Humbert Roque Versace was born on July 2, 1937 and joined the Armed Forces while in Norfolk, Virginia.

He served in the United States Army and in six years of service, he attained the rank of Captain. He began a tour of duty on in the Republic of Vietnam on 12 May 1962.

Humbert Roque Versace is listed as Missing in Action. There is a memorial stone in Arlington National Cemetery to the Captain’s memory. His father, Humbert Joseph Versace, United States Military Academy Class of 1933, is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Note: Captain Versace’s mother, Marie Teresa Rios Versace (Pen Name: Tere Rios) died on October 17, 1999 and was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery.

One Last Tribute to Captain Versace

A visit last week to Arlington National Cemetery by family and friends brought an emotional end to a remarkable series of events this month honoring Rocky Versace.

Versace, an Army captain, was executed in September 1965 by his Viet Cong captors. His heroism while in captivity was belatedly recognized at these events after a lengthy campaign waged by a group calling itself the Friends of Rocky Versace, his West Point classmates and other supporters inside and outside the military.

“It was truly extraordinary,” Rocky Versace’s brother, Stephen, an administrator with the University of Maryland, said Monday. “It really brought closure to a lot of them.”

Versace, who would have turned 65 this month, grew up in Alexandria and attended Gonzaga College High School in Washington.

On July 6, hundreds gathered for the dedication of the Captain Rocky Versace Plaza and Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Alexandria. The plaza, located at the Mount Vernon Recreation Center near where Versace grew up, includes the names of 65 Alexandrians who were killed in Vietnam inscribed in a circular seating area surrounding the memorial.

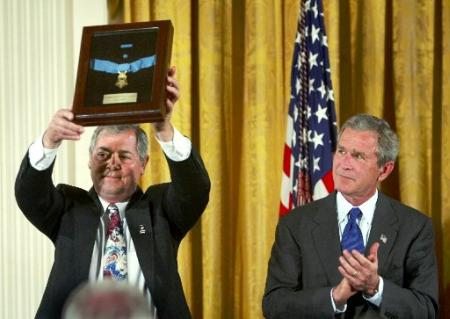

On July 8, in a ceremony in the White House East Room, Versace was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Bush for his heroism, the first time an Army POW has received the nation’s highest honor for actions in captivity.

“In his defiance and later his death, he set an example of extraordinary dedication that changed the lives of his fellow soldiers who saw it firsthand,” Bush said. “His story echoes across the years, reminding us of liberty’s high

price, and of the noble passion that caused one good man to pay that price in full.”

Finally, in a simple ceremony at the Pentagon on July 9, Secretary of the Army Thomas E. White and Army Chief of Staff Gen. Eric K. Shinseki inducted Versace into the Pentagon Hall of Heroes.

“First and foremost, we are here today to recognize Rocky’s example as the model of adherence to the Code of Conduct; as the model of physical and moral courage; as the model of complete selflessness; as the model of one

who never broke faith with God and country — regardless of the cost,” White said. “But our presence here today is also a tribute to the many in his family, and in our Army family, who never broke faith with Rocky.”

After the Pentagon ceremony, members of the Friends of Rocky Versace and family members drove to Versace’s memorial marker in Arlington — his remains were never recovered. When family members left, the friends stayed

behind for a few minutes.

Duane Frederic, a Cleveland postal worker who did important research supporting the Medal of Honor submission, read a poem about Rocky’s heroism written by fellow prisoner Nick Rowe. “Each member spoke his piece to Rocky as we sought closure,” said John Gurr, a West Point classmate and group member now living in the Charlottesville area.

Joe Flynn, a friend of Rocky Versace’s during his Alexandria years, suggested they end by singing “God Bless America.” It was the song that Versace was singing the last time his fellow captors heard him.

After everyone had returned to their homes last week, Gurr sent an e-mail to his West Point classmates with this coda:

“We came, Rocky. We were late, but we came. We came in force. We came with Rocky’s family, Special Forces representatives, Congressmen, and perhaps it should be said that we came following the utterly indomitable Friends of Rocky Versace — they led the way.”

resident Awards Posthumous Medal of Honor to Vietnam War Hero

Remarks by the President at Presentation of Medal of Honor

The East Room

July 8, 2002

3:07 P.M. EDT

THE PRESIDENT: Good afternoon, and welcome to the White House. It’s a — this is a special occasion. I am honored to be a part of the gathering as we pay tribute to a true American patriot, and a hero, Captain Humbert “Rocky” Versace.

Nearly four decades ago, his courage and defiance while being held captive in Vietnam cost him his life. Today it is my great privilege to recognize his extraordinary sacrifices by awarding him the Medal of Honor.

I appreciate Secretary Anthony Principi, the Secretary from the Department of Veteran Affairs, for being here. Thank you for coming, Tony. I appreciate Senator George Allen and Congressman Jim Moran. I want to thank Paul Wolfowitz, the Deputy Secretary of Defense; and General Pete Pace, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs; Army General Eric Shinseki — thank you for coming, sir. I appreciate David Hicks being here. He’s the Deputy Chief of Chaplains for the United States Army.

I want to thank the entire Versace family for coming — three brothers and a lot of relatives. Brothers, Dick and Mike and Steve, who’s up here on the stage with me today. I appreciate the classmates and friends and supporters of Rocky for coming. I also want to thank the previous Medal of Honor recipients who are here with us today. That would be Harvey Barnum and Brian Thacker and Roger Donlon. Thank you all for coming.

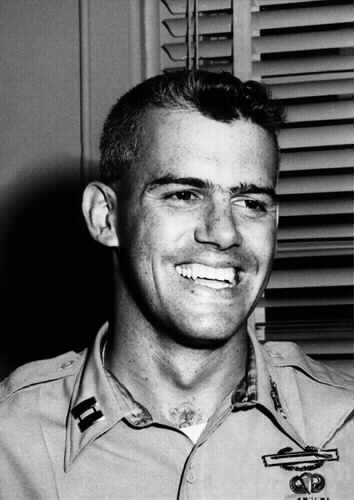

Rocky grew up in this area and attended Gonzaga College High School, right here in Washington, D.C. One of his fellow soldiers recalled that Rocky was the kind of person you only had to know a few weeks before you felt like you’d known him for years. Serving as an intelligence advisor in the Mekong Delta, he quickly befriended many of the local citizens. He had that kind of personality. During his time there he was accepted into the seminary, with an eye toward eventually returning to Vietnam to be able to work with orphans.

Rocky was also a soldier’s soldier — a West Point graduate, a Green Beret, who lived and breathed the code of duty and honor and country. One of Rocky’s superiors said that the term “gung-ho” fit him perfectly. Others remember his strong sense of moral purpose and unbending belief in his principles.

As his brother Steve once recalled, “If he thought he was right, he was a pain in the neck.” (Laughter.) “If he knew he was right, he was absolutely atrocious.” (Laughter.)

When Rocky completed his one-year tour of duty, he volunteered for another tour. And two weeks before his time was up, on October the 29th, 1963, he set out with several companies of South Vietnamese troops, planning to take out a Viet Cong command post. It was a daring mission, and an unusually dangerous one for someone so close to going home to volunteer for.

After some initial successes, a vastly larger Viet Kong force ambushed and overran Rocky’s unit. Under siege and suffering from multiple bullet wounds, Rocky kept providing covering fire so that friendly forces could withdraw from the killing zone.

Eventually, he and two other Americans, Lieutenant Nick Rowe and Sergeant Dan Pitzer, were captured, bound and forced to walk barefoot to a prison camp deep within the jungle. For much of the next two years, their home would be bamboo cages, six feet long, two feet wide, and three feet high. They were given little to eat, and little protection against the elements. On nights when their netting was taken away, so many mosquitos would swarm their shackled feet it looked like they were wearing black socks.

The point was not merely to physically torture the prisoners, but also to persuade them to confess to phony crimes and use their confessions for propaganda. But Rocky’s captors clearly had no idea who they were dealing with. Four times he tried to escape, the first time crawling on his stomach because his leg injuries prevented him from walking. He insisted on giving no more information than required by the Geneva Convention; and cited the treaty, chapter and verse, over and over again.

He was fluent in English, French and Vietnamese, and would tell his guards to go to hell in all three. Eventually the Viet Cong stopped using French and Vietnamese in their indoctrination sessions, because they didn’t want the sentries or the villagers to listen to Rocky’s effective rebuttals to their propaganda. Rocky knew precisely what he was doing. By focusing his captors’ anger on him, he made life a measure more tolerable for his fellow prisoners, who ooked to him as a role model of principled resistance.

Eventually the Viet Cong separated Rocky from the other prisoners. Yet even in separation, he continued to inspire them. The last time they heard his voice, he was singing “God Bless America” at the top of his lungs.

On September the 26th, 1965, Rocky’s struggle ended in his execution. In his too short life, he traveled to a distant land to bring the hope of freedom to the people he never met. In his defiance and later his death, he set an example of extraordinary dedication that changed the lives of his fellow soldiers who saw it firsthand. His story echoes across the years, reminding us of liberty’s high price, and of the noble passion that caused one good man to pay that price in full.

Last Tuesday would have been Rocky’s 65th birthday. So today, we award Rocky — Rocky Versace — the first Medal of Honor given to an Army POW for actions taken during captivity in Southeast Asia. We thank his family for so great a sacrifice. And we commit our country to always remember what Rocky gave — to his fellow prisoners, to the people of Vietnam, and to the cause of freedom.

July 8, 2002 — Forty years ago, Army Captain Humbert Roque ‘Rocky’ Versace wanted to become a priest and work with Vietnamese orphans. He’d been accepted into a seminary, but his dream was not to be fulfilled.

Two weeks before he was due to return home, Versace, 27, was captured on October 29, 1963, by Viet Cong guerrillas who spent the next two years torturing and trying to brainwash him. In return, he mounted four escape attempts, ridiculed his interrogators, swore at them in three languages and confounded them as best he could, according to two U.S.soldiers captured with him.

The witnesses said the unbroken Versace sang “God Bless America” at the top of his lungs the night before he was executed on September 26, 1965. His remains have never been recovered.

Nominations starting in 1969 to award Versace the Medal of Honor failed; he received the Silver Star posthumously instead. Language added by Congress in the 2002 Defense Authorization Act ended the standoff and authorized the award of the nation’s highest military decoration for combat valor.

Today, President Bush and the nation recognized Versace for his courage and defiance. Bush said the Army captain was “a soldier’s soldier, a West Point graduate, a Green Beret who lived and breathed the code of duty, and honor and country.

“Last Tuesday would have been Rocky’s 65th birthday,” the president said. “So today, we award Rocky the first Medal of Honor given to an Army POW for actions taken during captivity in Southeast Asia.

“In his defiance and later his death,” Bush said, “he set an example of extraordinary dedication that changed the lives of his fellow soldiers who saw it firsthand. His story echoes across the years, reminding us of liberty’s high price and of the noble passion that caused one good man to pay that price in full.”

Versace’s brother Steve accepted the award during a White House ceremony witnessed by family members and many of the friends and supporters who had worked for years to have Versace’s Silver Star upgraded.

Versace grew up in Norfolk and Alexandria, Virginia, and attended Gonzaga College High School. He graduated from West Point in 1959 and became a member of the Ranger Hall of Fame at Fort Benning, Georgia, and a member of Army Special Forces.

Bush said a fellow soldier recalled that Versace “was the kind of person you only had to know a few weeks before you felt like you’d known him for years.” As an intelligence adviser in the Mekong Delta, he befriended many local citizens. “He had that kind of personality,” the president said.

“One of Rocky’s superiors said that the term ‘gung-ho’ fit him perfectly,” he noted. “Others remember his strong sense of moral purpose and unbending belief in his principles. As his brother Steve once recalled, if he thought he was right, he was a pain in the neck. If he knew he was right, he was absolutely atrocious.”

The Vietnamese tortured prisoners to persuade them to confess to phony crimes. Versace gave only his name, rank and serial number as required by the Geneva Convention. “He cited the treaty chapter and verse over and over again,” the president said. “He was fluent in English, French and Vietnamese and would tell his guards to go to hell in all three.”

Versace knew what he was doing, Bush said. “By focusing his captors’ anger on him, he made life a measure more tolerable for his fellow prisoners, who looked to him as a role model of principled resistance.”

35 Years After His Death, Army Vietnam POW Earns a Medal of Honor for Bravery in Captivity

By Steve Vogel

Thursday, May 23, 2002

More than 35 years after he was executed by his Viet Cong captors in Vietnam, Rocky Versace is close to receiving his nation’s highest honor.Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld recently forwarded to the White House a package that would award Versace, a former Alexandria resident, the Medal of Honor, according to family members and military officials. Legislation authorizing the medal for Versace already has been passed by Congress and signed by President Bush. A date for presenting the medal will be set by the White House.

“The family is just elated about this,” said Rocky’s brother, Steve Versace, an administrator with the University of Maryland in College Park.

Unlike the Air Force, Navy and Marines, the Army has never awarded the Medal of Honor to a POW from Vietnam for actions during captivity. Pentagon officials said it would be the first time in the modern era that the medal has gone to an Army POW for heroism during captivity in any war.

Green Beret Capt. Humbert Roque Versace was taken prisoner in October 1963, during an operation near U Minh Forest, a Viet Cong stronghold. Over the next two years, Versace defied his captors’ attempts to indoctrinate him, so infuriating them that they executed him in 1965. He was 27.

“He told them to go to hell in Vietnamese, French and English,” one of Versace’s fellow captives, Dan Pitzer, who died in 1997, told an oral historian. “He got a lot of pressure and torture, but he held his path. As a West Point grad, it was duty, honor, country. There was no other way. He was brutally murdered because of it.”

Another prisoner who was held with Versace, Maj. Nick Rowe, escaped after five years and later made an impassioned plea to President Richard M. Nixon that Versace receive the Medal of Honor, describing how his resistance deflected punishment from other captives and steeled their will to resist. The Army instead awarded a Silver Star to Versace.

Brother Steve Versace credits the Special Operations Command, Rocky’s classmates from the West Point Class of 1959 and a group of Alexandrians called Friends of Rocky Versace for influencing the Medal of Honor decision.

The award ceremony will be “the culmination of three years of intense work on their part,” Steve Versace said. “These people have put their lives on hold to help with this.”

The Medal of Honor is one of two salutes for Rocky Versace in the coming months.

On July 6, a plaza in the Del Ray neighborhood of Alexandria where Versace grew up is scheduled to be dedicated, honoring him and more than 60 other Alexandrians who died in the Vietnam War. The plaza will include a bronze statue of Versace being sculpted by Toby Mendez.

CHIEF OF STAFF OF THE ARMY REMARKS

MEDAL OF HONOR INDUCTION CEREMONY

CAPTAIN HUMBERT “ROCKY” VERSACE: 9 JULY 2002

(AS PREPARED)

SECRETARY WOLFOWITZ, OTHER MEMBERS OF THE DEFENSE SECRETARIAT – – THANK YOU FOR JOINING US TODAY; SECRETARY OF THE ARMY, TOM WHITE – – OTHER MEMBERS OF THE ARMY SECRETARIAT; MEMBERS OF THE VERSACE FAMILY – – WE ARE PROUD FOR YOU AND PROUD TO HAVE YOU AS OUR SPECIAL GUESTS TODAY; GENERAL ED BURBA, GENERAL FRED FRANKS – – AND OTHER MEMBERS OF THE DISTINGUISHED WEST POINT CLASS OF 1959; FELLOW GENERAL AND FLAG OFFICERS; OTHER DISTINGUISHED GUESTS – – LADIES AND GENTLEMEN:

CEREMONIES IN THIS HALL OF HEROES ARE ALWAYS EXTRAORDINARILY MOVING, ALWAYS ABOUT SINGULARLY OUTSTANDING DISPLAYS OF CHARACTER AND ACTS OF HEROISM. TODAY IS NO DIFFERENT. WHEN WE GATHER HERE TO HONOR SOLDIERS, WE DO SO TO RECOGNIZE THOSE ACTS OF VALOR WHICH GO SO FAR BEYOND HUMAN COMPREHENSION THAT NONE OF US CAN EXPLAIN THEM VERY WELL, ACTS OF SACRIFICE SO PROFOUND THAT ALL OF US FEEL SOMEWHAT UNEASY IN THE COMMONNESS OF OUR HUMANITY. SOLDIERS WHO RECEIVE THE MEDAL OF HONOR HAVE DEMONSTRATED A LEVEL OF COURAGE AND A QUALITY OF CHARACTER THAT EVEN THOSE WHO HAVE STOOD WITH THEM IN BATTLE ARE UNABLE TO DESCRIBE THE DEPTH OF DETERMINATION AND THE HEIGHTS OF BRAVERY ATTAINED BY THOSE FEW WHO RECEIVE OUR NATION’S HIGHEST AWARD FOR VALOR. IT IS NOT POSSIBLE TO TRAIN FOR THE CIRCUMSTANCES THAT MAKE THESE ACTS SUPREMELY NOTEWORTHY. NO ONE IS EVER EXPECTED TO MAKE THE KIND OF SACRIFICE THAT IS REQUIRED TO RECEIVE THE MEDAL OF HONOR. AND ON THOSE RARE OCCASIONS WHEN IT IS AWARDED, IT MOST OFTEN RECOGNIZES REMARKABLE PHYSICAL COURAGE OVER THE COURSE OF A DAY OR TWO OF BATTLE OR DURING A FEW HOURS OF INTENSE COMBAT. IN SOME CASES, IT ACKNOWLEDGES EXTREME HEROISM SPANNING A FEW MOMENTS OF SELFLESS SACRIFICE DURING BATTLE.

THE MAN WE HONOR TODAY POSSESSED UNQUESTIONED PHYSICAL COURAGE – – BUT HE ALSO DEMONSTRATED DEEP MORAL COURAGE AND STAMINA THAT SPANNED NEARLY TWO YEARS.

AMONG THE DISTINGUISHED RECIPIENTS OF THE MEDAL OF HONOR, CAPTAIN HUMBERT ROQUE VERSACE IS THE ARMY’S UNIQUELY HEROIC ADDITION TO THEIR ROLL OF HONOR – – HE IS THE FIRST ARMY RECIPIENT TO BE HONORED FOR ACTIONS WHILE A PRISONER OF WAR IN VIETNAM. AND HIS IS A STORY OF A REMARKABLE, UNYIELDING SPIRIT AND AN UNCOMPROMISINGLY FIERCE DEFIANCE – – THE COURAGE NEVER TO SUBMIT OR YIELD. IT IS THE STORY OF A SOLDIER WHO, IN THE WORST OF CIRCUMSTANCES, DEMONSTRATED ALL THAT IS BEST ABOUT OUR PROFESSION AND OUR VALUES. IT IS A STORY ABOUT A MAN SUBJECTED TO THE MOST RELENTLESS ATROCITIES WHO PERSEVERED – – AND IN DOING SO, REVEALED AN UNWAVERING STRENGTH OF CHARACTER THAT INSPIRED ALL WHO WITNESSED HIS TRIUMPH OVER HIS TORMENTORS.

IT IS A STORY OF A MAN WHO, BECAUSE OF INJURIES AND CRIMINAL TREATMENT AT THE HANDS OF HIS ENEMIES, COULD HAVE LOOKED AFTER HIS OWN WELL BEING. INSTEAD, HE NEVER SEEMED TO THINK ABOUT HIS PERSONAL WELFARE.

AND IT IS A STORY OF A MAN WHO ENDURED DAYS, WEEKS, MONTHS, AND ENDLESS YEARS OF INHUMANE ABUSE – – YET MANAGED TO MAINTAIN HIS OWN HUMANITY. HE FACED DESPAIR EACH DAY, YET HE SUSTAINED HOPE AND SHARED IT AS A PRECIOUS GIFT WITH OTHERS. NICK ROWE, A FELLOW CAPTIVE, WOULD DESCRIBE ROCKY VERSACE AS A MAN WHO “DID NOT BREAK, OR EVEN BEND” AMID INJURY, TORTURE, AND DISEASE THAT WE HERE TODAY FIND IT DIFFICULT TO IMAGINE.

AN IMPORTANT, YET INTANGIBLE BOND DEVELOPS AMONG THOSE WHO CHOOSE OUR PROFESSION. IT’S CALLED A SOLDIER’S TRUST, AND MUCH OF WHAT WE DO ON OUR TOUGHEST DAYS RELIES HEAVILY ON IT. CAPTAIN VERSACE’S ACTIONS ARE ALL ABOUT TRUST AND THE LEADERSHIP THAT IT EMPOWERS.

ROCKY VERSACE’S OUTSTANDING SERVICE IN VIETNAM WAS EXTENDED BY HIS DECISION TO GO ON A MISSION WITH A SOUTH VIETNAMESE SELF-DEFENSE UNIT LESS THAN TWO WEEKS BEFORE HIS SCHEDULED DEPARTURE. WHEN THAT MISSION BEGAN TO GO BADLY ON 29 OCTOBER, 1963, CAPTAIN ROCKY VERSACE VOLUNTEERED TO COVER THE WITHDRAWAL OF THE CIDG WHEN THEY WERE SLAMMED BY A LARGE AND VERY HEAVY VIET CONG MAIN FORCE ATTACK. ROCKY VERSACE PROVIDED REAR SECURITY, FIGHTING COURAGEOUSLY UNTIL HIS AMMUNITION WAS EXPENDED, AND HE WAS GRIEVOUSLY WOUNDED.

FOR THE NEXT 23 MONTHS, CAPTAIN VERSACE LIVED UP TO A SOLDIER’S TRUST THROUGH HIS EXEMPLARY ACTIONS:

IMMEDIATELY ASSUMING COMMAND OF HIS FELLOW SOLDIERS; RESISTING EVERY ATTEMPT OF HIS CAPTORS TO BREAK HIS SPIRIT AND GAIN INFORMATION OTHER THAN NAME, RANK, SERVICE NUMBER, AND DATE OF BIRTH; ARGUING WITH HIS CAPTORS IN VIETNAMESE, IN ENGLISH, AND IN FRENCH – – DEMANDING THAT THEY PROVIDE THE PROTECTIONS OF THE GENEVA CONVENTION TO THE PRISONERS HELD WITH HIM; DEFLECTING ATTENTION AND PUNISHMENT AWAY FROM THE SPECIAL FORCES SOLDIERS CAPTURED WITH HIM – – THEN-1LT NICK ROWE AND THEN-SFC DAN PITZER – – ABSORBING THE WORST OF THE PUNISHMENT HIMSELF; REPEATEDLY ATTEMPTING ESCAPE – – THE FIRST TIME, JUST THREE WEEKS AFTER HIS CAPTURE – – CRAWLING BACK INTO THE JUNGLE, UNABLE TO WALK DUE TO PAINFUL, INFECTED LEG WOUNDS RECEIVED DURING THE BATTLE IN WHICH HE WAS CAPTURED. HE WAS A BEACON IN OTHER PRISONERS’ LIVES – – A MODEL OF STRENGTH, A SOURCE OF UNITY, AND A SYMBOL OF HOPE.

NOTHING INSTILLS CONFIDENCE LIKE LEADERS WHO TAKE CHARGE AT THEIR OWN PERIL AND LEAD BY EXAMPLE. ROCKY VERSACE PROVIDED THAT EXAMPLE. IT WOULD HAVE BEEN MUCH EASIER TO BEND – – EVEN A LITTLE. HE WOULD HAVE RECEIVED DESPERATELY NEEDED FOOD, MEDICAL ATTENTION, AND DELIVERY FROM TORTURE AND BEATINGS. A SIMPLE AFFIRMATIVE NOD OR ACKNOWLEDGEMENT WOULD HAVE ENDED HIS TORTURE – – BUT HE REFUSED; THERE WOULD BE NO COMPROMISE.

BORN INTO AN ARMY FAMILY AT SCHOFIELD BARRACKS, HAWAII, HE WAS THE SON OF A MEMBER OF TOM BROKAW’S “GREATEST GENERATION,” WHO STAYED IN AFTER WORLD WAR II ENDED.

ROCKY GRADUATED WITH THE WEST POINT CLASS OF 1959, THEN WENT AIRBORNE AND RANGER. THOSE WHO KNEW HIM ARE NOT SURPRISED BY HIS DETERMINED RESISTANCE AS A POW. THAT QUALITY OF DETERMINATION – – THE WILL TO WIN, TO NEVER QUIT, AND TO PREVAIL NO MATTER THE ODDS – – IS WHAT ENDURES ABOUT ROCKY VERSACE. GENERAL PETE DAWKINS REMEMBERS HIM AS ONE OF THE REGIMENTAL INTRAMURAL WRESTLING CHAMPIONS – – “HE WAS NOT FAST, HE CERTAINLY WAS NOT SKILLED, BUT HE WOULD NEVER GIVE UP.”

HIS SPIRIT AND HIS HEART WERE ALWAYS LARGER THAN HIS OPPOSITION – – HE WAS REGIMENTAL CHAMP IN HIS WEIGHT CLASS THREE YEARS RUNNING. THOSE QUALITIES WOULD SURFACE, ONCE AGAIN, IN THE LAST YEARS OF HIS LIFE. HIS UNSHAKEABLE FAITH IN HIS GOD GAVE HIM GREAT INNER STRENGTH. HAD HE RETURNED, ROCKY VERSACE WOULD PROBABLY BE A PRIEST TODAY IN THE MARYKNOLL ORDER OF MISSIONARIES AND WOULD PROBABLY STILL BE IN COUNTRY, MINISTERING TO THE CHILDREN OF VIETNAM. THAT’S WHERE HE WAS HEADED HAD HE COME OUT AS SCHEDULED. I COULD NOT TELL YOU HOW THE MARYKNOLLS AND THE CHILDREN OF VIETNAM MIGHT BE LIVING LIFE DIFFERENTLY TODAY.

BUT THAT WAS NOT TO BE. HIS CAPTORS, REALIZINGTHAT THEY WERE NOT GOING TO BREAK HIS SPIRIT, NEVER GOING TO TURN HIM THROUGH THEIR PROPAGANDA AND LIES, TOOK OUT THEIR FRUSTRATIONS ON HIM. THEY EXECUTED HIM ON 26 SEPTEMBER 1965. THE LAST TIME THAT HIS FELLOW PRISONERS HEARD FROM HIM, HE WAS SINGING “GOD BLESS AMERICA” AT THE TOP OF HIS VOICE FROM HIS ISOLATION BOX.

PERHAPS THE MOST INSIGHTFUL COMMENTARY ON CAPTAIN ROCKY VERSACE IS PROVIDED BY THEN-SFC DAN PITZER, WHO SERVED WITH HIM IN COMBAT AND IN CAPTIVITY – -“ROCKY WALKED HIS OWN PATH. ALL OF US DID, BUT FOR THAT GUY, DUTY, HONOR, COUNTRY WAS A WAY OF LIFE. HE WAS THE FINEST EXAMPLE OF AN OFFICER I HAVE KNOWN . . . . ONCE, ROCKY TOLD OUR CAPTORS . . . . THEY MIGHT AS WELL KILL HIM THEN AND THERE IF THE PRICE OF HIS LIFE WAS GETTING MORE FROM HIM THAN NAME, RANK, AND SERIAL NUMBER . . . . HE GOT A LOT OF PRESSURE AND TORTURE, BUT HE HELD HIS PATH . . . HE WAS BRUTALLY MURDERED BECAUSE OF IT . . . . I’M SATISFIED HE WOULD HAVE IT NO OTHER WAY. I KNOW THAT HE VALUED THAT ONE MOMENT OF HONOR MORE THAN HE WOULD A LIFETIME OF COMPROMISES.”

TODAY, I AM HUMBLED AND PRIVILEGED TO HONOR THIS MAN AND HIS FAMILY. WE ARE PROUD TO HAVE ALL OF YOU HERE, AND WE ARE GRATEFUL FOR YOUR PATIENCE. TODAY’S CEREMONY HAS ALSO BEEN ABOUT PERSEVERANCE – – ROCKY’S HAS BEEN LOVINGLY MATCHED BY THE PERSEVERANCE OF THOSE GATHERED HERE. IT HAS ALSO BEEN ABOUT JUSTICE. I WANT TO CONGRATULATE THE VERSACE FAMILY ON THE VERY HIGH HONOR THAT THE NATION AND OUR COMMANDER IN CHIEF HAVE PAID TO CAPTAIN ROCKY VERSACE; I WANT TO THANK THE FRIENDS AND CLASSMATES OF ROCKY VERSACE FOR THEIR STEADFASTNESS IN THE FACE OF SUCH A LONG WAIT TO RECOGNIZE THIS SOLDIER OF EXTRAORDINARY STRENGTH, CHARACTER, AND VALOR.

GOD BLESS HIS SOUL, GOD BLESS EACH OF YOU, GOD BLESS OUR GREAT ARMY AND THIS WONDERFUL COUNTRY OF OURS. THANK YOU.

SEC. 541. AUTHORITY FOR AWARD OF THE MEDAL OF HONOR TO HUMBERT R. VERSACE FOR VALOR DURING THE VIETNAM WAR.

(a) WAIVER OF TIME LIMITATIONS- Notwithstanding the time limitations specified in section 3744 of title 10, United States Code, or any other time limitation with respect to the awarding of certain medals to persons who served in the military service, the President may award the Medal of Honor under section 3741 of that title to Humbert R. Versace for the acts of valor referred to in subsection (b).

(b) ACTION DESCRIBED- The acts of valor referred to in subsection (a) are the actions of Humbert R. Versace between October 29, 1963, and September 26, 1965, while interned as a prisoner of war by the Vietnamese Communist National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) in the Republic of Vietnam.

Bush To Award Medal of Honor

January 14, 2002

As America embraces its new heroes from the War on Terrorism, President Bush will soon award what is perhaps the last Vietnam-era Medal of Honor to an Army Ranger and Green Beret intelligence officer who fought, was captured, and resisted compromising the Code of Conduct during nearly two years of torture (63-65) before being executed by his frustrated and bewildered communist Viet Cong captors.

President Bush signed legislation authorizing the Medal of Honor for the late Captain Humbert R. “Rocky” Versace December 28, 2001. Mike Faber, president of the Friends of Rocky Versace, said that he was hopeful that the medal would be posthumously awarded at the White House to Versace’s surviving brother, Steven in a couple of months.

His fellow captive and author of “Five Years to Freedom,” the late Colonel Nick Rowe once admonished: “Remember him. I am going to see that people do because for me he was the greatest example of what an officer should be that I have ever come in contact with.”

Agreeing with Rowe’s assessment, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz recently told the corps of cadets at the United States Military Academy where Rocky was a member of the Class of ’59: “Look to your left – look down the line to your right. You may well be seeing a hero; you may well be looking at another Rocky Versace.”

Versace, one of the first names appearing on the Vietnam War Memorial’s wall in Washington, D.C., shares a special kinship with the Special Forces in Afghanistan. Like them, Rocky was one of the first to fight and was on dangerous ground gathering intelligence when captured after fighting to his last three rounds of ammunition and twice being wounded by fire.

On October 29, 1963, Versace (near the end of a second tour in Vietnam) and two other American advisors accompanied a Vietnamese Civilian Irregular Defense Group company on an operation near Le Couer, Republic of Vietnam, when they were ambushed.

The three Americans were captured during the eight-hour firefight. For almost two years, Rocky Versace suffered in a Viet Cong prison camp, adamantly refusing to accept his captors’ vicious and inhumane attempts at propagandizing and repeatedly trying to escape.

On September 26, 1965, North Vietnam’s “Liberation Radio” announced the execution of Rocky Versace and another American POW ostensibly in retaliation for the deaths of 3 terrorists in Da Nang.

Remains Never Recovered

Versace’s remains have never been recovered. His stone at Arlington National Cemetery stands above an empty grave. The last memory of the remarkable Versace was that of his fellow captives who described the stalwart officer loudly singing “God Bless America,” from his tiger cage the night before his execution.

One of the great ironies of Rocky’s death was that he was just weeks away from leaving the Army and studying for the priesthood. His goal: Returning to Vietnam as a Maryknoll missionary to work with orphaned children.

Retired Lieutenant General Howard G. Crowell, Jr.: “Rocky was indeed obsessed with the idea of duty, honor, country…. No one worked harder or more diligently than he…. He was so eager to accomplish his mission of gathering intelligence that it was bound to get him into danger sooner or later.”

Retired U.S. Army Brigadier General John W. Nicholson: “By spring of 1964 the farmers were talking about one U.S. prisoner in particular. They said he was treated very poorly, led through the area with a rope around his neck, hands tied, bare footed, head swollen and yellow in color (jaundice) and hair white.

“They stated that this prisoner not only resisted the Viet Cong attempts to get him to admit to war crimes and aggression, but would verbally counter their assertions convincingly and in a loud voice so the local villagers could hear.

“The local rice farmers were surprised at his strength of character and his unwavering commitment to God and the United States. The villagers’ descriptions of Versace and his resistance became a topic of conversation we could count on hearing as we periodically operated in these remote areas.

“Villagers described Versace’s deteriorating physical condition and added that the worse he appeared physically, the more he smiled and talked about God and America. Our interpreters told us that Captain Versace impressed the villagers with his faith and inner strength.”

Nick Rowe: “Once, Rocky told our captors that…they might as well kill him then and there — if the price of his life was getting more from him than name, rank, and serial number. I’m satisfied that he would have it no other way. I know that he valued that one moment of honor more than he would have a lifetime of compromises.”

Long Road to Medal

The long road to his country’s highest military honor shortened in April 2000 when the commandant of the Marine Corps, General James L. Jones, in an unprecedented cross-service move appealed to Army Chief of Staff General Eric K. Shinseki to award the Medal to Versace.

On Dec. 20, 2000 then Army Secretary Louis Caldera approved the Medal. On January 12, 2001 former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Henry Shelton signed off on the authorization, sending it to Congress.

The final Medal legislation, SR1438, was appended to the Defense Reauthorization Bill.

The quest for a Medal of Honor for Versace languished until the Friends of Rocky Versace re-ignited the crusade in early 1999.

The Friends also took the lead in collecting funds for the Rocky Versace Plaza and Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial in Alexandria Virginia, a memorial to Rocky and 61 other Alexandrians who died in Vietnam. The memorial is slated for dedication in July 2002.

Honoring the Defiant One

Alexandria Family, Friends Await Executed POW’s Long-Denied Medal

Sunday, May 27, 2001

His head was swollen, his hair completely white and his skin turned yellow from jaundice. He was rail thin, and he had no shoes, and his Viet Cong captors were yanking him around from village to village by the rope tied around his neck.

On patrol in late 1963 in the Mekong Delta, Army Captain Jack Nicholson listened to villagers describe the scene they had witnessed. When they said the American prisoner had continually argued with his captors — using Vietnamese and French to rebut their propaganda — he knew they were talking about Rocky Versace.

“He had a funny expression about him, a smile, a flashing of teeth, that got their attention,” said Nicholson, now a retired Brigadier General living in Virginia. “And then when they heard him speak, they listened, because they couldn’t help it.”

Versace’s defiance grew even as his condition worsened, infuriating his captors. In 1965, at age 27, Versace was executed. His remains have never been recovered. His family was told little. And in the eyes of many, Versace has never received the recognition he earned.

But after a long campaign by supporters, the former Alexandria resident is close to being posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, an award he was denied 30 years ago. An Army recommendation to give the award was approved this year by General Henry H. Shelton, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and forwarded to the secretary of defense’s office.

Unlike the Air Force, Navy and Marines, the Army has never awarded the Medal of Honor to a POW from Vietnam for actions during captivity. Pentagon officials said they think it would be the first time in the modern era that the medal has gone to an Army POW for heroism during captivity.

“It’s well known around here that the Army’s very reluctant to give the award to a prisoner,” said a Pentagon official, who ascribes the Army’s attitude to a stigma associated with being captured.

Today, in conjunction with Memorial Day observances, a band of supporters will be near the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, raising money for a memorial in Alexandria to honor Versace. For those who know it, Versace’s story has made an indelible impression.

“He told them to go to hell in Vietnamese, French and English,” one of Versace’s fellow captives, Dan Pitzer, who died in 1997, told a historian. “He got a lot of pressure and torture, but he held his path. As a West Point grad, it was duty, honor, country. There was no other way. He was brutally murdered because of it.”

Another prisoner held with Versace, James “Nick” Rowe, escaped in 1968 after five years of captivity. Rowe made an impassioned plea to President Richard M. Nixon that Versace receive the Medal of Honor, describing how his resistance deflected punishment from other captives and stiffened their will to resist.

The Army downgraded the award to a Silver Star. Rowe, embittered, kept talking about Versace until the day he died, assassinated by communist rebels in 1989 while serving as a U.S. military adviser to the Philippine armed forces.

The pending honor will focus attention on a group of POWs who have received little recognition. While the ordeals suffered by downed aviators who were imprisoned in North Vietnam, such as Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), are well documented, less has been said about the more than 200 prisoners, mostly infantry soldiers, held in horrendous jungle camps in South Vietnam.

Versace is “a perfect symbol for a lot of the guys in the South who were overlooked,” said Stuart Rochester, a Department of Defense historian and co-author of a history on Vietnam POWs. “The guys in the South really took tougher punishment than the guys in the North.”

The medal will come too late for Versace’s mother, who died in 1999, never fully accepting that her son was gone.

“My mother, she never gave up,” said one of Rocky’s brothers, Dick Versace, president of the National Basketball Association’s Vancouver Grizzlies. “Until she died, she thought he’d come walking out of those jungles any day.”

Humbert Roque “Rocky” Versace was just a few days short of joining a seminary to become a priest when he was captured. His father, Humbert, was a West Point graduate and Army officer, his mother, Tere, an accomplished author who would write “The Fifteenth Pelican,” a short story that became the basis for “The Flying Nun.”

The oldest of five children in a close, strict Catholic household in Alexandria’s Del Ray neighborhood, Rocky took on the role of father when Humbert Versace was away with the Army. He had a firm sense of duty and moral responsibility — in addition to being infuriatingly opinionated and headstrong, his brothers said.

“If he thought he was right, he was a pain in the neck,” said his brother Steve, a professor at the University of Maryland’s University College. “If he knew he was right, he was absolutely atrocious.”

Versace followed his father to West Point, graduating in 1959. Assigned to the “Old Guard” at Fort Myer, he chafed at the ceremonial duties and volunteered for a tour in Vietnam.

In 1962, Vietnam had barely registered on the American consciousness. There were no U.S. combat troops, only a few thousand military advisers sent to help the South Vietnamese government fight a communist insurgency.

Versace was assigned as an intelligence adviser for the South Vietnamese army in the Mekong Delta. Tall, dark-haired and handsome, Versace quickly made his mark. “If you were going to ask for a West Point cadet from central casting, he was it,” said Don Price, a Marine officer who met him there.

Versace immersed himself in Vietnamese culture and the delta town of Camau. He created dispensaries, procured tin sheeting to replace thatch roofs and arranged for tons of bulgur wheat to feed family pigs, Price said. He wrote to schools in the United States and got soccer balls for village playgrounds.

When his one-year tour ended, Versace volunteered for a second stint and then planned to leave the Army. He had been accepted into the Maryknoll Order and wanted to work with children in Vietnam.

In October 1963, two weeks before his second tour was to end, Versace accompanied an operation near U Minh Forest, a Viet Cong stronghold. The South Vietnamese company was overrun by a large enemy force, and Versace went down with three rounds in the leg. He, Rowe and Pitzer were taken prisoner, stripped of their boots and led into the forest.

It was a dark maze of mangrove, canals and swamps. The prisoners were kept in bamboo cages, deprived of food and exposed to insects, heat and disease.

Versace’s untreated leg became badly infected, but within three weeks he tried to escape, dragging himself on his hands and knees. Guards soon discovered him crawling in the swamp. Back in camp, they twisted his injured leg.

Versace was kept in irons, flat on his back and frequently gagged in a dark and hot bamboo isolation cage that was 6 feet long, 2 feet wide and 3 feet high.

The VC cadre set up indoctrination classes, but Versace attended only at the tip of a bayonet. Rowe and Pitzer “adopted a sit-and-listen attitude between bouts of body-wrenching dysentery, feeling the more we said, the worse off we’d be,” Rowe later wrote. “Rocky, on the other hand, was engaging all comers.” The instructor’s voice would “climb an octave from its already high pitch” as Versace tripped him up with verbal gymnastics, Rowe said.

Increasingly, Versace was separated from the other prisoners.

Patrolling the delta, Nicholson kept hearing stories from admiring rice farmers about the resolute, white-haired POW whom the Viet Cong pulled around by a rope.

“Rocky Versace made an impression on these people, which heightened our eagerness to rescue him and caused us to immediately respond to any intelligence we could get,” said Nicholson, who now works for a veterans organization in Alexandria.

Three times, after receiving tips about Versace’s whereabouts, U.S. advisers launched helicopters to rescue him, and three times they came back empty-handed, taking heavy casualties on one occasion.

“It was very frustrating,” Nicholson said. “Very frustrating and very sad.”

When his tour ended in 1964, Nicholson went home and called Versace’s father, who wept at the news of the attempted rescues. “You know, it’s been almost a year since he was captured, and I haven’t heard one word, not one word, from the government,” Humbert Versace told him, Nicholson said.

Back in Vietnam, Versace tried three more times to escape, and his treatment worsened. The last the other prisoners heard from him, he was singing “God Bless America” at the top of his lungs from his isolation box.

On September 29, 1965, Hanoi Radio announced that Versace had been executed in retaliation for the killing of suspected communist sympathizers by South Vietnam.

His family learned the news from television reports. “The thing that hit my dad hardest was when he heard Rocky had been executed on the 6 o’clock news,” said Steve Versace. “I think he started dying then.”

Tere Versace refused to believe it, pressing for more information and flying to Paris to try to meet with North Vietnamese diplomats.

But for most people, the story told by Rowe after he escaped ended any hope Versace might be alive. At a private meeting at the White House in 1969, Nixon was one of the first to hear it.

“The president wasn’t prepared — I don’t think anyone was — for what we were about to hear,” said retired Colonel Ray Nutter, an Army congressional liaison officer who accompanied Rowe to the meeting.

Rowe spoke for more than an hour, describing the prisoners’ treatment and Versace’s resistance. When it ended, Nixon, visibly moved, stood and hugged Rowe, Nutter said. Rowe told the president that Versace deserved the Medal of Honor. Nixon turned and told the liaison officers to “make damn sure” it happened, Nutter said.

The submission sat for two years before being turned down in 1971.

“The political climate of the time stopped that thing right in its tracks,” Nutter said, noting that Rowe had publicly criticized antiwar senators.

Versace’s case has been pushed in recent years by a hodgepodge group of soldiers and civilians who have heard his story: officers in the Army Special Forces command, West Point classmates and friends from Alexandria.

What they have in common is the haunting image of a man who, as Rowe wrote, did not break, or even bend. Said Nicholson, “It makes you think, ‘Good Lord, could I be that strong?’ ”

RANGER HALL OF FAME NOMINATION CAPTAIN HUMBERT R. VERSACE

TAB A: Nomination Cover Letter

INTRODUCTION

A. Purpose of Letter

Captain Humbert R. Versace, Armor, is hereby nominated for induction into the US Army Ranger Hall of Fame. Captain Versace distinguished himself by conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while a prisoner of war. Captain Versace’s rigid adherence to the Ranger Creed and the Code of Conduct, and his total refusal to acquiesce to his captors demands, resulted in him being summarily executed by his Viet Cong captors on or about 26 September 1965.

B. Career Summary

Captain Versace graduated from the US Military Academy in 1959 and was commissioned in the Armor. He was a member of Ranger Class 60-4 and was awarded the Ranger Tab. Prior to his 1962 assignment to Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam, he served with 3/40 Armor and the 3d Infantry(Old Guard)

II BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF CAPTURE

A. Circumstances

In October, 1963, Captain Humbert Rocque (Rocky) Versace was a U.S. Army MAAG intelligence advisor assigned to support Province forces (Civil Guard and Self Defense Forces) operating in An Xuyen Province(IV Corps Tactical Zone) in the Mekong Delta Region of South Vietnam. On 29 October, Captain Versace made a liaison visit to the Special Forces Team A-23 camp at Tan Phu to exchange intelligence reports on enemy activities in the area. A determination was made to launch an attack against VC forces in the area. Captain Versace accompanied the attacking CIDG force with Special Forces Team members First Lieutenant Nick Rowe and Sergeant First Class Dan Pitzer. Captain Versace was seriously

wounded by three BAR rounds to his leg while helping to cover the withdrawal of CIDG forces in the face of a determined and very heavy Viet Cong Main Force attack. At that point CaptainVersace, Lieutenant Nick Rowe and Sergeant Pitzer as well as the CIDG forces, were almost out of ammunition. Captain Versace had 7 rounds left in his carbine and was about to charge the Viet Cong in one last valiant

effort to stop their pursuitt when he was wounded. Row and Pitzer were also wounded and all three captured by the Viet Cong.

After being stripped of their boots, weapons, and personal possessions, Captain Versace, Lieutenant Rowe, and Sergeant Pitzer were bound and led barefoot into jungle captivity by their Viet Cong captors, somewhere in the vast darkness of the U Minh Forest. Captain Versace had his eye glasses removed, leaving him virtually blind since his vision was very poor without them.

III SUMMARY OF ACTIONS IN POW CAMPS

Upon arrival on the VC jungle prison camp, Captain Versace assumed command as senior prisoner to represent his fellow Americans, and immediately was labeled as a trouble maker by his captors for insisting that the VC honor the Geneva Convention’s protections for captured POWs. The Viet Cong didn’t acknowledge any protections guaranteed to POWs as required by the Geneva Convention, and

considered the three Americans to be “war criminals.” Soon Captain Versace was separated from Rowe and Pitzer and put in a bamboo isolation cage six feet long, two feet wide, and three feet high. According to Rowe and Pitzer “He was kept in irons, flat on his back, it was dark and hot [from thatch on the roof and outside bamboo walls], and they only let him out to use that latrine and to eat. What they were trying to do was to break him. They even offered better food and they would let him out if he would cooperate, but he would not. They wanted to get him to (1) quit arguing with them (2) and accept their propaganda. The Vietnamese gave him the word that they knew he was an S-2 Advisor.”

IV SPECIFIC ACTIONS

A. Organizing/Encouraging other POWs

Though suffering from a badly wounded and infected leg wound, Captain Versace assumed the position of Senior American Prisoner and demanded that the Viet Cong treat the American prisoners according to the protections of the Geneva Convention. He protested vehemently when the VC cadre refused to recognize them as “prisoners of war,” but treated them instead as “war criminals,” subject to the whims of individual cadre to decide matters of life or death. For his vociferous protestations against starvation rations, lack of adequate medical treatment for their wounds suffered when captured, deliberate withholding of medicines to treat life threatening diseases, and the overall sub-human living conditions in a brutal jungle environment, Captain Versace was soon ordered to be kept in an isolation hut with thatch on the roof and sides, which made mid-day temperatures inside as hot as an oven. The DOD Prisoner and Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) states that: “. . . CaptainVersace demonstrated exceptional leadership by communicating positively to his fellow prisoners. He lifted morale when he passed messages by singing them into the popular songs of the day. When he used his Vietnamese language skills to protest improper treatment to the guards, Captain Versace was again put into leg irons and gagged. Unyielding, he steadfastly continued to berate the guards for their inhuman treatment. The communist guards simply elected harsher treatment by placing him in an isolation box, to put him out of earshot and to keep him away from the other US POWs for the remainder of his stay in camp. However Captain Versace continued to leave notes in the latrine for his fellow inmates, and continued to sing even louder.” Captain Versace wouldn’t give his captors any information other than the big four of name, rank, service number, and date of birth, as required by the Geneva Convention and the U.S. Code of Conduct.

B. Active Resistance

According to Sergeant Pitzer “Rocky walked his own path. All of us did but for that guy, duty, honor, country was a way of life. He was the finest example of an officer I have known. To him it was a matter of liberty or death, the big four and nothing more. There was no other way for him. Once, Rocky told our captors that as long as he was true to God and true to himself, what was waiting for him after this life was far better than anything that could happen now. So he told them that they might as well kill him then and there if the price of his life was getting more from him than name, rank, and serial number.” Sergeant Pitzer also noted that the VC realized Rocky was a captain, Nick[Rowe} a Lieutenant, and I a Sergeant, so they singled him out as ranking man. Rocky stood toe to toe with them. He told them to go to hell in Vietnamese, French, and English. He got a lot of pressure and torture, but he held his path. As a West Point grad, it was Duty, Honor, Country. There was no other way. He was brutally murdered because of it…I’m satisfied that he would have it no other way. I know that he valued that one moment of honor more than he would have a lifetime of compromises.”

C. Escape Attempts

DPMO records reveal that: “Still suffering from debilitating injuries in the prison camp dispensary three weeks later, Captain Versace took advantage of the first opportunity to escape when he attempted to drag himself on his hands and knees out of the camp through dense swamp and forbidding vegetation to freedom. Crawling at a very slow pace, the guards quickly discovered him outside the camp and recaptured him. After recapture Captain Versace was returned to leg irons and his wounds were left untreated. He was placed on a starvation diet of rice and salt. During this time period Viet Cong guards told other U.S. POWs in the camp that despite beatings, CPT Versace refused to give in. On one occasion a guard attempted to coerce him to cooperate by twisting the wounded and infected leg, to no avail. They described Versace as an uncooperative’ prisoner.”

D. Rejection of Brain Washing

In February, 1964 the VC cadre forced the American prisoners to attend a political school, which was a combination of 2,000 years of Vietnamese history of repelling foreign invaders from the Chinese all the way to the Americans and their Saigon “puppet” government, and intense political indoctrination from the VC perspective. The VC concept was to repeat the same themes over and over, so that after months of hearing the same lessons, prisoners would become “re-educated” to accept the communist view of their inevitable victory over the Americans and the Saigon government, no matter how long it took to achieve, or the cost in VC and NVA casualties. Rowe recalled that it took two guards to force Captain Versace to attend, since he would not go on his own. “. . . I remember Rocky saying you can make me come to this class, but I am an officer in the United States Army. You can make me listen, you can force me to sit here, but I don’t believe a word of what you are saying.”

E. Focusing VC wrath on himself rather than Rowe and Pitzer

Captain Versace willingly sacrificed his life by focusing all of the anger of the VC cadre on him, instead of Lieutenant Rowe and Sergeant Pitzer, so that they might have a better chance to survive. By constantly arguing loudly with his communist cadre in English, Vietnamese, and French, he caused them considerable

consternation during a “political school” that was supposed to get the Americans to write statements disloyal to the U.S. government and their South Vietnamese allies. Instead, they got nothing but very loud arguments as Captain Versace was able to take on three indoctrinators easily in three languages.

F. Inspiring local villagers

Captain Versace and the other US Army prisoners were frequently moved from one POW camp to another. In the case of Versace he was often moved individually without benefit of being near his fellow prisoners. BG(R) John Nicholson participated in the numerous operations launched to free Captain Versace and his fellow prisoners. According to BG Nicholson and others, villagers reported that Captain Versace was paraded through the hamlets with a rope around his neck, hands tied, bare footed, head swollen and yellow in color, with hair turned white. The villagers stated that Captain Versace not only resisted the Viet Cong attempts to get him to admit war crimes and aggression, but would verbally and convincingly counter the VC assertions in a loud voice so that the villagers could hear. The local rice

farmers were surprised at Captain Versace’s strength of character and his unwavering commitment to his God and the United States.

VI ADHERENCE TO HIGHEST STANDARDS

A. Code of Conduct

Captain Versace’s tenacious and heroic adherence to the Code of Conduct was in keeping with the absolutely highest standards of the United States Army and centuries of Ranger tradition. At no point from capture to execution, despite torture and isolation, did Captain Versace provide his captors with any information other than name, rank. Serial number and date of birth.

B. Ranger Creed

Although the Ranger Creed was not a formalized document when Captain Versace was captured, he lived, and died, by its tenets:

1. Never Shall I Fail My Comrades

Captain Versace fought to protect his comrades until seriously wounded by BAR fire. He was about to literally sacrifice himself by attacking the Viet Cong with his remaining seven carbine rounds when wounded. In captivity he was willing to accept death rather than compromise the Ranger Creed, Code of Conduct , and the ideals of Duty, Honor, and Country. As senior American POW, Captain Versace deliberately forced his captors to focus their harsh treatment on him rather that the other American prisoners. His Ranger training, his unshakable belief in God and Country, sustained him throughout his captivity until his death.

2. Under No Circumstances Will I Embarrass My Country

Captain Versace resisted all attempts by his captors to force him to embarrass his country, despite torture, deprivation of medical treatment and food and isolation. Captain Versace’s active and visible resistance to his captors as he was paraded through the hamlets, impressed the villagers rather than proving the VC point that Americans were not invincible. Villagers added that the worse he appeared physically, the more he smiled and talked about God and America. The last time that any of his fellow prisoners heard from him, Captain Versace was singing “God Bless America” at the top of his voice from his isolation box. On 29 September 1965 the National Liberation Front announced that they had executed Captain Versace, reportedly in reprisal for actions of the South Vietnamese Government.

3. Surrender is not a Ranger Word

According to a Viet Cong cadre in the POW camp, Captain Versace tried to escape four times. The first attempt took place when he was still in the camp dispensary recovering from his three leg wounds. He was barefoot. Captain Versace was also virtually blind when he made these attempts. After each attempt, Captain Versace was beaten and had his feet manacled. His rice ration was also cut. As then Major Nick Rowe said later about Captain Versace, “He could have bent, he could have broken, he could have lived. But he chose not to..” Instead Captain Versace lived and died by the Ranger Creed.

C. Medal of Honor Nomination

President Nixon verbally directed then Major Nick Rowe to submit the necessary documents to support award of the Medal of Honor to Captain Versace for his heroism before and during captivity. On 17 November 1969 (then) Major Rowe submitted a recommendation for posthumous award of the Medal of Honor to Captain Versace. For a number of unexplained reasons related to bureaucratic

concerns rather than the nature of Captain Versace’s heroism, Department of the Army on 19 May 1971, downgraded the award to the a posthumous Silver Star. US Army Special Forces Command is currently preparing and resubmitting the nomination for the Medal of Honor.

VI SUMMARY

Captain Versace’s induction into the US Army Ranger Hall of Fame is certainly warranted by his heroism and total commitment to the bed rock values which Rangers hold dear even at the cost of his life.

Biography

US ARMY RANGER HALL OF FAME NOMINATION

CAPTAIN HUMBERT R. VERSACE

TAB B: Ranger Career Summary

Captain Humbert Rocque Versace graduated from the US Military Academy in 1959 and was commissioned in the Armor. He was a member of Ranger Class 4-60 and was awarded the Ranger Tab on 18 December 1959 (Special Orders # 268, USAIC, 18 Dec 59). Upon graduation from Ranger School, Captain Versace attended Airborne School and was awarded the parachutist badge (US Army Infantry Center Special Orders # 27 Parachutist Badge 5 February 60). He then served with 3/40 Armor, 1st Cavalry Division, Korea, as a medium tank platoon leader from March 1960 to April 1961. Captain Versace was then assigned to the 3d Infantry(Old Guard), where he served as a tank platoon leader in Headquarters and Headquarters Company. After volunteering for duty in RVN, he attended (January through April 1962) the Military Assistance Institute, the Intelligence course at Fort Holabird and the USACS Vietnamese language Course. On 12 May 62 Versace was Assigned as Intelligence Advisor, Long Kanh, Province, III Corps ( Xuan Loc). On 4 November 62, Versace was reassigned as Assistant G2 Advisor, Staff Advisory Branch, 5th IN Division, III Corps (Location Bien Hoa). Following the completion of his initial 12 month tour, Captain Versace extended his tour for an additional six months, and was assigned to Advisory Team 70, as Intelligence Advisor to Civil Defense and Self Defense Forces operating in An Xuyen Province(IV Corps Tactical Zone) in the Mekong Delta Region of South Vietnam. It was while in this assignment that Captain Versace was wounded and captured on 29 October, 1962 while on an operation with Special Forces Team A-23, at Tan Phu, on the edge of the U Minh Forest.

Captain Versace was a prisoner of the Viet Cong until 26 September 1965, when he was executed by his captors because of his tenacious resistance and rigid adherence to the Code of Conduct and the Ranger Creed.

Captain Versace was awarded a posthumous Purple Heart on 2 July 1966 and a posthumous Silver Star on 19 May 1971. His nomination for the Congressional Medal of Honor was lost or misfiled. US Army Special Operations Command is resubmitting the Medal of Honor nomination. Captain Versace was awarded the Combat Infantry Badge during his first tour as an Advisor in Vietnam. He was

awarded the Expert Infantryman’s Badge while assigned to The Old Guard (Special Orders # 131, Headquarters 3rd Infantry, 5 July 61). Captain Versace was also posthumously awarded the POW medal on 10 November 1999 and Special Forces Tab on 12 July 1999.

Awards and Decorations

US ARMY RANGER HALL OF FAME NOMINATION

CAPTAIN HUMBERT R. VERSACE

TAB G: Assignments, Awards and Decorations

Assignments

1 July 1955-3 June 1959: Cadet, USCC, US Military Academy

3 June 1959: Commissioned Second Lieutenant, Armor

11 August -21 October 1959: Armor Officer Basic Course 2B

23 October-18 December 1959: US Army Ranger School, Class 4-60

22 March 1960 – 11 April 1961: 3rd Battalion, 40th Armor, Medium Tank

Platoon Leader, Korea,

16 May 1961- 31 December 1962: HQ 3rd Infantry, Tank Platoon Leader, Ft. Myer, VA, First Lieutenant

2 January – 26 January 1962: Military Assistance Institute, Arlington, Virginia

4 February to 5 March 1962: Intelligence Course, US Army Intelligence Center, Fort Holabird, Maryland

30 March – 1 May 1962: USACS Presidio Language School, Monterey, California

12 May – 3 November 1962: Intelligence Advisor, Long Khanh Province, III Corps, Xuan Loc, RVN

4 November 1962- May 1963: Assistant G-2 Advisor, Staff Advisory Branch, 5th Infantry Division, III Corps, Bien Hoa

June 1962 – October 1963: Advisory Team 70, Intelligence Advisor, An Xuyen, IV Corps Tactical Zone, Captain

29 October 1963- 26 September 1965: Prisoner of War

Awards and Decorations

Ranger TAB, Special Orders # 268, HQ US Army Infantry Center, 18 December 1959

Parachutist Badge, Special Orders # 27, HQ US Army Infantry Center, 5 February 1960

Expert Infantry Badge, Special Orders # 131, HQ 3rd Infantry, 5 July 1961

Combat Infantry Badge, October 1962 (exact date, orders number Unk)

Special Forces Tab (Posthumous), 12 July 1999

Silver Star (Posthumous), 19 May 1971

Purple Heart (Posthumous), 2 July 1966

POW Medal (Posthumous), 10 November 1999

Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal

VERSACE, HUMBERT ROQUE

CPT US ARMY

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 07/01/1960 – 07/01/1966

- DATE OF BIRTH: 07/02/1937

- DATE OF DEATH: 07/01/1966

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 07/01/1966

- BURIED AT: SECTION MG SITE 108

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard