EWELL, JULIAN J.

Headquarters, XVIII Airborne Corps, General Orders No. 19 (March 14, 1945)

Citation:

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Julian J. Ewell (0-21791), Lieutenant Colonel (Infantry), U.S. Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving as Commanding Officer, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, in action against enemy forces on the night of 18-19 December 1944, at Bastogne, Belgium.

In the darkness of 18-19 December 1944, Colonel Ewell’s regiment was the first unit of the 101st Airborne Division to reach the vicinity of Bastogne, Belgium, then under attack by strong enemy forces. While his regiment assembled, Lieutenant Colonel Ewell went forward alone to Bastogne to obtain first hand enemy information. During the night of 18-19 December 1944, Lieutenant Colonel Ewell made a personal reconnaissance amid intermingled friendly and hostile troops and on 19 December, by his heroic and fearless leadership of his troops, contributed materially to the defeat of enemy efforts to prostrate Bastogne.

On 3 January 1945, when an enemy attack threatened to blunt the impetus of the regimental offensive, Lieutenant Colonel Ewell personally lead a counterattack which stopped the enemy and made possible the continued offensive action of his regiment.

Throughout the action at Bastogne, the heroic and fearless personal leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Ewell were a source of inspiration to the troops he commanded. His intrepid actions, personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, the 101st Airborne Division, and the United States Army.

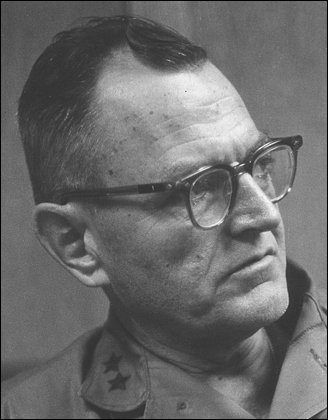

Lieutenant General Julian J. Ewell

Led Controversial Offensive in Vietnam

Julian J. Ewell, 93, a retired Army Lieutenant General who was a highly decorated paratrooper in World War II and who oversaw a major combat operation in Vietnam that critics inside and outside the military said killed thousands of civilians, died of pneumonia July 27 at Inova Fairfax Hospital. He lived at The Fairfax retirement community at Fort Belvoir, Virginia.

General Ewell held two top command positions in Vietnam, as commander of the 9th Infantry Division in the Mekong Delta and later as commander of II Field Force, the largest Army combat command in Vietnam.

Under his command between December 1968 and May 1969, the 9th Infantry Division launched a large-scale offensive, Operation Speedy Express, that aimed to quickly eliminate enemy troops with overwhelming force. The division claimed that 10,899 enemies were killed during the operation, but only 748 weapons were seized — a disparity, investigators said, that could indicate that not all the dead were combatants.

The Army Inspector General wrote in 1972, “While there appears to be no means of determining the precise number of civilian casualties incurred by U.S. forces during Operation Speedy Express, it would appear that the extent of these casualties was indeed substantial, and that a fairly solid case can be constructed to show that civilian casualties may have amounted to several thousand (between 5,000 and 7,000).”

That report was recently revealed by journalists Deborah Nelson and Nick Turse, who reported in 2008 that the vast scale of civilian deaths was the equivalent of “a My Lai a month.” My Lai, the massacre of nearly 500 Vietnamese by American troops in 1968, had scandalized the nation, deeply embarrassed the Army and undercut support for the war.

Turse described General Ewell’s Delta operation in a December article in the Nation magazine. In her book, “The War Behind Me” (2008), Nelson noted that after the operation ended and Gen. Ewell was at II Field Force, he “took notice of the civilian killings” and issued an order that such deaths would not be tolerated.

“From my research, the bulk of the evidence suggests that Julian Ewell presided over an atrocity of astonishing proportions,” Turse said in an interview Tuesday. “The Army had a lot of indications that something extremely dark went on down in the Delta from a variety of sources,” but it opted not to vigorously pursue the allegations.

Nevertheless, the 2008 revelations were not the first indication of trouble in the operation. A sergeant serving under General Ewell sent a series of anonymous letters to top Army commanders in 1970 about the high number of civilian deaths. Newsweek magazine investigated and published a truncated report. A Washington Monthly article gave an eyewitness account of helicopter gunships strafing water buffalo and children in the Delta.

Soldiers spoke out against the deaths, some in a congressional hearing, and Colonel David Hackworth, who served in the division, wrote in a 2001 newspaper column, “My division in the Delta, the 9th, reported killing more than 20,000 Viet Cong in 1968 and 1969, yet less than 2,000 weapons were found on the ‘enemy’ dead. How much of the ‘body count’ consisted of civilians?”

General Ewell was known in Vietnam for his attention to the enemy “body count,” considered an indication of success in the war. Subordinates noted that he never ordered them to kill civilians but was insistent about increasing the body count.

In an interview Tuesday, Ira Hunt, a retired Major General who was General Ewell’s Chief of Staff in the 9th Infantry Division, called him a “tremendous tactician and innovator.” By training large numbers of soldiers to be snipers, Hunt said, “We took the night away from the enemy. . . . They just totally unraveled in the Delta. He got the idea of putting night vision devices on helicopters, and we stopped the infiltration.”

General Ewell had the support of his superiors, as well. When he was promoted to command the II Field Force, General Creighton Abrams called General Ewell a “brilliant and sensitive commander . . . and he plays hard.” Critics of General Ewell’s command, Hunt said Tuesday, were engaging in “sour grapes.”

General Ewell’s 1995 book with Hunt, “Sharpening the Combat Edge,” said, “The 9th Infantry Division and II Field Force, Vietnam, have been criticized on the grounds that ‘their obsession with body count’ was either basically wrong or else led to undesirable practices.”

The charge was not true, they wrote, and General Ewell’s approach, “which emphasized maximum damage to the enemy, ended up by ‘unbrutalizing’ the war, so far as the South Vietnamese people and our own forces were concerned. The Communists took a different view, as could be expected.”

After Vietnam, General Ewell became military adviser to the U.S.-Vietnam delegation at the Paris peace talks. He retired in 1973 as Chief of Staff at the NATO Southern Command in Naples.

Julian Johnson Ewell was born November 5, 1915, in Stillwater, Oklahoma. He attended Duke University for two years before entering the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, graduating in 1939. He became a paratrooper in World War II.

Before dawn on D-Day, he jumped into Normandy with the 101st Airborne Division. So many paratroopers missed their landing zones that then-Lieuenant Colonel Ewell found only 40 of the 600 men in his battalion, but they managed to regroup and engage the Germans. In fall 1944, he parachuted into Holland, fighting in the defense of the Belgian city of Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army’s second-highest honor, for holding off two German divisions.

In 1952, he was sent to Korea as commander of an infantry regiment. He later spent four years at West Point, rising to Assistant Commandant of cadets. He became Executive Assistant to Presidential Military Aide General Maxwell Taylor at the Kennedy White House. He later served as Executive to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon and as Chief of Staff at V Corps in Germany before he went to Vietnam in 1968.

His other military awards included four awards of the Distinguished Service Medal, two awards of the Silver Star, two awards of the Legion of Merit, the Bronze Star Medal, the Purple Heart and the Air Medal.

His marriages to Mary Gillem Ewell and Jean Hoffman Ewell ended in divorce. His wife of 40 years, Beverly McGammon Moses Ewell, died in 1995. In 2005, he married retired U.S. ambassador to Madagascar Patricia Gates Lynch Ewell, in a ceremony performed at the U.S. Supreme Court offices of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

Survivors, in addition to his wife, include a son from his first marriage, Gillem Ewell of Charles Town, West Virginia; a daughter from his second marriage, Dorothy Ziegler of Montgomery, Alabama; twins from his third marriage, Dale Moses Walker of Albuquerque and Stephen Moses of Williamsburg; two stepchildren, Pamela Gates Belanger of Denver and Lawrence Alan Gates of Memphis; six grandchildren; and a great-granddaughter.

JULIAN JOHNSON EWELL, Lieutenant General, United States Army (Retired.)

On Monday, July 27, 2009, Julian J. Ewell age 93 of Fairfax, Virginia. Born in Stillwater, Oklahoma. Graduated from the United States Military Academy, West Point Class of 1939. Jumped into Normandy before dawn June 6, 1944, with the 101st Airborne Division. Received the Distinguished Service Cross for his leadership and heroism at the Battle of Bastogne. Commanded the 9th Infantry “Manchu” Regiment of the 8th Army during the Korean War. Was the Assistant Commandant of Cadets at West Point. He commanded the 9th Infantry Division followed by command of the II Field Force, Vietnam and subsequently served as the military advisor to the Paris Peace delegation. Completed his service as Chief of Staff, NATO Southern Command at Naples, Italy.

A highly decorated veteran his honors include four Distinguished Service Medals, Two Silver Stars, a Bronze Star, Purple Heart, Air Medal, Combat Infantry Badge, Two Legion of Merits, and many foreign decorations including the French Legion of Honor-Chevalier.

Throughout his career General Ewell was known for his leadership style, keen intellect, droll wit and devotion to his country, his men and his profession. Marriages to Mary Gillem and Jean Hoffman ended in divorce. A 40-year marriage to Beverly McGammon Moses ended with her death in 1995. In 2005 he married Ambassador Patricia Gates Lynch.

General Ewell is survived by four children: Gillem Ewell of Charles Town, West Virginia, Dorothy Ziegler of Montgomery, Alabama, Dale Moses Walker of Albuquerque, New Mexico, Stephen Moses of Williamsburg, Virginia. Two stepchildren Pamela Gates of Denver, Colorado and Lawrence Gates of Memphis, Tennessee, six grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Services will be held at The Old Chapel, Fort Myer, Virginia, 11 a.m. Tuesday October 27, 2009, followed by burial with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. In lieu of flowers the family requests that donations be made to Army Emergency Relief, 200 Stovall St., Alexandria, Virginia 22332-0600. Services will be held at The Old Chapel, Fort Myer, Virginia, 11 a.m. Tuesday October 27, 2009, followed by burial with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. In lieu of flowers the family requests that donations be made to Army Emergency Relief, 200 Stovall Street, Alexandria, Virginia 22332-0600.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard