From a contemporary news report:

“General Hoyt Vandenberg died of cancer at Walter Reed Medical Center, April 2, 1954. He had retired from the Air Force on June 30, 1953. For many of his years he had to contend against his youthful appearance that seemingly conflicted with the high ranks that he held. Handsome in appearance, he stood 6 feet tall and kept himself at a trim 165 pounds. His son, Hoyt Vandenberg, Jr., followed him at West Point.

When he became the nation’s leading military airman he was just 49 years old. He had been born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, January 24, 1899. His father, William Collins Vandenberg, was president of a book binding company. His uncle, Arthur H. Vandenberg, went from newspaper publishing in Grand Rapids to high rank as a leading Republican Senator.

His last controversy in the service came just before his retirement, when he opposed Defense Secretary Wilson on a $5 billion budget reduction for the Air Force. He maintained that the cut backed by Wilson would reduce U.S. military aviation to a “one-shot Air Force” inferior to that of the Soviet Union. He said it was another instance of “start-stop” planning of a kind that had impeded Air Force development in previous years. The cut in appropriations went into effect in July 1953, immediately after his retirement.

The huge Air Force Base in California is named in his honor.

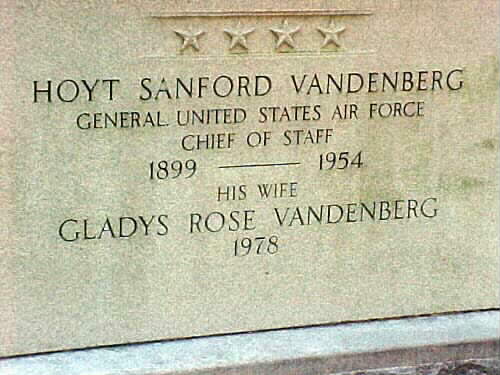

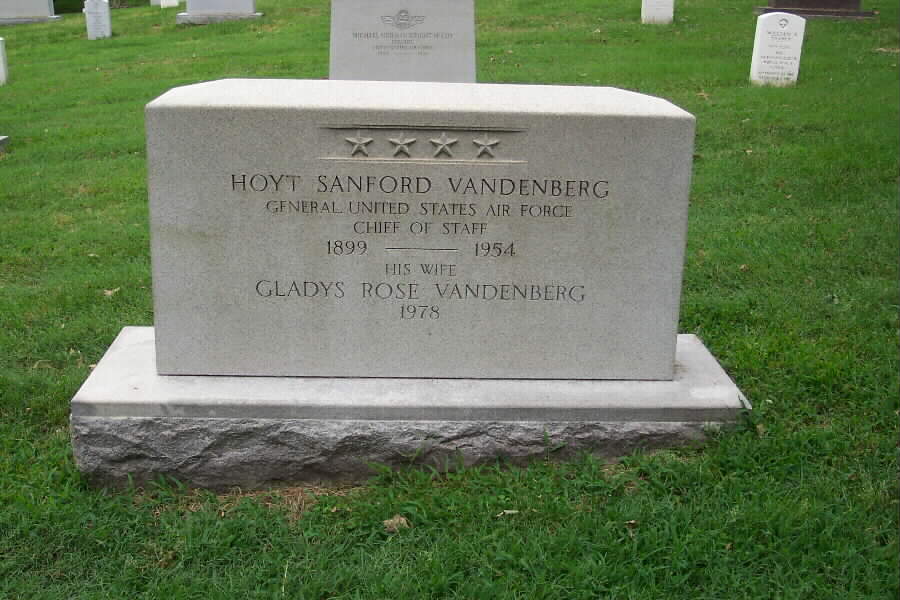

He is buried in Section 30 of Arlington National Cemetery.

His wife, Gladys Rose Vandenberg (died January 9, 1978), started the concept of the “Arlington Ladies” while he was Air Force Chief of Staff. The program provides that a military lady of the appropriate service represents the service chief at all military funerals at Arlington. She is buried with her husband in Section 30.

Courtesy of the United States Air Force

General Hoyt S. Vandenberg was the second chief of staff of the U.S. Air Force, Washington, D.C.

The general was born at Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1899. He graduated from the U.S. Military Academy June 12, 1923, and commissioned a second lieutenant in the Air Service.

General Vandenberg graduated from the Air Service Flying School at Brooks Field, Texas, in February 1924, and from the Air Service Advanced Flying School at Kelly Field, Texas, in September 1924.

His first assignment was with the Third Attack Group at Kelly Field, where he assumed command of the 90th Attack Squadron. In 1927, he became an instructor at the Air Corps Primary Flying School at March Field, Calif. He went to Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, in May 1929, to join the Sixth Pursuit Squadron, and assumed command of it the following November.

Returning in September 1931, he was appointed a flying instructor at Randolph Field, Texas, and became a flight commander and deputy stage commander there in March 1933. He entered the Air Corps Tactical School at Maxwell Field, Alabama, in August 1934, and graduated the following June. Two months later he enrolled in the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and completed the course in June 1936. He then became an instructor at the Air Corps Tactical School at Maxwell Field, where he taught until September 1936, when he entered the Army War College.

After graduating from the War College in June 1939, General Vandenberg was assigned to the Plans Division in the Office of the Chief of Air Corps. A few months after the United States entered World War II, he became operations and training officer of the Air Staff. For his services in these two positions he received the Distinguished Service Medal.

In June 1943, General Vandenberg was assigned to the United Kingdom and assisted in the organization of the Air Forces in North Africa. While in Great Britain he was appointed chief of staff of the 12th Air Force, which he helped organize. On February 18, 1943, General Vandenberg became chief of staff of the Northwest African Strategic Air Force and with this air force he flew on numerous missions over Tunisia, Italy, Sardinia, Sicily and Pantelleria during the North African campaign. He was awarded both the Silver Star and the Distinguished Flying Cross for his services during this time. For his organizational ability with the 12th Air Force and his work as chief of staff of the Northwest African Strategic Air Force, he was awarded the Legion of Merit.

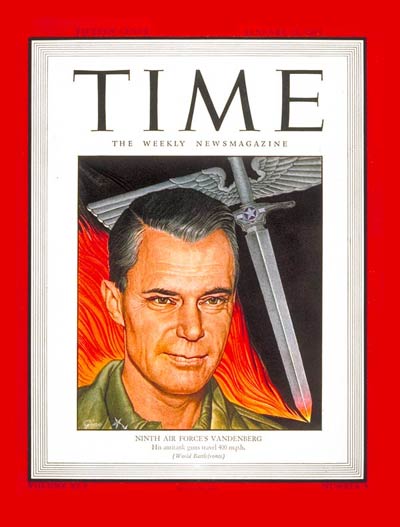

General Vandenberg, in August 1943, was assigned to Air Corps headquarters as deputy chief of air staff. A month later he became head of an air mission to Russia, under Ambassador Harriman, and returned to the United States in January 1944. Two months later he was transferred to the European theater, and in April 1944, was designated deputy air commander in chief of the Allied Expeditionary Forces and commander of its American Air Component. In August 1944, General

Vandenberg assumed command of the Ninth Air Force. On November 28, 1944, he received an oak leaf cluster to the Distinguished Service Medal for his part in planning the Normandy invasion.

He was appointed assistant chief of air staff at Air Corps headquarters in July 1945. The following January he became director of Intelligence on the War Department general staff where he serviced until his appointment in June 1945, as director of Central Intelligence. He returned to duty with the Air Corps in April 1947, and on June 15, 1947, became deputy commander and chief of air staff. He was designated vice chief of staff of the Air Force on Oct. 1, 1947, and promoted to the rank of general. On April 30, 1948, General Vandenberg became chief of staff of the Air Force, succeeding General Carl Spaatz. He was renominated by President Harry S. Truman for a second term as chief of staff March 6, 1952, to June 30, 1953, and the nomination was confirmed by the Senate on April 28, 1952.

General Vandenberg retired from active duty June 30, 1953. He has been awarded the Distinguished Service Medal with oak leaf cluster, Silver Star, Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters, Bronze Star, Victory Medal, American Campaign Ribbon, American Defense Ribbon and the European-African-Middle East Campaign Ribbon.

His foreign decorations include: Mexican Military Order of Merit; Netherlands Order of Orange Nassau (Grand Officer with Swords); Brazilian Cruz del Sol (Grand Officer), and Medal of War; Luxembourg Order of Adolph von Nassau (Grand Cross), and Croix de Guerre; Belgian Order of Leopold I (Grand Officer with Palms); and Croix de Guerre with Palms; British Order of the Bath (Knight Commanders Cross); Polish Order of Polish Restoration (2nd Class); Portuguese Ordem de Avis, Gra Cruiz; Egyptian L’Ordre Du Nil Grand Cordon; Chinese Order of Pao Ting (Tripod with Grand Cordon); Chilean Medallia Militar de Primerera Clase; Argentine General Staff Emblem and the Military Order of Italy.

Former Air Force Chief of Staff

General Hoyt S. Vandenberg

Special Military Funeral

2-5 April 1954

General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, Chief of Staff of the Air Force from 1948 to 1953, died at Walter Reed General Hospital on 2 April 1954 at the age of fiftyfive. He had been ill of cancer for several years and hospitalized since 7 October 1953.

When it became known that death was imminent, Headquarters, Department of the Air Force, began to draw up plans for a Special Military Funeral for the general. Under current Department of Defense policies, General Vandenberg’s status as a retired former Chief of Staff entitled him to a “combined services full honor ceremony.” Authority for according the greater ceremony of a Special Military Funeral rested with the Secretary of Defense; in this case it would come from Secretary Charles E. Wilson.

Several months before the general’s death, the Air Force Chief of Chaplains, Major General Charles I. Carpenter, discussed funeral arrangements for the general with his wife, Gladys Rose Vandenberg. At that time, she preferred a family service in St. Joseph’s Chapel at the Washington National Cathedral and at Arlington National Cemetery.

Wishing to hold a more elaborate ceremony for the distinguished Air Force official, Air Force Chief of Staff General Nathan D. Twining, in January 1954, directed Brigadier General Monro MacCloskey, who had been a member of the same U.S. Military Academy company as General Vandenberg and who was a long-time friend of the Vandenberg family, to take up the matter again with Mrs. Vandenberg. General MacCloskey and Mrs. Vandenberg reached agreement on a larger ceremony. General Vandenberg’s body was to lie in St. Joseph’s Chapel at the Washington National Cathedral until the funeral service, which was to be held in the cathedral nave and was to be conducted according to rites of the Episcopal Church, of which the Vandenbergs were communicants. The body was then to be moved in procession to the entrance of Arlington National Cemetery. From there a military escort was to accompany the cortege to the gravesite in Section 30, near the graves of William Howard Taft and James V. Forrestal.

On 2 April General Twining formally assigned primary responsibility for arranging the funeral to Headquarters Command, US Air Force, at Bolling Air Force Base, Washington, D.C. Brigadier General Stoyte O. Ross, who headed the command, immediately established a liaison office in the Pentagon which was manned around the clock through 5 April, the day of the funeral. General Ross’s headquarters meanwhile issued a 44-page “Special Military Funeral Plan” with ten annexes, a document based on the plan worked out by General MacCloskey and Mrs. Vandenberg.

The Air Adjutant General, Colonel Kenneth E. Thiebaud, was in charge of sending out announcements of the funeral (in effect, invitations to attend) to family, friends, and dignitaries. Colonel Thiebaud also handled seating plans for the cathedral and other matters of protocol, including details covering the attendance of the family, honorary pallbearers, and special honor guard. Lieutenant General Emmett O’Donnell, Jr., the Air Force Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, was responsible for conducting necessary “negotiations with the Secretary of Defense, appropriate overseas commanders, and next of kin.”

At 0815 on 3 April General Vandenberg’s body, which had been taken from the hospital to the Rinaldi Funeral Home, was moved in procession to the Washington National Cathedral. Eight body bearers, two each from the Air Force, Army, and Navy and one each from the Marine Corps and Coast Guard, led by an Air Force officer, handled the casket. Heading the procession to the cathedral was a police escort, and following, with intervals of twenty-five yards between, were the escort commander, the clergy, the hearse, the body bearers, and a second police escort.

Awaiting the procession at the Bethlehem Chapel entrance to the cathedral were a cordon of sixteen airmen and an officer, the general’s personal flag bearer, and an Air Force ceremonial band. The band sounded four ruffles and flourishes and played the “General’s March” and the honor cordon presented arms as the body bearers took the casket from the hearse. Following the clergy, the body bearers carried the casket through the Bethlehem Chapel entrance to St. Joseph’s Chapel. In column behind the casket were two representatives of the mortuary, the flag bearer, and (according to the recollection of the cathedral verger) the family and honorary pallbearers. The casket was placed on a bier and an honor guard took post immediately.

The honor guard consisted of one officer and five noncommissioned officers; sixteen men from the enlisted ranks, four from each of the four armed forces; and one officer, two petty officers, and two other enlisted men from the Coast Guard. These troops were provided by the 1100th Air Base Group, the 3d Infantry, and the Potomac River Naval Command (which arranged all Navy, Marine, and Coast Guard participation in the ceremonies). Mess, housing, transportation, and other administrative support for the honor guard at the chapel were responsibilities of the commander of the 1100th Air Base Group, stationed at Boiling Air Force Base.

The honor guard stood watch from the morning of 3 April until noon on 5 April, performing its vigil in half-hour reliefs. Each daytime relief comprised one officer and four noncommissioned officers. A night relief consisted of one noncommissioned officer and four enlisted men. The reliefs were posted by service, not in combined formations. (It appears that the Coast Guard sentinels served in the naval watch rotation.) As is customary in the Protestant Episcopal Church, the casket remained closed during this period and during the funeral service as well.

The commander of the 1401st Air Base Wing, a Military Transport Service unit stationed at Bolling Air Force Base, provided a floral detail whose members received each flower offering at the cathedral and recorded the name of the sender. The detail worked around the clock in three shifts, an officer, three noncommissioned officers, and seven enlisted men in each shift. Although the actual arranging of flowers was done by personal friends of the Vandenberg family, in particular, by Mrs. William Pope Anderson of Washington, DC, the detail from the Military Transport Service assisted the family friends later in the nave of the cathedral and at the gravesite.

The Air Adjutant General’s office had meanwhile issued announcements of the funeral service to Washington officials as required by protocol and to individuals selected by Mrs. Vandenberg in consultation with General MacCloskey. These included retired Air Force general officers; West Point classmates of General Vandenberg; representatives of the Air Force Officers’ Wives Club, Air Force Association, Air Force Arlington Committee, Civil Air Patrol, Air Force Aid Society, Air Force Historical Foundation, and other associations; and members of the aircraft and airline industries. Former President Harry S. Truman was invited but was not able to attend.

Among those invited to the funeral were twenty-four men who were asked to serve as honorary pallbearers. Some of these were the general’s personal friends, others were associates from the military services, the Central Intelligence Agency, the diplomatic corps, and the aircraft industry. Seventeen were able to participate and officer guides were detailed to assist them during the ceremonies.

The funeral service announcements, along with tickets for seats in the cathedral, were delivered by courier to residents of the Washington area. Others were notified by telegraph and given seating information. Fifty ushers, all officers from Bolling Air Force Base and Andrews Air Force Base, were appointed and given detailed instructions on directing the seating in the various sections of the cathedral nave.

A minor ceremonial arrangement peculiar to the services for General Vandenberg concerned the special honor guard. This formation traditionally consists of the chairman of the joint Chiefs of Staff, the chiefs and vice chiefs of staffs of the three military departments, and the commandants and assistant commandants of the Marine Corps and Coast Guard. Out of a decision to make this group an even number, General J. Lawton Collins, formerly Army Chief of Staff and now US Military Representative to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, was added. Later, when it turned out that the assistant commandant of the Coast Guard could not attend, the chief of the office of operations of that service was substituted.

At noon on 5 April the body bearers moved General Vandenberg’s casket from St. Joseph’s Chapel to a bier in the nave. The floral pieces were brought into the nave and arranged around the pulpit and lecturn, and the honor guard again was posted. This time, in contrast to the posting of reliefs by service during the vigil in St. Joseph’s Chapel, a joint service relief took post in the nave, a system followed until the beginning of the funeral service at 1400.

Dignitaries attending the funeral included President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Secretary of Defense, the three service secretaries, the Secretary of State, and the Secretary of the Treasury. The service was conducted by the Very Reverend Francis B. Sayre, dean of the Washington National Cathedral, who was assisted by the Reverend Frank E. Pulley, Chaplain of the US Military Academy. In the course of a simple ceremony read from the Book of Common Prayer, the West Point Cadet Choir sang the academy hymn, “The Corps.” No eulogy was delivered.

At the conclusion of the service, President Eisenhower left the cathedral and returned to the White House. After his departure the cathedral verger and the clergy led the way from the nave of the cathedral, followed by the honorary pall bearers who formed a cordon along the north transept aisle. Two body bearers then wheeled the casket on its movable bier through the cordon of pallbearers to the north entrance, where the remaining body bearers waited. Here the full contingent of body bearers took the casket and, followed by the personal flag bearer, family group, special honor guard, and other mourners, carried it through a cordon of sixteen airmen stationed on the entrance steps. The Air Force ceremonial band, across the street from the cortege vehicles, played while the casket was carried out and placed in the hearse. Those who were to travel in the cortege entered their automobiles and the motorcade departed. The body bearers and flag bearer proceeded by a separate route in order to reach Memorial Gate of the cemetery ahead of the procession.

The cortege moved to Arlington National Cemetery via Woodley Road, Cathedral Avenue, Rock Creek Parkway, Memorial Bridge, and Memorial Drive. Waiting in column on Memorial Drive was the military escort, whose units included the US Air Force Band, the US Army Band, a battalion of cadets from the US Military Academy, a battalion of midshipmen from the US Naval Academy, a battalion of air cadets from Lackland Air Force Base, and a combined services battalion. This last battalion, commanded by a lieutenant colonel from the 3d Infantry with a staff of three company grade officers from the Marine Corps, Navy, and Air Force, contained a reduced company (one officer and forty-one men) each from the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and Air Force. It was massed on an eight-man front, whereas the other battalions were massed on a nine-man front. Only the cadets and midshipmen carried arms. Also waiting were the body bearers, personal flag bearer, and a combined services national color detail.

When the cortege arrived it proceeded to the rear escort unit, where it halted while the color detail took position at the head of the procession, with the body bearers on either side of the hearse and the personal flag bearer immediately be hind the hearse. The escort commander (an Air Force major general) and his staff of field grade Army, Marine Corps, and Navy officers then moved to the head of the military escort and led the full procession into the cemetery.

The column proceeded on Roosevelt Drive, Weeks Drive, and Sheridan Drive toward the gravesite in Section 30. Along the route was a cordon of airmen from Bolling and Andrews Air Force Bases posted at intervals of about fifteen feet. When the hearse entered Memorial Gate, the 3d Infantry battery, in position along Weitzel Drive at the north end of the cemetery, began a 17-gun salute, firing the rounds at fifteen-second intervals. Before the procession reached the gravesite, six B-47 Stratojets flew over in V-formation with the second position on the right empty as a salute to a fallen comrade. The bombers were followed by a flight of sixteen F-84 Thunderjets and sixteen F-86 Sabrejets.

When the procession reached the intersection of Sheridan Drive with Sherman Drive just above the gravesite, the escort commander and all escort units except the US Air Force Band and US Military Academy Cadet Company A-1 (General Vandenberg’s company when he was a cadet) turned west on Sherman away from the gravesite. These units, not scheduled for further participation in the ceremonies, continued west on Sherman to the cemetery’s administrative area parking lot and boarded buses to return to their respective duty stations.

Already in position at the graveside were an Army company, Marine Corps company, Navy company, and an Air Force squadron, each consisting of three officers and sixty-six men. These units were headed by an Air Force colonel (with a

combined services staff of field grade officers) who would serve as escort commander during the graveside rites. Upon reaching the graveside the Air Force Band, Cadet Company A-1, and the national color detail joined the formation, in which each company was massed on a six-man front at close interval.

After the cortege halted on Sheridan Drive opposite the gravesite, the honorary pallbearers dismounted and formed a cordon along a pathway leading to the grave. The special honor guard and the Vandenberg family moved directly to positions at the grave. (Diagram 14) The body bearers then removed the casket from the hearse and, preceded by the clergy and followed by the personal flag bearer, carried General Vandenberg’s casket to the grave. When the casket cleared the honorary pallbearers, they followed in a column of two to their graveside positions. As the casket was moved, the escort troops saluted and the band played four ruffles and flourishes and the “General’s March.”

Dean Sayre and Chaplain Pulley performed the graveside service. At its conclusion, the escort units saluted and the 3d Infantry battery fired seventeen guns. A bugler then sounded taps, which was echoed by a second bugler. At the last note the escort troops ordered arms. The body bearers then folded the flag that had draped the casket and handed it to Dean Sayre. He in turn presented it to the general’s son, Lieutenant Hoyt S. Vandenberg, Jr., who received it for his mother.

The ceremonies for General Vandenberg had been marked by several departures from the prescribed Special Military Funeral, notably by the absence of the horse-drawn caisson, the omission of three volleys by a firing squad at the grave side, and the addition of a flyover of jet aircraft with one plane missing from the formation.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard