One of first Naval aviators died at the St. Albans Naval Hospital in Queens, New York, April 30, 1955. He had lived at 161 East 79th St, and was 70 years old. Told friends that wanted any obituaries written about him to say, with no evasions, that he died of cancer.

His career was dogged battle to win acceptance for airplane from a Navy that, during most of his years of service, dominated by battleship admirals. One of the most spectacular incidents of his career was 1919 flight of three NC Navy planes that took off from Newfoundland and sought to cross Atlantic. Then-Commander Towers, forced to land his plane in rough seas, taxied craft 205 miles to Azores. A second crew also was forced down. But the NC-4 reached the Azores and then flew on to Portugal and England to become first plane to cross Atlantic. The expedition, for which he had been instrumental, proved a signal triumph for Navy’s air-minded minority.

He was buried in Section 30 (Grave 676) of Arlington National Cemetery along with his wife, Pierrette Anne Towers (1902-1990).

National Aviation Hall of Fame

TOWERS, JOHN HENRY – 1966

A native of Rome, Georgia, Towers was graduated by the United States Naval Academy in 1906 and then went to sea, serving with distinction aboard the battleship Kentucky.

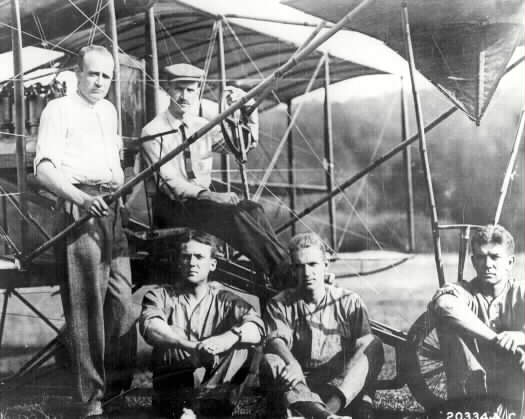

He became interested in aviation and after numerous requests for aviation duty he was finally granted his wish and assigned to the Curtiss Flying School on June 27, 1911. There he became the Navy’s third aviator following Theodore Gordon Ellyson and John Rodgers. He learned to fly the Navy’s first airplane, a Curtiss seaplane called the A-1.

It was soon afterward that he and Ellyson made a record distance flight down the Chesapeake Bay from Annapolis to Old Point Comfort, Virginia, in the A-1. Later, he took over the training of the other young Navy pilots. One of the highlights of 1912 occurred in October when he rigged extra gasoline tanks to a Curtiss seaplane for an endurance flight. Taking off from the Severn River at Annapolis early in the morning, he climbed up over the Chesapeake Bay and remained aloft over 6 hours, setting a world’s endurance record the first official record flight made by a Naval pilot.

Early in December he completed tests which demonstrated the ability to spot submarines from the air, even in the muddy waters of the Chesapeake Bay. In 1913 he was in charge of the aviation unit which began its first operations with the Fleet off Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. He and his follow Navy pilots explored all the potential of their planes to serve the Navy aerial reconnaissance, bombing, aerial photography, and wireless communications. In the ocean waters off Cuba they were able to spot submarines at depths of 30 to 40 feet.

One day in June, 1913, he was a passenger in the Wright seaplane being piloted by Ensign William Billingsley. Suddenly, 1,600 feet above Chesapeake Bay, they hit severe turbulence. Without warnings Billingsley was hurled out of the seat and fell to his death on the water far below. The first Navy pilot to make the supreme sacrifice. Unbelievably, Towers managed to catch and cling to a wing strut and ride the plummeting unpiloted plane down, miraculously surviving the crash. After that incident, he ordered safety belts for all the Navy planes.

In January 1914 he set up the first training Naval Air Station in an abandoned Navy yard at Pensacola, Florida. It was from here that he led his unit in the first Naval air operations during the Mexican crisis. It was after World War I that he participated in one of the greatest exploits in aviation history. It was in 1919 that he led the Navy’s attempted trans-Atlantic flight of Curtiss NC flying boats. All four planes were ready in April for the departure from Rockaway Naval Air Station, but a severe storm scratched the NC-2 from the flight. When they took off on May 8th on the historic flight, he was in command of the flight and of the Flagship W-3. Patrick Bellinger commanded the NC-1 and Albert C. Read the NC-4.

The first leg of the flight was to Halifax, but the NC-4, suffering severe engine troubles was forced to land at sea. The NC-1 and NC-3 proceeded from Halifax on to Trepassay, New Foundland, and awaited there until the NC-4 arrived after being repaired. On May 16 all three planes were ready and took off from Trepassey’s harbor. Out over the sea, the planes climbed to 1,000 feet an occasional iceberg glinted in the light of the setting sun. It was planned to fly in formation but both his NC-3 and Bellinger’s NC-1 fell behind Read’s NC-4 as night fell. By early morning they encountered heavy weather. Churning through rain squalls and fog, his NC-3 became hopelessly lost and he had to set her down on the storm-tossed ocean. Unable to take off again because of buckled wing struts, he turned to his experience as a seaman. Rigging a canvas bucket for a sea anchors he used the plane’s rudder to drift sail toward Sao Miguel Island, 200 miles away. It was an almost impossible task for an experienced seaman with a reliable ship, but fifty-two grueling hours later he and his crew triumphantly taxied their battered ship into harbor in the Azores an the crowd lining the shore went wild with their joy-ous welcome. Nine days later the NC-4 flew on to Lisbon to complete the historic first trans-Atlantic flight. It was a triumph of planning and skillful flying by the Naval aviators.

But perhaps his greatest contribution was his vision in 1921, when he began training of Navy pilots in land planes, in his anticipation of the requirements of the Navy’s aircraft carriers yet to come. In 1922 the Navy converted a Collier into the Langley, the first aircraft carriers and the practical problems of operating aircraft from it were gradually solved. Arresting gear and barricades were developed to provide safety in landings. The carriers Lexington and Saratoga were also authorized and these three ships eventually became the nucleus of our pre-war carrier fleet. He served as Executive Officer and later Commander of the Langley and also later of the Saratoga.

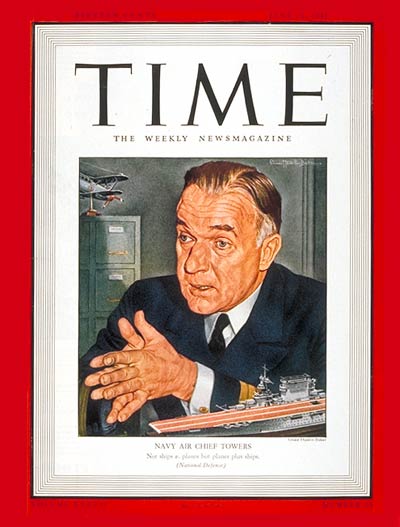

Finally, in June, 1939, he became Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, with the rank of Admiral, becoming the first pioneer Naval aviator to achieve flag rank, and was responsible for expanding Naval aviation in these days of ever-changing criteria.

When the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor, Naval aviation was just 30 years old and the Navy faced the greatest task in its history for many of its warships and airplanes lay in the mud of Pearl Harbor. But dedicated pioneer Naval aviators such as he were the Navy’s greatest asset, for they had lived and breathed flying ever since our first carriers were launched. They were able to pass their lessons on to the thousands of Naval aviators to be trained. He directed Naval aviation’s expansion during World War II and helped develop the strategy for winning the war in the Pacific.

By 1943 a tremendous change was wrought in the Pacific as the “Flat-Top” became “Queen” of the fleet and its aircraft led the fleet toward victory an the world’s greatest sea-borne Air Force.

At the end of the war, he commanded the second Carrier Task Force, Task Force 38, and the Fifth Fleet. He then served as the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet and finally as Chief of the Navy’s General Board. In 1947 he ended a long and distinguished 41-year career in Naval aviation and he passed on in 1955.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard