- Full Name: JAMES EDWIN PLOWMAN

- Date of Birth: 10/14/1943

- Date of Casualty: 3/24/1967

- Home of Record: PEBBLE BEACH, CALIFORNIA

- Branch of Service: NAVY

- Rank: LCDR

- Casualty Country: NORTH VIETNAM

- Casualty Province: NZ

- Status: MIA

Now He Knows What He Missed

Man Who Lost His Dad to Vietnam Will Bury Him Soon in Arlington

By Candace Rondeaux

Curtesy of the Washington Post

Sunday, June 18, 2006

For years, his father was nowhere and everywhere. He was tucked between the pages of the Hardy Boys novels he inherited from his dad. He was in his room, where he kept the display box of his father’s military medals. He was next to his model of the A-6A Intruder and in the black-and-white photo he keeps alongside those of his wife and three young children.

“I remember opening a utility drawer in the kitchen and finding this little class photo mixed in there with a bunch of other junk,” said James Plowman Jr., Loudoun County’s top prosecutor. “And I said to my mom, ‘I don’t remember this picture of me — when was it taken?’ She said, ‘That’s not you, that’s your father.’ ”

James Plowman Jr. regrets not being able to grow up with his father, who was killed in the Vietnam War.

As he prepares to bury his father’s reclaimed remains, he reflects on the lessons he learned in his father’s absence.

It was always like that; his father flashed through him at unexpected times. A tilt of the head. A smile. A gesture. A wisecrack Plowman would make would bring the memories flooding back to his relatives.

Some of what Plowman knows about his dad came home in a Navy footlocker years after his 23-year-old father was shot down in his A-6A Intruder in 1967 in Vietnam. There’s the snapshot of him on the deck of the USS Kitty Hawk, mugging rakishly for the camera. It was taken a few months before Plowman was born. There’s his father’s dress sword, the one his dad might have worn to another sailor’s funeral had he returned home alive.

But Lieutenant James E. Plowman Sr. is finally coming home. Military investigators found his crash site a couple of years ago and his remains are positively identified. He’ll be buried at Arlington National Cemetery this summer.

“I couldn’t believe it when they called and said they thought they had found the crash site. I said, ‘I can’t believe you’re even still looking,’ ” said Plowman, 38.

The Defense Department is, indeed, still searching — for 1,803 Americans lost in Vietnam and for 88,000 Americans still missing from other wars.

It has been nearly four decades since Plowman’s father was declared missing in action. Plowman used to say you can’t miss what you don’t know when people asked about his dad. But now that Plowman is a grown man with a family of his own in Leesburg, he’s finding out you can know what you missed.

‘Where Is My Father?’

In the early days, when Plowman was a boy, his family didn’t dare give up the search. Rumors and reports about his father were painfully persistent. First, an East German photographer took a picture of two men with a striking resemblance to Plowman’s father and the pilot who was with him, Captain John C. “Buzz” Ellison. Then two Americans who were released from a North Vietnam prison camp mentioned seeing Ellison.

The waiting seemed endless. Wives of the missing wrote letter after letter into the Hanoi void. Plowman’s mother, Kathy Super, was waiting, too. She was 22 and five months pregnant with him when she learned that her husband was missing. They had met when they were teenagers living with their families on a Navy base in Guam. The couple courted for about six years, then married 10 days before he shipped out to Vietnam.

It was James Plowman Sr.’s first tour of duty, but he was far from green. Before he and Ellison launched their March 24, 1967, attack on a thermal power plant near the Vietnam-China border, they had flown more than 80 missions. On the return home, they came under enemy fire and disappeared from radar about 11 p.m. Their plane went down near a village in Ha Bac Province in northern Vietnam.

Plowman’s mother became a symbol for the P.O.W./M.I.A. movement, organizing alongside other wives and families of the missing. They were a tightknit group with a mission to pressure Hanoi to release information about their husbands and sons. His mother, Plowman said, does not want to talk about those days now, having said everything there was to say about them.

Young, proud and alone, but for each other, the women told their stories to anyone who would listen. Reporters and photographers began showing up at Plowman’s house. They snapped melancholy photos of the boy without a father for Life magazine. He became the poster boy for the missing. He remembers a huge billboard showing him and another boy whose father was missing. “Where is my father?” the billboard asked.

‘I Want to Be There’

Kathy Super asked the Navy in 1973 to declare her husband killed in action. “It was a tough decision for her, but she wanted to set an example for the other wives,” said Plowman’s uncle, John Plowman, 59. “She needed to move on.”

Then, he said, “she decided to move out of her parents’ house when Little Jimmy started calling her father — his grandfather — ‘Dad.’ ”

Plowman says he doesn’t remember that. He doesn’t remember his uncle getting sick the night before the funeral service at Arlington National Cemetery or his grandfather crying in public for the first time.

His uncle said he sometimes had to bite his tongue when he’d suddenly see his brother’s eyes behind Plowman’s gaze.

“It’s amazing because the boy never knew his father, but he’s exactly like him,” John Plowman said.

Plowman understands this now. He recognizes himself in his 21-month-old son, Andrew.

His eyes mist when he thinks of what he missed and what his kids would miss if he were suddenly gone. When he leaves the house on business trips, sometimes it’s hard for him not to cry.

“I don’t want them to be in the position that I was in growing up,” Plowman said. “I want to be there for them. I want to teach them things. I want to share things with them.” He paused for a minute as he reached down to swing Andrew onto his hip. “I just want to do the things that a dad does with his son, like throw a ball in the back yard.”

‘The Time Had Come’

When military officials called Plowman about his father two years ago, he’d all but forgotten that the search was still going on. He had received periodic updates about the investigation’s progress in the mail over the years, but life for him had moved on. His wife, Angie, was pregnant with their third child. They were closing on a new house. He was busy at his job.

“I remember telling him there was a message about his father, and I remember thinking that was strange because they’d never called before,” Angie Plowman said.

A week later, military officials and a forensics analyst were sitting at Plowman’s dining room table, detailing the decades-long journey that led them to his father’s remains.

In 1993, a team of American and Vietnamese researchers traveled to Ha Bac Province to look for the crash site. The investigation stalled until they found an account of the crash in a newspaper at the Vietnamese National Library in April 1994. The next big break came in January 1996 when they interviewed two locals in the village of Huon Son who said they had witnessed the crash.

A few months later, the team began excavating the site the villagers had identified and turned up charred fragments of human bone scattered amid the thick vegetation. Investigators asked Plowman’s uncle and a cousin for blood samples so the fragments could be tested for a DNA match. In time, tests on a four-inch fragment of bone turned up a match for Plowman’s father, but there was no conclusive match for Ellison, according to a Defense Department report.

Calls to Ellison’s son, Andrew Ellison of Lynchburg, and to Ellison’s brother, Ted Ellison of Utah, were not returned. But Plowman said a Navy official had told him that Ellison’s family has so far rejected investigators’ findings. In a May 2004 interview, Ted Ellison said his family is not convinced that Buzz Ellison was killed on that hill.

Plowman is convinced. Ever the skeptical prosecutor, Plowman initially asked if he could conduct his own DNA tests, but this week he decided to sign off on the Defense Department’s findings.

“The time had come where I just had to get it done and put this away,” he said.

He knows it might be painful for his family to bury his dad all over again. When Plowman told his uncle he wanted a Navy funeral for his father, with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, he sensed a hesitation.

“He said, ‘You know we already had one of those.’ I said, ‘Yeah, but I didn’t,’ ” Plowman said.

Soon he will, though. Maybe then a son’s borrowed memories of his father will finally come to rest.

Father and Son, Separated by War, Crash and Disappearance, United

Courtesy of the Washington Post

James E. Plowman Jr. was just a boy when he first visited Arlington National Cemetery all those years ago. It was a different time, and the country had just finished fighting a different war. He didn’t know then how much he would miss a father he had never met — or that he’d be back 35 years later to say goodbye, again.

But there he stood yesterday, teary-eyed, searching the blue early autumn sky as four Navy jets streaked overhead. He and his family had waited years for this moment: Navy Lieutenant James E. Plowman Sr. was home at last.

A Navy officer presents James E. Plowman Jr. with the American flag at his father’s burial with full military honors.

His burial at Arlington yesterday took place 39 years after he and his pilot, Captain John C. “Buzz” Ellison, were shot down in their A-6A Intruder near the Vietnam-China border. The two were declared missing in action after their plane disappeared from radar March 24, 1967. Their plane went down near a village in Ha Bac Province in North Vietnam.

James E. Plowman Jr. was born five months later.

For years, Plowman’s family held out hope that the 23-year-old Navy flier would someday return. Plowman’s relatives wrote letters to members of Congress. They sent care packages to Vietnam. All that returned was silence from Hanoi. When the young Plowman began to call his grandfather “Dad,” his mother, Kathy Super, decided it was time to let go. She asked the Navy to declare James Plowman Sr. killed in action in 1973, and a ceremony was held at Arlington shortly afterward.

Up until about two years ago, James Plowman Sr. was counted among the more than 1,800 Americans still missing in Vietnam. But his remains were found after a team of U.S. and Vietnamese researchers traveled to Vietnam’s Ha Bac Province in 1993 to look for the Intruder’s crash site. Many false leads and many years later, the team found charred fragments of human bone scattered at the crash site. Tests on the remains showed a DNA match with Plowman, but there was no conclusive match for Ellison, according to the Defense Department.

The news was a relief for the Plowman family but it also reopened old wounds. When the Navy offered this year to hold a second funeral ceremony at Arlington, Plowman, now with a family of his own in Leesburg and a job as Loudoun County’s chief prosecutor, initially was not sure.

But yesterday, as a Navy band played a few feet from his father’s flag-draped coffin, he was more certain. “Every time I hear things about him, I miss what we could have had,” Plowman said. “I know we would have had a good time together.”

Many of the more than 60 people who stood by his side remembered the good times they had with his dad. Some remembered with a smile the young Navy pilot’s love of a good joke and fast cars. Some recalled the day a Navy chaplain and an officer strode solemnly to the door to deliver the news about Plowman’s downed fighter jet. As sailors in ceremonial white uniforms fired a three-gun salute yesterday, still others thought of the long years of waiting for news it seemed would never come.

Many also remembered how the younger Plowman had been at his mother’s side when the Navy honored his father at Arlington the first time. They called the boy “Little Jimmy” and said he was probably too young to remember much about that long-ago ceremony.

This time, he said, he’ll remember every minute.

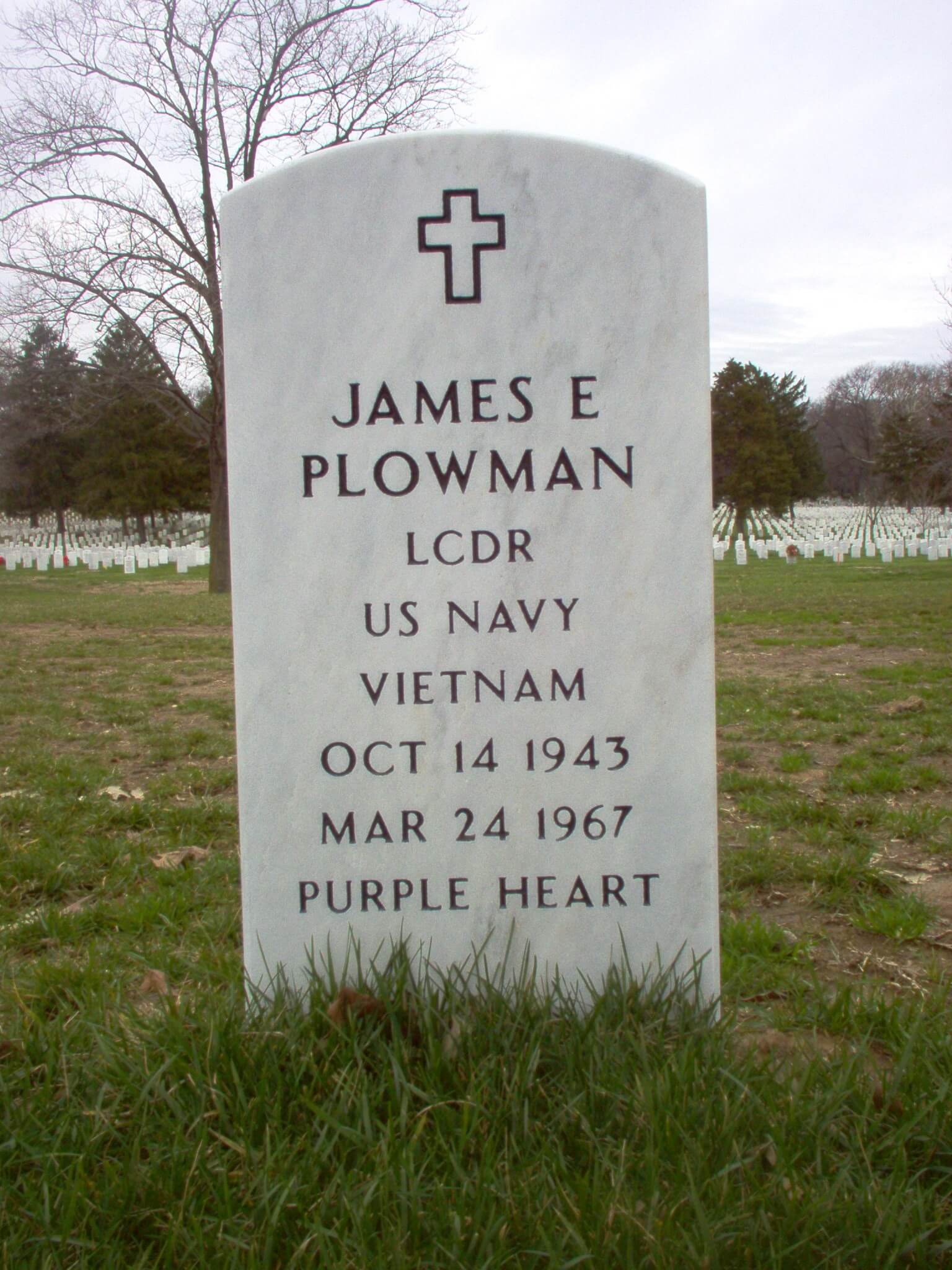

PLOWMAN, JAMES E

LCDR US NAVY

VIETNAM

- DATE OF BIRTH: 10/14/1943

- DATE OF DEATH: 03/24/1967

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 639

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard