate Armed Services

Committee (SASC) declined to retire him in that grade. He retired by reason of physical disability in the grade of major general (0-8) effective 7 April 1972, under Title 10, United States Code, Section 1201 and Air Force Manual 35-7. He completed a total of 32 years, 6 months, and 14 days of active service.

AIR FORCE EVALUATION:

AF/JAA opines the weight of the evidence supports restoring the member’s retired grade to the highest grade served (general),

since his retired grade was the result of both error and injustice. The application is based largely on revelations contained in recently-released Nixon White House tapes and wartime military message traffic. This evidence indicates that President Nixon personally told National Security Advisor Kissinger and U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam Bunker to relay to the combatant commander in Vietnam his approval to strike any Surface-to-Air Missile (SAM) site, whether or not it had locked on, and to characterize these strikes as “protective reactions” and the SecDef personally told the member to liberally interpret the ROE. The former SecDef confirmed, after reading the A i r Force Magazine article that all the senior commanders ‘…agreed with the liberal interpretation on my order on “protective reactions.” The new orders permitted hitting anti-aircraft installations and other dangerous targets … whether they were activated or not.”

During the intense Congressional and media scrutiny of the member’s alleged usurpation of civilian control of the military, President Nixon repeatedly told his senior staff that he did not want the member to be “made the goat” for doing what he had been ordered to do. Nevertheless, President Nixon ultimately did nothing to follow through or intervene in what was happening to the member. The information contained in the White House tapes corroborated what the member had maintained all along, i.e., that he had been authorized to bomb the targets and to instruct Air Force crews to file post-mission reports characterizing the attacks as they did.

Perhaps the most telling piece of evidence in support of the application other than the White House tape transcripts is an

extraordinary memorandum from the SASC General Counsel at the time of the member’s confirmation. In this memorandum, the

former SASC General Counsel flatly and persuasively opines that had the information revealed in the White House tapes been

available to the SASC, the confirmation outcome would have been different. The evidence suggests the lower retired grade

recommendation may have reflected politically-based decisions relative to keeping matters out of public awareness at a time when the Vietnam War was problematic for the administration. It is also abundantly clear that whatever process took place,

senior Air Force and DoD leadership relied on inaccurate information in recommending the member retire in a lower grade.

Whether they knew it was inaccurate and possibly flatly untrue is not particularly relevant. If they did, that simply exacerbated the error or injustice. It is unclear from the evidence whether the member was afforded any kind of due process, e. g., an opportunity to rebut the decision to recommend his retirement at a lower grade than highest served, or whether he simply acquiesced to the least repugnant of the alternatives. Normally, their analysis would recite the “presumption of regularity” as limiting the validation of the retired grade recommendation and as therefore limiting to lieutenant general the maximum retired grade to which his grade should be corrected. Here, however, the evidence suggests the presumption has been rebutted, for at least two related reasons. First, it is reasonable to conclude that separate agendas (political, professional, and personal) of the Executive branch officials

involved tainted his removal from command, the process by which the recommended retired grade was determined, and the Senate

confirmation process. Second, that retired grade recommendation effectively limited the Senate’s ability to consider retiring

him in a higher grade. The applicant has clearly met her burden of demonstrating the existence of an injustice that almost certainly adversely affected her husband’s retirement grade. Even if one concludes that her husband’s retired grade would not likely have been different, there is no escaping the conclusion the processes by which he was judged were deficient in that highly–even

critically–relevant information was unknown or ignored by, or withheld from, decision-makers. Both the House and the Senate

requested information in possession of the DoD that could have been critical to, if not dispositive of, the issues underlying

consideration of the grade at which he would be retired. That information was not released.

Much weight is given to the statement from the former SASC general Counsel that had the information been released, the

outcome for the member would almost certainly have been different. A member of the House Armed Services Committee (HASC)

who took part in the House investigation characterized President Nixon and Secretary Kissinger as having ‘…turned [the member]

loose and then hanging him out to dry …” after he became aware of the contents of the White House tapes. Reasonable minds

might, of course, disagree about the significance of details of isolated individual missions and after-action reports. These are

marginal, rather than dispositive considerations, in their opinion. They do exist, however, but do not override the error or injustice resulting fro the withholding of significant information favorable to the member available at the time. Although the applicant asserts that an AFBCMR correction automatically triggers entitlement to compensation under 10 U.S.C. Section 1552(c), she will only be entitled to financial adjustments if, and to the extent that, a records correction in her favor warrants such compensation in order to make her late husband’s record whole. For example, restoration of grade via records correction might generate restoration of pay, but here, any grade restoration would require additional action external to the Air Force, specifically, Presidential nomination, Senate confirmation, and (posthumous) appointment. Should the AFBCMR conclude the applicant’s husband suffered an

error or injustice, corrective action is warranted as the Board is obligated to correct any error or injustice it finds. One alternative is to correct the records to reflect restoration of either the highest grade held (general) or retired grade for which he was nominated (lieutenant general). The better (i.e., more pragmatic) alternative, they believe, would be for the AFBCMR to correct the records to show the applicant’s late husband was nominated for retirement in the grade of general (assuming the AFBCMR concludes, as they do, the retired grade recommended in 1972 was a product of error or injustice). In either case, nomination, confirmation, and (posthumous) appointment are required in order to make the correction a reality and it would be prudent for the AFBCMR to recognize that in any correction that involves restoration of a higher retired grade.

The AF/JAA evaluation is at Exhibit C.

APPLICANT’S REVIEW OF AIR FORCE EVALUATION:

Counsel completely agrees with the advisory opinion and is pleased with the conclusion reached in it. As such, counsel provides no rebuttal comments. However, he questions the reference to Laos, as the propriety of the member’s actions was questioned only as to bombing in North Vietnam and wonder if its inclusion is inadvertent.

Counsel’s complete response is at Exhibit E.

THE BOARD CONCLUDES THAT:

1. The applicant has exhausted all remedies provided by existing law or regulations.

2. The application was not timely filed; however, it is in the interest of justice to excuse the failure to timely file.

3. Sufficient relevant evidence has been presented to demonstrate the existence of error and injustice. Af ter

thoroughly reviewing the evidence of record and noting the applicant’s contentions, we find sufficient evidence the retirement grade in which the member was nominated was the result of material error – an incomplete record. In this respect, we note the member was relieved of his command and retired in the grade of major general based on the results of an Air Force Inspector General investigation which concluded that he had authorized pilots to bomb targets in North Vietnam contrary to the standing ROE and to falsify their after-action reports. However, based on recently obtained documentation, it is clear the White House, the Department of Defense, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) all possessed evidence which, if released, would have exonerated him. This evidence indicates the bombing missions into North Vietnam were authorized by then President Nixon who personally told National Security Advisor Kissinger and U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam Bunker to relay to the combatant commander in Vietnam that, ‘…protective reaction should include preventative [sic] reaction …” and that “He can hit SAM sites period. ” The evidence indicates that on 8 November 1971, the Chairman of the JCS, Admiral Moorer, personally approved the member’s request to attack the MiG airfield at Dong Hong and reviewed the bomb damage assessments (BDAs) the day of the attack. There is no evidence of any

concerns by the JCS. To the contrary, they simply suggested more careful planning. Later that same month, the Commander, United States Pacific Command, Admiral McCain voiced his deep concerns to the Chairman of the JCS concerning the protection of the B-52 force based on the mounting threat of the integrated netted” air defense network the North Vietnamese had begun

employing, which virtually eliminated any earlier warning of attack upon U. S. aircraft; however, his request was denied. The

following month the SecDef met with the member and he was told to liberally interpret the ROE and he would back him up. He

spoke with the Commander of MACV, General Abrams, who agreed with the SecDef. In view of this and given strong evidence the North Vietnamese were preparing a massive conventional attack on the south, he directed a pre-planned “protective reaction”

strike after sustaining losses of two AC-130 gunships and an RF-4C fighter due to ground fire and MiG attack. The documentation

before us contains two pieces of substantial evidence upon which we place great weight – the statements from the former SecDef

and former General Counsel to the SASC. In his letter to Air Force magazine, the former SecDef states that he told the m e m E

to liberally interpret his order on “protective reactions” to permit hitting anti-aircraft installations and other dangerous targets, whether they were activated or not; and General Wheeler (the Chairman of the JCS prior to 1970), Admiral Moorer (Chairman of the JCS af ter 1970) , and General Abrams (MACV) all agreed with the liberal interpretation. The Former General Counsel to the SASC, Mr. Woolsey, has reviewed the pertinent portions of the new evidence and indicates that had he been aware of this in 1972 he would have recommended the Committee advance the member on the retired list to his full grade and feels confident that such a recommendation would have been approved. In adjudicating this case a number of troublesome issues came to light, i .e., (1) why did they not prefer courtmartial charges against the member?; (2) did the Air Force Chief of Staff (CSAF) know the member had obtained prior approval from the President?; and, (3) why was the member punished but not other officers? Based on the totality of the evidence presented, it would appear the decision to not prefer courtmartial charges against the member may have been based on a finding the charges would not have passed the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard of the court; or, that evidence existed which sustained his innocence. It also appears General Ryan (CSAF) may not have known the member was acting on orders from the President and SecDef, or if he did, simply chose to ignore these facts during his testimony before Congress. The Congressional testimony indicates the CSAF never discussed the ROE with the member or had even seen the ROE. With respect to any

p unishment of other officers, we find no evidence that other personnel involved were ever punished after the member stepped

forward and accepted full responsibility. In fact, during his testimony before Congress he stated, ‘…these are hard-working,

wonderful Air Force people, who made their interpretation of what they thought we wanted.” Based on the evidence of record,

it is clear the decision to not revise the ROE to authorize bombing missions into North Vietnam was based on political reasons, rather than operational requirements. Although the President had previously authorized the bombings, it appears he too did nothing to intervene in the member’s behalf since it was an election year and he would soon be embarking on his historic trip to the Peoples Republic of China – the first such visit for an American president. Therefore, we find the member did act on a lawful order from the Commander-in-Chief. As such, the only remaining issue before us is the allegation that he authorized the falsification of after-action reports. Although he did tell his personnel they could not report “no enemy action,” the evidence before us indicates that he was referring to the fact the North Vietnamese integrated “netted” air defense network constituted an automatic activation against U.S. aircraft; thus, complying with the ROE. There is no evidence he caused, either directly or indirectly, the falsification of records, or that he was even aware of their existence. To the contrary, once it was brought to his attention, he immediately took action to insure the practice was discontinued and took full responsibility, stating that as the commander he should have known. Moreover,

there is absolutely no evidence that he ever participated in any cover-up or impeded the investigation in anyway. We also find

it most important to note that it is obvious he was prescient in carrying-oit the President’s orders as evidenced by the fact that shortly after his retirement, bombing of North Vietnam returned on an un-restricted basis, without the pre-condition of enemy reaction. In arriving at our decision, we are keenly aware the courts have long held this Board has an abiding moral

sanction to determine, in so far as necessary, the true nature and impact of the error or injustice and to take appropriate steps to insure the record is corrected and full and effective relief is granted; and, that when we fail to correct an injustice clearly presented in the record before us, we are acting in violation of our mandate. In view of the above and based on a totality of the evidence presented, we agree with the comprehensive comments of the Director, Administrative Law (AF/JAA) and believe the applicant has sustained her burden of establishing the existence of an error and an injustice in her late husband’s records. Therefore, we recommend the member’s records be corrected to the extent indicated below. However, as indicated by AF/JAA, monetary award through the correction of records process is not automatic and the applicant will only be entitled to such financial adjustments if, as a result of the corrections to her late husband’s records, such compensation is warranted in order to make her late husband’s record whole. We also note our decision will consist of two parts which reflect the limits of the authority of the Secretary of the Air Force to effect the record correction we have determined is necessary.

4. The applicant’s case is adequately documented and it has not been shown that a personal appearance with or without counsel

will materially add to our understanding of the issues involved. Therefore, the request for a hearing is not favorably considered.

THE BOARD RECOMMENDS THAT:

The pertinent military records of the Department of the Air Force relating to MEMBER, be corrected to show that the Secretary of the Air Force recommended that the President nominate him to be retired in the grade of general (0-10) and that action be initiated to obtain Senate confirmation. It is further recommended that such a recommendation be forwarded to the Secretary of Defense, together with a copy of the record of the Air Force Board for Correction of Military Records, and that all other actions within the authority of the Air Force be taken with a view to securing his nomination, confirmation and appointment to the grade of general.

It is further recommended that should he be advanced on the retired list to the grade of general by appointment of the President, his records should be corrected to show that he was retired in the grade of general, effective 7 April 1972, -;;lder the provisions of Section Z201, Title 10, Vcited Stat-es Code.

The following members of the Board considered AFBCMR Dockel.

Number BC-2008-03624 in Executive Session on 10 Aprii 2CC9,

under the provisions of AY1 36-2603:

Mrs. Barbara A. Westgate, Panel Chair

Mr. Michael J. Novel, Member

Mr. Anthony P. Reardon, Member

All members voted to correct the records, as recorrmended. ‘I’hat,

foliowing documentary evidence of BC-2008-03624 was considered:

Exhibit A. DD Form 149, dated 7 Sep 08, w/atchs.

Exhibit B. M e n i b e r ‘ s Master Personnel R e c o r c l s .

Exhibit C. Memorandum, Hq USAF/JAA, dated 20 Mar 09.

Exhibit D. Letter, SA?/MRBR, dated 25 Mar 09.

Exhibit E. Letter, Counsel, 27 Mar 09.

BARBARA A. WESTGATE

Panel Chair 0

EPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE

WASHINGTON, DC

Office of the Assistant Secretary

AFBCMR

1535 Command Drive

EE Wing, 3rd Floor

Andrews AFB MD 20762-7002

OCT 3 0 2009

Mrs. Mary J. Lavelle

C/O Mr. Patrick A. Casey

Myers, Brier & Kelly, L.L.P.

425 Spruce Street, Suite 200

Scranton, PA 18503

Dear Mrs. Lavelle

Your application to the Air Force Board for Correction of Military Records, AFBCMRBC-2008-03624, has been finalized. The Board determined that the military records should be corrected as set forth in the attached copy of a Memorandum for the Chief of Staff United States Air Force.

Please be aware that it is beyond the authority of the Department of the Air Force to retire General Lavelle in the grade of general (0-10). Such action will require Presidential nomination and Senate confirmation. However, the appropriate Air Force office will take the action required to initiate the nomination, confirmation and appointment process.

In the event General Lavelle is advanced to the retired grade of general, the pertinent military records of the Department of the Air Force will be corrected as set forth in the attached memorandum and the office responsible for making the correction will inform you when the records have been changed.

Because of the complexity of the nomination, confirmation and appointment process, you should expect some delay. We assure you, however, that every effort will be made to conclude this matter at the earliest practical date.

PHILLIP ORT TON

Deputy Executive Director

Air Force Board for Correction of Military Records

Attachments:

1. Record of Proceedings

2. Copy of Directive

cc:

Mr. Patrick A. Casey

Born at Cleveland, Ohio, September 9, 1916, he received a B.S. degree from John Carroll University, Cleveland, and received postgraduate training at George Washington University in 1935. He graduated from the Air War College in 1957. He married Mary Josephine McEllin, June 22, 1940.

He was commissioned a Second Lieutenant, United States Army Air Corps, 1940, and advanced through the grades to Major General, United States Air Force, 1965. He was commander, 6411th Supply Group, Tachikawa Air Force Base, Japan, 1951-52; 568th Air Defense Group, McGuire Air Force Base, New Jersey, 1952-53; Deputy Commander and Commander, 1611th ATW, McGuire AFB, 1954-56; Deputy Director of Requirements, Headquarters, USAF, 1957-58; Weapons Board, USAF, 1969-61; Deputy Director of Programs, USAF, 1961-62; Director, Aerospace Programs, USAF, 1964-66; Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, Headquarters, 4th Tactical Air Force (NATO), Ramstein AFB, Germany, 1962-64; Commander, 17th Air Force, from 1966; later commanded the 7th Air Force in Southeast Asia.

He retired as a Lieutenant General in 1972. He had been a full General but was reduced in rank after a controversy over his command style in Vietnam when it was alleged that he had overstepped his command authority in ordering bombing runs in and around that country. During his career, he was awarded the Legion of Merit with 2 oak leaf clusters, the Air Medal with oak leaf cluster, and the Belgian Fourragere.

He resided in Fairfax, Virginia, and died on July 10, 1979. He is buried in Section 11 of Arlington National Cemetery.

Courtesy of the United States Air Force

GENERAL JOHN D. LAVELLE

Retired April 7, 1972, Died July 10, 1979

General John Daniel Lavelle was commander of Seventh Air Force, with headquarters at Tan Son Nhut Airfield, Republic of Vietnam. He is also deputy commander for air operations, U.S. Military Assistance Command in Vietnam. As Seventh Air Force commander, he is responsible for all Air Force combat air strike, air support and air defense operations in mainland Southeast Asia. In his MACV capacity, he advises on all matters pertaining to effective use of tactical air support and coordinated Vietnamese Air Force and U.S. air operations of all units in the MACV area of responsibility.

General Lavelle was born in 1916, in Cleveland, Ohio, where he attended Cathedral Latin High School, and graduated from John Carroll University in 1938 with a bachelor of science degree. In 1939 he enlisted as an aviation cadet in the Army Air Corps and received pilot training at Randolph and Kelly fields, Texas. He received his pilot wings and a commission as a second lieutenant in June 1940.

He returned to Randolph Field as a flying instructor and in 1942 was assigned as part of a cadre to open Waco Army Air Field, where he served as squadron commander and director of flying. During World War II he saw combat in the European Theater of Operations, where he served with the 412th Fighter Squadron.

In January 1946 he was assigned to Headquarters Air Materiel Command at Wright Field, Ohio, as Deputy Chief of Statistical Services. When the U.S. Air Force was established as a separate Service in 1947, he was one of the two Air Force officers who negotiated with all seven Army Technical Services and wrote the agreements for the division of assets and the operating procedures to be effected during the buildup of the Air Force.

He was assigned in October 1949 as the Director of Management Analysis And later as the comptroller of the Far East Materiel Command at Tachikawa Air Base, Japan. During the Korean War, he was made commander of the Supply Depot at Tachikawa. In this assignment, he was awarded the Legion of Merit for the reorganization of the theater supply system and the establishment of a procedure for control of the transshipment of supplies direct from the United States to Korea.

In November 1952 he was assigned as commander of McGuire Air Force Base, N.J., and the 568th Air Defense Group. During his tenure there, the Military Air Transport Service facilities and air terminal were constructed and McGuire Air Force Base became an East Coast aerial port. When the base was transferred to MATS, he became the MATS Transport Wing commander. While at McGuire Air Force Base, he established a community relations program which did much to ease the problems that normally befall an area where a military installation grows from approximately 1,500 to 10,000 personnel. General Lavelle is still considered an honorary citizen of many of the small communities around McGuire and an honorary member of the local Lions International and Kiwanis Club.

He attended the Air War College in 1956-1957 and then spent the next five years at Headquarters U.S. Air Force as deputy director of requirements; secretary of the Weapons Board; and deputy director of programs. While in the Pentagon, he was principally responsible for the reorganization of the Air Force Board system and the establishment of program control through the Program Review Committee and the Weapons Board. He was awarded an oak leaf cluster to his Legion of Merit at the end of this tour of duty.

General Lavelle went to Europe in July 1962 as deputy chief of staff for operations, Headquarters Fourth Allied Tactical Air Force, NATO, which was comprised of numbered Air Force-size elements of the German, French and Canadian Air Force and the U.S. Air Forces in Europe. For his accomplishments while in this headquarters, he was awarded a second oak leaf cluster to his Legion of Merit and the “Medaille de Merite Militaire” by France.

In September 1964 General Lavelle was assigned to Headquarters U.S. Air Force as the director of aerospace programs, Deputy Chief of Staff for Programs and Resources. As director, he was principal backup witness in presenting and defending Air Force programs to the congress after such programs had been approved by the secretary of the Air Force and the secretary of defense. In addition, he served as chairman, Air Staff Board, and as chief, Southeast Asia Programs Team.

Command of the Seventeenth Air Force, headquartered at Ramstein Air Base, Germany, was General Lavelle’s next assignment in July 1966. Seventeenth’s operations spanned Germany, Italy and Libya. In this position, General Lavelle commanded a versatile, combat-ready force equipped with supersonic jet fighters and tactical missiles with nuclear, conventional and air-to-air capabilities. Seventeenth Air Force is a NATO-committed major subcommand of USAFE, one of America’s strongest overseas air arms and a primary instrument of Western defense.

In December 1967 General Lavelle was assigned to the Defense Communications Planning Group located at the Naval Observatory, Washington, D.C., where he served as the Deputy Director for Forces. In February 1968 he assumed duties as the director of the Defense Communications Planning Group.

General Lavelle was assigned as vice commander in chief, Pacific Air Forces, with headquarters at Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii in September 1970. He served in that capacity until assuming command of Seventh Air Force July 29, 1971.

He is a command pilot. His military decorations and awards include the Distinguished Service Medal, Legion of Merit with three oak leaf clusters, Air Medal with oak leaf cluster and Air Force Commendation Medal with oak leaf cluster.

LEADERSHIP BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE

MAJ LEE E. DEREMER, USAF

Integrity requires the courage of sometimes saying no-or at least apersistent asking “why?”- from all of us to others of us who institute unexamined regulations that often require “no-win” solutions for both the system and personal integrity.

-Richard D. Miller,

Chaplain, Colonel, USAF

WHAT IF AN operational leader told you that he had such conflicting demands that he was in a “no-win” dilemma? He could satisfy either demand but not both-and to fail to satisfy either would exact great professional and personal cost.Most people would say something like, “Sure, there’s a solution. You just haven’t considered all your options. Innovate. Improvise.” Whatever the words, the message would be the same: find a solution. We expect that; it’s our culture.

Our mind-set envisions success in spite of external constraints. The overriding assumption is that solutions to dilemmas do exist and that these solutions will be honorable to all parties without sacrificing the mission. A further assumption is the existence of clearly right and wrong choices in such dilemmas.

Life is not always so tidy. High military rank is often accompanied by competing or even conflicting interests. Problems can arise for which no painless options exist. For example, an organization’s integrity may conflict with constraints that diminish the unit’s safety and mission accomplishment. If that is the case, these demands are mutually exclusive. Since we can’t compromise integrity, we must find a solution to the dilemma by changing the constraints. If that isn’t possible, then rather than compromise integrity, leaders must sacrifice themselves professionally to change the constraints in order to resolve the dilemma and preserve the mission and the safety of their people.

Consider operational leaders faced with the legitimate concern for the effectiveness and safety of people under their command and with externally imposed constraints that not only complicate the mission but also unnecessarily imperil their people. These leaders face two realities. First, they don’t have a lot of options. Second, none of the options are attractive.

General John D. Lavelle faced such a dilemma toward the close of the Vietnam War. As the commander of Seventh Air Force, he was responsible for conducting the air war in Southeast Asia. He was relieved of command on 6 April 1972. The problems he faced, the solution he chose, and the ramifications of his choices offer us lessons about decision making. This honorable officer would be retired as a major general rather than full general-the rank he held as commander of Seventh Air Force. Never before had such an action occurred in American military history

Dilemma

When General Lavelle assumed command of Seventh Air Force in Saigon, South Vietnam, on 1 August 1971, he inherited rules of engagement (ROE) that had evolved over three years. The ROE maintained the basic restrictions of a 1968 agreement by the Johnson administration and consisted of directives, wires, and messages defining the conditions under which US aircraft could attack enemy aircraft or weapons systems. Seventh Air Force consolidated those directives into a manual of “operating authorities” and disseminated it to the units. Aircrews received briefings on the ROE prior to each mission.

Essentially, aircrews could not fire unless they were threatened. Enemy surface-to-air missiles (SAM) or antiaircraft artillery (AAA) had to “activate against” aircrews before they could respond with a “protective reaction strike.” Warning gear installed in the planes alerted aircrews that an enemy SAM firing site was tracking them.

American aircrews lost this advantage late in 1971, when the North Vietnamese took several actions to vastly improve their tracking capability, the most important being the integration of their early warning, surveillance, and AAA radars with the SAM sites. This integrated system allowed the North Vietnamese to launch their missiles without being detected by the radar warning gear of US aircraft.

General Lavelle believed that because those mutually supporting radar systems transmitted tracking data to the firing sites, the SAM system was activated against US aircraft anytime they were over North Vietnam. He also learned, through the bitter experience of losing planes and crews on two occasions, that US aircraft were much less likely to evade SAMs when the radars were so netted. He later testified that this experience provided sufficient rationale for planned protective-reaction strikes, noting that “the system was constantly activated against us.”

The North Vietnamese also improved their tactics by using ground controlled intercept (GCI) radars to track US aircraft. Azimuth information developed by GCI surveillance was fed to fire-control radars. This netting effectively eliminated tracking with the Fan Song radar and allowed more than one missile site to be directed against a single US aircraft. General Lavelle later testified to Congress that he “alerted his superiors to the enemy’s netting of his radars and advised them that the North Vietnamese now possessed the capability of firing with little or no warning.”

The air war had changed. General Lavelle made repeated and futile attempts to get the ROE changed to reflect the new threat to his aircrews and planes. However, not only did Washington refuse to change the ROE but the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) severely criticized General Lavelle for a lack of aggressiveness in fighting the air war. He received a personal visit from the chairman of the JCS, who made it clear that he was to find ways of prosecuting the war more aggressively within the constraints of the ROE. The general had a problem. What took priority: the ROE or the safety and effectiveness of his command?

He chose the latter, authorizing a strike on 7 November 1971-the first of 20 to 28 missions from that date to 9 March 1972. Regarding these missions, Lavelle stated that he “made interpretations of the ROE that were probably beyond the literal intention of the rules.” Each strike involved six to eight aircraft, for a total of 147 sorties out of approximately 25,000 flown during the period. Each mission attacked missile sites, missiles on transporters, airfields, 122 mm and 130 mm guns, or radars.

In response to a JCS inquiry about Seventh Air Force’s authority to strike a GCI site on 5 January 1972, General Lavelle replied that, since his aircraft were authorized to hit radars that controlled missiles or AAA, he believed they were also authorized to strike GCI radars that controlled enemy aircraft. He later received another JCS message that, although sympathetic, said he had no authority to strike a GCI radar and that he should order no such strike again.

When a leader starts cuttingcorners in integrity (intentionally or unintentionally), that action can pervade the entire organization.

Although amended on 26 January 1972 to authorize strikes against primary GCI sites when airborne MiGs indicated hostile intent, the ROE still didn’t address the netted SAM threat. This amendment was as close as General Lavelle got to persuading the JCS to adopt satisfactory rules of engagement.

Consequences

On 8 March 1972, a senator forwarded to the Air Force chief of staff a letter written by an Air Force sergeant-an intelligence specialist in Seventh Air Force. It alleged ROE violations and ongoing falsification of daily reports on missions. The Air Force inspector general (IG) flew to Saigon to investigate the matter and confirmed that “irregularities existed in some of 7th Air Force’s operational reports.” General Lavelle immediately stopped all strikes in question and assigned three men to find a way to continue the protective-reaction sorties but report them accurately. The conclusion was that this couldn’t be done.

On 23 March 1972, General Lavelle was offered reassignment at his permanent grade of major general or retirement. He opted for retirement, effective 7 April 1972. Little did he know what lay ahead.

The Air Force, having already announced that General Lavelle retired for personal reasons, would be forced to admit on 15 May 1972, after congressional inquiry, that the general had not only retired but had also been relieved of command because of “irregularities in the conduct of his command.” This revelation led to hearings before the Armed Services Investigations Subcommittee of the House Committee on Armed Services.

In his statements before the committee, General Lavelle convincingly maintained that he did not order the falsification of any reports. Although he insisted throughout the investigations by the Air Force and Congress that he learned of the falsified reports only after the IG investigation, as commander, he accepted full responsibility for those reports.

Reports on four of the missions were found to contain falsehoods. General Lavelle stated that he traced the probable cause of the false reporting to the first protective-reaction strike, which he had directed from the operations center. When his lead pilot reported by radio that the target had been destroyed and that they had encountered no enemy reaction, the general stated, “We cannot report `no reaction.'” As General Lavelle explained, “I could report enemy reaction, because we were reacted upon all the time [with the existence of the upgraded radar].” Unfortunately, since his instructions to the pilot were vague, aircrews made false statements on some subsequent operational reports.

Congress accepted General Lavelle’s explanation of the confusion over his intent regarding the reporting of the protective-reaction strikes-but only after many months of inquiry. By that time, few people were interested in clearing his name; consequently, General Lavelle would be remembered as someone who disregarded the ROE, fought his own unauthorized war, and made everyone falsify reports to keep it secret.

Although none of these allegations appear to be true, General Lavelle did make mistakes. His first was failing to make clear that Seventh Air Force demanded absolute integrity of its people. Had he done so, there would have been no mistaking his intent concerning operational reports. Indeed, such action might have had the effect of curbing widespread practices-unknown at the time-that were compromising the military’s integrity. Specifically, widespread disclosures were made of illegal bombing and falsification of official records of these illegal raids, which had been going on for years before General Lavelle even appeared on the scene. These revelations caused the chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee to drop his probe in August 1973. According to the chairman,

“Air Force and Defense witnesses gave us to believe that falsification was so rare and so contemptible that it was good cause to remove General Lavelle from his command and drum him out of the service because he had ordered documents falsified.” However, the chairman’s decision didn’t even merit publication in any of the papers or periodicals that had previously convicted the general in print.

His second mistake lay in choosing to work around the ROE to accomplish the mission yet keep his crews safe. That meant bending the unrealistic ROE, an action that produced both positive and negative results.

From a positive viewpoint, despite the vastly improved North Vietnamese air defenses, no American lives or aircraft were lost during the raids in question. To that extent, General Lavelle’s decision had the desired effect. Ironically, the conditions for protective-reaction strikes-relaxed in January 1972, as mentioned above-were abolished in March 1972, but not before the issue of integrity in reporting would cost General Lavelle his command.

General Lavelle’s actions also had negative effects that he had no way of foreseeing. Therein lies the danger of working around bad ROE rather than having them changed. His decision to “interpret the ROE liberally” had several ramifications.

It led to continuing decay of the command’s integrity, which contributed to the falsification of operational reports, which led to the sergeant’s letter to the senator, which led to the IG investigation, which led to Lavelle’s being relieved of command, which the Air Force kept secret, which led to a congressional investigation. This phenomenon is now commonly referred to as the “slippery slope effect.” That is, when a leader starts cutting corners in integrity (intentionally or unintentionally), that action can pervade the entire organization.

A commandwide climate of integrity is indispensable.

For General Lavelle, it would get much worse. By this time, he really had no control of events, and some of the ramifications of his actions could have had strategic implications for peace negotiations and the credibility of the armed services.

Specifically, at the same time General Lavelle began strikes on the newly integrated radar-SAM/AAA network, Henry Kissinger was in Paris conducting secret peace talks with the North Vietnamese. General Lavelle had no way of knowing about the talks, and Kissinger didn’t know about the bombing. But Le Duc Tho of North Vietnam knew about both. To him, Kissinger was either lying or very poorly informed. Shortly thereafter, the talks broke off abruptly.

General Lavelle, as well as the Air Force, Army, and Navy, would feel shock waves from his operational decision: Lavelle was accused of criminal misconduct; court-martial charges were filed against him and 22 other officers; the nomination of General Creighton Abrams as chief of staff of the Army was delayed for over four months; the Senate Armed Services Committee conducted an extensive and critical look at the command and control structure of the Air Force; General Lavelle’s retirement rank was reduced to major general; naval aviators said that they had been involved in protective-reaction raids not authorized by the ROE; Department of Defense IGs now reported directly to the service secretaries rather than to their service chiefs; and the Senate Armed Services Committee placed an indefinite hold on promotions for about 160 Air Force officers. Amazingly, none of the threatened action against any of the affected officers came to fruition. Although the investigations were eventually dropped, they underscore the fact that operational decisions are not made in a vacuum and that negative effects, however unintentional, can be extensive.

History places some people incircumstances that require them to choose either to do the right thing or keep their careers intact.

Instead of choosing between continuing the missions under intolerable circumstances or obeying the poor ROE, General Lavelle could have averted the problems listed above by ceasing operations until authorities changed the ROE to reflect the reality of the threat. Doing so would have meant going outside the chain of command when his superiors were unresponsive-an action that almost surely would have cost him his command. The option existed, but he chose not to take it. As it turned out, he lost his command anyway. Had he lost his command while demanding proper ROE, he would have (1) forced a change in the rules instead of leaving them to chance, (2) provided an example of the importance of taking care of people under our command and maintaining integrity, and (3) avoided the personally and strategically undesirable outcomes he could not foresee.

Lessons Learned

Two important lessons should be clear for operational leaders. The first is understanding the importance of integrity at all levels of command. The second is accepting the fact that sometimes leaders may have to sacrifice themselves because it’s the best thing for the organization, the people, and the country.

The first lesson isn’t difficult to understand, but it’s tough to apply because choices aren’t always clear in positions of increased responsibility. Nevertheless, a commandwide climate of integrity is indispensable. To accept anything less than absolute integrity in personal and professional behavior is to invite breakdowns like the one described by the noncommissioned officer who broke the story on false reports in Seventh Air Force:

We went through the normal debrief, and when I asked [the aircrew] if they’d received any AAA, they said, “No, but we have to report it.” I went to my NCOIC and asked

him what was going on. He told me to report what the crew told me to report. . . . The false information was used in preparing the operational reports and slides for the

morning staff briefing. The true information was kept separate and used for the wing commander’s private briefings.

This speaks to the possibility of a wide problem. But in October 1972, the Air Force responded quickly and well to the challenge of reestablishing the standard by sending the following message to all units. It’s as applicable today as it was then:

Integrity-which includes full and accurate disclosure-is the keystone of military service. Integrity binds us together into an Air Force serving the country. Integrity in reporting,

for example, is the link that connects each flight crew, each specialist and each administrator to the commander-in-chief. In any crisis, decisions and risks taken by the highest national authorities depend, in large part, on reported military capabilities and achievements. In the same way, every commander depends on accurate reporting from his forces. Unless he is positive of the integrity of his people, a commander cannot have confidence in his forces. Without integrity, the commander-in-chief cannot have

confidence in us.

Therefore, we may not compromise our integrity-our truthfulness. To do so is not only unlawful but also degrading. False reporting is a clear example of failure of integrity.Any order to compromise integrity is not a lawful order.

Integrity is the most important responsibility of command. Commanders are dependent on the integrity of those reporting to them in every decision they make. Integrity can be ordered, but it can only be achieved by encouragement and example.

I expect these points to be disseminated to every individual in the Air Force-every individual. I trust they help to clarify a standard we can continue to expect, and will

receive, from one another.

That’s the kind of message each commander needs to make clear from the outset-the kind of standard people should demand from each other. Still, a valid question remains: “Who can maintain absolute integrity? Not me and not you, so how useful or realistic is such a demand?” The answer begins with other questions. Without such a standard, how would you introduce yourself to your unit? By telling them you expect “really good integrity,” “their best effort,” “what suits each person”? The point is that the standard for integrity is just that-a standard. None of us will attain it every day, but we gain much by holding it before the unit. Consider this: if the standard doesn’t apply fully and continuously, then what good is it as a core value? Its value exists precisely in its utility.

The second lesson is more difficult to discuss because the object of the lesson-sacrificing one’s career if circumstances require it-is rather unpalatable. Indeed, people are often ridiculed for taking such a stand. Yet, history places some people in circumstances that require them to choose either to do the right thing or keep their careers intact. As the Stoic philosopher Epictetus tells us in Enchiridion, “Remember, you are an actor in a drama of such sort as the Author chooses-if short, then in a short one; if long, then in a long one. If it be His pleasure that you should enact a poor man, or a cripple, or a ruler, see that you act it well. For this is your business-to act well the given part, but to choose it belongs to Another.”

Furthermore, we must recognize that playing the part can exact a great price. Doing the right thing doesn’t always result in accolades. The Book of Ecclesiastes has a simple, timeless message: “I returned and saw that the race is not always to the swift nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise nor riches to men of understanding, nor favors to men of skill, but time and chance happeneth to them all” (9:11). The Book of Job is even more blunt: Job learns that life isn’t always fair and that bad things happen to good people. Despite this realization, people must lead-and they must lead within the roles in which history places them.

Conclusion

Abraham Lincoln once remarked that “if you once forfeit the confidence of your fellow citizens, you can never regain their respect and esteem.” Indeed, as unpleasant as the realization might be, sometimes leaders face dilemmas for which no comfortable solution exists. It’s not entirely fair for me to criticize General Lavelle for his decisions, since I didn’t experience his dilemma. Indeed, if I had to choose between the alternatives he considered, I probably would have made the same choice.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that even if leaders are faced only with gray areas that offer no clear choice, that still does not absolve them from the dilemma. There is a better choice: demand change. If the issue is important enough, the decision maker should demand resolution of unsatisfactory constraints (in this case, the ROE). Even though this option will likely cost the leaders their careers, it is the best decision for the institution and for the people under their command.

This article represents just the first half of the effort. The follow-up work must be an assessment of command ethics. Once we agree that a climate of integrity is a critical leadership issue, we’ll want to measure that climate. Such an assessment must identify valid, reliable indicators of the ethical health of a command. It should highlight positive signs as well as warning flags of behavior that need to be addressed before a problem arises. That, it seems to me, is the key: having enough situational awareness in the command to foresee a problem-or at least to recognize one as it is developing-rather than seeing it only in hindsight.

Each commander can accept this challenge informally while preparing for new levels of leadership. Measuring how well the challenge is met might not be possible. That is, ethical lapses might still occur, and we have no way of knowing whether they would be more severe or more frequent in the absence of such an effort. What is certain, however, is that this examination-both before assuming command and during command-can ultimately groom more professional people and produce more effective units.

I read with interest the article by John Correll on the ouster of General John D. Lavelle (November, page 58). As a Brigadier General in 1968, I was elected by Lavelle as his deputy for operations in the Defense Communications Planning Group (DCPG), which was a cover for the development of seismic and acoustic sensors to detect primarily truck traffic on the roads that made up the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos. It was also known as the Igloo White Project. In 1969-70, he sent me to command Task Force Alpha located at Nakhon Phanom, Thailand. TFA was the infiltration-surveillance center where sensor data relayed through EC-121 aircraft was processed by large computers — the speed, direction, number, and location of the truck traffic, as well as transshipment and storage areas were sent to FACs to direct immediate strikes and to 7th AF for subsequent Arc Light bomber targeting.

This idea was the brainchild of the Scientific Advisory Board and embraced by McNamara who made it a priority development under the direct control of SECAF Harold Brown and using primarily Air Force funds to budget it. General Ryan thought it a flawed concept and a waste of time and Air Force money.

Harold Brown, on one of his visits to 16th AF at Ramstein, had several briefings by then-Major General Lavelle and was astounded by his detailed knowledge of specifications and functioning of every element of weapons systems and operations in 16th AF in response to his, even trivial, questions. Not once did he need the support of any of his staff. He was the consummate micromanager (as was Brown). Therefore, when the position of director of DCPG came open, he personally appointed Lavelle to the job and promoted him to lieutenant general outside of the AF system. This did not sit well with General Ryan, who did not have the same appreciation of Lavelle’s qualifications as the SECAF.

With his close relationship with Brown and knowing that McNamara wanted to accelerate the Igloo White operational date, Lavelle pushed hard and was able to divert valuable AF assets to his program. This also did not please General Ryan. I attended several meetings between the two, and there was no love lost. It was quite apparent to General Ryan that he had little control over Lavelle with his direct access to DOD and Brown, even to his selection and assignment of AF personnel. Also, Lavelle was able to bypass 7th AF/13th AF at Clark AFB and 7th AF in Saigon and personally direct many operations at TFA in Thailand.

In 1971, when the job of commander 7th AF came open, Brown, over Ryan’s objections, appointed Lavelle (who had no operational experience) and promoted him to four stars. So, the battle lines were drawn. All that was left was for Lavelle to “screw up” and Ryan would crucify him. And it happened—there could have been other outcomes less injurious to the Air Force had Ryan not been focused on extracting his pound of flesh. He had every right to be upset by Brown usurping his prerogatives and Lavelle’s freewheeling antics and promotion to full general. But the effective disciplining of the man could have been achieved without all the ruckus, had Ryan used the more subtle pressures at this disposal and a little more political astuteness. In the final analysis, the stalemate was broken when Lavelle, not wanting to fight any longer, compromised—and this is important—he would accept his demotion to major general and retirement if he would get 100 percent military disability (not VA disability), which meant a substantial increase in his total retirement compensation.

In my three years of a very close relationship with General Lavelle, while frustrated by his micromanagement style, I admired his devotion to his job—his job was his life. Seven-day work weeks were the norm, and his workaholic civilian bosses rewarded him accordingly. Supremely confident, he did not fear “stove piping” General Ryan. After all, he got his third and fourth stars!!! On a personal note, being Lavelle’s prime military deputy for those years did not especially ingratiate me with Gen. Ryan or enhance my prospects for further advancement—but it was an intriguing “wild ride” while it lasted.

Brig. Gen. Chet Butcher,

USAF (Ret.)

Fort Myers, Fla.

Regarding the John Correll piece on General John Lavelle and resultant letters, I’m reminded of my first day as AC-47 combat tactics officer at HQ 7th Air Force in late 1968. The directorate’s office was empty save for a clerk and an officer who was composing a trip report that would go directly to the director of operations. In response to my question of “What’s my job?” Major Jerry Watson replied, “Anything you’re man enough to do.”

Anyone having experienced Vietnam (or having read its extensive literature) should realize that General Lavelle and many others were thrust into circumstances that tested their manhood. General Lavelle’s misfortune was that he was not serving under Napoleon, who on November 2, 1809 wrote to Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessieres: “Be of firm character and will. … Overcome all obstacles. I will disapprove your actions only if they are fainthearted and irresolute. Everything that is vigorous, firm, and discreet will meet with my approval.” I suppose the general wasn’t “discreet” enough and therefore had to take the fall.

Col. Kenneth L. Weber,

USAF (Ret.)

Borden, Ind.

February 2007 , Vol. 90, No. 2

Tape recordings from the Nixon White House shed new light on an old controversy.

Lavelle, Nixon, and the White House Tapes

By Aloysius Casey and Patrick Casey

Air Force General John D. Lavelle in July 1971 assumed command of all air operations in Vietnam. He was known in the Air Force as an honest, hard-working, and capable leader. Seven months later, however, Lavelle would be fired as a result of allegations that he had ordered bombing missions into North Vietnam which were never authorized. Congressional hearings arising from his case raised serious questions of encroachment by the military upon the principle of civil authority. Lavelle denied the allegations until his death in 1979.

The case was complicated, a fact made clear by John T. Correll’s expertly told article, “Lavelle,” published in the November 2006 issue of this magazine. However, not all of the facts were known until now.

Hard evidence, from an unimpeachable source, shows that Lavelle had unequivocal authorization from the highest civilian authority—President Richard Nixon—to conduct so-called “preplanned strikes” in North Vietnam in February and March 1972. Equally hard evidence shows that senior military officials had approved earlier strikes of the same nature.

These statements are based on recently released White House audio recordings of Oval Office conversations as well as formerly classified JCS message traffic. We came across these pieces of evidence while developing material for our book, Velocity: Speed With Direction, a biography of Gen. Jerome F. O’Malley, which will be published this summer by Air University Press.

The background of the Lavelle case is generally well-known. However, certain parts of it bear retelling.

The story begins with Lavelle’s arrival “in country.” At that time, the overall US military commander in South Vietnam was Army Gen. Creighton T. Abrams. Responsibility for the air war in turn was delegated to Lavelle, who commanded 7th Air Force. Lavelle had operational control of USAF aircraft, control which was implemented by Major General Alton D. Slay, his operations officer. Slay issued orders to wings, including the 432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing, led by Colonel Charles A. Gabriel and his vice commander, Colonel Jerome F. O’Malley.

Lavelle inherited strange rules of engagement. In 1968, Washington suspended bombing in North Vietnam to induce Hanoi to talk peace. When he came to the White House in 1969, Nixon kept the policy, but USAF continued intensive airborne reconnaissance of the North, and fighter escorts were assigned. The rules of engagement in late 1971 (and early 1972) prohibited US warplanes from firing at targets in North Vietnam unless US aircraft were either (1) fired at or (2) activated against by enemy radar. In those cases, the escorts could carry out so-called “protective reaction” strikes.

In 1968, North Vietnam’s surface-to-air missiles were controlled by radar with a high-pulse recurring frequency, which keyed an alarm in the USAF aircraft. By late 1971, however, Hanoi had learned to “net” its long-range search radars with the missile sites. These additional sources of radar data allowed North Vietnam to turn on SAM radar at the last second, giving US crews virtually no warning.

Combat commanders believed it vital to let US aircraft defend themselves by attacking SAM sites and MiG airfields rather than waiting for a SAM site to launch a missile or a MiG to attack. Communiqués from Abrams to the JCS in Washington sought authority to destroy the MiG threat and recommended immediate strikes on Bai Thuong, Quan Lang, and Vinh airfields.

The JCS denied these requests, but urged commanders to make maximum use of authority allowable under existing ROE.

On November 8, 1971, Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, the JCS Chairman, arrived in Vietnam and personally approved a request from Lavelle to attack the MiG airfield at Dong Hoi. Moorer even reviewed the bomb damage assessment results that day, before departing Vietnam. Mission results also went to the Pentagon. Instead of questioning the mission, the JCS only suggested more careful planning.

The situation continued to grow more dire. In a top secret November 12 message to Moorer, Admiral John S. McCain Jr., head of US Pacific Command, warned, “I am deeply concerned over the mounting threat that the enemy’s integrated air defense network has posed against the B-52 force,” adding his conviction that “the enemy is more determined than ever to shoot down a B-52.”

On November 21, McCain sent another top-secret communiqué to Moorer, redoubling his effort to obtain more authority to bomb North Vietnamese targets. McCain made specific reference to the preplanned strikes previously authorized by Moorer himself. Moorer, in a top secret November 28 response, sounded understanding, but the Pentagon still declined to grant additional authority.

Another top official, Secretary of Defense Melvin R. Laird, visited the theater later in December. Lavelle met privately with the Pentagon chief in Saigon. At this meeting, Lavelle later asserted, Laird “told me I should make a liberal interpretation of the rules of engagement in the field and not come to Washington and ask him, under the political climate, to come out with an interpretation; I should make them in the field and he would back me up.”

Lavelle said he conveyed this information to Abrams, and “General Abrams said he agreed with Secretary Laird.”

By December 1971, US military forces had strong evidence that North Vietnam was preparing a massive conventional attack on the South. Combat losses heightened Lavelle’s concern about the operating rules and the effect on his crews. On Dec. 18, the 432nd lost three aircraft to enemy action, two to ground fire and one to MiG attack.

Early in 1972, a strike into North Vietnam raised anew the issue of authority for preplanned protective reaction strikes. A ground control intercept radar at Moc Chau, used to control MiGs, was a major threat as it provided current information on slow-moving US gunships. Abrams personally authorized a preplanned strike. US aircraft on Jan. 5 hit and disabled the Moc Chau site.

When informed, the JCS took a dim view of the Moc Chau raid. The Chiefs, in a message to US commanders, conceded “the logic” of the attack. “However,” they continued, “we are constrained by the specific operating authorities as written.”

US aircraft losses continued to mount. On January 17, 1972, the enemy hit two AC-130 gunships, with much loss of life. Three days later, the 432nd TRW lost an RF-4C fighter. Accordingly, Lavelle on January 23 ordered another preplanned protective reaction strike, this one against Dong Hoi airfield.

The strike was successful, but a miscue within the 7th Air Force headquarters command post caused a major misunderstanding. On his return flight, the USAF pilot radioed a report: “Expended all ordnance, the mission was successful, no enemy reaction.”

Lavelle, knowing enemy “reaction” was needed to justify every strike against targets in the North, snapped at his director of operations, Slay: “We can’t report ‘no reaction.'” The attacking pilot, Lavelle told Slay, “must report reaction.”

Lavelle later contended he meant that a pilot should report “hostile radar” as the enemy reaction, and that he earnestly believed that recording “hostile radar” complied with the ROE, since the netted enemy radar constituted an automatic “activation against” US aircraft. However, Lavelle went on to say that he did not take care to explain this to Slay.

Nor did Lavelle realize that the format of the official operations report for a mission would not permit the simple entry of the term “hostile radar” or “hostile reaction” without supporting details.

Slay told Gabriel and O’Malley, “You must assume by General Lavelle’s direction that you have reaction.” At subsequent preflight briefings, crews were told to record enemy “reaction,” whether or not it happened. While most of the missions caused real reaction—SAM, triple-A, or MiG fire—a few did not. On those occasions, crews reported “hostile enemy fire” anyway.

Eventually, this caused trouble. On January 25, 1972, Sergeant Lonnie D. Franks, an airman in the intelligence division of the 432nd TRW, was tasked to debrief crew members returning from a mission. He routinely asked whether they had received hostile fire. The crew responded, “No, we didn’t, but we have to report that we did.” Franks objected, but two superiors told him he was under orders to report enemy reaction.

Franks, troubled by this, reported the incident to Senator Harold E. Hughes (D-Iowa). This would produce military inquiries, Congressional hearings, and the sacking of Lavelle. In time, everything would become public.

Unbeknownst at the time, however, the issue of granting additional strike authority was being discussed at the highest levels of the US government.

The first such discussion began promptly at 10:53 on the morning of February 3, 1972, in the White House. President Nixon and Henry A. Kissinger, his national security advisor, sat down in the Oval Office with Ambassador Ellsworth F. Bunker, the US envoy to Saigon. By virtue of the setup of the military assistance command in Vietnam, Bunker was in overall charge of all American operations in Vietnam.

Bunker was in Washington for a hearing on his renomination as ambassador. At this particular meeting, though, he spoke on behalf of Abrams, who was seeking greater air strike authority.

Bunker began, “If we could get authority to, to bomb these SAM sites … Now the authority is for bombing when, when they fire at aircraft,” or “when the radars locked on. The problem is, that that’s, that’s late to start attacking.”

Kissinger chimed in, evidently supporting a more aggressive stance. He suggested that Nixon authorize US forces to strike any North Vietnamese SAM that had ever targeted a US aircraft.

He urged Nixon to “say Abrams can hit any SAM site that has locked on, even if it is no longer locked on.”

A lengthy discussion ensued. Finally, Nixon instructed Bunker to deliver to Abrams the following order:

“He [Abrams] is to call all of these things ‘protective reaction.’ Just call it protective reaction. All right? … I am simply saying that we expand the definition of protective reaction to mean preventive reaction, to mean preventive reaction where a SAM site is concerned. … Just call it ordinary protective reaction.” Then the President added, “Who knows or would say they didn’t fire?”

Kissinger, no doubt aware that any leak of such an ROE change could cause an uproar in Congress and the public at large, wanted to keep it a secret. He asked Bunker, “Now, could they stop from blabbing it at every bloody briefing?”

Nixon also wanted secrecy, for a specific reason. He was only weeks away from his historic February 21-28 visit to China, and he didn’t want a last-minute flare-up snarling his plan. This was clear from the context of his next comment.

Nixon told Bunker: “I want you to tell Abrams when you get back that he is to tell the military not to put out extensive briefings with regard to our military activities from now on—until we get back from China.”

Then Nixon went to some length to describe the new military dispensation.