In Honored Memory of “The Lost Platoon”

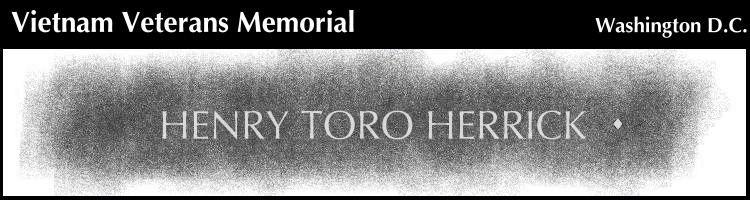

Henry Toro Herrick was born on August 31, 1941 and joined the Armed Forces while in Laguna Beach, California.

He served as a infantry officer in the United States Army. In one year of service, he attained the rank of Second Lieutenant (O1). He began a tour of duty on August 18, 1965.

On November 15, 1965, at the age of 24, Henry Toro Herrick perished in the service of our country in South Vietnam.

Lieutenant Herrick was buried at Arlington National Cemetery on 3 December 1965 (Section 37, Grave 3035).

One reviewer, for instance, took umbrage with, among other things, the line in the movie where a dying Lieutenant Henry Herrick softly and proudly tells his buddies, “I’m glad I could die for my country.” The reviewer saw this as offensively maudlin and false. But Sergeant Ernie Savage, who was there at Herrick’s side amidst the blood and gore, says it is true. According to Savage, “He was lying beside me on the hill and he said: ‘If I have to die, I’m glad to give my life for my country.’” And we should thank God that there are still men like Lt. Herrick, like Nathan Hale, who hold those “maudlin” sentiments; that is what has kept us free.

Lieutenant Herrick was hit by a bullet which entered his hip, coursed through his body, and went out through his right shoulder. As he lay dying, the lieutenant continued to direct his perimeter defense, and in his last few moments he gave his signal operation instructions book to Staff Sergeant Carl L. Palmer, his platoon sergeant, with orders to burn it if capture seemed imminent. He told Palmer to redistribute the ammunition, call in artillery fire, and at the first opportunity try to make a break for it. Sergeant Palmer, himself already slightly wounded, had no sooner taken command than he too was killed.

The 2d Squad leader took charge. He rose on his hands and knees and mumbled to no one in particular that he was going to get the platoon out of danger. He had just finished the sentence when a bullet smashed into his head. Killed in the same hail of bullets was the forward observer for the 81-mm. mortar. The artillery reconnaissance sergeant, who had been traveling with the platoon, was shot in the neck. Seriously wounded, he became delirious and the men had difficulty keeping him quiet.

Sergeant Savage, the 3d Squad leader, now took command. Snatching the artilleryman’s radio, he began calling in and adjusting artillery fire. Within minutes he had ringed the perimeter with well-placed concentrations, some as close to the position as twenty meters. The fire did much to discourage attempts to overrun the perimeter, but the platoon’s position still was precarious. Of the 27 men in the platoon, 8 had been killed and 12 wounded, leaving less than a squad of effectives.

After the first unsuccessful attempt to rescue the isolated force, Company B’s two remaining platoons had returned to the creek bed where they met Captain Herren. Lieutenants Deveny and Deal listened intently as their company commander explained that an artillery preparation would precede the two-company assault that Colonel Moore planned. Lieutenant Riddle, the company’s artillery forward observer, would direct the fire. The platoons would then advance abreast from the dry creek bed.

The creek bed was also to serve as a line of departure for Captain Nadal’s company. The Company A soldiers removed their packs and received an ammunition resupply in preparation for the move. Aside from the danger directly in front of him, Nadal believed the greatest threat would come from the left, toward Chu Pong, and accordingly he planned to advance with his company echeloned in that direction, the 2d Platoon leading, followed by the 1st and 3d in that order. Since he was unsure of the trapped platoon’s location, Captain Nadal decided to guide on Company B. If he met no significant resistance after traveling a short distance, he would shift to a company wedge formation. Before embarking on his formidable task, Nadal assembled as many of his men as possible in the creek bed and told them that an American platoon was cut off, in trouble, and that they were going after it. The men responded enthusiastically.

Preceded by heavy artillery and aerial rocket fire, most of which fell as close as 250 meters in front of Company B, which had fire priority, the attack to reach the cutoff platoon struck out at 1620, Companies A and B abreast. Almost from the start it was rough going. So close to the creek bed had the enemy infiltrated that heavy fighting broke out almost as soon as the men left it. Well camouflaged, their khaki uniforms blending in with the brownish-yellow elephant grass, the North Vietnamese soldiers had also concealed themselves in trees, burrowed into the ground to make “spider” holes, and dug into the tops and sides of anthills.

The first man in his company out of the creek bed, Captain Nadal had led his 1st and 2d Platoons only a short distance before they encountered the enemy. The 3d Platoon had not yet left the creek bed. 2d Lt. Wayne O. Johnson fell, seriously wounded, and a few moments later a squad leader yelled that one of his team leaders had been killed.

Lieutenant Marm’s men forged ahead until enemy machine gun fire, which seemed to come from an anthill thirty meters to their front, stopped them. Deliberately exposing himself in order to pinpoint the exact enemy location, Marm fired an M72 antitank round at the earth mound. He inflicted some casualties, but the enemy fire still continued. Figuring that it would be a simple matter to dash up to the position and toss a grenade behind it, he motioned to one of his men to do so. At this point the noise and confusion was such that a sergeant near him interpreted the gesture as a command to throw one from his position. He tossed and the grenade fell short. Disregarding his own safety, Marm dashed quickly across the open stretch of ground and hurled the grenade into the position, killing some of the enemy soldiers behind it and finishing off the dazed survivors with his M16. Soon afterward he took a bullet in the face and had to be evacuated. (For this action he received the Medal of Honor.)

Captain Nadal watched the casualties mount as his men attempted to inch forward. All of his platoon leaders were dead or wounded and his artillery forward observer had been killed. Four of his men were killed within six feet of him, including Sfc. Jacke Gell, his communications sergeant, who had been filling in as a radio operator. It was a little past 1700 and soon it would be dark. Nadal’s platoons had moved only 150 meters and the going was tougher all the time. Convinced that he could not break through, he called Colonel Moore and asked permission to pull back. The colonel gave it.

Captain Herren’s situation was little better than Captain Nadal’s. Having tried to advance from the creek bed by fire and maneuver, Herren too found his men engaged almost immediately and as a result had gained even less ground than Company A. Understrength at the outset of the operation, Herren had incurred thirty casualties by 1700. Although he was anxious to reach his cutoff platoon, he too held up his troops when he monitored Captain Nadal’s message.

Colonel Moore had little choice as to Captain Nadal’s request. The battalion was fighting in three separate actions-one force was defending X-RAY, two companies were attacking, and one platoon was isolated. To continue under these circumstances would be to risk the battalion’s defeat in detail if the enemy discovered and capitalized on Moore’s predicament. The forces at X-RAY were liable to heavy attack from other directions, and to continue to push Companies A and B against so tenacious an enemy was to risk continuing heavy casualties. The key to the battalion’s survival, as Moore saw it, was the physical security of X-RAY itself, especially in the light of what the first prisoner had told him about the presence of three enemy battalions. Moore decided to pull his forces back, intending to attack again later that night or early in the morning or to order the platoon to attempt to infiltrate back to friendly lines.

But the move was not easy to make. Because of the heavy fighting, Company A’s 1st Platoon had trouble pulling back with its dead and wounded. Captain Nadal committed the 3d Platoon to help relieve the pressure and assist with the casualties. Since he had lost his artillery forward observer, he requested through Colonel Moore artillery smoke on the company to screen its withdrawal. When Moore relayed the request, the fire direction center replied that smoke rounds were not available. Recalling his Korean War experience, Moore approved the use of white phosphorus instead. It seemed to dissuade the enemy; fire diminished immediately thereafter. The success of the volley encouraged Nadal to call for another, which had a similar effect. Miraculously, in both instances, no friendly troops were injured, and both companies were able to break away.

By 1705 the 2d Platoon and command group of Company B, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, were landing in X-RAY. Amidst cheers from the men on the ground, Capt. Myron Diduryk climbed out of the lead helicopter, ran up to Colonel Moore, and saluted with a “Gerry Owen, sir!” Colonel Moore briefed Diduryk on the tactical situation and then assigned him the role of battalion reserve and instructed him to be prepared to counterattack in either Company A, B, or C sector, with emphasis on the last one. An hour or so later, concerned about Company C’s having the lion’s share of the perimeter, Colonel Moore attached Diduryk’s 2d Platoon to it.

Captain Diduryk’s 120-man force was coming to the battle as well prepared as the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, troops already there. Each rifleman had 15 to 20 magazines, and every M60 machine gun crew carried at least 4 boxes of ball ammunition. The 40-mm. grenadiers had 30 to 40 rounds each, and every man in the company carried at least 1 fragmentation grenade. In addition to a platoon-size basic load ammunition supply, Diduryk had two 81-mm. mortars and forty-eight high-explosive rounds.

When 2d Lt. James L. Lane, leader of the 2d Platoon, Company B, reported to Company C with his platoon for instructions, Captain Edwards placed him on the right flank of his perimeter where he could link up with Company A. Edwards directed all the men to dig prone shelters. Other than for close-in local security, Edwards established no listening posts. The thick elephant grass would cut down on their usefulness, and the protective artillery concentrations that he planned within a hundred meters of his line would endanger them.

Rather than dig in, Company A took advantage of the cover of the dry creek bed. Captain Nadal placed all his platoons in it, except for the four left flank positions of his 3d Platoon, which he arranged up on the bank where they could tie in with Company C.

Company B elected not to use the creek bed. Instead, Captain Herren placed his two depleted platoons just forward of it, along 150 meters of good defensive terrain, an average of five meters between positions, with his command post behind them in the creek bed. He began immediately to register his artillery concentrations as close as possible to his defensive line and ordered his men to dig in.

Company D continued to occupy its sector of the perimeter without change.

By 1800 all of Company B, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, had landed. A half hour later Colonel Moore, figuring that the reconnaissance platoon was a large enough reserve force, readily available and positioned near the anthill, changed Captain Diduryk’s mission, directing him to man the perimeter between Companies B and D with his remaining two platoons. 2d Lt. Cyril R. Rescorla linked his 1st Platoon with Company B, while 2d Lt. Albert E. Vernon joined his flank with Company D on his left. Diduryk placed his two 81-mm. mortars with the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, and allowed some of the crew to man the perimeter. Soon his men were digging in, clearing fields of fire, and adjusting close-in concentrations.

Except for completing registration of artillery and mortar fire, Colonel Moore had organized his battalion perimeter by 1900. Fighting had long since died down to the tolerable level of sporadic sniper fire, and as night came on the last of the dead and wounded were being airlifted to FALCON from the collecting point in the vicinity of the battalion command post, near the anthill. Just before dark a resupply of much needed ammunition, water, medical supplies, and rations was flown in. The aid station had been dangerously low on dexadrine, morphine, and bandages, and the water supply had reached such a critical stage at one point that a few soldiers had eaten C ration jam for its moisture content to gain relief from the heat. A two-ship zone for night landing was established in the northern portion of X-RAY. Although under enemy observation and fire, it was much less vulnerable than other sectors of X-RAY where most of the fighting had occurred.

At 1850 Colonel Moore radioed his S-3, Captain Dillon, to land as soon as possible with two more radio operators, the artillery liaison officer, the forward air controller, more small arms ammunition, and water. Except for refueling stops Dillon had been in the command helicopter above X-RAY continuously, monitoring the tactical situation by radio, relaying information to brigade headquarters, and passing on instructions to the rifle companies; the helicopter itself served as an aerial platform from which Captain Whiteside and Lieutenant Hastings directed the artillery fire and air strikes. In order to carry out Colonel Moore’s instructions, Dillon requested two helicopters from FALCON. By 2125 Dillon was nearing X-RAY from the south through a haze of dust and smoke. Just as his helicopter approached for touchdown, he glanced to the left and saw what appeared to be four or five blinking lights on the forward slopes of Chu Pong. The lights hovered and wavered in the darkness. He surmised that they were North Vietnamese troops using flashlights to signal each other while they moved, for he recalled how an officer from another American division had reported a similar incident two months earlier during an operation in Binh Dinh Province. Upon landing, Dillon passed this information on to Whiteside and Hastings as target data.

During the early hours of darkness, Colonel Moore, accompanied by his sergeant major, made spot visits around the battalion perimeter, talking to the men. Although his troops were facing a formidable enemy force and had suffered quite a few casualties, their morale was clearly high. Moore satisfied himself that his companies were tied in, mortars were all registered, an ammunition resupply system had been established, and in general his troops were prepared for the night.

During the evening the 66th North Vietnamese Regiment moved its 8th Battalion southward from a position north of the Ia Drang and charged it with the mission of applying pressure against the eastern sector of X-RAY. Field Front headquarters meanwhile arranged for movement of the H-15 Main Force Viet Cong Battalion from an assembly area well south of the scene of the fighting. The 32d Regiment had not yet left its assembly area, some twelve kilometers away, and the heavy mortar and antiaircraft units were still en route to X-RAY.

At intervals during the night, enemy forces harassed and probedthe battalion perimeter in all but the Company D sector, and in each instance well-placed American artillery from FALCON blunted the enemy’s aggressiveness. Firing some 4,000 rounds, the two howitzer batteries in that landing zone also laced the fingers and draws of Chu Pong where the lights had been seen. Tactical air missions were flown throughout the night.

The remnants of Sergeant Savage’s isolated little band meanwhile continued to be hard pressed. Three times the enemy attacked with at least a reinforced platoon but were turned back by the artillery and the small arms fire of the men in the perimeter, including some of the wounded. Spec. 5 Charles H. Lose, the company senior medical aidman (whom Captain Herren had placed with the platoon because of a shortage of medics), moved about the perimeter, exposed to fire while he administered to the wounded. His diligence and ingenuity throughout the day and during the night saved at least a half-dozen lives; having run out of first-aid packets as well as bandages from his own bag, he used the C ration toilet tissue packets most of the men had with them to help stop bleeding. Calm, sure, and thoroughly rofessional, he brought reassurance to the men.

Before the second attack, which came at 0345, bugle calls were heard around the entire perimeter. Some sounds seemed to come from Chu Pong itself, 200 to 400 meters distant. Sergeant Savage could even hear enemy soldiers muttering softly to each other in the sing-song cadence of their language. He called down a 15-minute artillery barrage to saturate the area and followed it with a tactical air strike on the ground just above the positions. Executed under flagship illumination, the two strikes in combination broke up the attack. The sergeant noted that the illumination exposed his position and it was therefore not used again that night.

A third and final attack came over an hour later and was as unsuccessful as the previous two. Sergeant Savage and his men, isolated but still holding throughout the night, could hear and sometimes see the enemy dragging off his dead and wounded.

At brigade headquarters, Colonel Brown continued to assess the significance of the day’s activities. Pleased that the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, had been able to hold its own against heavy odds, and with moderate casualties, he was convinced that the fight was not yet over. He radioed General Kinnard for another battalion, and Kinnard informed him that the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry, would begin arriving at brigade headquarters the following morning.

Having decided much earlier to try again for the third time to reach the isolated platoon and at the same time to secure the perimeter, Colonel Moore was ready by the next morning. Both he and his S-3 felt that the main enemy effort would be against theplatoon. This time he intended to use three rifle companies instead of two. Since Captain Herren’s men were most familiar with the ground, he planned to reinforce Company B with a platoonfrom Company A and to use Company B as the lead force again. Colonel Moore and his command group were to follow Herren’s force. Companies A and C were to follow behind on the right and left, respectively, protecting the flanks and prepared to assist the main effort on order. The S-3, Captain Dillon, was to stay behind with the remainder of the battalion at the perimeter, ready to command it as a reserve force if necessary.

Ten minutes after first light, Colonel Moore directed all company commanders to meet him at the Company C command post where he would discuss final plans and view the attack route with them. He also told them to patrol forward and to the rear of their perimeter positions, looking for possible snipers or infiltrators that might

have closed in during the night.

Upon receiving these instructions, Captain Edwards of Company C radioed his platoon leaders and told them to send at least squadsize forces from each platoon out to a distance of 200 meters. No sooner had they moved out when heavy enemy fire erupted, shattering the morning stillness. The two leftmost reconnaissance elements, those of the 1st and 2d Platoons, took the brunt of the fire, which came mainly from their front and left front. They returned it and began pulling back to their defensive positions. Well camouflaged, and in some cases crawling on hands and knees, the North Vietnamese pressed forward. In short order the two reconnaissance parties began to suffer casualties, some of them fatal, while men in each of the other platoons were hit as they attempted to move forward to assist.

When he heard the firing, Captain Edwards immediately attempted to raise both the 1st and 2d Platoons on the radio for a situation report, but there was no answer; each platoon leader had accompanied the reconnaissance force forward. He called Lieutenant Lane, the attached platoon leader from Company B, 2d Battalion, and his 3d Platoon leader, 2d Lt. William W. Franklin, and was relieved to discover that most of their forces had made it back to the perimeter unscathed; a few were still attempting to help the men engaged with the enemy.

From his command post, Edwards himself could see fifteen to twenty enemy soldiers 200 meters to his front, moving toward him. He called Colonel Moore, briefed him on the situation, and requested artillery fire. Then he and the four others in his command group began firing their M16’s at the advancing enemy. Edwards called battalion again and requested that the battalion reserve be committed in support.

Colonel Moore refused, for both he and Captain Dillon were still unconvinced that this was the enemy’s main effort. They expected a strong attack against the isolated platoon and wanted to be prepared for it. Also, from what they could hear and see, Edwards’ company appeared to be holding on, and they had given him priority of fires.

The situation of Company C grew worse, however, for despite a heavy pounding by artillery and tactical air and despite heavy losses the enemy managed to reach the foxhole line. Captain Edwards attempted to push Franklin’s 3d Platoon to the left to relieve some of the pressure, but the firing was too heavy. Suddenly two North Vietnamese soldiers appeared forty meters to the front of the command post. Captain Edwards stood up and tossed a fragmentation grenade at them, then fell with a bullet in his back.

At 0715, seriously wounded but still conscious, Edwards asked again for reinforcements. This time Moore assented; he directed Company A to send a platoon. Company C’s command group was now pinned down by an enemy automatic weapon that was operating behind an anthill just forward of the foxhole line. 2d Lt. John W. Arrington, Edwards’ executive officer, had rushed forward from the battalion command post at Colonel Moore’s order when Edwards was wounded. As Arrington lay prone, receiving instructions from Captain Edwards, he was shot in the chest. Lieutenant Franklin, realizing that both his commanding officer and the executive officer had been hit, left his 3d Platoon position and began to crawl toward the command group. He was hit and wounded seriously.

Almost at the same time that the message from Edwards asking for assistance reached the battalion command post, the enemy also attacked the Company D sector in force near the mortar emplacements. The battalion was now being attacked from two different directions.

As soon as Captain Nadal had received the word to commit a platoon, he had pulled his right flank platoon, the 2d, for the mission since he did not want to weaken that portion of the perimeter nearest Company C. He ordered his remaining platoon to extend to the right and cover the gap. The 2d Platoon started across the landing zone toward the Company C sector. As it neared the battalion command post, moving across open ground, it came under heavy fire that wounded two men and killed two. The platoon deployed on line, everyone prone, in a position just a few meters behind and to the left of the 3d Platoon of Company A’s left flank and directly behind Company C’s right flank. The force remained where it had beenstopped. It was just as well, for in this position it served adequately as a backup reserve, a defense in depth against any enemy attempt to reach the battalion command post.

The heavy fighting continued. At 0745 enemy grazing fire was crisscrossing X-RAY, and at least twelve rounds of rocket or mortar fire exploded in the landing zone. One soldier was killed near the anthill, others were wounded. Anyone who moved toward the Company C sector drew fire immediately. Still the men fought on ferociously. One rifleman from Company D, who during the fighting had wound up somehow in the Company C sector, covered fifty meters of ground and from a kneeling position shot ten to fifteen North Vietnamese with his M16.

Colonel Moore alerted the reconnaissance platoon to be prepared for possible commitment in the Company D or Company C sector. Next, he radioed Colonel Brown at brigade headquarters, informed him of the situation, and requested another reinforcing company. Colonel Brown approved the request and prepared to send Company A, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, into the landing zone as soon as the intensity of the firing diminished.

At 0755 Moore directed all units to throw colored smoke grenades so that ground artillery, aerial rocket artillery, and tactical air observers could more readily see the perimeter periphery, for he wanted to get his fire support in as close as possible. As soon as the smoke was thrown, supporting fires were brought in extremely close. Several artillery rounds landed within the perimeter, and one F-105 jet, flying a northwest-southeast pass, splashed two tanks of napalm into the anthill area, burning some of the men, exploding M16 ammunition stacked in the area, and threatening to detonate a pile of hand grenades. While troops worked to put out the fire, Captain Dillon rushed to the middle of the landing zone under fire and laid out a cerise panel so that strike aircraft could better identify the command post.

Despite the close fire support, heavy enemy fire continued to lash the landing zone without letup as the North Vietnamese troops followed their standard tactic of attempting to mingle with the American defenders in order to neutralize American fire support. A medic was killed at the battalion command post as he worked on one of the men wounded during the napalm strike. One of Colonel Moore’s radio operators was struck in the head by a bullet; he was unconscious for a half hour, but his helmet had saved his life.

By 0800 a small enemy force had jabbed at Company A’s left flank and been repulsed, but Company D’s sector was seriously threatened. Mortar crewmen were firing rifles as well as feeding rounds into their tubes when a sudden fusillade destroyed one of themortars. The antitank platoon was heavily engaged at the edge of the perimeter. With the battalion under attack from three sides now, Colonel Moore shifted the reconnaissance platoon toward Company D to relieve some of the pressure there. He radioed Colonel Brown for the additional company and alerted Company B, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, for action. He would have Company B on call until the battalion’s Company A could put down in the landing zone.

Moore ordered Captain Diduryk to assemble his command group and his 1st Platoon at the anthill. Since he had already committed his 2d Platoon to Company C the previous night, Diduryk had left only the 3d Platoon to occupy his entire sector of the perimeter. He told the platoon leader, Lieutenant Vernon, to remain in position until relieved. Diduryk’s 1st Platoon had lost one man wounded and one killed from the extremely heavy grazing fire and had not yet even been committed.

By 0900 the volume of combined American fires began to take its toll; enemy fire slacked. Ten minutes later, elements of Company A, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, landed. Colonel Moore directed the company commander, Capt. Joel E. Sugdinis, to occupy Diduryk’s original sector, which he did after co-ordinating with Diduryk.

By 1000 the enemy’s desperate attempts to overwhelm the perimeter had failed and attacks ceased. Only light sniper fire continued. A half hour later Diduryk’s company joined Lieutenant Lane’s platoon in the Company C sector. Diduryk’s force was augmented by the 3d Platoon of Company A, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, which had rushed there immediately upon landing. Colonel Moore elected to allow it to remain.

Meanwhile, less than three kilometers southeast of the fighting, additional reinforcements were en route to X-RAY. Having departed Landing Zone VICTOR earlier that morning, Colonel Tully’s 2d Battalion, 5th Cavalry, was moving on foot toward the sound of the firing.

Because of the scarcity of aircraft on 13 November as well as the dispersion of his companies over a relatively large area, Colonel Tally had been able to send only two of his companies into VICTOR before dark on the 14th. At that, it had been a major effort to get one of them, Company C, picked up and flown to VICTOR, so dense was the jungle cover. In clearing a two-helicopter pickup zone, the soldiers of Company C had used over thirty pounds of plastic explosive and had broken seventeen intrenching tools.

By the early morning hours of the 15th, Colonel Tully nevertheless had managed to assemble his three rifle companies in accordance with Colonel Brown’s instructions. The task force moved out at 0800, Companies A and B abreast, left and right, respectively, with Company C trailing Company A. Colonel Tully used this formation, heavy on the left, because of the Chu Pong threat. He felt that if the enemy struck again it would be from that direction. He had no definite plan as to what he would do when he arrived at X-RAY other than reinforce. Details would come later.

Shortly after the fighting died down at X-RAY, enemy automatic weapons fire pinned down the two lead platoons of Company A, 2d Battalion, 5th Cavalry, as they approached from the east, 800 meters from the landing zone. The North Vietnamese were in trees and behind anthills. The company commander, Capt. Larry T. Bennett, promptly maneuvered the two lead platoons, which were in a line formation, forward. Then he swung his 3d Platoon to the right flank and pushed ahead; his weapons platoon, which had been reorganized into a provisional rifle platoon, followed behind as reserve. The men broke through the resistance rapidly, capturing two young and scared North Vietnamese armed with AK47 assault rifles.

Soon after midday lead elements reached X-RAY. Colonel Moore and Colonel Tully co-ordinated the next move, agreeing that because they were in the best position for attack and were relatively fresh and strong upon arriving at the landing zone, Companies A and C, 2d Battalion, 5th Cavalry, would participate in the effort to reach the cutoff platoon. Company B, 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, would take the lead since Herren knew the terrain between X-RAY and the isolated platoon. Moore would receive Company B, 2d Battalion, 5th Cavalry, into the perimeter and would remain behind, still in command, while Colonel Tully accompanied the attack force. The incoming battalion’s mortar sections were to remain at X-RAY and support the attack.

Colonel Tully’s coordination with Captain Herren was simple enough. Tully gave Herren the appropriate radio frequencies and call signs, told him where to tie in with his Company A, and instructed him to move out when ready. At 1315, preceded by artillery and aerial rocket strikes, the rescue force started out, Herren’s company on the right, Company A, 2d Battalion, 5th Cavalry, on the left.

Fifteen minutes after the relief force had left the perimeter, Colonel Moore directed all units to police the battlefield to a depth of 300 meters. They soon discovered the heavy price the enemy had paid for his efforts: enemy bodies littered the area, some stacked behind anthills; body fragments, weapons, and equipment were scattered about the edge of the perimeter; trails littered with bandages told of many bodies dragged away.

The cost had also been heavy for the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, which had lost the equivalent of an American rifle platoon. The bodies of these men lay amongst the enemy dead and attested to the intensity of the fight. One rifleman of Company C lay with his hands clutched around the throat of a dead North Vietnamese soldier. Company C’s 1st Platoon leader died in a foxhole surrounded by five enemy dead.

The relief party, meanwhile, advanced cautiously, harassed by sporadic sniper fire to which the infantrymen replied by judiciously calling down artillery fire. As they neared Sergeant Savage’s platoon, lead troops of Captain Herren’s company found the captured M60 machine gun, smashed by artillery fire. Around it lay the mutilated bodies of the crew, along with the bodies of successive North Vietnamese crews. They found the body of the M79 gunner, his .45-caliber automatic still clutched in his hand.

A few minutes later, the first men reached the isolated platoon; Captain Herren stared at the scene before him with fatigue-rimmed eyes. Some of the survivors broke into tears of relief. Through good fortune, the enemy’s ignorance of their predicament, Specialist Lose’s first-aid knowledge, individual bravery, and, most important of all, Sergeant Savage’s expert use of artillery fire, the platoon had incurred not a single additional casualty after Savage had taken command the previous afternoon. Each man still had adequate ammunition.

Colonel Tully did not make a thorough search of the area, for now that he had reached the platoon his concern was to evacuate the survivors and casualties to X-RAY in good order. Accordingly, he surrounded the position with all three companies while Captain Herren provided details of men to assist with the casualties. The task was arduous, for each dead body and many of the wounded required at least a four-man carrying party using a makeshift poncho litter.

As he walked the newly established outer perimeter edge to check on the disposition of one of his platoons, Captain Bennett, the commander of Company A, 2d Battalion, 5th Cavalry, fell, severely wounded by a bullet in his chest fired at close range by a hidden North Vietnamese sniper. A thorough search for the enemy rifleman proved fruitless, and Colonel Tully directed his force to return to X-RAY. With Herren’s company in single file and the casualties and Tully’s units on either-flank, the rescue force arrived at the landing zone without further incident.

Colonel Moore now redisposed his troops. Since he had two battalions to employ, he worked out an arrangement with Colonel Tully that allowed him to control all troops in the perimeter. He took Company D, minus the mortar platoon, off of the line and replaced it with Colonel Tully’s entire battalion. Tully’s force also occupied portions of the flanking unit sectors. The wounded and dead were evacuated and everyone dug in for the night.

That evening at brigade headquarters Colonel Brown again conferred with General Kinnard, who told Brown that the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, would be pulled out on the 16th and sent to Camp Holloway just outside Pleiku for two days of rest and reorganization.

Although the North Vietnamese had suffered heavy casualties, not only from their encounter with the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, but also as a result of a B-52 strike on Chu Pong itself that afternoon, they had not abandoned the field entirely. Sporadic sniper fire continued at various points along the perimeter during the early part of the night. The moon was out by 2320 in a cloudless sky. American artillery fired continuously into areas around the entire perimeter and on Chu Pong where secondary explosions occurred during the early evening. At 0100 five North Vietnamese soldiers probed the Company B, 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, sector; two were killed and the others escaped. Three hours later, a series of long and short whistle signals were heard from the enemy, and a flurry of activity occurred in front of Company B, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry. Trip flares were ignited and anti-intrusion alarms sprung, some as far out as 300 meters. At 0422 Diduryk’s attached Company A platoon leader, 2d Lt. William H. Sisson, radioed that he could see a group of soldiers advancing toward his positions. He was granted permission to fire and at the same time his platoon was fired on by the enemy. In less than ten minutes Diduryk was under attack along his entire sector by at least a company-size force. His company met the attack with a fusillade of fire from individual weapons, coupled with the firepower of four artillery batteries and all available mortars. Calling for point-detonating and variable time fazes, white phosphorus, and high-explosive shells, Diduryk’s forward observer, 1st Lt. William L. Lund, directed each battery to fire different defensive concentrations in front of the perimeter, shifting the fires laterally and in depth in 100-meter adjustments. This imaginative effort, along with illumination provided by Air Force flareships, proved highly effective. Enemy soldiers nevertheless attempted to advance during the brief periods of darkness between flares and in some cases managed to get within five to ten meters of the foxhole line, where they were halted by well-aimed hand grenades and selective firing.

At 0530 the enemy tried again, this time shifting to the southwest, attacking the 3d Platoon and some left flank positions of the 2d Platoon. This effort, as well as another launched an hour later against the 1st Platoon’s right flank, was also repulsed.

During the firelight, the Company B executive officer, radio operators, and troops from the reconnaissance platoon of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, made three separate ammunition resupply runs under fire to the anthill. At one point the supply of M79 ammunition dropped to such a dangerously low level that Diduryk restricted its use to visible targets, especially enemy crew-served weapons and troop concentrations.

By dawn of the 16th the enemy attack had run its course. Diduryk’s company had only six men slightly wounded, while piles of enemy dead in front of the positions testified to the enemy’s tactical failure.

Still concerned with possible enemy intentions and capabilities and no doubt wary because of what had happened to Company C on the previous morning’s sweep, Colonel Moore directed all companies to spray the trees, anthills, and bushes in front of their positions to kill any snipers or other infiltrators-a practice that the men called a “mad minute.” Seconds after the firing began, an enemy platoon-size force came into view 150 meters in front of Company A, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, and opened fire at the perimeter. An ideal artillery target, the attacking force was beaten off in twenty minutes by a heavy dose of high-explosive variable time fire. The “mad minute” effort proved fruitful in other respects. During the firing one North Vietnamese soldier dropped from a tree, dead, immediately in front of Captain Herren’s command post. The riddled body of another fell and hung upside down, swinging from the branch to which the man had tied himself in front of Diduryk’s leftmost platoon. An hour later somebody picked off an enemy soldier as he attempted to climb down a tree and escape.

Company C, 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, and the reconnaissance platoon meanwhile made a detailed search of the interior of X-RAY itself. There were three American casualties unaccounted for, and Colonel Moore was still concerned about infiltrators. The search turned up nothing.

An hour later Moore considered it opportune to push out from the perimeter on a co-ordinated search and to sweep out to 500 meters. The move commenced at 0955. After covering fifty to seventy-five meters, Company B, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, platoons met a large volume of fire, including hand grenades thrown by enemy wounded still lying in the area. Diduryk quickly lost a weapons squad leader killed and nine other men wounded, including the 2d Platoon leader and platoon sergeant. Under artillery cover, he withdrew his force to the perimeter. Colonel Moore and Lieutenant Hastings, the forward air controller, joined him. A few minutes later tactical air, using a variety of ordnance that included rockets, cannon, napalm, cluster bomb units, white phosphorus, and high explosive, blasted the target area. The strike ended with the dropping of a 500-pound bomb that landed only twenty-five meters from the 1st Platoon’s positions.

The sweep by Company B, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, began again, this time using fire and maneuver behind a wall of covering artillery fire and meeting scattered resistance which was readily eliminated. Twenty-seven North Vietnamese were killed. The sweep uncovered the three missing Americans, all dead. The area was littered with enemy dead, and many enemy weapons were collected.

By 0930 the lead forces of the remainder of the 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, reached X-RAY, and an hour later Colonel Moore received instructions to prepare his battalion, along with Company B, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, and the 3d Platoon, Company A, 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, for the move to Camp Holloway. The remainder of the 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, and 2d Battalion, 5th Cavalry, were to be left behind to secure the perimeter. Moore did not want to leave, however, without another thorough policing of the battle area, particularly where Company C had been attacked on the morning of the 15th. Captain Diduryk therefore conducted a lateral sweep without incident to a distance of 150 meters.

As the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, began its move to Camp Holloway, the casualties with their equipment, as well as the surplus supplies, were also evacuated. Captured enemy equipment taken out included 57 Kalashnikov AK47 assault rifles, 54 Siminov SKS semiautomatic carbines with bayonets, 17 Degtyarev automatic rifles, 4 Maxim heavy machine guns, 5 model RPG2 antitank rocket launchers, 2 81-mm. mortar tubes, 2 pistols, and 6 medic’s kits.

Great amounts of enemy weapons and equipment had been previously destroyed elsewhere in the battle area, and Moore arranged with the commanding officer of the 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, to destroy any enemy materiel left behind at X-RAY. Included were 75 to 100 crew-served and individual weapons, 12 antitank rounds, 300 to 400 hand grenades, an estimated 5,000 to 7,000 small arms rounds, and 100 to 150 entrenching tools.

American casualties, attached units included, were 79 killed, 121 wounded, and none missing. Enemy losses were much higher and included 634 known dead, 581 estimated dead, and 6 prisoners.

January 8, 1999

Ia Drang Valley

Vietnam battles test viability of helicopter-assault concept

by S. H. Kelly

Pentagram staff writer

When the 1st Cavalry Division went into South Vietnam’s Ia Drang Valley November 14, 1965, on the unit’s first major operation since arriving in the country, they went in response to a brief order from Corps Commander Major General Stanley “Swede” Larsen — “Find the enemy and go after him.”

Intelligence had placed elements of at least two North Vietnamese Army regiments, and 1st Cav. elements had had a few clashes with small NVA forces earlier in the month.

Lt. Col. Harold G. Moore, commander of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, had picked for a landing zone a clearing near the eastern slope of the Chu Pong Massif — a mountain mass that straddled the South Vietnam-Cambodia border and stretched about five miles into Vietnam’s Central Highlands.

The helicopter assault into Landing Zone X-Ray would be made by companies A, B, C and D of Moore’s battalion, and Co. B, 2nd Bn., 7th Cav., which was attached for the operation. Sixteen UH1 (Huey) helicopters from Co. A, 229th Assault Helicopter Bn., each capable of carrying four to eight combat-ready troops into battle would be used. The less fuel on board, the greater payload each could carry.

Fuel load thus limited the first lift to 80 troops, but succeeding lifts could carry more as the helicopters burned off fuel. The battalion had about 200 fewer men than its authorized 767-man strength.

Each man was to carry two canteens of water, one C-ration meal, weapon and basic load of ammunition (300 rounds for riflemen), two hand grenades and as much extra ammo as he could carry. Grenadiers armed with M-79 grenade launchers were to each carry at least 36 rounds of 40mm ammunition, and each squad was to have at least two light anti-tank weapons.

Initial fire support would come from two nearby 105mm howitzer batteries (12 guns total) and an array of Huey’s modified to fire aerial rocket artillery or machine guns.

Following artillery and rocket barrages on X-Ray, Moore accompanied B-1/7 on the first lift into the landing zone, hitting the LZ at 10:48 a.m. Nov. 14. The troops immediately fanned through the elephant grass in to the “lightly wooded” area and formed a defense perimeter, with fire teams moving deeper into the woods to make

sure the area was clear. Moore and his command group set up in some scrub brush at the northeastern edge of the landing zone. Although the landings had been observed by enemy leaders, an attack was delayed by the dispersal of the three enemy battalions. The delay allowed a second lift of 1/7 Cav. troops into the perimeter at

11:20 a.m. and a third at 12:10.

The first rifle shots rang out at 12:15, and the troops of the two companies now on the ground moved deeper into the brush on the three sides of the “football-field-size” landing zone nearest the massif.

With Co. B on orders to develop the contact at Chu Pong’s base, its platoons moved deeper into the brush, and the incoming fire increased. Within a half hour, the Moore’s battalion was in a full-blown firefight.

As the NVA troops came down the massif, Co. B’s 1st Platoon spotted a column coming down the mountain and took it under fire. They had no knowledge of the size of the force, but in moments the platoon was under attack by 30 or 40 NVA troops that hit both of the platoon’s flanks.

To the right (northeast) of 1st Platoon, 2nd Platoon was also taking fire, and the platoon leader reported he had spotted a squad of enemy soldiers and was in pursuit. Distancing themselves from the main body, the 2nd Platoon was soon cut off in the brush and surrounded by an enemy force of 40 to 50 NVA soldiers.

The 29-man platoon lost nine dead and 13 wounded in the battle — all within the first 90 minutes, and would remain isolated from the remainder of the battalion until rescued by its parent company and companies A and C of the 5th Cavalry. The 2nd Platoon became known as “The Lost Platoon.” Among the dead would be the

platoon leader, 2nd Lt. Henry T. Herrick.

Enemy mortar and rocket fire had now entered the battle as a full 500-man NVA battalion fronted Company B. Lift helicopters continued bringing in battalion soldiers as Moore did his best by radio to maneuver elements of his force to where they would do the most good — his battalion command post now located at a seven-to-eight-foot termite mound.

By now, according to Moore in his book, the “snaps and cracks of the rounds passing nearby took on a distinctly different sound” from the early fire, “like a swarm of bees around our heads.”

The battalion aid station arrived aboard medical-evacuation helicopters with one of the troop lifts — three people out 13 authorized.

Moore, with only about half his battalion on the ground, had his operations officer, Capt. Gregory P. Dillon, call for fire support. Dillon brought in air strikes, “tube” artillery and aerial rocket artillery on the approaches to the perimeter from the mountain and between the U.S. force and the enemy in what Moore called a “blessed river of high-powered destruction.”

The strikes and artillery had to be placed carefully because of the fluidity of the battle lines and the fact that one platoon was cut off from the rest of the force.

About two hours into the battle, the first of three aircraft losses occurred. A World War II-vintage propeller-driven A-1E Skyraider piloted by Capt. Paul T. McClellan Jr. crashed after delivering a bomb load over the enemy.

The second aircraft was a helicopter lost later in the battle. The pilot, who had brought in a load of badly need ammunition, was trying to take off from the LZ with a load of prisoners and wounded when his craft was disabled. Another helicopter was disabled in the LZ when the pilot overflew enemy gunners.

Throughout the battle, attempts were made to link up with the lost platoon, but equally pressing was keeping the perimeter intact and holding the landing zone open. Helicopters using the LZ were taking automatic-weapons fire, but couldn’t fire suppression because of the nearness of the friendly troops. Still, they lingered on the ground to evacuate the wounded, the number of which were rapidly multiplying.

With dusk approaching, Moore led his force back into a tighter perimeter, and troops dug in as best they could — still under attack and using artillery support to keep the enemy at bay.

The day’s toll on companies A and B was 81 officers and men killed or wounded.

The 229th had been flying medical evacuation in addition to their troop and ammunition-hauling duties because, according to the 229th commander, the medical-evacuation-helicopter pilots refused to go into the “hot” LZ after the first flight.

Helicopters from the 229th picked up dead and wounded from X-Ray and flew them to secure “fire bases” where medical-evacuation helicopters would pick them up and transport them to medical facilities.

Pilots of the 229th, who had begun flying at 6 a.m., finally shut down their aircraft after 10 p.m.

One soldier equated the day’s battle to everything he had seen in the movies — hand-to-hand battle, grenades, bayonet thrusts, mortars, artillery, the works.

As darkness fell, NVA soldiers could be seen using lights for signaling devices, and U.S. observers called in artillery on the lights when they could. They also called in artillery to put “rings of steel” around X-Ray and the cut-off platoon.

The night degenerated into enemy probes on the LZ perimeter and attacks on the lost platoon — all repulsed by the defenders.

The NVA commander later said he had planned to launch a battalion-strength attack on X-Ray at 2 a.m., but the attack was disrupted by air strikes. That attack came about 6:30 a.m. the next day — just as Moore launched a three-company attempt to relieve the lost platoon. A patrol spotted the oncoming NVA force, and the battle resumed with 1/7th returning to the defense.

This time, however, some of the North Vietnamese had gotten too close for Moore to employ his artillery safely. Now the battle was face to face with U.S. soldiers, NCO and officer alike battling to hold their positions.

Moore’s air controller broadcast the code words “Broken Arrow,” which meant an American unit was in peril of being overrun. This call summoned support from all available aircraft in the country, and they were shortly on station “stacked” above the battle awaiting targets.

Even as the air support arrived, a Viet Cong battalion added its weight to the attack.

Two F-100 Super Saber jet fighters were among the support that orbited the LZ. When their turn came to release their loads, troops on the ground watched in horror as the lead plane dropped its two canisters of napalm on a direct line with a U.S. demolition squad. Had the trailing aircraft followed suit, its load would likely have fallen on the command group, but the forward air controller was able to get the pilot to abort his drop.

The napalm from the first plane hit some of the engineers and set some fires, but the fires were quickly extinguished. Although devastated by the accident, Moore requested a continuation of the air and artillery support, which continued to fall within friendly lines.

About 9:10 a.m. Co. A, 1st Bn., 7th Cav., was lifted into the perimeter, and the 2nd Bn., 5th Cav., commanded by Lt. Col. Bob Tully, was on its way to the rescue, traveling overland prepared for a fight. They got it when they were about 30 minutes’ march from the beleaguered battalion — about 800 yards east of the LZ.

The lead platoons were taken under fire by an NVA blocking, but using fire and maneuver, the battalion broke through the resistance and continued its advance. Finally, at 10 a.m., about the same time the relief column had been hit, the enemy force besieging the perimeter had begun to withdraw, leaving snipers to harass

Moore’s battalion. The lead elements of 2nd Bn., 5th Cav., walked into the LZ at about 11:45, and the siege was broken.

Moving across the LZ, two of Tully’s companies and the lost platoon’s parent company followed a helicopter-rocket barrage across the stretch of land between the LZ and the lost platoon, meeting no resistance. They did, however, spot enemy soldiers in the distance leaving the area. They did receive some sniper fire after reaching the platoon position.

The combined battalions spent the remainder of the day policing the battlefield, with Moore in the midst of the search. He was adamant that no U.S. soldier, dead or alive, be left unaccounted for. He had been informed that his battalion would be extracted by helicopter the next day.

Before dark the battalions were dug in for the night. The cavalry position received some small-arms and automatic-weapons fire and enemy probes during the night. At 4:22 a.m. 7th Bn., 66 NVA Regiment, attacked, but the first rush was beaten back in about 10 minutes. A second attack shortly thereafter was also beaten back by small-arms, howitzer and mortar fire as Air Force flare ships kept the battlefield illuminated.

A third and fourth enemy charge, at 5:03 and 5:50 a.m., respectively, met the same fate, as did the fifth charge at about 6:30. Finally, the NVA broke off the attack, and the retreating force was shredded by artillery fire.

A “mad minute,” everyone on the perimeter firing a magazine of ammunition into the brush and termite mounds at a given time, flushed a remaining 30 to 50 NVA out of hiding in preparation for another attack, and field artillery finished the attack before it could begin.

The combined force conducted another sweep of the battlefield, searching the bush on hands and knees for U.S. dead and injured until the last three bodies were found. When the head count and casualty reports added up to the proper number, Moore’s battalion was ready for evacuation.

While this search was underway, the 2nd Bn., 7th Cav., dispatched overland around 9:30 a.m. from LZ Columbus, about three miles east of X-Ray. The fresh battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Robert McDade, would replace Moore’s battalion at X-Ray — helping Tully’s battalion secure the battle area.

Helicopters began lifting 1/7th soldiers and Co. B of the 2/7th out of the LZ at 11:55 a.m., and the final lift, with Moore aboard, left around 3 p.m. The Hueys took the battalion to LZ Falcon, and they went from there by Chinook helicopter to Camp Holloway, near Pleiku.

For the night of the 16th, McDade and Tully’s battalions dug in on X-Ray had relative quiet. They took some rifle and mortar fire, but no assaults. Both battalions were, however, kept on 100-percent alert.

Arc Light B-52 bomber strikes were planned for Chu Pong and near its slopes for the next day, so the battalions would have to vacate the area beginning at 9 a.m.

They were to march northeast toward LZ Columbus, some three to four miles from X-Ray, with the 1/5th in the lead. McDade’s battalion was to break off during the march and head northwest to a “one-ship” LZ named Albany while Tully’s battalion continued to Columbus.

There is disagreement as to whether Albany was a destination for McDade’s battalion or simply an intermediate LZ.

As his battalion changed to the northwest, Co. A was in the lead, followed by Co. D, Co. C and Headquarters Co., with Co. A, 1st Bn., 5th Cav. bringing up the rear.

Most of the march to Albany was uneventful, but McDade’s force was under observation. NVA Lt. Col. Hoang Phuong later said he had reconnaissance groups watching the area, with some assigned to each potential LZ. He had immediately available two battalions, one newly arrived in South Vietnam, and the headquarters

elements of a third.

The terrain traveling from X-Ray varied from knee-high brush initially, to chest-high “elephant grass,” to triple-canopy jungle.

As the U.S. force neared Albany, the lead company captured two NVA soldiers after detecting sandal tracks and other enemy signs on the trail. It was about 11:40 a.m., somewhere around the same time Tully’s battalion closed on Columbus.

McDade halted his 550-yard-long column while he and his command group went to join Co. A in the interrogation of the prisoners. Up and down the column, the soldiers took a break — some opening up C-rations, some lighting up cigarettes and others just lolling around.

When McDade called the company commanders forward, most of the soldiers remained on the trail, while the tail-end company was ordered to deploy in a herringbone formation.

The commanders then made their way toward the head of the column with their radio operators, some taking with them various officers or NCOs. McDade and the commanders continued into a clearing — LZ Albany — and into a clump of trees. It was shortly after 1 p.m.

Suddenly a platoon of the lead company was taken under fire — fire that quickly escalated into a full-blown attack by the 8th Battalion, 66th NVA Regiment that had been bivouacked northeast of the LZ, on the right flank of the formation. The lead U.S. platoon had marched within about 200 yards of the 3rd Bn., 33rd NVA

Regiment, and that regiment’s headquarters and 1st Bn. joined the assault.

Attacking from the head and right side of the U.S. battalion, the combined NVA force pounded the column with small-arms, machine-gun and mortar fire.

Capt. George Forrest, commander of Co. A, 1/5th Cav., raced down the column and back to his company, losing both of his radio operators along the way. The three center companies, however, would have to go through the battle without their commanders — some without any senior officers.

Forrest recalled that as he passed through the column, some soldiers were still relaxed — not realizing immediately that they were under attack.

The column was quickly decimated — Co. A, battalion command group and company commanders at the head, a reasonably intact Co. A, 1/5th Cav. at the end, and small pockets of commanderless troops between, all fighting for survival.

At the head of the column, the battalion commander at first thought he was receiving friendly fire and was on the radio calling for his troops to cease fire, and others along the column were under the same impression.

The company at the head of the column tried to draw back to the trees where the command group was located, some soldiers dragging wounded comrades with them. Withdrawal was covered by a few machine-gunners.

Visible targets were available all around for those able to raise their heads without being shot. Enemy soldiers could be seen walking between the U.S. groups killing wounded or cut-off soldiers.

Separated as they were, many of the groups were without a means of communicating with other groups, and they were sometimes firing on each other.

Third Brigade Commander Col. Tim Brown orbited overhead in his command helicopter trying to find out by radio what was going on and how he could be of help — calling in artillery or reinforcements.

McDade’s forward artillery observer was asking for everything he could give. They were unable to use the fire support, however, because no one knew the disposition of the friendly column.

Within minutes the fighting had become face to face and hand to hand. After the battle, bodies of U.S. and NVA soldiers were found locked in battle or side by side.

Brown ordered Co. B, 1/5th Cav., to march overland from Columbus to march toward the tail of the column. At the same time, Co. B, 2/7th Cav. was to be helicoptered into Albany from Camp Holloway.

When the soldiers in the column could mark their positions with smoke, the Air Force planes hit everything outside the smoke with napalm. This helped keep some of the attackers at bay, but there were also U.S. troops outside those positions getting hit by the jellied gas. Still the planes came in with their deadly cargo whenever a group of NVA could be identified.

About 4:30 p.m., the reinforcing company hooked up with Forrest’s company, and about two hours later, the first helicopters carrying Company B, 2/7th, roared into LZ Albany. The ships of the 229th were again doing double duty bring in troops and ammunition and taking out casualties.

Throughout the afternoon and into the night, U.S. soldiers along the column tried to fight their way out of the kill zone. Some, wounded or separated from their comrades, would eventually find their way to nearby firebases.

The next morning, with most of the NVA force faded away, the two 5th Cav. companies made their way through the carnage that was once the battalion column to the LZ.

It was now time for the U.S. force to begin collecting its wounded, dead and missing. Many of the dead were soldiers who had been executed after being found wounded.

The two companies helped patrol outside the LZ until about 2 p.m. then left for an uneventful march back to LZ Columbus. They arrived about 5 p.m.

Recovery of the dead took most of two days to accomplish, and it was months before the last five missing soldiers were accounted for.

At LZ Albany, the U.S. force suffered 155 killed and 124 wounded, to 403 NVA killed and about 150 wounded.

(Ref: We Were Soldiers Once…And Young, by retired Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore and Joseph Galloway)

HERRICK, HENRY T

- 2/LT USA

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF BIRTH: 08/31/1941

- DATE OF DEATH: 11/15/1965

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 12/03/1965

- BURIED AT: SECTION 37 SITE 3035

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard