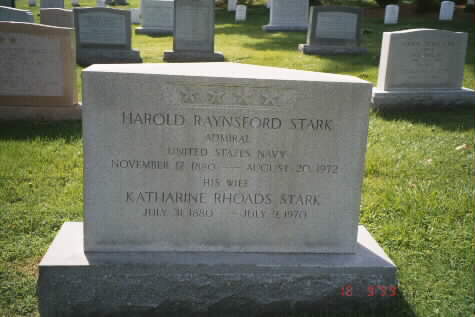

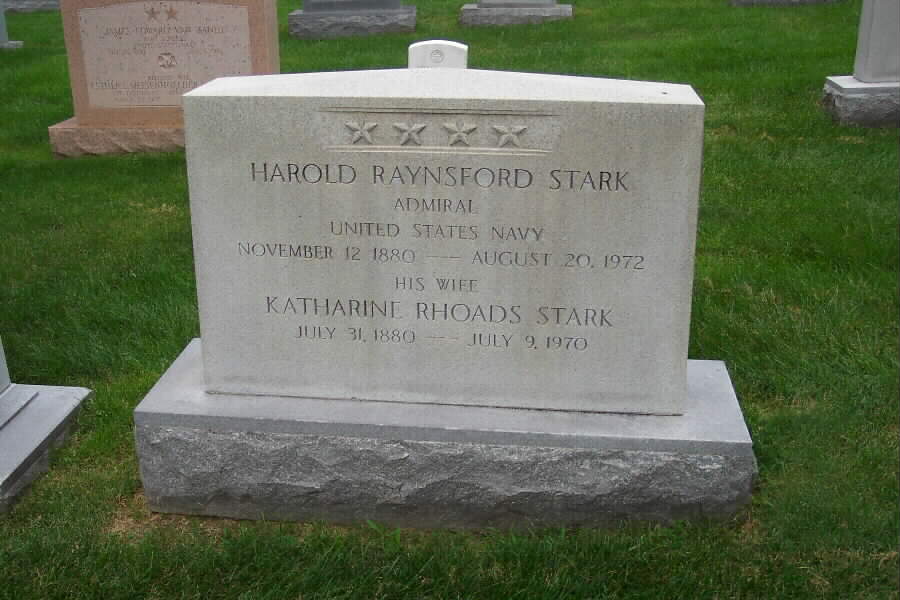

Born at Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, November 12, 1880, Harold Raynsford Stark graduted from the United States Naval Academy in 1903. He married Katherine Adele Rhodes, July 24, 1907.

He was commissioned an Ensign, February 2, 1905, and advanced through the grades to Admiral, August 1, 1939. He served in various assignments at sea and ashore and in 1917, following U.S. entry into World War I, commanded the transfer of a torpedo flotilla from a station in the Philippines to the Meriterranean. He was an Aide to Admiral William S. Sums, 1917-19.

After the war, he served on the USS South Dakota and the USS West Virginia and in 1924-25 commanded the USS Nitro. In 1925-28 he was Inspector in Charge of Ordnance at the Naval Proving Grounds, Dahlgreen, Virginia. From 1928 to 1930 he was on the staff of the Commander of Destroyer Squadrons, Battle Fleet, ultimately becoming Chief of Staff and from 1930 to 1933 was an Aide to the Secretary of the Navy. He again commanded the USS West Virginia in 1933-34 and, promoted to Rear Admiral in November 1934, was Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance from 1934 to 1937. In September 1937 he was given command of Cruiser Division 3, Battle Force, and in July 1938 moved up to command of all Crusier Divisions, Battle Force, with the rank of Vice Admiral.

In August 1939 he became Chief of Naval Operations with the rank of Admiral, having been selected by President Franklin D. Roosevelt over more than 50 more senior officers. He held that post until March 1942 when, in the reorganization that followed the Pearl Harbor disaster, he was replaced by Admiral Ernest J. King. Given largely administrative duties as Commander of U.S. Forces in Europe, a post he retained until August 1945. He retired from the Navy in April 1946. He suffered severe criticism for his alleged failure to forward key intelligence information to Admiral Kimmell at Pearl Harbor before the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941, and was cesured in a Naval investigation in 1945. That judgement was mitigated in later years.

He died at Washington, D. C. on August 20, 1972 and was buried in Section 30 of Arlington National Cemetery. His wife, Katherine Adele Rhoads Stark (July 31, 1880 – July 9, 1970), is buried with him.

BY WILLIAM C. KASHATUS

Times-Shamrock Correspondent

Courtesy of the Wyoming County (Pennsylvania) Press Examiner

16 June 2009

At 1:47 p.m., on the sleepy Sunday afternoon of December 7, 1941, a Japanese dive-bomber, first of a wave of 183 carrier-based planes, swept low over Pearl harbor, America’s chief Pacific base.

Flying to within 50 feet of the ground, the blazing suns clearly visible on their wings, dive bombers wreaked havoc on the local airfields. In a few minutes the Japanese virtually destroyed U.S. air power in Hawaii.

At the same time, bombers came storming in over the American fleet tied up along Battleship Row. An armor-piercing bomb crashed through to the second deck of the battleship Arizona and triggered an explosion. The Arizona gave a tremendous leap, then cracked in two as it settled to the bottom. Another battleship, the West Virginia, afire amidships, sank.

Yet another; the Oklahoma, struck by five torpedoes, rolled over in the shallow water and lay with her bottom pointed grotesquely toward the sky. That afternoon, amidst the stench of burning oil, the roar of flames and the cries of the trapped and wounded, the Navy began to count its losses.

The surprise attack had sunk or badly damaged 18 ships, destroyed 188 planes and damaged 159 more. More than 2,400 Americans were killed, nearly half in the explosion of the Arizona, and 1,178 were wounded. The damage would have been even worse had the Japanese targeted Pearl Harbor’s invaluable oil facilities.

The next day a grim President Franklin D. Roosevelt went before Congress. “December 7,” he began “is a day that will live in infamy” as the Japanese launched an “unprovoked and dastardly attack” on American soil.

Roosevelt asked Congress for a declaration of war and received it, almost unanimously. Three days later Germany and Italy announced that they, too, were at war with the United States.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor remains of the greatest historical controversies. Questions still exist over what, if any, advance knowledge the United States officials had of the attack. Some historians believe that Roosevelt knew about Japan’s plans and allowed the attack. It was the only way he could persuade an isolationist Congress and public to enter a war in support of longtime allies, Britain and France.

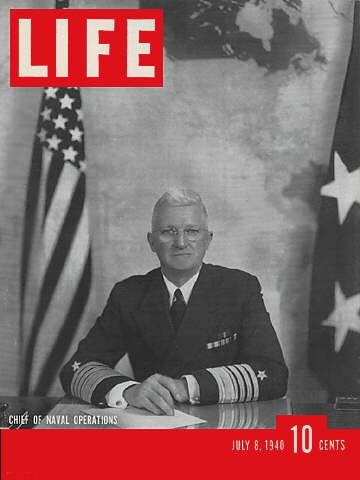

One of the individuals who took the blame for Pearl Harbor was Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Harold Stark. Stark, a Wlkes-Barre native, was heavily involved in planning the United States’ pre-war strategy. His personal relationship with Roosevelt and failure to provide sufficient warning led many to blame him for the success of the attack. But a closer examination of the attack reveals that Stark was made a scapegoat for U.S. unpreparedness.

Harold Rainsford Stark was born in Wilkes-Barre on November 12, 1880. His parents sent him to the Harry Hillman Academy, a military grade school, where the youngster dreamed of wartime heroics. Appointed to the U.S. Naval Academy in 1899, Stark was intelligent, personable and disciplined, and quickly made a favorable impression on his peers. After graduation in 1903, Stark went on to serve on the battleship Minnesota during the Atlantic fleet’s epic cruise around the world between 1907 and 1909.

Stark’s intelligence and self-assuredness gained the lifelong friendship of future president Roosevelt. The two men first met in 1914 when the young navy lieutenant was charged with the task of escorting then assistant secretary of the Navy Roosevelt to his summer home onboard the USS Patterson.

During the navigation of difficult waters, Roosevelt asked Stark to command the ship. “No, sir,” replied Stark gruffly. “This is my command and I doubt your ability to relieve me.” He then increased the ship’s speed and easily navigated the treacherous waters. Thoroughly impressed by the young officer’s ability and confidence, Roosevelt befriended him during World War I. Stark gained extensive experience onboard torpedo boats and in dealing with anti-submarine warfare.

Between 1928 and 1933, the rose rapidly through the ranks serving at various times as commanding officer of the battleships North Dakota and West Virginia, as chief of staff to the commander of the Destroyer Squadrons Battle Fleet, and aide to the Secretary of the Navy.

In 1939, Roosevelt appointed Stark, then a vice admiral, chief of naval operations. He was promoted over 50 senior flag officers for the position. It was an unprecedented decision. As CNO, Stark supervised the expansion of the Navy during 1940 and 1941, constructing a naval force worthy of fighting the Axis powers.

Having close ties to Great Britain’s high command, Stark understood that the British were slowly being pushed back by Nazi Germany. As the main force against the Aix, is Britain were to fall, the U.S. would not likely win a struggle alone. With war looming Stark requested a 40 percent increase in naval forces.

“Dollars cannot buy yesterday,” he said in his appeal on Capitol Hill, insisting that precious time had already been lost in preparing for the nation’s defense. But Congress only granted an 11 percent increase, which was signed into law on June 14, 1940. Two days later, after the fall of Paris to Nazi forces, Congress reconsidered Stark’s plea. Returning to Capitol Hill, Stark introduced what became known as his “two-ocean Navy” bill. The measure called for a 60 percent increase in naval forces and reserved the ability to relocate 30 percent of the funding throughout the war. This would allow the CNO and the president to change the amount of production of certain naval assets as demanded by the war. This time, Congress passed the bill quickly and it was signed into law on July 19, 1940.

Stark’s “two-ocean Navy” became the foundation of naval forces throughout World War II. Without such a vast and immediate buildup of naval force, it is unlikely that Allied forces would have been able to sustain the huge losses to German submarine attacks.

Unfortunately, Stark’s service as CNO was also tainted with controversy. Historians have charged Stark with timidity in dealing with the growing Japanese menace in the fall of 1941. Instead, he encouraged Roosevelt to focus on the war in Europe. In a November 12, 1941, memorandum, the admiral outlined a pre-war strategy that made the protection of Great Britain by defeating Nazi Germany the first priority. Accordi8ng to the plan, the U.S. would maintain forces in the Pacific to fight the Japanese, but no major offensive actions would be initiated. Although this was a radical change from the previous strategy – which made Japan the top priority – Roosevelt and the other Allied leaders agreed that it was the best option for U.S. and world success.

At the same time, Stark strongly advised the president to take all steps necessary to avoid conflict with Japan. Most importantly, the admiral insisted that Roosevelt not sanction an oil embargo against that country. Japan had a large navy, which required excessive oil, yet they had few resources available.

Stark knew an embargo would likely push the country to desperation and war with the oil-rich United States would be unavoidable. His assumption proved correct when the president rejected his advice.

But Stark also realized that the more pressing problem involved Nazi Germany, whose submarines had already been engaged in a series of incidents against U.S. ships. With the admiral’s encouragement FDR declared an unlimited national emergency, demanded that Germany close its U.S. consulate and ordered American ships to shoot on sight any Nazi vessel. When Congress authorized the merchant marine to sail fully armed and to convey Lend-Lease supplies directly to Britain, a formal declaration of war was only a matter of time. Thus, Stark’s strategy was not a matter of “timidity in dealing with Japan,” but rather a practical diplomatic solution to a more pressing threat by the Germans.

Historians also fault Stark for failing to provide sufficient information about an impending Japanese attack on Adm. Husband Kimmel, commander of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor.

During the fall of 1941, as relations between the U.S. and Japan deteriorated, the U.S. Navy began receiving countless intelligence reports of an impending Japanese attack. But so many different locations were identified that it was too difficult to pinpoint an exact location.

Fearing an attack, Stark, in late November, issued a war warning to his commanders across the Pacific stating, “an aggressive move by Japan is expected within the next few days.” He stated that the “number and equipment of Japanese troops and the organization of naval forces indicates an amphibious expedition against either the Philippines, Thai or Kra Peninsula or possibly Borneo.” The warning concluded with an order to “execute appropriate defensive deployment preparatory to carrying out the tasks assigned to WPL 46,” or the emergency actions each base was to take in case of attack. According to the historians, Stark’s warning lacked certainty and urgency, and his lack of planning caught the forces at Pearl Harbor totally unprepared, causing massive casualties. Such criticism, however; fails to acknowledge the fact that Stark’s options were extremely limited. With a constant barrage of information, no official break in negotiations with Japan, and the high unlikelihood of an attack on Pearl Harbor, Stark was trying to prepare every base for the worst. Nor did Admiral Kimmel fully carry out “WPL 46,” at Pearl Harbor. If he had, army and naval forces would have been dispersed throughout the Pacific and the base would have been prepared for a bombing. Considering the circumstances, Stark took every precaution at his disposal to prevent such an attack.

Although Stark’s name would officially be cleared of any charges after an investigation of the Pearl Harbor attack, his name and career were severely blemished. No doubt, Stark was able to continue his career because of Roosevelt’s quick reorganization of Navy administration after Pearl Harbor. The chief of naval operations position was divided between Stark and Admiral Kimmel, who was given primary authority for all operational procedures. In doing so, Roosevelt salvaged both his friend’s and top military adviser’s career.

Stark, realizing the inefficiency of two author figures in one role, conceded his position fully to King in March 1942. The following month, he accepted another appointment in England to become commander; U.S. Forces in Europe. The new post suited Stark better than that of CNO. He had extensive experience in dealing with the Royal Navy, and his new role exploited the skills he had learned from those experiences. Stark directed U.S. Naval operations and training activities on the European side of the Atlantic. In October 1943, he received the additional title of commander; Twelfth fleet.

But Stark’s greatest war time achievement came in June 1944 when he supervised U.S. Navy participation in the D-Day invasion of Normandy. As the largest amphibious attack the world would ever witness, this was no trivial task. Stark’s brilliant effort in preparation for the invasion proved that he had worked hard to recover from whatever mistakes he might have made at Pearl Harbor. Stark, who earned three Navy and one Army Distinguished Service medals, retired from active duty in 1946, but served as a naval adviser in Washington, D.C.

He also maintained a summer residence on the west shore of Lake Carey in Tunkhannock and often flew there by naval sea-plane to spend his weekends. He died on Aug. 21, 1972, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. The U.S. Navy formally recognized Adm. Harold R. Stark’s illustrious 40-year military career on Oct. 23, 1982, when the USS Stark (FFG 31) was commissioned in his name. It was a deserving honor for a genuine hero of World War II.

STARK, HAROLD RAYNSFORD

ADM USN

- DATE OF BIRTH: 11/12/1880

- DATE OF DEATH: 08/20/1972

- BURIED AT: SECTION 30 SITE 433 LH

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard