NEWS RELEASE from the United States Department of Defense

No. 113-05

IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Feb 01, 2005

DoD Identifies Marine CasualtiesThe Department of Defense announced today the death of three Marines who were supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Lance Corporal Jason C. Redifer, 19, of Stuarts Draft, Virginia

Lance Corporal Harry R. Swain IV, 21, of Cumberland, New Jersey

Corporal Christopher E. Zimny, 27, of Cook, Illinois

All three Marines died January 31, 2005, as a result of hostile action in Babil Province, Iraq. They were all assigned to 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division, II Marine Expeditionary Force, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Local Marine killed in Iraq

By MICHAEL L. OWENS and BOB STUART

Courtesy of The News Virginian

Wednesday, February 2, 2005

STUARTS DRAFT – Lance Corporal Jason C. Redifer was on his final mission in Iraq early Monday when a roadside bomb killed him just south of Baghdad.

The 19-year-old Marine was to return to his Stuarts Draft home next week, where his mother, Rhonda Winfield, and family awaited him.

“He was my best friend,” she said Tuesday night. “He would have given his life for any of his friends, and it’s backed by the fact that he just died for people he didn’t even know.”

Redifer was among three Marines killed during fighting Monday in Iraq’s Babil Province, the Pentagon said. The two other Marines were from New Jersey and Illinois.

His mother spoke with him by telephone roughly two hours before he died. She was devastated to return home from work that afternoon to find a pair of Marines at her doorstep.

“When there’s been an injury or something, they just call you,” she said Tuesday.

“I just looked at them and told them not to give me any bad news, and they both dropped their heads.”

Redifer worked three jobs to afford a high school education at Stuart Hall, a private school in Staunton where he graduated in 2003. He joined the Marines days after graduating.

Former classmates, teachers and other staff at Stuart Hall mourned Redifer’s death Tuesday.

Carol Shriver, the director of studies, the chaplain and a teacher of philosophy and religion at Stuart Hall, said Redifer decided to enter the military because of the 9/11 attacks.

“Jason made a conscientious decision to serve his country,’’ she said. “He has two younger brothers. He wanted the world to be safe for them. If he thought he could make it a better world for his younger brothers, he would do that for them.”

Connie Davis, the Stuart Hall school nurse, recalls Redifer as a student fiercely determined to get his education. One of his jobs involved cleaning chicken coops.

“He worked three part-time jobs to pay his tuition because he valued his education,’’ Davis said, adding that he rose at 5 a.m. to begin his long days.

“He was a young man of such character, who had such love for his mother and three brothers,” Davis said. “Any one of us would have been proud to call him our son.”

Davis said Redifer was proud to be a Marine and to serve his country.

“We are all better for knowing him. He was just a treasure of a human being,’’ she said.

Redifer died from a bomb blast that ripped his Humvee, the military said.

Stuart Hall staff and students received an e-mail from Redifer as recent as Friday.

“Jason lived every minute of his life, and he would not want us to be sad,’’ Shriver said. “He lived life to the fullest. I miss him greatly.”

Redifer wanted a lifelong military career, said stepdad Scott.

Winfield, maybe studying law in college and joining the Judge Advocate General’s Corps.

In the short term, Redifer “wanted to ride his horse” as soon as he returned home.

“He was pleased to be there, and he was proud to be doing what he was doing,” Scott Winfield said.

Lance Corporal Jason Redifer, 19, of Stuarts Draft, Virginia, died Monday when the Humvee he was driving hit an improvised-explosive device, according to his family.Redifer was in the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division, II Marine Expeditionary Force, which is based at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Three Marines in the unit were killed Monday in the northern Babil Province, south of Baghdad, according to a release put out by the Marines. Additional information about the incident could put the men in the unit at greater risk, according to the release.

The dead Marines were not identified, and a spokesman reached Tuesday said he could not talk about the incident until 24 hours after official notification of the family.

Redifer survived six previous improvised-explosive device attacks, his mother, Rhonda Winfield, said.

Redifer, a 2003 graduate of Stuart Hall, was scheduled to return to the United States February 9 and home to Stuarts Draft on February 15.

Remembering RediferSome touching mementos at a Valley school shined through Thursday’s falling snow.

Students have started leaving flowers beneath a tree at Stuart Hall in honor of fallen alum Jason Redifer.

Redifer was serving as a Marine in Iraq when he was killed on Monday.

The new flowers join a yellow ribbon that has been on the tree for some time honoring Stuart Hall military members.

Redifer’s body was returned to the U.S. Wednesday night and his family said it will be brought to Stuarts Draft for a funeral service.

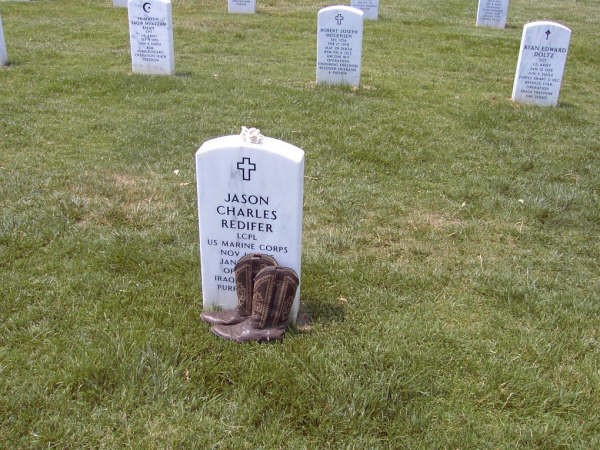

He will be buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Flags Flying at Half-Staff

Many local flags were raised this morning, but only to half-staff.

This is being done to honor the death of Marine Lance Corporal Jason Redifer of Stuarts Draft.

Delegate Chris Saxman asked Staunton, Waynesboro and Augusta County to move flags to half-staff earlier this week.

The flags will fly like this until Redifer is buried in Arlington National Cemetery on Tuesday.

Redifer’s body is being returned to Stuarts Draft on Thursday.

There will be visitation at Calvary Methodist Church in Stuarts Draft on Sunday from 2-4.

The funeral will be there on Monday at 11 am.

3 February 2005:

Rhonda Winfield proudly sported a T-shirt early Wednesday that displayed a heart-framed picture of her son, Lance Corporal Jason Redifer, decked out in his Marine finest.

“I have a part of my heart in Iraq,” the caption stated.

For six long months, it served Winfield as a keepsake reminder of her son, a 19-year-old sniper stationed just outside Baghdad since July. The shirt was to come off for good upon his return home to Stuarts Draft next week.

The teary mother burned the shirt in her backyard at precisely 4 p.m. Wednesday, the time when Redifer’s body was scheduled to arrive in the United States aboard a military cargo plane.

“He won’t be here with us, but in a way, he’ll be home,” Winfield said.

A roadside bomb ripped through a Humvee and killed Redifer early Monday during his last mission in the war-torn country.

On Wednesday afternoon, his aunt, Rita Lockridge, didn’t mind watching the gift she bought for Winfield go up in symbolic smoke.

“I wanted him to know where my heart was, and my heart will always be with him,” she said.

She considered Redifer as more of a “buddy” than a nephew.

To teachers and administrators at Stuart Hall, Redifer was both a country boy with a mischievous streak, and a passionate patriot who postponed college plans to serve his country.

On Wednesday, two days after he lost his life while serving his country, the Stuart Hall family continued to struggle with his death.

Counselors remained on standby for students, and a memorial service is planned at the school at a later date, following Redifer’s funeral.

A table of tribute filled with messages from Stuart Hall students sits in a school room. Eventually, the table of messages will be given to Redifer’s mother, said Sherry Cox, Stuart Hall director of communication.

The school also has an oak tree on its campus out front where tributes will be offered in the memory of the 19-year-old Redifer, who graduated in 2003 from Stuart Hall, a private school that he could afford to attend only by working three part-time jobs.

On the state level, Governor Mark Warner received a request Wednesday from local Del. Chris Saxman to lower state flags in Staunton, Waynesboro and Augusta County in Redifer’s memory.

The governor’s office is waiting for official notification from the U.S. Defense Department of Redifer’s death before handling the request.

Sitting in the tribute room at Staunton’s Stuart Hall on Wednesday were several teachers and administrators who could only think of a fun-loving Redifer, a real-life teenage cowboy who donned boots and hat during the school’s monthly dress-down days. All other days they wear uniforms at Stuart Hall.

“He lived for whatever he believed in,’’ said math teacher Beth Hinkle. “He was a person full of life who could make anybody laugh. We’ll forever see him in his cowboy hats and boots.”

Hinkle also remembers a young man who turned down a chance to guard the White House in exchange for duty in Iraq.

“He said, ‘I can’t make a difference standing guard. I have to be over there where I can make a difference,’ ’’ Hinkle said.

Robin von Seldeneck, a college counselor at Stuart Hall, said Redifer worked hard to help his fellow students by tutoring them in math, his favorite subject.

“His death gives the war a face,’’ she said. “I’m not aware of any deaths from the Shenandoah Valley. To know someone who died really makes you think about war.”

Redifer embraced the people of Iraq much like he did his own family and his Stuart Hall family, Hinkle said.

“True to who Jason was, he loved the Iraqi families and saw them in a different light,’’ she said. “He went into their homes.”

Beth Hodge, Stuart Hall’s director of administration, remembers Redifer’s senior chapel talk in the fall of 2002, a requirement of all Stuart Hall seniors.

Hodge said Redifer cradled his two younger brothers in each arm, and calmly told the chapel crowd “about the importance of family.”

“The speech went wonderfully, and was a model for his class,’’ Hodge said.

The impact of Redifer’s death was felt well beyond Stuarts Draft and Stuart Hall, Hinkle said, noting that she informed her 70-year-old parents in Indiana late Monday.

“My parents had heard a lot about him, and they were crying Monday night,’’ Hinkle said. “He affected a lot of people who never met him.”

Redifer’s maturity was apparent at an early age. He worked three part-time jobs to pay his way through the private Stuart Hall.

One of his former employers, Spotswood dairy farmer Kyle Leonard, recalls a boy barely 16 years old who helped him on his dairy farm one summer.

“He kept the place nice, fed the calves and was good with my children. He was a family friend as well,’’ Leonard said.

Leonard could envision a grownup Redifer tending to horses.

“This is a tragedy, and I really feel for the family,’’ Leonard said.

Back in Stuarts Draft, dozens of family and friends flanked Winfield as she burned the T-shirt. Tears of loss mixed with laughable recollections.

Winfield said she has found strength in arranging for her son’s funeral at Arlington National Cemetery. Actually, it was Redifer who planned his own funeral before he left for Iraq. He detailed every aspect of the ceremony – from pallbearers to the song list – just in case tragedy struck.

“I’ve played every one of the details in my mind since the day he left,” his mother said.

Redifer had survived a previous roadside bomb last week, even though he was knocked unconscious.

“He had cheated death from the time his boots hit the ground over there,” his mother said. “He just wasn’t as lucky this time.”

4 February 2005:

The recent spike in military casualties in Iraq has delayed local memorial services and the burial of Marine Lance Corporal Jason C. Redifer of Stuarts Draft at the Arlington National Cemetery, according to the military.

Redifer was killed in action Monday, the victim of an improvised explosive device. He was 19.

Marine Captain Soulynamma D. Pharathikoune, the casualty officer for Roanoke-based Company B, 4th Engineers Battalion, said that Redifer’s remains will be transported “as soon as possible” to the Stuarts Draft chapel of Reynolds Funeral Service, under military escort. Pharathikoune said that the processing center for overseas casualties in Dover, Delaware, was working overtime because of the recent downing of a military helicopter.

Rhonda Winfield, Redifer’s mother, said that she expected her son’s remains to return to Stuarts Draft “sometime next week.” She quoted a Marines spokesman as saying that a closed casket memorial service would be necessary.

According to a Pentagon Public Affairs spokeswoman, Redifer will receive a posthumous Purple Heart medal.

Before his death, Redifer received the Global War on Terrorism Expeditionary Medal and the National Defense Service Medal. He also received the Sea Service Deployment Ribbon.

‘I die with honor’

Mother picking up the pieces after son killed in action

Chris Graham

Courtesy of the Augusta Free Press

Her son was due home from the front lines of Iraq next week.

Next week.

Could you believe it?

It might as well have been five minutes from now, she had been anticipating the moment so.

She could already see him walking up to the door.

“He would have said, ‘Howdy.’ With a cowboy hat on,” said Rhonda Winfield, speaking of her son, Jason Redifer, 19, who had shoved off for the war last July 4, a date whose irony wasn’t lost on anybody.

Jason was “a walking contradiction in terms,” his mother said, forcing a smile as she reminisced in the living room of her Stuarts Draft home about the good times.

“He never would have had an inkling of the power of the positive force that he emitted and that he gave to everybody. He would have told you he was just one of the guys. ‘I’m not the smartest,’ although he was so sharp. ‘You can dress me up every now and then, but … but I’m still just a cowboy.’ He refused to say ‘pretty.’ It was always ‘pur-r-r-rty.’ Sometimes I felt like we ought to black out a couple of his teeth and put a hillbilly hat on him, and he would have done just fine,” Winfield said.

Winfield was awakened early on Monday morning to hear his voice on the other end of the phone line.

“He slipped away and was making a phone call when he shouldn’t have been. Just because he needed to let me know that the elections had gone well, and he was well. And that he was leaving for his final mission,” she said.

“He would be coming home in nine days. This mission would only last three days, which was much shorter than the majority of ones that he had gone on.”

As he spoke, mom picked up on something going on beneath the small talk.

“He had a very guarded tone,” Winfield said. “He said all the things that he always said. He tried to have the same sense of humor. He tried to give me the words of encouragement that I wanted to hear. But he also, I could tell by his tone, knew that this was not a feeling that, ‘I’m in the home stretch.’ This was going to be increasingly dangerous.

“He was making sure that he had all his bases covered with everybody,” Winfield said. “He e-mailed friends, and called friends, and said things that he thought everybody needed to know. But if you knew Jason, he made sure that you knew those things all the time. So it wasn’t like he said anything shocking.

“We chatted a little bit. He told me he could not wait to get off that bus coming home and get his boys (his little brothers, Courtland, 8, and Carter, 6) in his arms. And he was just looking forward to getting this behind him, and looking forward to being able to call me and tell me that this part was done.”

Two hours later, Jason was dead.

Defender

“He would have been furious with me for allowing any sort of pomp and circumstance,” said Winfield, who has busied herself making plans for Jason’s funeral and consoling friends and family members who are themselves having a hard time believing that the light of their lives is gone forever.

And that’s not overstating what Jason Redifer was to everyone who knew him – as unassuming as he was.

“If you would have heard what other people had said about him, and looked at a lineup of 10 people, he would have been the very last person that you would have pegged to have been the owner of that personality,” Winfield said. “He never met anybody that was uncomfortable. He never met anybody that he would have judged or wouldn’t have liked. If he could find one glimmer of redeeming light in you, he would have defended you to the end.”

Jason was the world’s defender long before he signed up for the United States Marine Corps, to hear his mother tell it.

“I cannot tell you how many times he would come home and would have been in a confrontation with somebody. And that was so unlike him. He wouldn’t ever want to be negative to anybody,” Winfield said.

“I would say, ‘What on Earth happened?’ ‘Well, I was just walking through the Wal-Mart, and the next thing, I heard this ruckus over in produce.’ And then he would go on, and somebody would have done something unjust to somebody else, and he didn’t have a phone booth, so he just jumped into his cowboy boots instead of his Superman cape, and he made it his responsibility to save the day,” she said.

“Sometimes it panned out, sometimes not, but it never slowed him down from keeping on.”

The reluctant rifleman

That he ended up being the sniper for his Marine Corps unit is an accident of life – one of those things that will never be explained.

“It was the most bizarre thing about that. His older brother (Justin, an Army reserve) has always been the sportsman. He’s always been the rifleman, enjoyed hunting. Jason went one time. He shot a squirrel, and couldn’t wait to rub it in his brother’s face. He got it on the first shot, first shot. But then the gravity of having taken the life of something overwhelmed him. And he was so upset by it when he came home. And while he liked to target shoot, he said, ‘I will never take a life again.’ So it was a very strange turn of events that this was his occupation,” his mother said.

“He was just so skilled with the rifle, and he just said, ‘As it turns out, who would have thought, but I’m very good at my job. And if that’s where my talent lies, and that’s where my contribution has to be to make a difference, then that’s what I’ll do. And as long as I can look into the eyes and see some hope in some children here, then that’s going to wipe out the look in the eyes that I see at the end of the scope.’

“That’s what he had to cling to.”

The fall

Winfield got home from work a little after four Monday afternoon to find an unmarked van with government tags parked in the driveway.

“And your first thought is, ‘Gosh. There’s no way,’ ” she said.

“Part of me thought quickly, ‘Well, we’re dairy farmers. It could be someone checking water quality.’ I picked up my cellphone to dial his number to get some affirmation that he was OK.

“As I was dialing the number, Scott (her husband) and two Marines in full dress blues came around the corner. And you know when you’re a Marine mom that when they come to your door, it’s not to tell you, ‘Hey, the mission went well, and your son is going to come home in nine days.’

“The shock, that first moment of denial, you think that you can backpedal a few steps, not get out of the car, or you can make it go away,” Winfield said.

“I got out of the car, and they had the we’ve-come-to-tell-you-about-a-death look on their face. And so I took I’m-going-to-yell-at-them-and-tell-them-they-cannot-tell-me-any-sort-of-bad-news-about-my-son-and-scare-the-Marines-away approach.

“They were Marines. It didn’t work.”

The soldiers were patient, Winfield said, “while I came unglued.”

“Somehow, you change channels in the midst of all of it, and you realize that you have to hear them say the words, you’ve got to hear every single detail that they can give you. Because you’re going to need it later. And then you’ve got to figure out where you go, and what you need to do.

“And if you let yourself fall down then, I don’t know that you can get back up.”

Evening news

Jason had often warned his mother not to watch the evening news – not because of what she would see, she said, but because of what she could not see.

” ‘Because you know what you don’t get to see?’ He told me this once, and it put it all in perspective,” Winfield said. ” ‘You don’t get to see the woman who lives in a house with 15 other people that has nothing, and as you walk in in the middle of the night, and they see nothing but you and your full battle gear, and your rifles, and rather than revealing that you’re there, or that they’re angry, it may be one house in a thousand, but that one time that people look at you like you’re the cavalry coming in to give them promise, and that one person who will want you to sit down and have tea with them, and give you what little they have, you can’t see that, and you can’t know what that feels like.’ “

The movie

“After the initial shock, after hearing it out loud, I took a breath. And then you go to the business end of things that you’ve done in your mind since your child left for boot camp,” Winfield said.

Before Jason had left for Iraq last summer, he had laid out plans for what the family should do in the event that something happened to him in the Middle East.

“I knew what he expected to be done in honor of the situation. I knew what he would want me to do,” Winfield said. “I also knew what he looked like in those dress blues. And I could envision what he would look like if he came home in a casket.”

Against Jason’s wishes, she found herself watching the television news regularly.

“And every time you ever heard of a horror on the news, involving a soldier, you have that thought in your mind, and that movie in your mind telling you what to do when something happens starts to play,” Winfield said. “And then, of course, when you hear something, and you realize you’re OK, everything’s OK, it’s ‘OK, rewind.’ “

The movie telling her what to do when something happens is playing full time in her head now.

“That first night, trying to make yourself realize that you’re living the movie now, that it’s not a replay, that was hard. You can’t rewind now. You can’t rewind,” Winfield said.

“I know that as difficult as that first night was and that all of this has been, it’s when all the people go home, and you’re left with just your thoughts, and your realization of ‘here we are,’ this at least I’ve practiced. The hard part starts after he’s been laid to rest, and I have to figure out how to live life without Jason,” Winfield said.

“People can tell you what to expect in this process, what you should do in this process, how grand a burial at Arlington will be. They can say all those things, and help you fill in the gaps, and help you steer yourself through whatever is coming,” Winfield said.

“But there’s not another person in this world who has ever been Jason’s mother, or has lost him, or has any kind of clue how I am going to live without him. That’s when the hard part comes. This part, we just do.”

‘I die with honor’

“You couldn’t feel anything else. You couldn’t feel anything other than so proud,” Winfield said, her eyes glistening.

“They had heard me boast about God and country since they hit the ground running. Who could I be to stand up and say it, if I thought, gee, it was OK for everybody else to send their child, and not let yours go? So … I know he’s pretty ticked off at this minute because he didn’t get to get home and square things with his brothers. But aside from that, he’s feeling he wrapped things up in a pretty good way,” she said.

As for mom …

“I’ve never claimed to understand many of the things that Jason has gotten notions to do. Nor have I supported many of the things that he had gotten the notion to do. But he was so proud of this. And he felt like he was laying down a legacy for his brothers that would be something that he could be proud of,” Winfield said.

He said, ‘We lose people every single day. Statistically speaking,’ and if I heard that one more time, I’d have throttled him myself, ‘if I don’t come home, I die with honor doing something they can be proud of, and not everybody can say that.'”

A last goodbye

Stuarts Draft Marine buried at Arlington

She had to touch that compassionate Marine whose eyes betrayed his stoic face.

Rhonda Winfield was about to bury one of her sons — the kind of boy who makes a momma proud.

He was, after all, a U.S. Marine. Just like that man holding out the American flag. The same one that draped over Jason Redifer’s coffin for days while friends and family mourned. That flag that sharply dressed men carefully folded at the end of a grueling week and a half.

And so when Gunnery Sergeant Brady Baker leaned over to offer his sympathy, well, there wasn’t much that mom could do.

“He is just one of the many Marines that have been encouraging throughout this entire ordeal, that have looked at us with so much pain and empathy, that have made us feel like they genuinely were hurting,” Winfield said hours after the burial. “When he explained his sorrow for my loss … I just felt I had to touch him.”

Today her son, a Lance Corporal, was supposed to come home from Iraq. His tour of duty would be over.

Tuesday, his family and friends buried Redifer at Arlington National Cemetery alongside thousands of other soldiers, other Marines killed in the line of duty.

It was a simple decision, really, to bury him nearly three hours away from his Stuarts Draft home.

“Jason would absolutely argue all the pomp and circumstance,” Winfield said. “But he’d be extremely proud that his younger brothers could visit and feel pride in their country.”

There are, after all, presidents buried at Arlington — John F. Kennedy and William Howard Taft. Supreme Court justices and Army Generals lay there too.

And so are 113 other soldiers who died in Iraq, buried here before Jason.

He was given military honors. The Marines provided a salute. The Navy, a prayer. And “Taps” came across a silver trumpet.

His family and friends, some wearing the cowboy hats that Jason loved, filled the graveside service. More than 200 came.

Amanda McConnell was among them. One of Redifer’s best friends from Stuart Hall, she flew home from college in Michigan to attend. Seeing her classmate buried at Arlington was surreal, but it’s what he would have wanted, she said.

“He would have been honored to be among the men and women at Arlington,” McConnell said.

From now on, whenever she visits Washington, there’s a friend across the Potomac she plans to see. And whenever his family can visit they will take pride knowing he died for his country.

“I don’t want to go and sit by just a piece of ground and mourn my son,” Winfield said. “I want to honor his life.”

Among simple white marble stones near the corner of York and Marshall, two small drives inside the 624-acre cemetery, a 19-year-old Marine rests with honor.

Virginia Marine Kept ‘Fighting Good Fight’

Marksman Died on Patrol in Iraq

By Jerry Markon

Courtesy of the Washington Post Staff Writer

Wednesday, February 9, 2005

As dozens of grief-stricken family members and friends looked on, a Marine sharpshooter killed in Iraq was laid to rest yesterday at Arlington National Cemetery.

The funeral for Lance Corporal Jason C. Redifer, 19, was attended by about 100 people from his home town of Stuarts Draft, Virginia. They filled two large red and white buses, one paid for by a church and the other paid for by the local Veterans of Foreign Wars, and headed to Arlington yesterday morning.

Redifer was killed with two fellow Marines, Lance Corporal Harry R. Swain IV, 21, of Cumberland, New Jersey, and Corporal Christopher E. Zimny, 27, of Illinois, in hostile action in Iraq’s Babil Province on February 1. The men were assigned to the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division, II Marine Expeditionary Force based at Camp Lejune, North Carolina. The military has not released details about how they died, but friends said it was a roadside bomb.

Redifer is the 114th service member killed in Iraq to be buried at Arlington. He died about two hours after calling his mother at the family’s dairy farm in the Shenandoah Valley.

“He had only one mission left and he was leaving Iraq in nine days to come home” on furlough, his mother said in an interview after his death.

His parents described Redifer as a top-notch Marine who had an opportunity to join the White House honor guard but turned it down because he did not want any child’s parent to go to war in his place.

Winfield said her son frequently told her that he didn’t know “if what we are doing [in Iraq] ever will” make a difference, but that “you’ve always got to believe that it can and keep fighting the good fight.”

Redifer’s father said his son was “very proud of being a Marine. . . . He told me quite a few times how he was proud of being a sniper and getting his expert’s marksmanship with his rifle.”

Redifer said Jason and his older brother, Justin, who is a military policeman based in West Virginia, “both made us proud. Anytime I would see any of my family members or friends, they would say how grown-up both of the boys acted, how nice and respectful they were, even at a young age.”

The grief “is hard to put into words,” he said.

Others who knew Redifer have described him as an old-fashioned patriot. In his school yearbook, Redifer quoted President John F. Kennedy’s famous inaugural address: “And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

Friends said Redifer did not have to go on the patrol that fell victim to a roadside bomb, but that it was in his nature to do so. Redifer had been wounded a few days earlier by an improvised bomb, they said, but was determined to fight on.

Redifer was buried in Section 60 at Arlington, among three rows of soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. The rest of the section contains soldiers killed in conflicts ranging from World War II to Somalia.

Navy Chaplain John Miyahara conducted the brief Protestant service under an arrangement of red, white and yellow flowers. A Marine firing party fired three rifle volleys. As taps were sounded, Redifer’s mother wiped away tears.

Family Now Mourns Murder Victim Along with a Lost Marine

All eyes are now focused on Weyer’s Cave murder victim, Cecil Redifer. Just a few months ago, eyes were on his fallen son.

39-year-old Cecil Redifer, shot to death late Wednesday morning, was already well known in the Augusta County community. Reporters’ cameras were pointed at him earlier this year, as he grieved the loss of his son. That son, 19-year-old Jason Redifer, was the first Augusta County serviceman killed in Iraq.

Jason, of Stuarts Draft, was killed in late January when his humvee drove over an explosive device in Iraq. He was part of the Marine Corps Infantry Division and was on his final mission in Iraq when he was killed. Jason Redifer is buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

Right now, Augusta County Sheriff’s authorities are not releasing any known motive for the murder of Cecil Redifer.

August 26, 2005:

A murder investigation that led to a daylong search in Augusta County woodlands ended with the suspect’s suicide yesterday morning, police said.

Investigators with the Augusta Sheriff’s Office believe that James Almond, 45, abducted his wife Wednesday morning and later shot to death Cecil Redifer, 39, outside Redifer’s home in Weyers Cave.

The ensuing search for the couple involved police dogs and as many as 40 people from the sheriff’s office, the Virginia State Police, the U.S. Forest Service and other agencies who tracked them to national forest areas in western Augusta County, police said.

At about 9 a.m. yesterday, Almond released his wife, Tammie Almond, 44, in the Camp Todd area of the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, Sheriff Randy Fisher said at a news conference.

Shortly after that, Tammie Almond and a man who ushered her to safety heard a single gunshot that authorities believe was James Almond committing suicide, Fisher said.

Tammie Almond was bruised from an apparent beating. The discovery of her husband’s body about an hour after her release closed the case, the sheriff said.

“The perpetrator in this thing is dead. There will be no charges,” Fisher said.

He described the motive behind the killing as “an ongoing domestic situation,” but would not elaborate.

The Almonds lived in the rural, mountainous Churchville area, northwest of Staunton. They’d been married some 13 years.

Redifer was the father of Marine Lance Corporal Jason C. Redifer, 19, who was killed by a roadside bomb in Iraq in January.

Tammie Almond worked with Cecil Redifer at a packaging plant in Weyers Cave, an Augusta County town northeast of Staunton.

Almond and her husband had an altercation early Wednesday morning in which James Almond beat her and refused to let her go to work, the sheriff said.

Almond abducted his wife and drove her to the parking lot of the packaging plant, where he waited for Redifer to leave for lunch. Almond told his wife that he just wanted to talk to Redifer, and followed him to his home, Fisher said.

“I’m not sure Mr. Redifer was aware that he was being followed,” the sheriff said.

At 11:35 a.m., the sheriff’s office received a call from Redifer’s neighborhood about two gunshots. Authorities found Redifer’s body about 20 feet in front of his front door, with wounds to his front and side inflicted from a high-powered rifle, Fisher said.

About four hours later, police found the white, 2000 Dodge pick-up the Almonds were in. It was abandoned in the national forest area in western Augusta. James Almond was an avid hunter who knew the terrain well, Fisher said.

The couple apparently spent the night atop a mountain in national forest area. In the morning, Almond told his wife that he couldn’t kill her, but that he would kill himself, and released Tammie Almond. She walked away and was given a ride minutes later by a man driving a pickup truck.

REDIFER, JASON CHARLES

LCPL US MARINE CORPS

- DATE OF BIRTH: 11/14/1985

- DATE OF DEATH: 01/31/2005

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 8095

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard