Courtesy of His Classmates

United States Military Academy Class of 1943

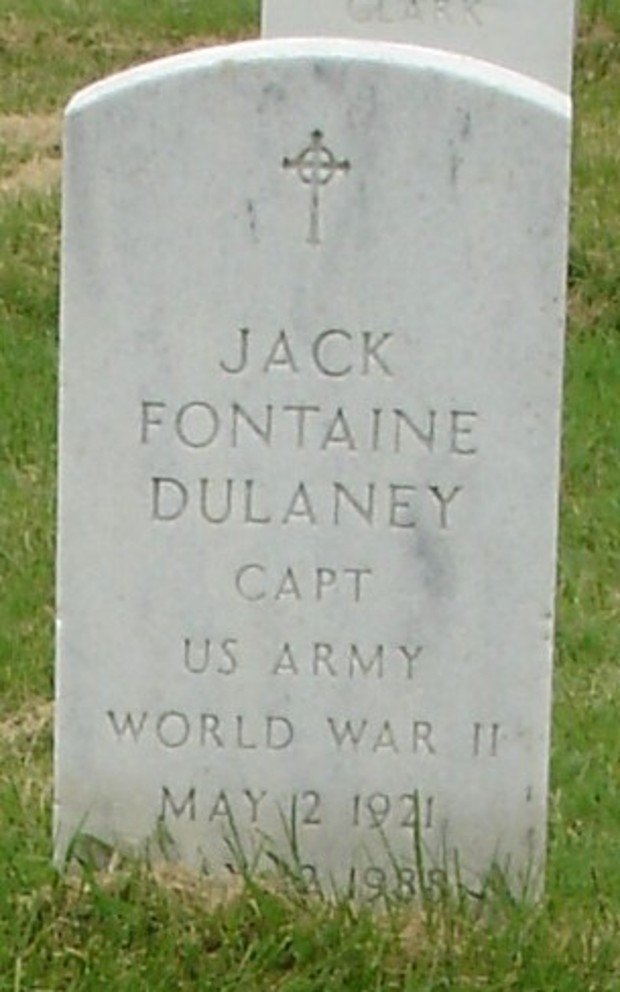

Jack Fontaine Dulaney

No. 13422 • 2 May 1921 – 12 May 1988

Died in Atlanta, Georgia, aged 67 years

Interment: Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia

JACK FONTAINE DULANEY was born in Ruleville, Mississippi, the son of Jack Fontaine and Eula Norwood Dulaney. On the death of his father, who died of wounds received in World War I, Jack and his mother moved to Greenville, Tennessee, where he grew up in the shadows of the Great Smoky Mountains. At an early age he knew he wanted to attend West Point and become a professional soldier. Jack’s mother, fondly known as “Baby,” made a decision that it would be prudent for him to attend Marion Military Institute in Alabama for a year after his graduation from Greenville High School.

That was a wise decision; Beast Barracks, and plebe year in general, posed no problems for this happy-go-lucky youth. In fact, if one can enjoy and absorb the best of plebe year, such was the case with Jack Dulaney. Early in Beast Barracks, Jack was affectionately named “Dopey” — a name which followed him for the remainder of his life. Staying “pro” in academics was a necessary evil that he accepted as a fact of life. With an absolute minimum of effort, he lived dangerously in the academic world of West Point.

Jack was a natural athlete — at or near the top of the class in all phases of physical training. As a member of the boxing team, competing as a light heavyweight, he never lost a match. He was East Coast Intercollegiate Champion for two years; early graduation prevented what would have been a probable third year as champion.

After graduation came Infantry School and Parachute School. His first and only assignment was to “I” Company, 3rd Battalion, 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division. Prior to the invasion of Europe there were maneuvers in Tennessee and special training in England. During the early hours of D-Day in 1944, Jack and his platoon executed a night jump inland from Omaha Beach, landing on the outskirts of Ste. Mere Eglise. Shortly after landing, Jack was hit in the upper left arm by sniper fire; he refused to be evacuated. Compresses were applied to the entrance and exit holes in his arm and he continued to march.

On day four of the invasion, his platoon was pinned down by machine gun fire from the far side of a hedgerow. On this particular day, his platoon was the assault echelon of the assault company of a major attack. The following is an exact quote from the acting platoon sergeant:

“The command came down from battalion to move out and destroy the machine guns. Lieutenant Dulaney picked up two extra grenades, ordered us not to follow him until he motioned us forward, and then ran towards the gun by bounds. About two-thirds of the way across the field he was hit and fell to the ground. Initially no attempt was made to assist him. Finally I dropped my pack and went after him. I was able to get to him, put him on my back, and crawl back to the shelter of the near hedgerow. However, while I was getting him back to cover, he was hit two or three more times.”

For this action Jack Dulaney was awarded the Silver Star for gallantry in action, and the Purple Heart with Oak Leaf Cluster.

As a result of his serious wounds, Jack spent three years in five different hospitals; during this time he underwent three operations. In 1947 he married Jerry Wolf, and in 1948 he was retired with 100% disability as a captain of Infantry.

Jack returned to college and earned an advanced degree in chemical engineering from the University of Tennessee. This was followed by a long and successful career with Allied Chemical and Dye Company. In the late 1970s, he left Allied Chemical for further success as an independent commodities broker. But in the mid-1980s, his wounds began to catch up with him, and he was forced to curtail his activities. His wounds had never completely healed. At the last, severe blood poisoning claimed his life.

So died a gallant soldier whose battlefield bravery in a small-unit action was to mark and affect the rest of his life. That he was able to overcome constant pain, gain a graduate degree, and contribute so much more to the nation is further manifestation of the qualities of a champion shown in the boxing ring and on a small field in Normandy. Let us hope our country will never forget what was needed on the battlefield to win the peace that Europe has enjoyed for 45 years.

He is survived by his wife, Jerry; by his three children, Thomas Ashton, Jack Fontaine, and Susan Elquist; and by his two grandchildren, Steve and Dawn Marie.

Not long after returning home, Jack Wheeler drove with parents to a funeral at Arlington National Cemetery. Big Jack’s (John Parsons Wheeler, Jr.) roommate from the United States Military Academy class of 1943.

Jack Fontaine Dulaney of Greenville, Tennessee – nicknamed Dopey – had died at age 67. A champion boxer at USMA, was known for custom of solicitously hugging his battered opponents after each bout. Winner of Silver Star and two Purple Hearts in Europe during WWII, Dopey Dulaney had been Jack’s godfather. Thirty classmates from ’43 gathered at the gravesite. Jack had heard familiar thacka-thacka-thacka of military helicopter skimming over the Potomac. The honor guard stood at rigid attention with ceremonial M-14s at the ready, the same weapon Jack had used during marksmanship training in Beast Barracks. I know that rifle, he thought, I know it the way I know my own hands.

Big Jack, his silver hair glinting in sunlight, spoke at grave. Although he had turned 70 years old, his command voice carried across the headstones with crisp authority of a young man. “Dopey and I,” he recalled, “met nearly 50 years ago in old E Co. It’s no secret that he and the academic departments had their ups and downs. But there’s one thing we all know about Dopey: he was one of the best soldiers in our class. He jumped into Normandy on D-Day. He was wounded and then, some days later, wounded again. His leg wound stayed with him all of his life. He married the nurse who tended his wounds. All these years, he has been an important part of our class fellowship.” Big Jack’s voice dropped to a raspy whisper. “He was a soldier’s soldier. God will keep him.”

The rifle squad fired three volleys. Jack scooped up two of ejected cartridges and slipped them into his pocket as keepsakes, one for himself and other for Big Jack. Yes, in the middle of his journey he was in a dark wood where the straight way was lost. But he would find his way again, because, simply, that was what West Pointers did. They embraced opponents after thrashing them senseless in boxing ring. They spoke, even as septuagenarians, with impassioned conviction about duty and honor and country. And when they were lost, they pushed on until they were found.

Someday Jack would speak at his father’s funeral. He had occasionally wondered what he would say when that day came. Now he knew precisely: “He was a soldier’s soldier. God will keep him.” Dry-eyed, fingering the brass cartridges in his pocket, Jack walked briskly from cemetery, leaving dead behind.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard