Jacob Hurd Smith of Ohio

- Appointed from Illinois, First Lieutenant, 2nd Kentucky Infantry, 5 June 1861

- Captain, 28 January1862

- Honorably mustered out 29 June 1863

- Captain, Volunteer Reserve Corps, 25 June1863

- Honorably mustered out 21 October 1865

- Captain, 13th U. S. Infantry, 7 March 1867

- Unassigned, 25 May 1869

- Major, Judge Advocate, 25 May 1869

- Appointment of Major, Judge Advocate, Revoked 10 December 1869

- Assigned to 19th U. S. Infantry, 15 December 1870

- Major, 2nd U. S. Infantry, 26 November 1894

- Lieuenant Colonel, 17th U. S. Infantry, 30 June 1898

- Colonel, 17th U. S. Infantry, 20 October 1899

- Brigadier General, U. S. Volunteers, 1 June 1900

- Brigadier General, U. S. Army, 30 March 1901

- Breveted Major, 7 March 1867, for gallant conduct in the battle of Shiloh, Tennessee, 6 April 1862

- Retired 16 July 1902

Remaining in the Far East for a short time more, Waller led a detachment of marines which defeated Philippine insurgents in a battle at Sohoton cliffs on 5 November 1901. Later, he led an expedition across the island of Samar, from 28 December 1901 to 6 January 1902—subduing Moro insurgents under great climatic hardships—his battalion returning to Cavite on 2 March.

When Major Littleton Waller arrived in the Philippines he had this conversation with his superior, Brigadier General Jacob H. Smith:

“I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and burn the better it will please me. I want all persons killed who are capable of bearing arms in actual hostilities against the United States.” General Jacob H. Smith said.

Since it was a popular belief among the Americans serving in the Philippines that native males were born with bolos in their hands, Major Littleton “Tony” Waller asked “I would like to know the limit of age to respect, sir?.”

“Ten years,” Smith said.

“Persons of ten years and older are those designated as being capable of bearing arms?”

“Yes.” Smith confirmed his instructions a second time.

Waller executed eleven Filipino guides without trial. The ten natives were shot in groups of three (one had been gunned down in the water attempting to make a run for it)…The bodies were left in the square as an example until one evening, under cover of darkeness, some townspeople carried them off for a Christian burial.

Waller reported the executions to Smith, as he had faithfully reported every other event. “It became necessary to expend eleven prisoners. Ten who were implicated in the attack on Lieutenant Williams and one who plotted against me.” Smith passed Waller’s report to General Adna Chaffee. For some reason Chaffee decided to investigate these executions, despite J. Franklin Bell and Colonel Jacob Smith carrying out similar executions on a much larger scale months before with no subsequent investigations. Possbily Chaffee realized the increasingly negative political climate back home.

Waller’s outfit on Samar was relieved by Army units on February 26, 1902.

Waller was tried for ordering the execution of eleven Filipino guides and tried for murder. A court martial began on March 17, 1902.

Waller did not used Smith’s orders “I want all persons killed” to justify his deed, instead relying on the rules of war and provisions of a Civil War General Order 100 that authorized exceeding force, much as J. Franklin Bell had successfully done months before. Waller’s counsel had rested his defense.

The prosecution then decided to call Smith as a rebuttal witness. Smith was not above selling out Waller to save his career. On April 7, 1902, Smith perjured himself again by denying that he had given any special verbal orders to Waller.

Waller then produced three officers who corroborated Waller’s version of the Smith-Waller conversation, and copies of every written order he had received from Smith, Waller informed the court he had been directed to take no prisoners and to kill every male Filipino over 10.

During the trial, newspapers back home, including his newspaper in Philadelphia, nicknamed Waller the “Butcher of Samar”.[

Waller was acquitted. Smith was admonished and was forced into retirement.

General Jacob Hurd Smith (1840-March 1, 1918) was a veteran of the Wounded Knee massacre and well known among Indian campaigners.

Jacob Hurd Smith is infamous for an incident in the earlier part of the Philippine-American war, he served as a Colonel under General J. Franklin Bell in Batangas. After the Balangiga Massacre, General Adna Chaffee promoted Smith to Brigadier General and put him in charge of the Samar campaign. In Samar, Smith earned fame with his orders to “kill everyone over the age of ten” and make the island “a howling wilderness.”

General Jacob H. Smith’s infamous order “KILL EVERYONE OVER TEN” was the caption in the New York Journal cartoon on May 5, 1902. The Old Glory draped an American shield on which a vulture replaced the bald eagle. The bottom caption exclaimed, “Criminals Because They Were Born Ten Years Before We Took the Philippines.””I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and burn the better it will please me. I want all persons killed who are capable of bearing arms in actual hostilities against the United States.” General Jacob H. Smith said.

Since it was a popular belief among the Americans serving in the Philippines that native males were born with bolos in their hands, Major Littleton “Tony” Waller asked “I would like to know the limit of age to respect, sir?.”

“Ten years,” Smith said.

“Persons of ten years and older are those designated as being capable of bearing arms?”

“Yes.” Smith confirmed his instructions a second time.

He was dubbed “Hell Roaring Jake” Smith, “The Monster”, and “Howling Jake” by the newspapers.

In May of 1902, Smith faced court-martial for his orders, being tried not for murder but for “conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline”. In other words, he was tried for a verbal gaffee. The court-martial found Smith guilty and sentenced him “to be admonished by the reviewing authority.” In other words, verbally reprimanded.

To ease public outcry Secretary of War Elihu Root recommended that Smith be retired. President Theodore Roosevelt accepted this recommendation, and ordered Smith’s retirement, with no additional punishment.

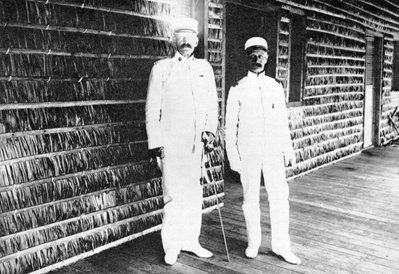

General Smith Tacloban, Philippines, 1901

By the 1902 court-martial, Smith had been wounded in battle three times:

Smith had a scar from a saber cut on the head that he had received in July 1861 in Barboursville, Virginia. Since April 7, 1862 he had been carrying a Minie ball from the Civil War Battle of Shiloh in his hip. Smith also had lead in his body from a wound at El Caney Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

Smith was disabled in the Civil War Battle of Shiloh on April 7, 1862. He tried to return to duty that summer, but the wound would not heal properly, so he became a member of the Invalid Corps, serving out the remainder of the Civil War as a mustering officer/recruiter in Louisville for three years. His service record states that he was good at recruiting colored troops.

While working in Louisville he met and later married Emma L. Havrety in November 1864.

In 1869 Smith’s father-in-law, Daniel Havrety claimed bankruptcy. The lawyers for the bankruptcy court noticed a tremendous enlargement of Jacob Smith’s assets while in Louisville, from $4,000 in 1862 to $40,000 in 1895. Smith admitted that he was involved in a brokerage scheme using bounty money for army recruits to finance a side business and speculations in whisky, gold, and diamonds. Smith said he receipted for a package sent via Express from New Orleans to Cleveland. The package came from his father in law and was addressed to Smith’s mother-in-law. Smith later learned the package contained $13,000 dollars.

Army judge advocate position

In 1869 Smith was trying to get a temporary army judge advocate position converted into a permanent position. One of the parties in the bankruptcy case, John McClain, informed the Senate Committee on Military Affairs about Smith’s bounty brokerage scheme.

Smith wrapped himself in the flag and argued to the committee that he had been in seven engagements and had been wounded in the Battle of Shiloh, and referring to himself said: “One who took upon himself all the odium that the rebels and conservatives of Louisville, Kentucky, heaped upon him, by being the first officer, to my knowledge, who commenced mustering into service the colored man in Kentucky during the year 1863.” Smith said that he had scoured Kentucky’s prison pens, jails, and workhouses to find these men. He concluded that his only aim was to serve his God and his country properly. Smith admitted to speculating, but justified it by saying that others had made three times as much money as he had in Louisville during the war, and he had not defrauded anyone.

His military superiors did not accept this patriotic excuse. So Smith wrote a more apologetic explanation, painting himself as a gullible dupe. Everyone who could substantiate his story had either died or left the country. Smith had also conveniently destroyed or lost all of his own bank account records for that period. Smith insisted he had not cheated any of the colored recruits out of their $300 bounty money/enlistment bonus.

Military officials did not believe Smith. Smith’s temporary appointment as judge advocate was revoked by the President and it was recommended by Joseph Holt that the entire file of papers be sent to the Senate Committee. Holt mentioned by Smith’s own testimony how Smith felt it was alright to mislead and deceive military auditors. “By his conflicting statements and his unfortunate explanation, he is placed in a dilemma full of embarrassment.”

Smith’s future gaffes

Smith’s subsequent history was to prove that he had a penchant for emitting imprudent remarks both written and oral.

An 1867 efficiency report described him as “garrulous”. (Given to excessive and often trivial or rambling talk; tiresomely talkative.)

In 1877 Smith responded to a written reprimand from his Colonel with a disrespectful longhand response. Technically the Colonel could not censure Jacob Smith because he had been released from his command because of the incident that was being investigated. When Jacob’s company was marching away, the Colonel indicated his displeasure. Smith’s reply made fun of the colonel. Saying he was like Prussian General von Moltke, Smith said the colonel’s rebuke was like an “Irishman who was remonstrated with for letting his wife whip him, and answered, ‘It is fun for her, and don’t hurt me”. The Colonel notified Smith there would be a court-martial, and so Smith wrote the Colonel a nasty letter. Smith was not court-martialed, and instead Major John Pope lectured Smith and recommended the whole affair be dropped since Smith had apologized.

Brigadier General Jacob Smith with Major General Adna R. Chaffee Tacoblan, Leyte, 1902

Legal problems

During the 1870s Smith was called away from duty for several lawsuits for debt. One case dragged on in a Chicago court from 1869 to 1883.

Another creditor named Henry continued a claim against Smith for $7 for payment of a harness. The case dragged on from 1871 to 1901. Henry even sent a letter to President McKinley about Smith and his $7 debt.

On July 31, 1884 Smith was sued again in Chicago by the legal firm Pedrick and Dawson.

Smith was court martialed in 1885 in San Antonio for “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman, for deeds in the “Mint Saloon” in Brackett Texas. The opposing party claimed Smith had been playing a game of draw poker with M.S. Moore and C.H. Holzy A.K.A. Jiggerty, lost $135 to Moore, and welshed on the debt. Smith was found guilty and was confined to Fort Clark for a year and forfeited half his pay for the same time period. The Reviewing Authority thought the court was too lenient on Smith. It also felt that Smith’s courtroom tactics made a mockery of the legal procedure:

demanding witnesses from distant and impractical locations especially since he never actually used the witnesses in court, local civilian witnesses for some reason were intimidated so they refused to testify against Smith, local civilian witnesses for the defense selectively decided which questions they would answer and which they would not. While the draw poker case was pending in 1885, Smith wrote a letter to the Adjutant General of the Army. The letter was regarding the case and the Adjutant found out that many of the statements were lies. Because of this, Smith was tried again in 1886 and was found guilty, and would have thrown him out of the military. Smith was only saved by President Grover Cleveland who allowed Smith to return to the military with only a reprimand.

In 1891 Smith was charged with using enlisted men as his servants in his home.

Smith brags to media about war crimes

In December 1899, Colonel Jacob Smith infomed reporters in the Philippines that, because the natives were “worse than fighting indians”, he had already adopted appropriate tactics that he had learned fighting “savages” in the American west, without waiting for orders to do so from General Elwell S. Otis. This interview provoked a headline announcing that “Colonel Smith of 12th Orders All Insurgents Shot At Hand,” and the New York Times enthusiastically endorsed Smith’s lawlessness as “long overdue.”

Smith’s alleged war crimes, like those of J. Franklin Bell were not investigated.

William Howard Taft’s mistake

Because of Smith’s bravery in Cuba during the Spanish-American War William Howard Taft, who was the civilian governor of the Philippines, decided to promote Smith to Brigadier General with a caveat. Taft wrote, Smith “had reached a time when promotion to a Brigadier Generalship would worthily end his services, for I believe it is his intention to retire upon promotion.” Smith was promoted, but he decided not to retire.

Starting in the late 1880’s the Army had adopted the system of filling each brigadier general position not by qualifications, but by mere seniority. The system usually gave elderly colonels a few more months, weeks or days of active duty with a new title, followed by nearly immediate retirement at a higher pay rate. The problem with Jacob Smith was that he was slightly younger and his promotion to general was made too soon because he had three years left until retirement became mandatory by law.

Smith causes an uproar in Luzon

Spanish Friars were the principal cause of the Filipino revolution in Spain, and many friars had been massacred and tortured by the Filipino population. American foreign policy was to stay strictly neutral in religious matters.

In September 1900, while Smith was the military governor of Pangasinan, Tarlac, and Zambales, Smith intervened in a religious dispute in the village of Dagupan. Smith sided with a priest who was friendly with the friars. This caused an angry civilian uproar in central Luzon.

Waller’s court martial

A court martial began on March 17, 1902 of Major Littleton Waller, one of Smith’s subalterns (Lower in position or rank). Major Littleton Waller was being tried for ordering the execution of eleven Filipino guides.

Waller did not used Smith’s orders “I want all persons killed” to justify his deed, instead relying on the rules of war and provisions of a Civil War General Order 100 that authorized exceeding force, much as J. Franklin Bell had sucessfully done months before. Waller’s counsel had rested his defense.

The prosecution then decided to call Smith as a rebuttal witness. Smith was not above selling out Waller to save his career. On April 7, 1902, Smith perjured himself again by denying that he had given any special verbal orders to Waller.

Waller then produced three officers who corroborated Waller’s version of the Smith-Waller conversation, and copies of every written order he had recieved from Smith, Waller informed the court he had been directed to take no prisoners and to kill every male Filipino over 10. This is how the infamous order became public.

General Adna R. Chaffee, the Division Commander in the Philippines, cabled the War Department requesting permission to keep Smith in the islands for a short time, since he feared that Smith if given the opportunity to talk to reporters, could speak “absurdly unwise” and might say things contrary to the facts established in the case, or act like an unbalanced lunatic.

Later life

Smith retired to Portsmouth, Ohio, doing some world traveling. He volunteered his military services by letter to the Adjutant General’s Office on April 5, 1917 to fight in World War I. He died the next year in San Diego California, March 1, 1918.

- SMITH, JACOB H

- BG USA RET

- DATE OF DEATH: 03/01/1918

- BURIED AT: SECTION SW SITE 1924

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

- SMITH, ADELSIDE (ADELAIDE) W/O JACOB H

- DATE OF DEATH: 10/09/1940

- BURIED AT: SECTION SCH SITE 1924

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY - WIFE OF JH SMITH, BRIG GEN US ARMY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard