“T.S. Eliot once called April the cruelest month,” Gen. Henry Shelton reminded a crowd of 200 who gathered on a cold, rain-soaked day at Arlington National Cemetery last week. April 2000, as Shelton noted, had its share of sad anniversaries for the U.S. military.

Most of the attention focused on the 25th anniversary of the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975. But another sad day in U.S. history was remembered at the Tomb of the Unknowns on April 25, the 20th anniversary of Desert One.

Eight Americans were killed April 25, 1980, in the botched attempt to rescue 53 U.S. hostages who were being held by Iranian radicals at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran.

President Jimmy Carter had ordered the rescue attempt after six months of frustration over Iran’s refusal to release the hostages. The operation, named Eagle Claw, was not a simple one.

Helicopters flying from a carrier in the Persian Gulf were to ferry Delta Force commandos to a location outside Tehran from which the rescue would be launched. First the helicopters would have to rendezvous for refueling with C-130s flying from a base in Oman at a spot in Iran labeled Desert One.

A swirling sandstorm and mechanical problems forced two helicopters to drop out. As the forces gathered at Desert One, a third helicopter developed a hydraulic leak. Deciding he no longer had the force needed to succeed, the commander, Army Colonel Charles Beckwith, scrubbed the mission.

Matters turned disastrous shortly after that when one of the helicopters collided with a C-130 transport plane loaded with fuel. Eight men died in the resulting fireball. The rest escaped, but the mission’s failure spelled doom for the Carter administration and forced the military to rethink how it conducted joint operations.

The focus last week at Arlington was not on the failures.

“When I think about the sheer audacity of the Eagle Claw mission, when I consider the enormity of the task . . . when I examine the political situation at the time in both Iran and America, and when I reflect on the results–both positive and negative–I am awed,” Shelton, who is chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told those gathered. “I stand in the company of giants and in the shadow of eight genuine American heroes.”

Relatives of many of those killed were on hand for the ceremony, sponsored by No Greater Love, a Washington-based nonprofit dedicated to caring for the families of Americans who died in service to the country.

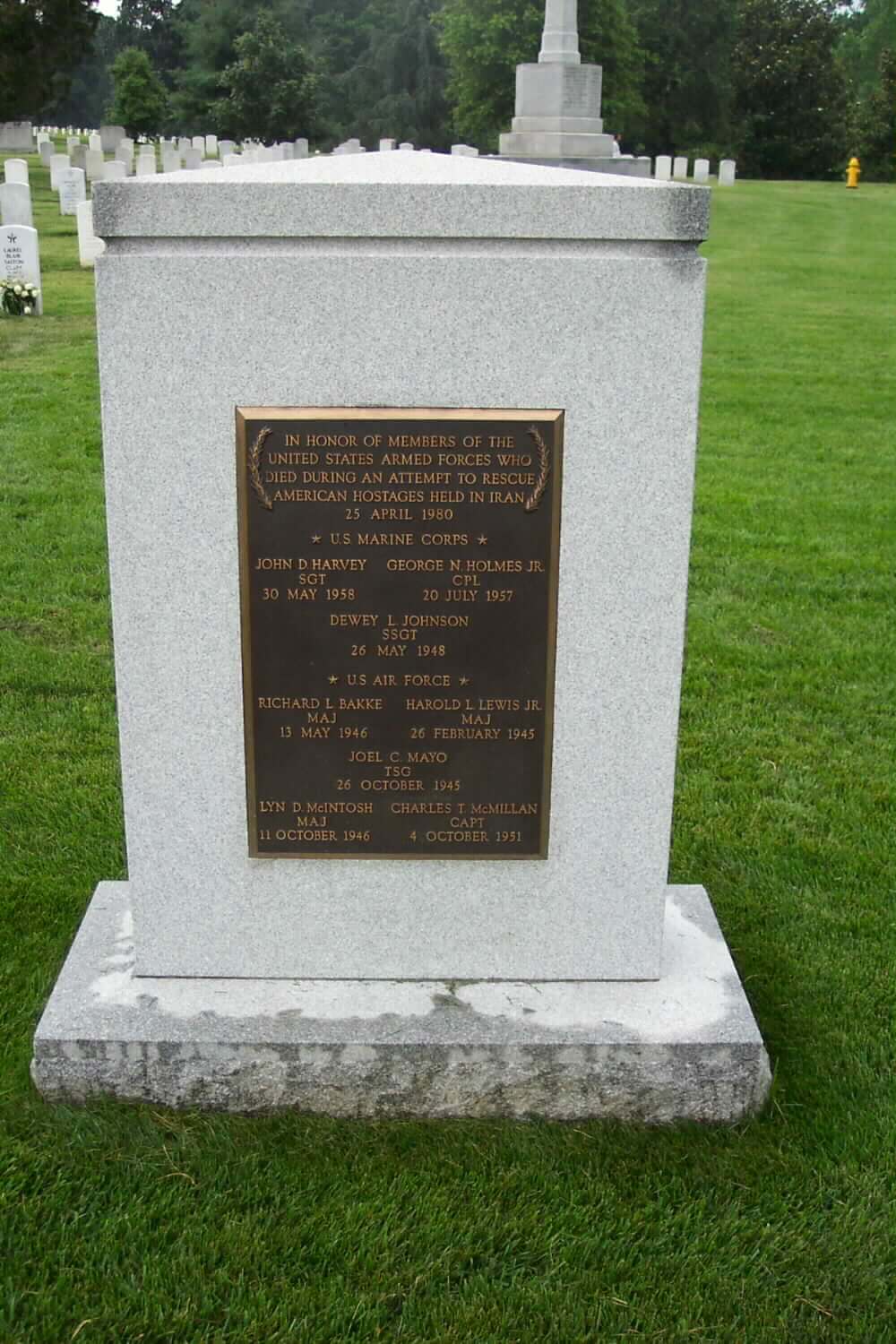

Many veterans of the Desert One operation also attended, and they escorted family members as they placed roses on the common grave of three of the casualties. Nearly a dozen former hostages saluted the sacrifices made on their behalf by placing U.S. flags on a remembrance panel.

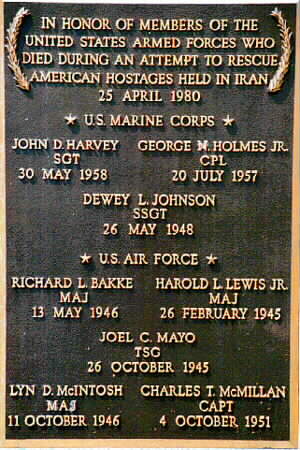

The eight servicemen honored included three Marines: Sgt. John D. Harvey, of Roanoke; Cpl. George N. Holmes Jr., of Pine Bluff, Ark.; and Staff Sgt. Dewey Johnson, of Dublin, Ga. The five Air Force personnel honored were Maj. Richard L. Bakke, of Long Beach, Calif.; Maj. Harold L. Lewis Jr., of Fort Walton Beach, Fla.; Tech. Sgt. Joel C. Mayo, of Harrisville, Mich.; Capt. Lyn D. McIntosh, of Valdosta, Ga.; and Capt. Charles T. McMillan of Corryton, Tenn.

Lauren Beth Harvey–at 21, the same age as her father, John Harvey, when he died at Desert One–read the No Greater Love “Pledge of Peace.”

Shelton compared the Iranian mission to the 1804 raid on Tripoli led by Lt. Stephen Decatur. “Just as the Tripoli raid was the most daring act of its age, Eagle Claw was one of the most daring acts of our age,” Shelton said. “That it did not achieve its objective does not detract in any way, in any measure, from the heroism of those who tried.”

25 July 2006:

The Howland native was on the crew of an ill-fated rescue mission.

The unsuccessful attempt to rescue 53 Americans hostages in Iran in April 1980 was a life-defining event for recently retired Air Force Colonel Jeffrey B. Harrison.

Harrison, a former Howland resident, was injured during the mission when a helicopter rotor sliced into his C-130 Hercules cargo/transport, causing both aircraft to burst into flames.

One of five crew members injured, Harrison recovered from burns suffered to his face, neck and shoulder.

Others were not so fortunate. Five Air Force crew members on the C-130 and three Marines on the helicopter perished in the crash.

Harrison was safety officer aboard the C-130 that was part of a military team sent to Iran to rescue the American hostages.

For many Americans, the Iranian hostage saga is perhaps only a distant memory. But for Harrison, a 1972 graduate of Howland High School, it remains as vivid today as when it happened.

His mother, Lois Harrison, said the experience “fueled” her son’s decision to make a career in the Air Force.

Harrison visited his mother in Howland last week from his civilian home in Springfield, Virginia, and was interviewed by telephone.

He described his feelings about the events that deadly day in April 1980 as guest speaker in April 2000 at the 20th anniversary Remembrance Ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery to honor those who died in the Iran Rescue Mission.

“Sometimes it’s like watching a movie because it is so vivid and you remember it so clearly. And those seconds just turn to minutes. Time just shuts down,” he said at the ceremony.

Tragic accident

According to a newspaper account, the helicopter-and-C-130 crash occurred about an hour after the mission had been officially aborted at 2:30 a.m.

What happened next could not have been expected or planned for.

One of the choppers was refueling and drained one of the C-130 tankers before its own tanks were full. When the helicopter lifted and banked away from the empty tanker to cross a road and top off its tanks from another fuel plane, the rotor sliced through the fuselage of a C-130 loaded with troops. Both aircraft burst into flames.

Harrison, who was on the burning transport, said he didn’t do anything different or any better than his five crewmates who died in the crash.

“It was simply God’s grace” that he lived, Harrison said.

In November 2000, Harrison was reunited with the surviving C-130 crew members for the first time in 20 years.

Though he had had periodic contact with some of them over the years, he said it was a “joy to see everybody back together again.”

Despite the deaths and failure to bring back the hostages, Harrison said he and the others on the all-volunteer mission do not see it as a failure.

He attributed the negative outcome to the “fog of war. In war, stuff happens.”

Bright side

On the positive side, he said some tactical firsts, such as the use of night vision goggles to fly in formation, refuel in the air and land, were originated for the Iran hostage mission, officially named Eagle Claw.

Harrison doesn’t blame the crash in which he was injured, referred to as Desert One, on anyone.

“The helicopter was in a dust cloud. It wasn’t a factor of being less professional or less capable. It was just one of those things,” Harrison said.

Close calls

He noted the accident was not the only close call on the mission.

“We almost had a collision on the ground before we even launched that night. There was a mix-up on the taxi plan and an airplane took off that was not supposed to take off.

“We did not have night vision goggles on for takeoff. But it just so happened that the co-pilot put a pair on and saw the other plane coming toward us. He yelled. ‘Abort, abort, abort,'” Harrison said.

He said his pilot immediately hit the brakes and moved as far to the right on the runway as possible.

“We still would have collided, but the other plane went off the runway into the dirt, causing its wing tip to lift up and allow our wing tip to go over his.

“My hat’s off to the pilots. That was the first opportunity for something bad to happen to our airplane. You have to be ready and flexible and know enough about the equipment and people to make the right decisions,” he said.

“There are a lot of those kinds of stories” connected to the mission, Harrison said.

Effects

He said the event affected his life on several levels, including his decision to stay in the military.

“My original intent was to pay back my years of commitment and decide after that. The mission helped me develop an appreciation for the camaraderie and the professionalism and the family atmosphere in the military. It pushed me over the edge and probably helped me stay a lot longer than I expected,” Harrison said.

It even changed his politics.

“I grew up in a Democratic, liberal family. But the very nature of those experiences, in my case, drove me to more of a conservative outlook. I’m a little bit left of center, but I consider myself a pretty conservative person, with a pretty open mind.

“I have certain values I live by — integrity and a moral code you develop. I try to judge the character and personality of a person running for office on the basis of their platform and what they stand for. I’ve voted both parties,” he said.

The experience also left him with flashbacks for a while.

“There were times I woke up in cold sweats and nightmarish moods. Of recent years, no,” said Harrison, who spent most of his 30 years’ service flying or in command positions with special operations units.

His military experience even defined his plans for the future as a civilian.

He said he doesn’t know exactly what he will do, but he wants his second career to be as meaningful and enjoyable as serving his country in the military.

“Once you leave the military, you want to give something back to the nation for all the support it provided you all those years,” he said.

One thing he definitely wants to do is locate some of his former teachers.

“I attribute a lot of what I have accomplished to the educators that taught me and were my mentors as I grew up in Howland. They had as much influence on my decision to go to the Air Force Academy and do something with my life as anybody.”

“They taught me to assume those leadership roles. They are woefully underpaid and under-appreciated, and I’ll recognize them in my own way as I’m able to track them down,” Harrison said.

Career

At his retirement ceremony on July 1, Harrison was presented an American flag that was flown over the Pentagon on April 28, the anniversary of Desert One; over the Air Force Academy on June 2, the anniversary of his graduation there; and over the Capitol Building on July 1, his official retirement date.

During his career, Harrison commanded at the squadron and group levels and held numerous staff positions in the United States and overseas.

His last assignment was at the Pentagon as the chief of the Ranges and Airspace Division and director of Operations and Training, deputy chief of staff of Air and Space Operations.

Harrison has logged 3,900 flying hours in various aircraft. He was promoted to Colonel in November 1997 and has numerous awards and decorations.

He received a bachelor’s degree in business management from the academy, a master’s in aeronautical science from Embry Riddle Aeronautical University and also attended the Armed Forces Staff College. He is the son of Lois Harrison and the late Donald Harrison.

His sister, Leslie, lives with their mother in Howland, and his brother, George, is in Fort Myers, Florida.

While at Howland High School, where he graduated ninth in a class of 388, he earned varsity letters in baseball, football and basketball and participated in track and field.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard